ARCHITECTURE OF INFORMATION STRUCTURE: IMPLICATIONS FROM THE T-MODEL ON THE REALISATION ASPECTS OF TOPIC AND FOCUS USING EXAMPLES FROM MODERN STANDARD ARABIC, ENGLISH AND TURKISH LANGUAGES

Aннотация

К сожалению, текст статьи доступен только на Английском

Information Structure

Information structure (IS) as in (Aboh, 2010; Casielles_Suarez 2004; Choi, 1997, Erteschik-Shir, 2007, Fiedler, 2010, Işsever, 2003; Komagata, 1999; Krifka, 2008; Lambrecht, 1994) or information packaging as in (Vallduvi, 1993; Vallduvi, 1996; Vallduvi, 1998) basically refers to describing a sentence and analysing it both linguistically and pragmatically (Lambrecht, 1994). It is also referred to ‘… a structuring of sentences by syntactic, prosodic, or morphological means that arises from the need to meet the communicative demands of a particular context or discourse’ (Vallduvi, 1996, p. 2). IS generally is based on the arguments positioning topic and focus and some other related terms to them (Erteschik, 2007).

This argument within the field of IS is further enriched on assumptions with the aim of examining the system of language yet [languages]. It is an attempt to find matching concepts to language structure i.e. word level, phrase level, sentence level, and text level. By this means, different language components need to find themselves away to interact with one another towards IS or information packaging. This last point is usually referred to the interface of language components to form IS architecture (see Vallduvi, 1993 and Erteschik, 2007). Among these arguments having been trying to build a systematised structure for IS architecture is that based on the T-model.

T-model

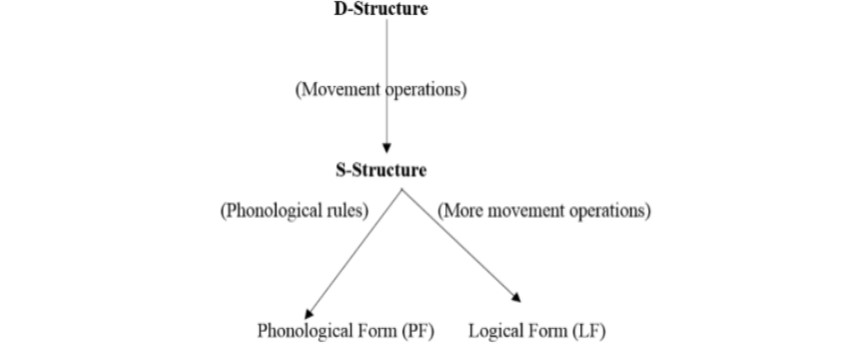

T-model was basically introduced within principles and parameters framework assuming that our linguistic competence is a complex of subsystems of principles, each with one or more parameters of variation, and grammars of particular languages are determined by fixing parameters in these subsystems (Chomsky, 1981; Chomsky, 1986; Chomsky and Lasnik, 1993; Chomsky 1995). Within this framework, the T-model presents the general structures for such framework. The T-model is illustrated in the following diagram:

DS

|

SS

/ \

PF LF

(Phrase structure rules or schema)

Based on this and with reference to the Government Binding theory (GB), language is represented in terms of sounds (phonology) and meaning (semantics). In other words, the representation of language is realised in terms of two forms: the phonological form PF and logical form LF (Chomsky, 1981). Of course, this model seems to be similar to that proposed by Fillmore, 1976 (see Lambrecht, 1994, p. 8).

Furthermore, it is assumed that parameters of languages are binary and the settings of these parameters are ‘mutually exclusive’ (Ayoun, 1998, p. 61). The major interpretation of the T-model is that ‘…in English, DS (°D-structure) is generated by °rewrite rules, or is projected from the rules of °Xbar-theory, and obeys the conditions of °theta-theory and the °Extended Projection Principle. SS (°S-structure) is derived from DS by the repeated application of °affect alpha (e.g. °NP-movement and °Wh-movement), and must meet the demands of °Case theory, and possibly °Binding Theory. LF (°Logical Form) is derived from SS through the application of affect alpha (e.g °QR, Wh-raising (°Wh-in-situ)), and is regarded as the interface with the conceptual system; possibly, LF obeys Binding Theory and is the locus of gamma-checking (°gamma-marking). °PF is derived from SS and is considered the interface with the articulatory-perceptual system. Both PF and LF are subject to the principle of °Full interpretation. The division of labour among the three syntactic levels of representation (DS, SS, LF) is subject to debate, and may vary across languages’ (Chomsky, 1981; Chomsky, 1986; Chomsky and Lasnik, 1993).

Furthermore, it is assumed that parameters of languages are binary and the settings of these parameters are ‘mutually exclusive’ (Ayoun, 1998, p. 61). The major interpretation of the T-model is that ‘…in English, DS (°D-structure) is generated by °rewrite rules, or is projected from the rules of °Xbar-theory, and obeys the conditions of °theta-theory and the °Extended Projection Principle. SS (°S-structure) is derived from DS by the repeated application of °affect alpha (e.g. °NP-movement and °Wh-movement), and must meet the demands of °Case theory, and possibly °Binding Theory. LF (°Logical Form) is derived from SS through the application of affect alpha (e.g °QR, Wh-raising (°Wh-in-situ)), and is regarded as the interface with the conceptual system; possibly, LF obeys Binding Theory and is the locus of gamma-checking (°gamma-marking). °PF is derived from SS and is considered the interface with the articulatory-perceptual system. Both PF and LF are subject to the principle of °Full interpretation. The division of labour among the three syntactic levels of representation (DS, SS, LF) is subject to debate, and may vary across languages’ (Chomsky, 1981; Chomsky, 1986; Chomsky and Lasnik, 1993).

Architecture of Information Structure: Topic vs. Focus

Having this in mind, we now need to have a closer look at the nature of IS and IS architecture especially in terms of topic and focus. To start with the topic, it has been worded differently by difference linguists and researchers. For instance, Gabelentz (1869) in Krifka 2008) refers to topic and comment as ‘the object which the speaker is thinking about’ for the former and ‘what the speaker is thinking about it’ for the latter. Another definition is that ‘topic is what the sentence is about’ (Gundel and Fretheim, 2004, p. 176). Moreover, it is introduced in terms of topicalisation where in different types of topics occur (see table below).

Topic | Conditions |

Stage topics | Hearer and speaker interaction |

Permanent and temporary fixtures | Fixed topics |

Temporarily available topics | Current scenes |

Truth values | Intuition-based topics Subject position Pronouns |

Indefinite DPs | Specific Contrastive Partitive |

Definite DPs | Generally topics |

Within this framework, a distinction is also made between old and given information where the former refers to the referent in the conversation and the latter refers to the referent in the mind. By all means, topics must be given (see Erteschik, 2007). However, what could be a topic and could not be a topic is widely argued be it within a certain language or languages. Many models have been proposed accounting for this argumentative area including the T-model. Also consider that of Strawson-Reinhart (see Erteschik, 2007):

Besides, previous research assumes that if pronouns as mentioned above are topics the multiple topics are possible (see Erteschik, 2007; Krifka, 2008; Lambrecht, 1994). To sum up, what could be a topic and could not be seems to be very arguable though a number of generalisations have been reached! Among these that 1) the topic is contextually determined, 2) scopal relations are context-dependent, 3) sentence contextualisation eliminates scopal ambiguity, and 4) topicalisation is not a uniform phenomenon across languages where topic prominent languages are available: Catalan, subject prominent languages: English and Topic and subject prominent languages: Danish (summarised from see Erteschik, 2007). Now consider these examples for topics where the same topics are shared in the three mentioned languages:

Besides, previous research assumes that if pronouns as mentioned above are topics the multiple topics are possible (see Erteschik, 2007; Krifka, 2008; Lambrecht, 1994). To sum up, what could be a topic and could not be seems to be very arguable though a number of generalisations have been reached! Among these that 1) the topic is contextually determined, 2) scopal relations are context-dependent, 3) sentence contextualisation eliminates scopal ambiguity, and 4) topicalisation is not a uniform phenomenon across languages where topic prominent languages are available: Catalan, subject prominent languages: English and Topic and subject prominent languages: Danish (summarised from see Erteschik, 2007). Now consider these examples for topics where the same topics are shared in the three mentioned languages:

Language | Example |

English | How are you? I am finet |

Turkish | Nasılsın? İyiyim. |

Arabic (standard) | كيف حالك؟ بخير. |

English | It is dark. The moont has disappeared. |

Turkish | Karanlık. Ay kayboldu. |

Arabic (standard) | أنها مظلمة. القمر يوشك أن يختفي. |

English | That chair.t |

Turkish | O koltuk. |

Arabic (standard) | ذاك الكرسي. |

English | Two studentst are intelligent. |

Turkish | İki öğrenci zekidir. |

Arabic (standard) | طالبان ذكيان طالبتان ذكيتان |

The same argument applies to focus as well! Focus is generally referred to ‘what is predicated about’ (Gundel and Fretheim, 2004, p. 176). The focus is also introduced as ‘non-presupposed information in the sentence’ according to Chomsky, Jackendoff and Lambrecht in (Erteschik, 2007, p. 27). Again, focus is being introduced first in terms of the T-model where the focus is derived based on segmental and/or suprasegmental features of speech PF, semantically LF, syntactically, or pragmatically. Consider also the following examples for focus:

Language | Example |

English | Sara left the book on the deskf. |

Turkish | Sara kitabı masayıf bıraktı. |

Arabic (standard) | تركت سارة الكتاب على الماسة. |

T-model and Information Structure

For now we have introduced IS, topic, focus, and the T-model’s nature. Our purpose to view the T-model in relation to IS architecture. In other words, in order to build an IS architecture language elements have to be presented with reference to grammars i.e. T-model. The impact of each component in the T-model on IS must be examined. We need input in order to reach some findings about IS architecture. This input includes sentence structure, and word order. That is to say, we can generalise the concepts of IS but we have to investigate each individually for each language where terms like topicalisation (the possibility to change position of the words without affecting meaning [free word order], topic (a previous piece of information stated by the speaker delivered to the listener). Additionally, the view that topic (old information) and focus (new information) are both intricately related to form IS architecture. The speaker and the hearer presupposition and the topic and focus are entirely effected by text/context. With the T-model’s operational criteria we can introduce the basic terms of IS being supported with grammatical terms. We need features that allow us to decide what could be the topic and what could be the focus where at least one of these features for each must be unique. Consider the following example for focus projecting among Arabic, English and Turkish languages:

Language | Example |

English | Lara read a book. |

Turkish | Lara bir kitabı okudu. |

Arabic (standard) | قرأت لارا كتاباً |

Lara read a bookf.

*Lara a book read.

*Read a book Lara.

Lara bir kitabıf okudu.

Lara kitabıf okudu.

Lara kitapf okudu.

Bir kitabıf, Lara okudu.

قرأت لارا كتاباَ.

لارا قرأت كتاباَ.

كتاباَ, قرأت لارا.

Now going back to the T-model illustrated in the two diagrams above, we can see that while the PF and LF are integrating and interacting with the syntactic component; the PF is not interacting with the LF and vice versa! This is by itself is the first problems as we have already mentioned while accounting for topic and focus that IS is naturally more than PF and LF yet the interaction and/or interface of such components is highly required. The following tables is a summary for the T-model major problems mainly in relation to violating the inclusiveness feature and approaches which attempted topic and focus interaction based on this model:

Approach | Minus point |

| Topic assignment is lacking Topic and focus interaction is lacking |

| Explanation of topic of focus relationship is lacking |

| IS has optionality movement triggered by IS |

| Indirectly equal to topic and focus Topic and focus interaction is lacking

|

| Phonology based-view |

| Topic issue is lacking |

| Such forms are neither PF nor LF; hierarchical structures |

| Syntax must proceed PF but they introduced PF over syntax |

| It gives more focus to morphology |

To conclude, we can see that the interaction of both the PF and the LF is highly required in order to achieve IS architecture and avoid the violation of IS features i.e. inclusiveness and/or interaction of topic and focus. By this means, the T-model doesn’t really yet fully introduce a perfect model for the IS architecture. This model was further modified and enhanced by different minor models.

Focus: Language-based realisation

Both focus and topic are introduced as the major issue of IS. In the first question, we introduced them both and our reference to the focus was as the ‘complement of topic’ and the part which presents ‘new information’, ‘new knowledge’, and/or ‘pragmatic insertion’ (Lambrecht, 1994, p. 206). Krifika uses the definition that focus ‘indicates the presentence of alternatives that are relevant for the interpretation of linguistic expressions’ (2008). From a semantic perspective, it is defined as the ‘non-presupposed information in the sentence’ as in (Erteschik, 2007, p. 27). Now, consider the following examples for focus in Arabic, English and Turkish languages:

Language | Example |

English | Dana lives in [Ankaraf]. |

Turkish | Dana [Ankaraf]'da yaşıyor. |

Arabic (standard) | تعيش دانا في أنقره. |

Actually many types of focus have been introduced by different linguists and researchers i.e. expression focus and denotation focus (Krifka, 2008), contrastive and information focuses (Ereteschik, 2007), contrastive focus and identificational focus (Szendroi, 2004), information focus (presentational focus) and contrastive focus (identificational focus) (Aboh, Corver, Dyakonova and van Koppen, 2010), contrastive-focus and presentational-focus (Işsever, 2003), narrow focus, constituent focus and constrastive focus (Vallduvi, 1993), completive focus and contrastive focus (Choi, 1997), etc.. Thus, our discussion below will be focused on two types of focus and we will refer to them as contrastive focus and presentational focus with examples in different languages. Our presented discussion will be based on the above presented sources.

Gondel and Fretheim state ‘both information focus and contrastive focus are coded by some type of linguistic prominence across languages, a fact that no doubt has contributed to a blurring of the distinction between these two categories’ (2004, p. 181). In these two examples, the pitch or say the suprasegmental features of speech are controlling the distinction between contrastive focus and presentational focus.

Who made all this great food?

[SARA] presentational focus made the [FOOD] contrastive focus.

The syntactic marking can also play role in the distinction between contrastive and presentational focuses (see Gondel and Fretheim, 2004). Consider the following example:

Which book do you want to read?

[That one] contrastive focus on the desk.

I want to read [that book] presentational focus on the desk.

Choi claims ‘the regular, pure new information type of focus [is] completive focus and the alternative set evoking focus [is] contrastive focus [and ] the distinctive feature between [them] is discourse prominence’ (1997, p. 5). Consider the following example:

Do you want the red pen or the black pen?

I want the [RED PEN]. (Selecting)

Since Sara packed her clothes, study materials and Laptop, she will leave.

No, she just packed her [CLOTHES]. (Restricting)

Since Sam is watching a movie, so he will be happy.

No, he is not just watching a movie, he is also having [PIZZA]. (Expanding)

Sara is SINGLE but Laura is MARRIED. (Parallel)

He named his baby [SAM] presentational focus.

[SAM] contrastive focus he named his baby.

Göksel and Ozsoy in their study attempted to distinguish between sentential stress and focus stress in Turkish with an account to contrastive focus. The following example is quoted from this study; The second example (b) according to the researchers is an example of contrastive focus for Turkish.

a.Ev-e GİT-me-di-m. b.EV-E git-me-di-m. c.EV-E git-ti-m.

home-DAT go-NEG-PAST-1 home-DAT go-NEG-PAST-1 home-DAT go-past-1

I diidn’t go home. I didn’t go HOME.

I went HOME/home.

At the same sense, Işsever (2003) proposes that ‘the word order–prosody interface reveals that presentational-focus and contrastive-focus are two distinct phenomena in Turkish, which are marked by different focusing strategies, i.e. syntactic and prosodic’ (p. 1025). The author presents also that while the completive focus does not allow scrambling of focus element the contrastive focus does.

On the other hand, as in (Aboh, Corver, Dyakonova and van Koppen, 2010) the presentational focus ‘can pragmatically be defined as new, non-presupposed information, [and the contrastive focus] can informally be characterized as evoking a suitable ‘‘subset of the set of contextually or situationally given elements for which the predicate phrase can potentially hold’ (p. 785). Examples from different language were presented e.g. Italian, Polish, Turkish, English, etc. and the authors conclude that ‘both information focus and contrastive focus are attested within the nominal domain … the noun phrase, just like the sentence, may be interpreted as a syntactic domain in which information structure is active’ (ibid, p. 788).

Italian: Ia casa SUA, non tua. (The house is hers, not yours.) [Pragmatic effect and focalization)

Polish: piękne kobiety (beautiful woman/ a beautiful woman) [Pragmatic effect]

Turkish: BIR büyük ev/ (one bige house, a big house) büyük BİR ev/ (big a house, a BIG house) (Word order effect)

Arabic: كتاباً/ كتاباَ واحداً (ketaban [a book] ketaban waehdan [one book] (Syntactic effect)

Also Szendroi accounted for focus types including the contrastive and informational/ presentational ones. Her approach was based on the interface approach where phonological aspects, morphological aspects, semantic aspects, syntactic aspects pragmatic aspects are integrated. Consider the following examples. This [*] means that such structures are ill-structured even if they are acceptable following the transformational generative grammar (TGG). The only possible mean towards transferring these hidden information is using the suprasegmental features of speech while communicating orally where the voice will go up/down or a certain word will be emphasised to reflect whether a certain piece of information is being given (presentational/ contrastive). The discourse component will also help supporting this packing and communication between the listener the speaker. Erteschik-Shir also proposes that ‘the contrastive focus which relates to a contextual context set is more topical than the informational focus which has no such contextual relation. Here again [old] precedes [new]’ (2007, p. 98).

What did you do?

English: I did the [HOMEWORK]. *[HOMEWORK] I did.

Arabic: كتبت الواجب. الواجب كتبت.

Turkish: ÖDEVİ yaptım. ÖDEV yaptım. *Yaptım, ÖDEVİ. *Yaptım, ÖDEV.

In addition to what have been mentioned above, Erteschik-Shir (2007) introduces the contrastive focus as that which ‘focuses one element of the contrast set and eliminates the other alternatives [and] ranges over contextually restricted sets... [it is] referred to as “narrow,” “exhaustive,” or “exclusive” foci’ (p. 29). Comparatively, the presentational focus or the ‘noncontrastive foci are referred to as informational foci or presentational foci (when they occur in existentials)’ (ibid). In this regard Choi (1997) presented the following IS features where both the contrastive and presentational focuses are included:

| +Prom | −Prom |

− New | Topic | Tail |

+New | Contrastive Focus | Completive Focus |

To all intents and purposes, we have seen that the contrastive focus is entirely different from the presentational focus on the basis of phonological features, semantic features, morphological features, syntactic features, pragmatic features and/or even discourse features. Besides and as we have illustrated above the effect of these features could is interchangeable according to the type of language and its linguistic system.

Scrambling

We have already introduced IS above and more importantly we referred to IS as the output resulting from the interface among language components i.e. PF, LF, etc.. This interface which is guided and governed by certain parameters derived from different theories could be phonological, syntactic, morphological, semantic, pragmatic, etc.. Among these effects which directly affect the formation and structure of IS is scrambling.

Essentially and according to Erteschik-Shir (2007), scrambling is a terms which has been used first by Ross (1967) as ‘a stylistic rule’ but was defined by Bailyn as ‘a general cover term for the process that derives non-canonical word order patterns in so called ‘free word order language’ such as Japanese, Russian, German, Hindi and many others… [where] constituents can appear in a variety of surface orders without changing the core meaning of the sentence’ Bailyn 2002 in Erteschik-Shir (2007, p. 124). Besides yet when compared to topicalisation scrambling is characterised by ‘that it is not necessarily restricted to root clauses, yet it is not always easy to tease apart particular cases in which an element is “scrambled” to the left periphery’ (ibid, p. 125).

Needless to consider the fact this argument of scrambling and its effect on IS is mainly based on the view of sentence structure where in languages are described in terms of the order of the sentence elements and the flexibility of such elements to be moved without affecting the core meaning of the sentence. The following structures are usually the basic formation of discussing scrambling in relation to IS:

Consider the following examples for such structures:

English: [Ahmed]S [read]V a [book]O.

French: [Ahmed]S [lire]V un [livre]O.

Turkish: [Ahmed]S bir [kitap]O [okudu]V.

Arabic: . [كتاباَ]O [احمدٌ]S [قرأَ]V

.[كتاباَ]O [قرأَ]V [احمدٌ]S

Actually, scrambling can take different movements e.g. object shift, clause bound scrambling and long distance scrambling. A different classification is brought by Komagata (1999) who proposes that scrambling ‘is often classified as local (clause-bounded) and long-distance (unbounded) varieties states’ (p. 123). He also goes on stating that ‘languages like German and Turkish are known for their extremely flexible word order’ (ibid, p. 100). The author presented this structure:

(NP1:::NPm)scrambled Vm…V1

Consider the following examples for local and long distance scrambling in Japanese quoted from (Komagata (1999).

[Naomi-ni Ken-ga ageta ] mono-wa banana-da.

Naomi-DAT Ken-NOM gave thing-TOP banana-COP (scrambled)

“The thing which Ken gave to Naomi was banana.”

Bananai-wa Naomi-ga [ Erika-ga ti tabeta ] -to omotta.

banana-TOP Naomi-NOM Erika-NOM ate -COMP thought (fronted)

“The banana, Naomi thought Erika ate.”

In regard to the interaction and effect of scrambling on IS, Choi (1997) proposes that scrambling ‘is motivated by IS’ and has the following ‘ground elements’ (p. 1037): 1) ground elements, both topic and tail, can scramble and 2) topic more easily scrambles than tail. (ibid). Furthermore and in support of the scrambling phenomenon and its effect on IS mainly the focus, Işsever (2003) adopts Choi’s parameters in regard to scrambling where the former assumes that scrambling of focus elements is not possible in the completive focus but it is possible in the contrastive focus. According to the author, such parameter or say [generalisations] are supported by the structure of Turkish. See also Işsever (2006) who argues against the view that ‘non-Case-marked and/or [-specific] NPs cannot be scrambled in Turkish’ concluding that this seems to be possible stating that such NPs are ‘free to scramble into the post-verbal field when they have Topic-features’ (p. 42).

Moreover, Erteschik-Shir (2007) includes Russian language among the free word order languages clarifying the effect of scrambling on IS. She declares, ‘Russian is known to be non-configurational, with few restrictions, if any on word order’ (p. 125). The following six orders are possible in Russian according to van Gelderen (2003, p. 35):

Ivan kupil knigu

Ivan.NOM bought book.ACC

Ivan knigu kupil

Ivan book bought

Knigu Ivan kupil

book Ivan bought

Knigu kupil Ivan

book bought Ivan

Kupil Ivan knigu

bought Ivan book

Kupil knigu Ivan

bought book Ivan

“Ivan bought the/a book”

Above all, Van Gelderen (2003) emphasises that ‘scrambling as movement driven by IS’ (p. 104). Erteschik-Shir (2007) quotes that van Gelderen concludes ‘the orders SOV, SVO, and O, VS …are therefore accounted for by “normal” syntactic means[and] the other three orders … are a result of linearization at PF according to IS requirements’ (p. 129). Therefore, Russian which allows such different scrambling for its rich structure of morphology; Japanese which is also a scrambled language does not have this flexibility and allowance of early spell out due to that fact that ‘it is rigidly a verb-final language and early spell-out would predict word orders in which the verb would not remain in final position’ van Gelderen in Erteschik-Shir (2007, p. 131).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we could clearly assume that scrambling as a linguistic and more specifically syntactic phenomenon (affected by morphology) greatly interact with IS especially when accounting for topic and focus issues. The focus location in particular can be rule-governed with the support of the scrambling parameters. This effect is no doubt more common and operational in languages of free word order e.g. Russian, German, Arabic, Japanese, Turkish, etc..

Информация о конфликте интересов: авторы не имеют конфликтов интересов для декларации.

Information of conflict of interests: authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Список литературы

Список использованной литературы появится позже.