Trump’s image in a political cartoon: analysis of expressive potential

Abstract

This study is an attempt to describe the expressive means used in American political cartoons covering the most prominent events before and during Donald Trump’s presidency. Political cartoon as a type of political text is widely adopted in political communication with the aim to manipulate people’s minds. The results of the study show the functioning of verbal units at all language levels and nonverbal means (visual metaphors and symbols) that help cartoonists show the Trump’s presidency in a humorous way and shape public opinion about the 45th president of the United States. The graphical means comprising capitalization, font and red colour captivate the reader’s attention by emphasizing the key issues in the cartoons. Phonetic means which are sound effects and sound repetitions stress Trump’s emotional condition, underlying his immediate reactions to any criticism. The lexical means such as comparison and antithesis draw the parallel between Trump and other political actors stating Trump’s role in American politics as a leader. Syntactic techniques (exclamatory, interrogative, and rhetorical sentences) point at Trump’s problem solving skills, and his original ideas. Symbols, hidden in the cartoons, contain extra linguistic information that is necessary for understanding the cartoonist’s message. Visual metaphors transmit the information through easily recognized vivid images and comparisons.

Keywords: Political cartoon, Political discourse, Donald Trump, Political communication, Critical discourse analysis

Introduction

Today one of the most crucial issues for international society is the political situation in the world. The current events perturbate public opinion, the most striking of them evoke wide public resonance. Mass and social media are constantly discussing public figures including political leaders and other politicians. Politics and media have always been interinfluential with the media shaping public opinion and political reality. They [the media] cover political life of the world community, produce and disseminate the political content (Zhikhareva, 2021: 32). The interactive process of transmitting information to the public defines the role of political communication. Political communication plays an increasingly important part in the modern world conveying information on policy trends and political leaders’ views to ordinary citizens. “One of the major functions of political communication is to regulate human behavior, the influence of partners on each other to achieve the planned results” (Karnyushina, Makhina, 2017: 98). Such texts, containing political information, belong to political discourse. The variety of genres in the political discourse speaks of the interest to the political language.

Political discourse is the sphere where the language of politics is used. Much has been said about political discourse in the works of Fairclough (2001), Wodak (2006), van Dijk (2008), Dunmire (2012), Randour, Perrez, Reuchamps (2020), and many others. The methods to the analysis of political discourse are different. “Discourse, in particular political and policy discourse, plays a significant role in creating and disseminating projections of the future” (Dunmire, 2019: 7). E. I. Sheygal (2000), in her turn, considers that the internal part of political discourse is struggle for power. A. Gabets and A. Gene write: ‘Political discourse is therefore usually specified in terms of such issues as manipulation, power and control’ (Gabets, Gene, 2016: 23).

In their systematic review, Randour, Perrez, Reuchamps outlined that ‘political discourse is generally limited to the discourses of (institutionalized) political elites and most specifically to oral monological speeches’ (Randour, Perrez, Reuchamps, 2020: 428). Thus, discourse should be analysed beyond the text itself. It comprises social context of communication, with its participants, speech production and perception bearing in mind background knowledge. We could conclude that discourse is a text with a situational context that gives various conditions for its realization.

Political discourse produces a huge number of texts with verbal and visual components informing readers about political events and opinions, and at the same time having an emotional impact on the reader. One of them is a political cartoon. Today political cartoons have proven to be an influential tool that attracts viewers from all over the world. They present short, humorous, eloquent shots from the world of politics and other spheres of life.

Main part

The purpose of the paper is to point out the key expressive means (verbal and non-verbal (visual)) of political cartoons having Donald Trump as a main character. The current research aims to analyze the expressive means in the cartoon texts on each language level in order to show the most bright and recurrent means and their role in creating Donald Trump’s image. Many research works are devoted to the evaluation of Donald Trump’s speeches in comparison with other prominent political leaders (Wang & Liu, 2017; Zhao, Wu, & Zhang, 2020; Kreis, 2017 and others).

The object of the study is political caricatures of former U.S. President Donald Trump as a subgenre of political discourse. The study is an attempt to analyze the efficient stylistic means of creating Trump’s image in American political cartoons being one of the most available and popular types of cartoons in the world. Still the linguistic analysis needs to be done due to increasing interest to the visual information and along with its influence on the viewers and readers.

Methods and materials

As a research material, 300 political cartoons having Donald Trump as the main character were selected. Today Donald Trump’s name is still popular on the internet, in the newspapers and magazines, and on television notwithstanding his being a former president. A lot of young scientists devote their research to Donald Trump’s personality or speeches (Ross, 2020; Saul, 2019; Liu, 2018 and many others).

The cartoons were taken from the Internet American English websites specializing in political humor covering years from 2016 to 2019. The range of websites includes social networks such as Facebook.com, Twitter.com, personal caricaturists’ websites GorrelArt.com, cartoon sites cagle.com, tr.toolpool.com, tribunecontentagency.com and other media sites theweek.com, thewisdowdaily.com. The cartoon sites were chosen via Google in the sequence as they appeared in the search line. Undoubtedly, today it is the most common and convenient, and worldwide available way to search information by surfing the Internet. The aim was to prove the supposition that cartoonists use expressive means both verbal and non-verbal (visual) ones at every language level to reflect Donald Trump’s presidency. This period was chosen, firstly, due to the fact that 45th US president was elected through the Electoral College, not by popular vote; secondly, due to the community’s reaction to Trump’s personality and policy. “Trump is unique because there has never been nothing like him before, he is completely off the spectrum” (García, 2018: 68).

All the language levels were studied carefully for the verbal component of cartoons and visual means in non-verbal component to reveal the most frequent ones. We chose the most prominent means that helped the cartoonists to create the picturesque interpretation of a political event or image of a political actor.

Using contextual analysis in our research we concentrated our attention on determining the conditions necessary and sufficient to reveal the author’s idea.

Statistical method was implemented to define the frequency of the linguistic means used in the cartoons.

Thus, taking into consideration the content and structure of the text in cartoons, it is also important to analyze a non-verbal component due to expressive possibilities of paralinguistic means, their role and influence upon reader’s interpretation.

Findings and discussion

1. Political cartoon as a sub-genre of political discourse

One of the most important functions of political discourse is the fight for power (Wodak, 2006; Sheigal, 2000). Power in political discourses can be achieved and exercised by both ongoing struggles and/or by co-operation between political actors and institutions aimed at preventing and resolving potential conflicts (Chilton, 2004). The main aim of the language means is to destroy the opponent. One of the crucial keys to victory is the ability to ridicule the enemy. Political cartoons function as a perfect way to achieve the goal.

In the era of globalization, political cartoons are becoming more accessible for readers. Still, this field is understudied as researchers (Hanada Al-Masri, 2015; Oluremi, 2019; Kwon, 2019) devote their works on political cartoons mostly to domestic politics. There were attempts to study political cartoons in such countries as Japan, Nigeria, South Korea, UK, USA and Australia. According to Oluremi (2019), who is studying Nigerian cartoons as the satirical form of communication in modern times, “political humour is one of the tasks of political cartoons and it is prevalent in this media genre because of its communicative potential and humorous potential” (Oluremi, 2019: 67). Hanada Al-Masri studies Jordanian editorial cartoon within a “multimodal approach to context with a consideration of three types of sub-contexts essential to the understanding of the cartoon's message: (1) macro-context, (2) microcontext and (3) dynamic context” (Al-Masri, 2015: 45).Tatjana Đurović in her paper addresses the topic of Brexit unfolded in pictorial and multimodal discourse in media to explore how this topic is communicated via metaphors in political cartoons (Silaski, Durovic, 2019).

A. J Wright (2002), V. Tsakona (2009), H. Aliefendioglu, Y. Arslan (2011) investigate the humor effect in cartoon.

However, we need more detailed insight into the means that convey the information presupposed in political cartoons. We have to answer at least these questions: What types of means are appropriate to use in the context? What are the consequences of this usage to the audience? In order to do so, this article dwells on the features and peculiarities of political cartoons as a sub-genre of political discourse and the most prominent means concerning visual and verbal components.

2. Features and peculiarities of political cartoons

Nowadays political cartoons, as one of the types of political texts, are broadly used in the media. Cartoons are very popular, addressing many different things at the same time. They serve to entertain, explain, comment and simplify (Charteris-Black, 2017). “The significance of political cartoons also lies in the fact that they are able to give socio-political commentaries on vital areas of reality” (Oluremi, 2019: 67). A cartoon means any image created for humor effect where the author combines fantasy and reality, applies exaggerations, underlines character traits, and uses incongruous comparisons. On the one hand, a caricature is a depiction of reality created with a humorous purpose; on the other hand, it is a reflection of public opinion on the events in the world.

“From the point of view of the language, one of the distinguishing features of a political cartoon is the interaction of verbal, iconic and paralinguistic components within it” (Dugalich, 2018: 156). The non-verbal (visual) component of a cartoon is sometimes more attractive for readers. Thus, the text often serves as a kind of commentary or complementary part to the visual component. Visual component is a complex and important part of a cartoon. Symbols, figures, tables, photos can be used to present the main idea of the cartoon. Non-verbal means have high information capacity and pragmatic potential as far as it takes less time for the reader to grasp the message, and the main idea is conveyed without loss of meaning.

In the following section, applying CDA, political cartoons selected from the Internet were analyzed with the emphasis on verbal components at phonetic, lexical, and syntactic levels and non-verbal means in order to stress linguistically expressed peculiarities of Trump’s presidency and his personality.

3. Expressive means in the verbal component

The expressive means in the verbal part of a political cartoon include phonetic means, graphics, lexical and syntactical forms used with the intention to intensify the utterance logically and emotionally. Since the main semantic load in the cartoon is performed by the visual component, graphic means are eye-catching in the verbal component. “Another important component that cartoons as visuals can provide is their ability to show non-verbal aspects of communication: facial expressions, body postures and relevant gestures” (Khir, 2012: 102). Among them there are different types of font and color which reflect the author's style and attract reader’s attention.

Generally, the color of a media text is black, different “colors in a text are not an obligatory element, but they have an appealing and semantic function and enter into complementary relationship with the verbal component. The correlation of the color and the meaning characterizes the national-cultural specificity of the ethnos, which leads to the problem of decoding the visual semantic sign” (Dugalich, 2018: 167).

The color reflects the intonation of the utterance and emotional mood of the speaker. The most frequently used color is red. It is one of the basic colors, and it is the one that immediately draws the reader’s attention. Violet and pink can also occur. Picture 1 proves this statement. Donald Trump says “I AM NOT A CROOK!”, “BUT IF I AM I CAN PARDON MYSELF”. The color gives an ironical shade to the utterance. Firstly, the red color attracts attention, and secondly, it is a sign of a problem or/and danger. Colorful cartoons are interesting for readers as they provide additional information for understanding.

Picture 1. Donald Trump says “I’m not a crook”[1]

The most common phonetic means of the text in a political cartoon are sound effects expressed in the quantity increase of vowels or consonants. As a rule, such examples are given in the speech of the characters, when the author tries to render an emotional mood or special attitude towards the object of speech. These features are to create peculiarities in the manner of speech by intensifying the utterance emotionally or logically. The exclamation “BLEEDING!..BLATHER!..BLAH!..BLAH!..BLAH!” belongs to Donald Trump, when he refuses to listen to the Republicans’ arguments. The implication is to illustrate Trump’s reluctance to listen to their words and his lack of arguments.

Picture2. Bleeding! Blather![2]

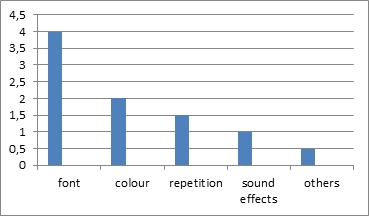

The bar chart (see. Figure 1) presents the frequency of phonetic and graphic means usage (font, colour, repetition, sound effects and other means) found in 300 political cartoons on Donald Trump covering the period from 2016 to 2019. It is evident from the chart that the most frequently used one is the font. It appears 25 times in the above-mentioned number of the cartoons. The use of colors is fairly similar to the use of repetitions in cartoons (16-18 times). The next popular means for caricaturists to use is sound effects though it is as twice low as the usage of the font (10 times). The sound effects are presented only 6 times. The other phonetic means are one fifth the total.

If the graphic and phonetic means are expressed only in the verbal component of a cartoon, the lexical features are closely connected with the visual component. Therefore, the study of this level should be done with the analysis of the visual component.

Figure 1. Means at the phonetic level

The peculiarity of a political cartoon as a type of a political text can be viewed through the levels of language (phonology, morphology and syntax), but only lexical units denoting specific cultural elements help the reader to understand the meaning properly. The text in the cartoon is minimal, so the author has to choose among the variety of lexical means that harmonize and go together with a visual component, and reflect the author’s intention in a striking way.

It is important to note that the lexical level is the most abundant due to its inner expressiveness, and it stands out from other levels. The following bar chart (see Figure 2) shows the usage of lexical means in political cartoons. Neologisms (new words) are on the top in comparison with other means. The language reflects all the changes in political discourse. Each neologism possesses the expressive power with the purpose to impress the audience. They are 30 of all the selected material. While set expressions are frequently used in cartoons, they are far less numerous than neologisms. They are used only 24 times. In the third place on the chart are emphatic words, literary and/or archaic words are fairly similar to them (resp. 15, 12, 10). We can see from the chart that foreign words are scarce in political cartoons (7).

Figure 2.Means at lexical level

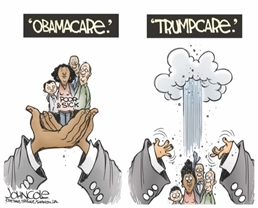

New words are a powerful weapon in the hands of caricaturists. Neologisms are individual words created by the author according to the rules of the word formation on the models that exist in the modern language. The neologisms “Obamacare” and “Trumpcare” are telescopic in nature and are formed by adding the second part of the word “healthcare” to the US Presidents’ names Donald Trump and Barack Obama. These new words represent presidents’ reforms in healthcare and people’s attitude towards them.

The next cartoon (see Picture 3) illustrates the contrast between the actions of two political leaders.

Picture 3. Obamacare vs. Trumpcare[3]

The repeated use of “Trumpcare” in political cartoons indicates that this word is firmly rooted in the English language (AmE), so we can assume that the author’s creativity can cause the appearance of new words in spoken or written language.

Occasionalism is an individual author's word created by a writer in accordance with the rules of the word-formation, and used in the text as a lexical means of emphatic expression. Occasionalisms in political cartoons represent newly appeared concepts, actions, and events. After the word gets a widespread use, it ceases to be an occasionalism. As a stylistic device, they convey an emotional load.

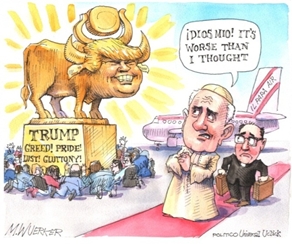

To create an ironic effect the cartoonists borrow words from other languages. In Picture 4, there is an example of Spanish exclamation “Dios Mio (OMG)” emphasizing the degree of Pope Francis’s astonishment at Trump’s vices. On the one hand, the usage of the Spanish exclamation shows the Pope’s Argentinian origin, and, on the other hand, it emphasizes his emotional state.

Picture 4. Papa’s reaction[4]

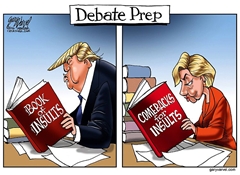

Comparison is a stylistic device taking a peculiar place among the means on the lexical level. The use of comparison as a contrasting of different properties of two or more objects (based on the visual component) is to present a political situation in a colorful way or emphasize the characteristics of a political leader. The distinction between the two forms can arise at all language levels. Comparison in a cartoon is a stylistic means, which helps to choose between the candidates, find a solution, as well as to bring the attitude towards a particular country or policy. For example, Picture 8 presents a comparison of two candidates. There are two candidates running for 2016 Presidency, i.e. Hilary Clinton vs Donald Trump. Mr. Trump is known for his direct opinions and calling names to criticize or comment on the actions of his opponents, media and/or political figures. The meaning of the cartoon is clear: Donald Trump knows how to insult an opponent (He is holding a book of insults) but in contrast, Hillary Clinton is not ready to give up, as she could retaliate by answering back (She is holding a book of comebacks for insults).

Picture 5. Debate Prep[5]

As for the syntactic level, these constructions reveal a certain degree of logical or emotional emphasis (see Figure 3). As it may be seen from the chart, rhetorical questions and exclamatory sentences are presented in political cartoons with a similar proportion, they come 30 times. Aposiopesis ranks second: we come across it 25 times among the selected cartoons while ellipsis and repetition are fairly similar to each other (10 times).

Figure 3.Means of syntactic level

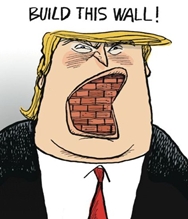

The syntax of the textual component in a cartoon includes units of different language levels from phrases to complex and compound sentences, however, the main forms are a dialogue and a monologue. The interruption of the sentence serves as stylistic expressiveness, and gives the readers an opportunity to appreciate and interpret the text without any explanation. Exclamatory sentences (Picture 6) obtain rich possibilities for creating expressiveness, too. This exclamatory sentence conveys strong emotion and excitement. In comparison with a visual component (Donald Trump’s mouth as a brick wall) the exclamatory sentence “BUILD THIS WALL!” shows Trump’s obsession with the idea of building the wall between Mexico and the USA.

Picture 6. Build this wall[6]

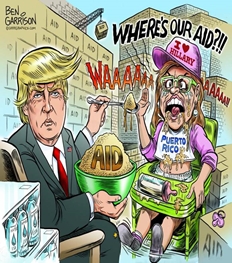

Rhetorical questions make the reader begin a dialogue with the author, argue with him/her, and, thus, find the answer. The following cartoon (Picture 7) is an example of a rhetorical question usage in the text of a cartoon: “WHERE’S OUR AID?!!” With the help of exclamation marks the author underlines the absurdity of the situation.

Picture 7. Where’s our aid[7]

4. Non-verbal expressive means in cartoon

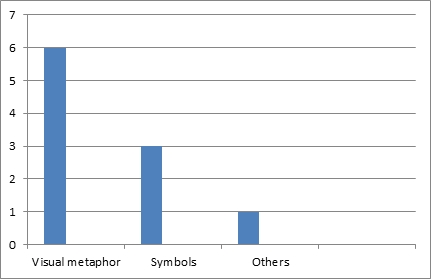

As mentioned above, the most common means of creating expressiveness in the non-verbal component is a visual metaphor. The bar chart (see Figure 4) compares the quantity of visual means used in political cartoons to prove the idea. The chart plainly indicates that a visual metaphor is the most frequently used means in the non-verbal component in 300 selected cartoons. It occurs 20 times in the selected material. Symbols occur less frequently than metaphors (15 times), and other media (tables, charts, graphs, and other visual media) account for a third of the total (5).

Figure 4.Non-verbal means

A visual metaphor is built through the correlation of two visual images as iconic signs. It is important that metaphors used in political cartoons are easily recognized and understood. The metaphor, which you can see in Picture 8, ironically illustrates Donald Trump’s strong intention not to yield to anybody’s persuasion and his adamant commitment to build the wall between the USA and Mexico.

Picture 8. The great wall of Trump[8]

Cartoonists broadly use symbols to present larger concepts or idea. “A symbol in its most general form is a sign in which the primary content is used as an exponent of another, more abstract and culturally valuable content” (Vorkachev, 2021: 4). On the one hand, each image contains information that everyone knows, it saves place and time. On the other hand, these images should be familiar for the audience. The choice of a symbol reflects the political situation in the world; its use depends on the importance of the event. The most common symbols used in cartoons are a donkey and an elephant, being the symbols of the American rival parties. The Republican Party is represented with the Elephant, the Democrats are the donkey. The president of America belongs to the Republican Party. In Picture 9, Donald Trump as a provoker-in-chief challenges the Democrats, symbolized by the donkey, to impeach him.

Picture 9. Provoker-in-chief[9]

Conclusion

This paper is an attempt to present Trump’s image through a political cartoon. The expressive potential in a cartoon is analyzed on the following linguistic levels: phonetic, lexical-grammatical, and syntactic. The most wide-spread means of creating a colorful plot in a political cartoon are antithesis, comparison and neologisms represented at the lexical level in the verbal component along with a visual metaphor in the non-verbal component. The cartoonists may use the combination of verbal and non-verbal means to reach the goal. The usage of these means intends to intensify the emphatic coloring.

This study is a way of seeing Donald Trump political cartoons from a linguistic point of view analyzing separately the verbal means at each language level and non-verbal ones.

Donald Trump for his simple, pompous and repetitive language is rather popular not only among sociologists, but also among linguists. The interest to Donald Trump, his personality and his style of speaking have been attracting caricaturists’ attention in recent years. His manner of speech, his rhetoric and eloquent sentences provoke authors to create vivid cartoons.

A lot of research works are now devoted to the study of political cartoons due to the growing popularity of a cartoon in political communication and its ability to influence the reader in the sphere of his/her political preferences. But little attention has been paid to Donald Trump political cartoons despite their expressive power in political discourse and political communication. The idea behind many of the cartoons is to mock Trump: cartoonists use his words out of the context to present an invented creative plot with humorous shade to the audience. The results of this study prove that expressive means show Donald Trump in a humorous light with his faults and failures both as an ordinary person and as an outstanding politician. Political cartoons help to avoid automatic perception of reality, look at political events from an unexpected point of view and understand more clearly the world of politics.

Hence, these findings intend to enhance the public perception of Trump’s presidency and his character. It may be valuable for the future cartoonists to assort necessary set of means to evoke public interest. The list of expressive means in this study is by no means complete and definitely presents aspirations for further study. The commentaries given in the article are solely based on our understanding and background knowledge of political situation in the USA.

The cartoon genre is developing, new political figures are coming to be estimated in a new way, new words and means appear in the cartoonists’ fund. The above mentioned influence the norms and rules of the language. It would be interesting to investigate the expressive means of the Internet memes and compare them to a traditional, already accepted, cartoon.

[1] URL: http://www.gorrellart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Gorrell06.05.18.jpg

[2] URL: https://c.o0bg.com/rf/image_960w/Boston/2011-2020/2015/08/10/BostonGlobe.com/EditorialOpinion/Images/0811wassermancolor.jpg

[3] URL: http;//media.cagle.com/82/2016/01/16/174168_600.jpg

[4] URL: https://image.cagle.com/196950/1155/196950.png

[5]URL: http://thewisdomdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/1442881923.jpg

[6]URL: https://i.pinimg.com/originals/11/95/e8/1195e81e5bc88001f7e0e27ea994f69b.png

[7]URL: http://whistleblower-newswire.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/image005.jpg

[8]URL: https://i.imgur.com/RcOwYbI.jpg

[9]URL: http:// whistleblower-newswire.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/image005.jpg

Reference lists

Aliefendioglu, H. and Yetin, A. (2011). Don't take it personally, it's just a joke: The masculine media discourse of jokes and cartoons on the Cyprus issue, Women'sStudies International Forum, 34 (2), 101-111. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2010.08.002 (In English)

Al-Masri, H. (2016). Jordanian editorial cartoons: A multimodal approach to the cartoons of Emad Hajjaj, Language & Communication, 50, 45-58. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2016.09.005(In English)

Charteris-Black, J. (2017). Fire Metaphors: Discourses of Awe and Authority, Bloomsbury, London, UK. (In English)

Chilton, P. and Schaffner, C. (2004). Analysing political discourse: Theory and practice, Routledge, London, UK. (In English)

Dijk, T. A. (2004). Discourse and power, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, USA. (In English)

Dugalich, N. M. (2018). Political cartoon as a genre of political discourse, RUDN Journal of Language Studies, Semiotics and Semantics, 9 (1), 158-172. http://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2299-2018-9-1-158-172 (In English)

Dunmire, P. L. (2019). America’s most precious resource: The future in American national identity and foreign policy, Futures, 112. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUTURES.2019.06.007(In English)

Fairclough, N. (2001). Language and power, Longman, London, UK. (In English)

Gabets, A. and Gené, A. (2016). Pragmalinguistic features of American presidents’ inaugural addresses of the last century (1913-2013), Journal of Language and Education, 2 (3), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.17323/2411-7390-2016-2-3-22-31(In English)

García, T. M. (2018). Donald J. Trump: A Critical Discourse Analysis, Estudios Institucionales, 5 (8), 47-73. http://doi.org//10.5944/eeii.vol.5.n.8.2018.21778 (In English)

Karnyushina, V. and Makhina, A. (2017). Lexical and grammatical means of distancing strategy performed in American political discourse, Journal of Language and Education, 3 (1), 85-101. https://doi.org/10.17323/2411-7390-2017-3-1-85-101(In English)

Khir, A. N. (2012). A semantic and pragmatic approach to verb particle constructions used in cartoons and puns, Language Value, 4 (1), 97-117. http://doi.org/10.6035/languagev.2012.4.6 (In English)

Kreis, R. S. (2017). The “Tweet Politics” of President Trump, Journal of Language and Politics, 16, 607-618. http://doi.org/10.1075/JLP.17032.KRE(In English)

Kwon, I. (2019). Conceptual mappings in political cartoons: A comparative study of the case of nuclear crises in US–North Korean relations, Journal of Pragmatics, 143, 10-27. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.021(In English)

Oluremi, T. A. (2019). Pragmeme of Political Humour in Selected Nigerian Political Cartoons, Journal of Language and Education, 5 (4), 66-80. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2019.9682(In English)

Randour, F., Perrez, J. and Reuchamps, M. (2020). Twenty years of research on political discourse: A systematic review and directions for future research, Discourse & Society, 31, 428–443. http://doi.org//10.1177/0957926520903526 (In English)

Ross, A. S. and Caldwell, D. (2020). ‘Going negative’: An APPRAISAL analysis of the rhetoric of Donald Trump on Twitter, Language & Communication, 70, 13-27. http://doi.org//10.1016/j.langcom.2019.09.003 (In English)

Saul, A. and Chase, W. R. (2019). Conversation analysis at the ‘middle region’ of public life: Greetings and the interactional construction of Donald Trump's political persona, Language & Communication, 69, 67-83. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2019.08.001(In English)

Sheigal, E. I. (2000). Semiotika politicheskogo diskursa [Semiotics of Political Discourse], Dc. Sc. Thesis, Volgograd State Pedagogical University, Volgograd, Russia. (In Russian)

Tsakona, V. (2009). Language and image interaction in cartoons: Towards a multimodal theory of humor, Journal of Pragmatics, 41 (6), 1171-1188. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.12.003 (In English)

Vorkachev, S. G. (2021). Semiotics of symbol according to the data of the Russian scientific discourse, Research Result. Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 7 (3), 3-14. http://doi.org/10.18413/2313-8912-2021-7-3-0-1 (In Russian)

Wang, Y. and Liu, H. (2017). Is Trump always rambling like a fourth-grade student? An analysis of stylistic features of Donald Trump’s political discourse during the 2016 election, Discourse & Society, 29, 299-323. http://doi.org//10.1177/0957926517734659(In English)

Wodak, R. (1997). Yazyk. Diskurs. Politika [Language. Discourse. Policy], Peremena, Volgograd, Russia. (In Russian)

Wright, A. J. (2002). See you in the funny papers: Anesthesia in cartoons and comics, International Congress Series, 1242, 547-551. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00785-9(In English)

Zhao, Y., Wu, T. and Zhang, H. (2020). A Typical Politician vs. a Lunatic Businessman: Different Language Styles of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, International Journal of English Linguistics, 10, 26. http://doi.org//10.5539/ijel.v10n2p26(In English)

Zhikhareva, N. A. and Yakovleva, E. P. (2021). Stereotypes as means of influencing mass consciousness in political discourse, Research Result. Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 7 (2), 31-40. http://doi.org/10.18413/2313-8912-2021-7-2-0-4(In English)