Linguomental anthroposphere in focus of comparative linguocultural analysis

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to identify the peculiarities of linguomental anthroposphere in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures. The scientific novelty of the research lies in the fact that common and national-cultural differences of subsphere FAMILY, EMOTIONS, VALUES in different languages are distinguished. The material of our research was lexicographic and phraseological sources of the Russian, Ukrainian and English languages, as well as the data of the psycholinguistic experiment. It was proved that the linguocognitive structure of subsphere FAMILY in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures is presented by four categorical blocks. The results of the psycholinguistic experiment demonstrate, for instance, that the Russian and Ukrainian speakers consider the family as more patriarchal one while the British and Americans associate family with equality of partners. We established that good in the naive linguistic pictures of the world is universally associated with positive notions of kindness, mercy, goodness, virtue. Evil is also a universal category in the linguistic consciousness, associated with bad, disgusting: injustice, dishonesty, indifference, immorality. We found out that the truth is associated with honesty (Ukrainian чесність, Russian честность), and the main associations of lie are semantic synonyms: Russian обман, неправда, Ukrainian брехня, English dishonesty, deceit. Kindness as a quality of a good person comes first for the Russian, British and American speakers. For Ukrainians, honesty is more important than kindness. Generosity is an indicator of a good person for almost 50% of English and American respondents, and for 15-20% respondents from Russia, Ukraine and the USA.

Keywords: Linguomental Anthroposphere, Linguoculture, Categorization, Conceptualization, Psycholinguistic Experiment

Introduction

Nowadays, the anthropocentric paradigm of research has focused on humanitarian knowledge. Linguistics is in the vanguard in this respect: the anthropocentric paradigm directs the present-day study of language phenomena in connection with their bearer – man (ethnos, nation).

Any national language predetermines its speakers’ perception and is a kind of worldview reference point. We perceive the world exactly as our native language prompts us. This idea of W. von Humboldt, which was expressed by the German linguist and philosopher back in the XIX century, has become an axiom in modern linguistics, focused on the study of a person in language and language in a person (Humboldt, 1999). The function of the man as the creator of language – a universal sign system, which accumulates in itself customs, traditions, beliefs, specific spiritual and material realities, standards of life in society peculiar to a certain ethnos, i.e. all components of national culture, is also determinative.

According to anthropocentric paradigm, a man perceives, arranges, and classifies the world according to his own needs and values, through awareness of himself and his practical and theoretical activities. The Russian scholar Е. Kubryakova argues that in most cases the segmentation of the world is conditioned by language, which gives this operation a categorizing and linguistic character (Kubryakova, 2004).

The human factor in language is evident in the reconstruction of linguistic and conceptual pictures of the world, i.e. when addressing the processes of figurative comprehension, organization and expression by language signs of such ontological constants as life, death, love, happiness, family, well-being, disease, the relationship of the person and society, the perception of friend and foe, the idea of childhood, youth, old age, attitude to work, to wealth and poverty, interpretation of freedom, cultural values, etc.

Undoubtedly, the processes of cognition, categorization, conceptualization and, accordingly, verbalization of the world are influenced by both natural (geographical, climatic, etc.) and cultural (in a broad sense) factors, and the level of world cognition, which, in many cases, depends on the civilizational measurement of linguoculture. It is these conditions that determine the ways of forming national linguistic and conceptual pictures of the world.

With significant differences between national linguistic and conceptual pictures of the world we can talk about the existence of certain semantic universals. One of the linguocultural dominants is the linguomental anthroposphere by which we understand a linguocognitive essence reflecting mental and psychic processes of human consciousness, including conventional and national-cultural perceptions of reality. The ontological significance of any reality in the system of cultural values is, not without reason, defined precisely through the degree of interaction of a man with this reality.

Thus, the principle of anthropocentrism has defined the priorities of present-day linguistics, aimed at the study of the subject, the linguistic personality in all aspects of its manifestation (in particular linguistic consciousness, linguistic and conceptual world pictures). Anthropocentrism of language is a universally recognized phenomenon, which affects the processes of categorization and conceptualization of the world and, accordingly, the verbalization of objects, phenomena and actions, features important for human existence. The reconstruction of anthropologically oriented linguistic and conceptual pictures of the world is characterized by a dual orientation: from the external linguistic denotation to the conceptualized representation of the object of reality and vice versa. The “human orientation” becomes especially noticeable when studying the ways of interpretation of anthropocentric vocabulary, the semantics of which contains the cognitive attribute “man”, and the processes of secondary anthropologization. The study of linguistic phenomena from the prism of human personality as a point of reference makes it possible to form conclusions about the specificity of language as a determining essence of homo sapiens, which creates a picture of the world, and about cognition of a man in his multidimensionality, a man as the main value of present culture (Agha, 2006; Duranti, 1997; Sorlin & Gardelle, 2018; Sousa & Pennycook, 2018; Tyurkan, 2015; Wortham, 2008). According to V. Maslova, today we can already see “the need to create a unified theory of man, his language, nature and culture, which is called the second nature. It is possible to assume that in the near future such an integrative science based on linguistics will appear, for only linguistics can play the role of a methodological science, as it has better developed research methods than other humanities. As the development of modern sciences shows, it is their polyphony that promises significant breakthroughs in the future” (Maslova, 2019).

The object of our research is the linguomental anthroposphere in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures. The structure of the linguomental anthroposphere includes a huge number of concepts and phenomena related to human activity, which, in turn, are combined into numerous subspheres. It is impossible to describe all of them in a single scientific work. Our attention is focused on the basic, fundamental, universal and nationally specific linguistic spaces: FAMILY, EMOTIONS, VALUES. Each of these linguomental subspheres is also characterized by a marked structural diversity. Our study analyzes: the generic subsphere FAMILY, emotive subspheres reflecting the basic emotions of joy, sadness, fear and the human moral trait – courage as the antipode of fear, as well as the basic axiological subspheres in the opposition: good :: evil, truth :: lie, friend :: foe.

The study is aimed at analyzing peculiarities of linguomental anthroposphere in lexicographic, figurative and naive linguistic world pictures by representatives of closely and non-closely related linguocultures (in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures).

Materials and methods

The material of our research was lexicographic and phraseological sources of the Russian, Ukrainian and English languages, as well as the data of our psycholinguistic experiment. In total, 830 people took part in our experimental research, of whom 272 were representatives of the Russian, 216 of the Ukrainian, 168 of the British and 174 of the American linguocultures.

“The psycholinguistic experiment included the following stages: preparatory, immediate experimental and analytical-generalizing. For each of these stages, tasks, deadlines, and expected results were defined. So, at the preparatory stage of the experiment, its goal and objectives were formulated to ensure its achievement, questionnaires were developed for participants in Russian, Ukrainian and English. In the course of the immediate experimental stage, the respondents filled out the questionnaires offered to them. During the analytical-generalizing stage, we processed the data obtained, entered them into appropriate tables, and formulated conclusions” (Sergienko, Gramma, 2019).

The questionnaire to study the linguomental subsphere FAMILY consisted of 14 open-ended questions. For example, the participants of the experiment were asked about associations the words connected with the name of kinship in the corresponding linguoculture (stimulus word – response word) evoke in them, they were asked to write a noun, an adjective, a verb, which, in their opinion, most accurately characterize words that are names of kinship, to rank a number of qualities of a person concerning close relatives (mother, father, grandmother, grandfather), to give their own definitions of words which are names of close and distant kinship, to determine who, in their opinion, makes up a family, to define what “civil marriage” is and whether such a form of co-habitation is a family, to share phraseological expressions, proverbs, sayings about the family and its members that they know, to answer questions about who, in their opinion, are family, close and distant relatives, to find out who is the head of the family and whether people who are not in blood or in non-blood biological relationship can be considered family, indicating concrete examples.

To study the peculiarities of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of emotive subspheres, the participants of our psycholinguistic experiment were offered a questionnaire consisting of 7 open-ended questions. The respondents – the bearers of Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures – were required to give their own definitions of such notions as “joy”, “sadness”, “courage” and “fear”, to select synonyms to these words in corresponding languages, to express their associations with these words (word-stimulus – word-reaction), to answer the questions “What usually arouses joyful feelings in you?”, “What makes you sad?”, “What action can you call brave?”, “What are you afraid of most of all?”.

In order to study the peculiarities of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of axiological subspheres, the respondents of the analyzed linguocultures were required to specify what associations the words “good”, “evil”, “truth”, “lie” (their lexical equivalents in Russian and Ukrainian) evoke in them, explain what, in their opinion, is the good, evil, truth, lie, enumerate qualities of good and bad people, name famous (public) people whom they consider good and bad, and explain their point of view.

According to the psycholinguistic experiment the respondents participated anonymously with the only restriction of being at least 18 years. The printed and electronic questionnaires were proposed for respondents in Russia, Ukraine, Great Britain, and the United States (also posted on our personal pages in social networks and a variety of thematic groups). The completed questionnaires were posted or e-mailed back to our addresses.

To analyze the results of the questionnaire, we selected only those questionnaires in which the respondents gave answers to more than 50%. This was done because the experimental stage of the research took place without the direct participation of the experimenter: we could not know the reasons why our respondents could not (did not want to) answer most of the questions asked in the questionnaire (whether it was due to inattention, lack of time, lack of desire, difficulty in providing answers, etc.). Taking such questionnaires into account in the experiment could have a significant impact on the reliability of the data obtained and their statistical significance.

The methodology included the following stages:

1. The analysis of linguomental anthroposphere in the lexicographic linguistic world picture (based on the study of lexicographic sources, corpus and phraseology).

2. The study of metaphorical categorization and conceptualization.

3. The psycholinguistic experiment.

4. The statistics processing.

5. The perspectives of the research (Sergienko, 2019).

We used the following research methods:

- linguistic description and observation for establishing the corpus of the analyzed units;

- semantic analysis of linguistic units;

- contrastive (comparative) analysis to identify the common and the different in the use of linguistic means in closely related and non-closely related languages; it established, first of all, contrastive relations at all linguistic levels);

- sociolinguistic methods (questionnaires, surveys, interviews, etc.) to establish a determinative connection between the formation of the analyzed language units and the socio-cultural factors in synchronous and diachronic research;

- psycholinguistic experiment (free associative experiment and the method of reflexive analysis of concepts) to study the peculiarities of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of linguomental anthroposphere in the naive linguistic world pictures of the Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures.

Results

The results of our research can be briefly formulated as follows:

1. Linguomental anthroposphere is defined as multidimensional and multilevel linguocognitive entity.

2. Linguomental subsphere FAMILY as a part of the linguomental anthroposphere is a linguocognitive essence, which reflects generic relations between close people (relatives, friends, colleagues, etc.)., which is linguistically represented by a variety of lexico-semantic and phraseological units of the language and which has linguocultural specificity of perception and expression.

3. There are four linguocognitive categorical blocks in the structure of linguomental subsphere FAMILY, represented in all the analyzed linguocultures, which should be understood as linguomental structure, lexico-semantic and phraseological content of which reflects the linguocultural specificity of the linguistic personality's perception of certain linguomental spheres and their components, namely:

a) family as a jointly living community of blood and/or non-blood relatives;

b) family as a cumulative community of all blood and non-blood relatives;

c) family as a labor (professional) collective;

d) family as a social and cultural community.

4. The core of the linguomental subsphere FAMILY in the lexicographic and figurative linguistic world pictures are all the verbalizers of the meaning “family as a jointly living community of blood and/or non-blood relatives”; the near-core zone is represented by the nominations of kinship and properties, united by the meanings “family as a cumulative community of all blood and non-blood relatives”, “family as a labor (professional) collective”, “family as a social and cultural community”. Because of some lexemes of the near-core zone repeat the components of the core zone, the partial inter-presentation of both zones in all the analyzed linguocultures. The periphery of this linguomental subsphere consists of metaphorical kinship nominations. The near periphery are lexemes and phrases representing the category “family as a labor (professional) collective”, and the far periphery are metaphorical nominations representing the category “family as a social and cultural community”.

5. Despite the obvious universality of the linguomental subsphere FAMILY, the distinctive peculiarities are obvious in the naive linguistic world pictures, which is caused by the linguocultural specificity. The representatives of Russian and Ukrainian linguocultures perceive the structure of family wider than the representatives of British and American linguocultures, who basically consider their close and blood relatives as family.

In the minds of the representatives of the Eastern Slavic linguistic cultures a patriarchal understanding of the family is widespread (the dominant role of the man (husband) in the family), while for the British and Americans equality of partners in marriage is obvious.

6. The core of the emotive subsphere of JOY in the Russian linguoculture is the lexeme радость, in the Ukrainian linguoculture – the lexeme радість, in the British and American linguocultures – the lexeme joy with the semantic features common to all the analyzed linguocultures: “state”, “feeling”, “emotion”, “emotion causer”, “intensity”, “external form of manifestation”. The near-core zone includes the most frequent synonyms and derivatives. The linguocognitive associations in the emotive subsphere JOY in the representatives of all the four linguocultures show a marked semantic similarity with insignificant differences on the linguocultural level.

7. In the lexicographic and figurative linguistic world pictures it seems possible to distinguish two main understandings of sadness in the analyzed linguocultures: 1) the feeling of grief, sorrow, unhappy mood; 2) the source of grief, sorrow.

Linguomental subsphere SADNESS is represented more widely in Russian and Ukrainian linguocultures, in particular in their lexical, phraseological and fiction collections, than in the British and American ones.

8. The linguomental subsphere COURAGE in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures is represented by different parts of speech: adjectives, nouns, verbs and adverbs. The core of this subsphere is represented by the following lexical units: Russian – смелость,храбрость, отвага, отважность, безбоязненность, бесстрашие, бестрепетность, неустрашимость, доблесть, героизм, геройство, дерзость, дерзкость, дерзновенность, решимость, решительность, удаль, мужество, мужественность, предприимчивость, самонадеянность, самоуверенность, энергия, присутствие духа, подъем духа, кураж, дерзновение, легкость, неприличность, оригинальность, дородность, отчаянность, пикантность, рискованность, предприимчивость, фривольность, новизна, бедовость, Ukrainian – смілість, хоробрість, відвага, відважність, мужність, молодецтво, безстрашність, відчайдушність, зухвалість, зухвальство, безумство, дерзновенність, звага, рішучість, English – bravery, brave, boldness, bold, courage, courageous.

The levels of the periphery of this linguomental subsphere are quite extensive in linguistic material, as they cover a huge layer of information, for the verbalization of which linguistic means of different semantic orientation are needed.

The concepts of courage, bravery, courage, valor in idiomatic terms are interchangeable in all the analyzed linguocultures, and their semantics is associated with the peculiarities of human behavior in a situation of danger.

The structure of the linguomental subsphere COURAGE consists of the following categorical blocks 1) “bold in a situation of danger”, 2) “bold in communication”, 3) “bold in professional or creative activities”.

The emotive subsphere COURAGE in the linguomental anthroposphere in the naive linguistic world pictures of the representatives of Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures reveals linguocognitive similarity with some insignificant differences across closely related and non-closely related linguocultures.

9. The emotive subsphere FEAR is a multidimensional culturally marked mental-affective formation, which has conceptual, figurative and axiological content and which is actualized in speech through nomination, description and expressiveness.

The core of the analyzed emotive subsphere in the Russian and Ukrainian linguocultures is the noun страх, while the peripheral zone consists of lexemes in synonymic, antonymic relations, paremics and speech constructions demonstrating different figurative and evaluative connotations of this emotion.

The core of the subsphere FEAR in the British and American linguocultures is the lexeme fear, and the near-core zone includes synonymous lexemes fright, horror, terror, dread, dismay, apprehension, awe, scare, alarm, consternation, trepidation.

The universal emotion “fear” in the analyzed linguocultures has a high potential of means of verbalization, which find their embodiment in synonymic rows, metaphorical structures and paremic constructions of the studied linguocultures.

The emotive subsphere FEAR in the naïve language world pictures is assessed by obvious lexical and semantic diversity of its associations in closely related and non-closely related linguocultures.

10. The semantic range of the moral and evaluative categories of the good and the evil in each of the studied linguocultures includes both positive and negative connotations, which indicates the parallelism of the associative use of these categories. In all the four linguocultures these axiological subspheres are symmetrical: the good is what is good for a person, and the evil is what is bad for a person, the good is associated with well-being, the evil – with war, hostility. The good denotes the higher moral virtue, the evil – the highest transgression, the vice. In English linguocultures good (goodness) and evil have wide semantics, which indicates that they can display more features and characteristics of the same phenomenon, have high compatibility with other words of the language, while good and evil in Russian and Ukrainian linguocultures convey more specific concepts.

The good in the naive linguistic pictures of the world is assessed positively and associated with positive notions of kindness, mercy, goodness, virtue. The evil is also a universal category in the linguistic consciousness of the representatives of closely relate and non-closely related linguocultures, associated with something negative, bad, disgusting: injustice, dishonesty, indifference, immorality.

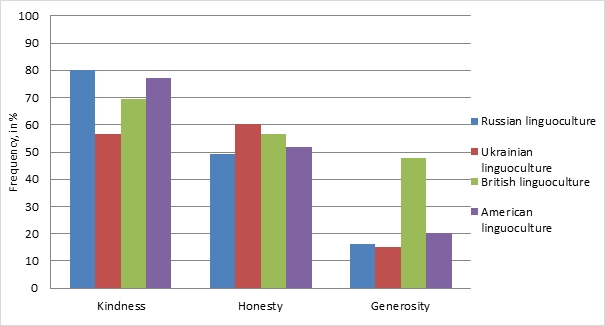

Figure 1. Qualitative representation of the main qualities of a good person (according to psycholinguistic experiment data)

As Figure 1 demonstrates, kindness as a quality of a good person comes first for the speakers of Russian, British and American linguocultures who took part in our experiment. For Ukrainians, such quality of a good person as honesty is more important than kindness. For the representatives of the remaining linguocultures we studied this quality takes the second place. Generosity is an indicator of a good person for almost a half of the respondents from Great Britain, while their colleagues from Russia, Ukraine and the USA consider this quality less important (the range is from 15% to 20% of the answers).

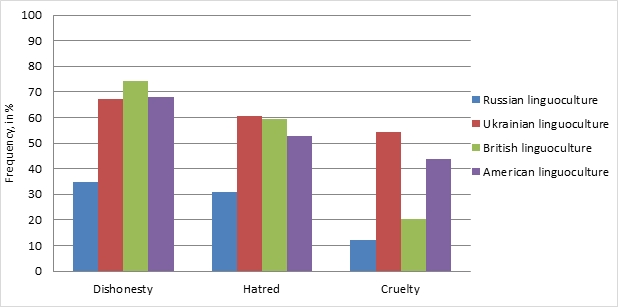

Figure 2. Qualitative representation of the main qualities of a bad person (according to psycholinguistic experiment data)

It is obvious that dishonesty is a strongly pronounced quality of a bad person for the speakers of Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures. Representatives of these linguocultures are also practically in solidarity with regard to hatred as one of the manifestations of a bad person. Cruelty as a negative quality of a person is relevant for Ukrainians and Americans (more than 50% and about 45% of the answers, respectively), while the representatives of the Russian and British linguocultures show, if we may say so, a little more tolerance in relation to cruelty as an unconditional negative quality of a bad person (the range of answers from 10% to 20% respectively).

11. The core of the axiological conceptual opposition between truth and lie in Russian is formed by the following lexemes правда, истина, неправда, ложь; in Ukrainian – правда, істина, неправда, кривда; in English – truth, lie.

The near periphery is occupied by derivatives of the key lexemes: правда (Russian правдивый, правдолюб, оправдать, etc., Ukrainian правдивість, правдивий, правдувати, виправдати, праведний, справедливість, справді, неправда, etc., English truth –true, trueness, truism, truly); ложь (Russian лгать, изолгаться, лгун, ложный), кривда (Ukrainian скривдити).The core zone of these linguomental subspheres in the British and English linguocultures is formed by synonyms: true – exact, accurate, precise, correct, right, etc.; lie – deception, disinformation, distortion, evasion, fabrication, falsehood, fiction, forgery, misrepresentation, perjury, slander, etc.

The far periphery in all the analyzed linguocultures includes figurative components of concepts “truth” and “lie”. This includes metaphorical contexts, paremies, in which associative, connotative meanings of the presented lexemes in Russian, Ukrainian and English are realized.

In the naive linguistic world pictures the truth is associated with honesty (Ukrainian чесність, Russian честность), and the main associations of lie are semantic synonyms: Russian обман, неправда, Ukrainian брехня, English dishonesty, deceit, deception, falsehood.

12. Representations of “friends” and “foes”, which are formed by the culture, have cognitive and affective components. The axiological opposition “friend – foe” is based on numerous criteria and in the closely related and non-closely related linguocultures is correlated with such attributes as “good – bad”, “righteous man – sinner”, “alive – dead”, “like-minded man – opponent”, “related – non-related”.

The linguocognitive structure of subsphere FRIEND consists of “belongingness”, “blood connection” and “spiritual (ideological) unity”.

The near-core elements of the categorical blocks of the axiological subsphere FRIEND in the analyzed linguocultures are the cognitive units “our space”, “our faith” and “our language”, which reflect specific ideas about “our” denotations, formed due to the action of specific cognitive mechanisms, which are topical and communicatively relevant, but have no individual means of objectification, in particular key lexemes, and therefore being representational ones use the connection with the key lexemes of the core segments, in particular with the following lexemes: Russian свой, собственный, родной, Ukrainian свій, власний, рідний, English own, private, individual, native.

The linguocognitive axiological subsphere FOE in the analyzed linguocultures has the following categorical blocks: “territorial non-conformity”, “uncertainty” and “ideological difference”.

The near-core zone of the axiological subsphere under analysis is represented by the linguocognitive blocks “alien property”, “blood unrelatedness”, “alien language” and “a different faith”.

The space “friend/foe” in the naive linguistic world pictures in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures includes several subspaces: personal (“I”), social-personal (“We”), near social (dialogue space) (“You”) and distant social (“He/She/They”) (referent spaces).

Discussion

Modern linguistic research is conducted mainly in two parallel directions: in the mainstream of cognitive linguistics (Divjak et al., 2016; Geeraerts, 1995; Geeraerts & Cuyckens, 2007; Lakoff, 1987; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Langacker , 1990, 2013; Talmy, 2000; etc.) and from the standpoint of cultural linguistics (Huang, 2019; Maslova, 2001; Palmer, 1996; Sharifian, 2011, 2015; etc.), the latter is also known as “linguoculturology” in the East-European linguistic tradition.

Cognitive linguistics addresses the issues related to language functioning not as a special sign system, but as a special cognitive ability of a person to specific linguistic activity, including the ability to repeatedly use a linguistic sign in different functions. Meaning in cognitive linguistics is seen as verbalized knowledge, not as a certain static set of truth conditions, not as a rigid structure of semantic components or differential semantic features, but as an active act of thinking, as a psychological phenomenon, which is a dynamic hierarchy of processes. The issues of studying those mental categories which are not subject to direct observation, which primarily include: initial assumptions, expectations, intentions, knowledge, beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, conclusions, etc., come to the fore.

One of the basic concepts in cognitive linguistics is category, and one of the key phenomena in the description of human cognitive activity is categorization, which is the ability to classify phenomena and distribute them into groups.

The research is aimed at identifying national, peculiar features of this language, because “language is like a sound book, in which all ways of conceptual assimilation of the world by man throughout its history are imprinted. In language finds its expression an infinite variety of conditions in which human knowledge of the world, natural features of the nation, its social structure, historical destinies, life practices were extracted” (Kolshansky, 1990). Yu. Apresyan noticed that “the way of conceptualizing reality (view of the world) inherent in a language is partly universal, partly nationally specific, so that speakers of different languages can see the world slightly differently, through the prism of their languages” (Apresyan, 1995).

It seems obvious that the processes of categorization and conceptualization are the basis of mental activity of human consciousness and are interconnected processes of classification of reality by man. V. Maslova wrote: “both these processes are human classification activity, but with different results and goals: conceptualization is aimed at distinguishing the minimal units of human experience, categorization is aimed at combining the units showing at least partial similarity, into larger classes” (Maslova, 2016). V. Maslova is in tune with E. Ilyinova: “Conceptualization promotes comprehension of all sensations, all the information arriving to the person as a result of work of sense organs, logical and emotional evaluation of this activity. It is directed on allocation of some conditionally limiting units of human experience in their ideal substantial representation (concepts) and by this differs from categorization which is directed on discrete consideration of significant signs and search of similarity between them that allows to establish a system relations uniting units of experience in comparison with the concept accepted as a basis of the category itself” (Ilyinova, 2009).

The relevance of our research presumes that in modern linguistics there has emerged a need to study the peculiarities of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of linguomental phenomena within the framework of comparative cognitive linguoculturology, a new linguistic science. The subject of comparative cognitive linguoculturology is a set of basic oppositions of two or more cultures, archetypal representations, symbolic representations, etc., which are reflected in linguistic units, elements of human language activity, as well as linguistic and speech specificity of these units and elements themselves and cognitive processes of their generation.

It should be admitted, that the aim of comparative cognitive linguoculturology is to reveal and compare general regularities and national-cultural differences of linguomental spheres and subspheres. The comparative cognitive linguoculturology explores both theoretical methods and empirical ones, for example, a psycholinguistic experiment.

As Sergienko N. admitted “if we make the analogy of language with the Universe, national languages represent a great multitude of Galaxies, which have undergone a complex and long way of their formation, development and interaction with each other. Galaxies consist of stars and planets – in the linguistic perspective: linguomental spheres and subspheres. In our study, the object of study was the anthroposphere with its generic, axiological and emotive subspheres. Continuing the astronomical analogy, stars and planets consist of smaller units: living organisms, molecules, atoms. For the researcher of comparative cognitive linguoculturology these are lexical-semantic fields, grammatical structures, phraseological units, texts, discourses, etc.” (Sergienko, 2019).

Conclusions

The comparative analysis of linguomental anthroposphere in Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguocultures reveals more substantial approach than in case of traditional description of the peculiarities of the Russian, Ukrainian and English languages.

Our research focuses on the relationship between language, thought and culture on a practical level, describing the content of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of linguomental anthroposphere on the basis of purely linguistic and experimental methods.

Inter-cultural linguistic study provides a deeper understanding of linguocultures compared to the study of a single linguoculture. Seeking to uncover the peculiarities through linguistic and psycholinguistic methods, the author of the paper constantly resorted to comparisons of closely related and non-closely related linguocultures, which allowed for a more qualitative analysis of each.

In conclusion, let us note that the concept (theory, methodology, procedure) developed in this study of the peculiarities of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of linguomental anthroposphere provides an opportunity to consider a much wider range of linguomental spheres and subspheres, and linguocultures as well, than the limits of this paper allow. In the future it will be interesting to analyze the peculiarities of linguocognitive categorization and conceptualization of such linguomental subspheres in the linguomental anthroposphere as PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY, LIFESTYLE, CREATIVITY, POLITICS etc. on the material of the East Slavic, Germanic, Romanic and other languages and linguocultures within the framework of comparative cognitive linguoculturology.

Reference lists

Agha, A. (2006). Language and Social Relations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Apresyan, Yu. (1995). The image of the human in the language: an attempt of comprehensive description, Topics in the Study of Language, 1, 37-67. (In Russian)

Divjak, D., Levshina, N. and Klavan, J. (2016) Cognitive Linguistics: Looking back, looking forward, Cognitive Linguistics, 27 (4), 447-463. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2016-0095. (In English)

Duranti, A. (1997). Linguistic Anthropology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Geeraerts, D. (1995). Cognitive Linguistics. Handbook of Pragmatics, John Benjamins, Amsterdam, 111-116. (In English)

Geeraerts, D. and Cuyckens, H. (2007). Introducing cognitive linguistics. Oxford handbook of cognitive linguistics, 726-752, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Huang, J. (2019). Cultural Linguistics: Cultural Conceptualisations and language. Intercultural Pragmatics, 16 (5), 619-624. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2019-0031. (In English)

Humboldt, W. (1999). On Language: On the Diversity of Human Language Construction and its Influence on the Mental Development of the Human Species, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Ilyinova, E. (2009). Conceptualization of fiction in the linguistic consciousness and in text, D. Sc. Thesis, Volgograd State Pedagogical University, Volgograd, Russia. (in Russian)

Kolshansky, G. (1990). Ob"ektivnaya kartina mira v poznanii i yazyke [Objective world picture in knowledge and language], Nauka, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Kubryakova, E. S. (2004). Yazyk i znanie. Na puti polucheniya znanii o yazyke. Chasti rechi s kognitivnoi tochki zreniya. Rol' yazyka v poznanii mira [Language and knowledge. On the way of learning about the language: parts of speech from a cognitive point of view. The role of language in the knowledge of the world], Languages of Slavic Cultures, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. What Categories Reveal about the Mind, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. (In English)

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we Live by, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. (In English)

Langacker, R. W. (1990). Concept, Image, and Symbol. The Cognitive Basis of Grammar, Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany. (In English)

Langacker, R. W. (2013). Essentials of cognitive grammar, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Maslova, V. A. (2016). The Russian language through the codes of cultural linguistics, RUDN Journal of Russian and Foreign Languages Research and Teaching, 3, 27-33. (In Russian)

Maslova, V. A. (2019). Linguocultural Introduction to the theory of human, Bulletin of the Moscow State Regional University (Linguistics), 3, 21-28. https://doi.org/10.18384/2310-712X-2019-3-21-28(In Russian)

Maslova, V. (2001). Lingvokul'turologiya [Linguoculturology], Academy, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Palmer, G. B. (1996). Toward a Theory of Cultural Linguistics, University of Texas Press Austin, TX, USA. (In English)

Sergienko, N. A. and Gramma, D. V. (2019). Linguo-mental sub-sphere of sadness in naïve language pictures of the world of representatives of the Russian, Ukrainian, British and American linguo-cultures: results of psycholinguistic experiment, Topical problems of philology and pedagogical linguistics, 1, 77-84. https://doi.org/10.29025/2079–6021-2019-1-77-84(In Russian)

Sergienko, N. A. (2019). Comparative cognitive linguoculturology as a new scientific direction in modern linguistics, Political linguistics, 6 (78), 37-43. https://doi.org/10.26170/pl19-06-04(in Russian)

Sharifian, F. (2011). Cultural Conceptualisations and Language. Theoretical Framework and Applications, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam. The Netherlands. (In English)

Sharifian, F. (2015). Cultural Linguistics and world Englishes, World Englishes, 34 (4),515-532. (In English)

Sorlin, S. and Gardelle, L. (2018). Anthropocentrism, egocentrism and the notion of Animacy Hierarchy, International Journal of Language and Culture, 5 (2),133-162. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijolc.00004.gar(In English)

Sousa, L. P. Q. (2019). Pennycook, A. (2018). Posthumanist applied linguistics. Oxford

and New York: Routledge, Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J.,21(1), 139-142. (In English)

Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a cognitive semantics, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. (In English)

Tyurkan, E. (2015). Holistic Linguistics: Anthropocentric Foundations and the Functional-Cognitive Paradigm, Prague Journal of English Studies, 4 (1), 125-155.https://doi.org/10.1515/pjes-2015-0008(In English)

Wortham, S. (2008). Linguistic Anthropology, available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/162 (Accessed 10 December 2021). (In English)