The world of interpretations in culture space

Abstract

Text interpretation is essentially a dialogical form of knowledge. The sense of a text exists in reality only within human communication, within a situation of a dialogue. Dialogue turns out to be impossible when its participants only consider the interlocutor's messages through their own usual and limited set of senses, or they try to fully perceive the interlocutor’s way of comprehension by tending to break all links with their sociocultural environment’s normative-valued systems. And only partial digression beyond the limits of the conventional enables us to find common ground for understanding. Therefore, understanding always appears not simply as a dialogue, but as a collision of "the usual" and "the unusual". This process is connected with loosening of well-known ideas, taking phenomena out of their comprehension’s familiar context and destructing the old sense. Understanding starts from the initial point in dialogical movement – a given text requiring understanding as a communicative subject. A movement to the past – past contexts, when it is necessary to understand the text the way the author understood it himself without going beyond this understanding. The solution of this hermeneutic issue is rather difficult and requires the involvement of a huge amount of material. And finally, a movement to the future – prescience, construction of further contexts. Senses "flatten" without such a work of understanding. They transform into knowledge and stop dividing (changing). Every author is a prisoner of his epoch, of his contemporaneity. Subsequent times liberate him from this captivity, and literary studies are called upon to assist this liberation. Hence there is a need for the skills of not only understanding, but also explaining and interpreting texts. When we move from understanding a text to interpreting it, we leave the text in its semantic uniqueness and move into the communicative space of semantic transformations.

Introduction

The functions of a dialogue are progressively extending in the modern world. As well as forming new values indirectly, dialogue also becomes a value in itself. A meaningless dialogue is absurd. The culture of mutual understanding presupposes recreation and improvement of mechanisms and technologies of comprehension.

Furthermore, an enormous number of various texts, including fake ones, has fallen down on human memory due to the information revolution. Filtration, processing and assimilation of information prompt a person to come back to the culture of working with a text. Semantic text processing, is the leading component of text analysis, although not the only one. There is another aspect of the relevance of semantic analysis of the text. It involves finding the senses necessary for human life. These senses are the essential characteristic of the texts. While accumulating in culture, they had to be preserved and displayed. Replacing the mythological Hermes, text acts as a mediator, as a subject of communicative act. It contains information not only about events but also about the intention (sense) to transfer this information in a certain period of time or in a specific communicative situation. Learning to understand makes people more comprehensible, and this, in turn, affects both labour productivity and a person's creativity, and even life expectancy.

The scope of research on comprehension, text and meaning has exposed the idea that narrow specialisation was precisely what slowed down the solutions to the problems posed. The basic meaning of the text is referred to as text sense in this article. The text sense interpreting issues turned out to be much more complicated compared to the other tasks solved in certain disciplines, in certain areas and in certain practices. Despite the fact that semantic analysis of the text affiliates to philology, G. O. Vinokur wrote that “the main task of the philologist is to interpret the content and the meaning of the text” (Vinokur, 1991: 81). Text meaning is being discussed within such disciplines as text theory, text linguistics, poetics, analytical rhetoric, pragmatics, semiotics, hermeneutics, pedagogics, speech communication, and also philology which incorporates the canons of human comprehension. These discussions define the multidimensionality of the text (Bloom, 1975; Culler, 2002; Derrida, 1972; Ma and Zalesova, 2012, etc.).

Main part

The widespread notion of understanding as something extremely simple, requiring little thought, is quite common and sometimes the word 'understanding' itself is rarely used in everyday speech to mean 'grasping' or ‘assimilating the meaning of what is said'. Along with this, text is a sociocultural product. Everything is socialized in it: the form (language), the structure (logic), and the designated reality (depicted subject). Sense is a phenomenon of individual consciousness, i.e., a life discourse of a particular individual. At the same time, the individualization of sense-making is not absolute; it cannot, strictly speaking, even be called convincingly dominant. “Sense horizons” as all possible limiting levels of the text content are potentially available to all native speakers, their mentality and value system. Due to this, one can comprehend and assimilate “alien” senses. In other words, an individual can "rediscover" them.

The sense making process is a transcendental process staying beyond the sense horizon of the text. It is characteristic of prophets, geniuses or insane people. For others text understanding is interaction of minds through the text. According to psychologists, sense (personal sense), is the phenomenology of a person’s individuality. Applying to the whole life (life sense) or to its individual sides, senses correlate with the ultimate purposes of existence. And it is connected with the following. Just as thinking works with different logics (formal, dialectical, probabilistic, abductive, symbolic, etc.), so comprehension uses different techniques as “the third part in communication”. “Each dialogue takes place, as it were, against the background of a reciprocal understanding of an invisibly present third person, standing above all participants in the dialogue (partners)” (Bakhtin, 1979: 306).Thus, in relation to the content sense is a meta-level description of the text. This meta-level belongs to comprehension.

In this case, text can be considered as an object, as a subject and as an instrument. Understanding the author's intent (interpretation), textual meaning (making sense of what you have read) and ways of putting it into a different context (interpretation) involve different techniques for working with textual content. “On the one hand, it can be difficult to reveal an author’s intention in the text and, moreover, it is often irrelevant to the interpretation of the text. On the other hand, there is an intention of the exponent who simply “hits the shape of the text which will serve his own purpose” (in the words of Richard Rorty). A third possibility occurs between those two intentions – the intention of the text” (Eco, 1990). Detecting this “intention” means to discover, to understand the sense of the text itself. To discover this "intention" means to reveal, to understand the sense of the text itself – the ultimate goal of the creation and existence of the text, which is not always clear even to its author. Actually, only then can we talk about the author's or the reader's semantic shifts in the understanding of the text.

The sense of the text as a subject of communication is the zero-reference point in the genesis of sense. Text is an imperative as well as the author's voluntaristic project (and the proving ground for the reader's semantic exercises).

Materials and Methods

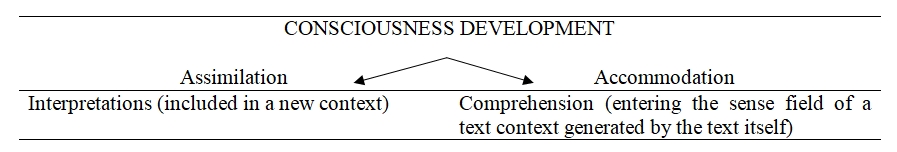

Jean Piaget substantiated such dialecticism arguing about the ways the two complex systems can be balanced with each other. The necessity to comprehend and to integrate new experience leads to restructuring of the internal picture of the world. The pairing of the new with the already established occurs through two opposite, but dialectically related processes: assimilation and accommodation (Piaget, 1954: 352-354). According to J. Piaget, the expansion and complication of connections with the outside world is carried out in a universal way, the same for both biological functioning and the consciousness development.

Referring to a procedure of comprehension of the text we can notice that there are two similar strategies for extracting sense from the text and using the text. Text can be assimilated (included in a new context) as well as accommodated (put into the sense field or a context given by the text itself). In fact, it is referred to appropriation (using “alien” senses) and assimilation (transformation of the original according to internal phenomenology).

Assimilation always involves a constructive effort, and construction is organization. It is the "tightening up" of an event to the pattern of structure available to the individual at the moment. Assimilation involves constructing, and construction is an organization. It means “pulling” events to the pattern of the structure available to an individual has at the moment. As Jean Piaget asserted, assimilation by nature is a conservative process. The main function of this process is to transform the unfamiliar into the familiar, to reduce the new to the old. The result of assimilating processes is the complication and addition of the existing system without changing its essential, constitutive characteristics. This ensures a progressive but smooth nature of the capacity increase, i.e., intellectual development (which was researched by J. Piaget).

Accommodation understood by Jean Piaget as an active creative adaptation to the environment requires internal restructuring. The intellectual adaptation to reality means the construction of this reality. Moreover it should be constructed in terms of some fixed structure available to the subject. Every cognitive action includes both processes. Predominance of one component does not cancel an alternative way of processing new experience. “Cognitive exploration of reality always includes both – assimilation produced by the structure and accommodation of this structure” (Nikitina, 2019: 63).

Figure. Two strategies for extracting meaning from text

It should be noted that the above-mentioned study of two processes of constructing mental experience has something in common with other concepts. Hermeneutic methodologist D. Hirsch considered the art of interpretation and the art of understanding as two different processes. There can be many interpretations but the correct understanding is only one due to the fact that interpretations are based on the interpreter’s terminology and understanding is based on text terminology (Hirsch, 1973).

Alfred Schutz, the representative of the phenomenological philosophical school of H. Husserl, described two types of individual interpretations of new information. He differentiated specific spheres of human experience. Along with everyday life, these are religion, sleep, play, scientific theorization, art work, the world of mental illness, etc. The list (which the author left open) can be also supplemented with such spheres of experience as magic, politics, parascience. Schutz defined these spheres as finite provinces of meaning, rather independent mental representations of specific experience. Direct interaction between these provinces of meanings (the exchange of meanings) is impossible. The meanings of one province are inapplicable for constructing explanatory schemes within the framework of another province. The same facts can act like “signs”, phenomena indicators present in this sphere of reality as well as representatives of other reality – symbols which are not included in the given sphere of experience (Schutz, 1962: 312).

The connection of signs with the signified within a single province of meanings is quite definite. At the same time, symbols representing quasi-reality can reflect multiple and rather arbitrary connections with other spheres of reality. According to Schutz’s logics, we can say that texts can be interpreted as a sign at the first stage of text interpretation. Due to this, texts are identified with a definite sphere of meanings, they are “normalized” (typified), correlated with phenomenology and logics of this sphere. This initial step does not exhaust the possibilities of interpretation. The facts may not fully fit into the explanatory scheme dictated by the logic of a given range of values. For example, they can excessively “stick out” acquiring an inappropriately massive meaning (“Once upon a time there lived a king. And there was a flea with him…”). Or it is impossible to “normalize” them, i.e. explain them exhaustively. Then the process of interpretation moves further to assessing the phenomenon as an indicator of another reality (different system of meanings).

Schutz believed that symbols are communicative means between the realities of the spheres. Thereby, we can try to establish communication with the other sphere of reality. This is the act of metacommunication. “Thus, we can presumably talk about the existence of two types of interpretation – accommodating (detached sphere of experience) and semiotic-assimilating (establishing the interaction between spheres of culture). The first interpretation is characterized by a tendency for unambiguity of the meaning and rejection of other interpretations (references to transcendental spheres). The second one is an attempt at dialogical interactions between different provinces of meaning” (Nikitina, 2013).

Results and Discussion

The procedure of comprehension is triggered by questioning. In order to find answers, we need to be able to ask questions correctly. Linguists get to the content through language, logicians – through concepts, psychologists – through images. But the comprehending person takes a special position between these specialists. He refocuses the sense proceeding from his “non-comprehending” position. After all, the problem of comprehending arises only when it becomes difficult to understand, when there is no understanding at all. The textual tradition where the cognizing subject has rooted, contains both the object of comprehension and its basis: one should understand what one is within from the outset. Unlike linguists, philologists, logicians, or psychologists, the understanding person faces problems of misunderstanding. Here is an example of misunderstanding and reinterpretation of the content of a text from a different cultural context.

“Never talk with teenagers about classical literature. Don’t do it. It can cause a mental trauma. I’ve already got one. Once being on vacation, I relaxed and lost my caution and decided to ask my junior gently about our great classical literature. It started off so lightly, but pretty trivial:

- And what is your favourite heroine in literature?

And he told me on the word, without hesitation:

- The old woman-pawnbroker from "Crime and Punishment".

Me, getting stunned a lot: “Why?!”

With dignity and deep conviction in voice a teenager said:

“You know, Mom, women, as a rule, were far from business in those old days. Moreover, they did not study mathematics and economics properly. This pawnbroker was a very advanced and progressive woman for her time! And mind you, she alimented her pregnant sister Elizabeth! She fended for herself and let others live their lives. And then, you know, some crazy man with an ax jumps out and bang!

One of the most deserving women of that time was killed, immediately excluded from the plot. And so, it would be interesting to read in more details; why she chose such a job, how she did business ... It is much more interesting and useful than reading about the mental anguish of the murderer.

I didn’t ask anything else. I’m too fainthearted” (Nikolaeva, 2017).

M. Bakhtin noted that "in the field of culture, the extrinsic approach is the most powerful lever of understanding. A foreign (alien) culture reveals itself more fully and deeper only in the eyes of another culture (but not in its entirety, because other cultures will come and see and understand even more). One sense reveals its depths meeting and coming into contact with another, alien sense: a kind of dialogue starts between them, which overcomes the isolation and unilateralism of these meanings, these cultures” (Bakhtin, 1979: 334-335). We pose new questions to a foreign culture which it did not pose to itself. We are looking for an answer to this query and a foreign culture responds, revealing its new sides, new semantic depths to us. It’s impossible to understand in a creative way something different and foreign without posing your own (inside) questions (but, of course, these should be serious, original questions). When such a dialogical interaction of two cultures occurs, they do not merge or mix, each retains its unity and open integrity, but they are mutually enriched" (Bakhtin, 1979: 334-335).

The subjective attitude towards the text implies accommodation as an initial step in communication – moving to the position of the text. The attitude towards the text as an object of understanding leads to interpretive techniques, as the text itself becomes merely an element of the receiving context or frame. The subjective attitude to the text presupposes accommodation as a primary level in communication, i.e. transition to the positions of the text. Since the text becomes just an element of the receiving context or frame, the attitude to the text as an object of understanding leads to interpretative techniques. In the first case, the text acts as a subject with gained authority which focuses on understanding. The emphasis therefore is on understanding. Three levels of sense have already been prepared by semiotic organization of the text itself. In the second case, the text leaves its usual habitat. And if it comes to the other habitat where this text can also be reinterpreted according to the logical rules of the receiving sphere, the destiny of “Kolobok” awaits it (Kolobok is a Russian fairy tale the plot of which is very simple. Kolobok is a piece of bread whom every animal (met by Kolobok) threatens to eat). One logic absorbs the other through normalising the situation and bringing it under its own, familiar logic. The bread (Kolobok), even if it talks, must be eaten. As an example of reinterpretation involving different contexts, let’s refer to “Kolobok” itself.

The tale is based on the idea that boasting is not good. The story tells that every cunning one can be tricked out by the more cunning one. Literal explanation is determined by the plot of the fairy tale. We can find this plot in different variations in the folklore with common linguistic and cultural roots (Indo-European). Like any fairy tale, “Kolobok” has considerable potential in the “crystallization” of various meanings immanent in this cultural tradition. As A. S. Pushkin wrote: “Fairy-tales, though far from true, teach good lads a thing or two!” Of the many interpretations of the sense of the tale, here are just two that are indicative of the contexts in which the understanding unfolds.

The first one is archetypal. The archetype of the Hero contains a strict definition of his mission: “The Path of the Hero” full of vicissitudes and trials, leading to victory and gaining a reward. Animal images personify human qualities in metaphorical world. The connotative meaning of these images is presented in the fantasy discourse as follows: a hare means cowardice and lack of integrity; a wolf means cruelty, a bear is a dull force, a fox is cunning and deceit. In this system of semantic reference points “Kolobok” is a metaphorically stated life story of the “last-born child” in a family. There are no prospects in the decayed, decrepit home for him. After all adventures, disappointments and other experiences the protagonist found a new belonging. He was absorbed and integrated by a stronger family line (He simply got married and moved to his wife’s family). Recalling the Gennep’s initiation scheme (Gennep, 2002) its main ritual stages totally correspond to the above-described evolution of Kolobok: separation from the previous community – “non-existence”, symbolic death. And as a result, entering a new community and “rebirth” in a new role, gaining a new status.

Tales about the youngest son reflect the universal principle of hierarchy in a quite developed society. The one who joined the system later than others has less rights. This truth of life is accentuated in fairy tales. We can follow the path of youngest son whose birth was unexpected, “unplanned” (everyone needed is already there). There is no share in common resource for him. Or there can be a scanty, ridiculous part of property like an old cat and worn-out boots. There is no rightful place for the junior in his surrounding, everything is already taken. This theme of deprivation of the younger sounds even harsher in Russian fairy tales. “The elder was a smart fellow. The middle one was neither fish nor flesh. The youngest one was a fool at all”. There is nothing to count on for the youngest in his family. Thus, he is a fool. Further, the path of this completely unheroic “Hero” certainly presupposes finding an external source of strength (the “last-born” is always weak). And this leads to a natural ending – joining a powerful family (“and married to the king’s daughter”). If the way to become a knight is closed, there is always an opportunity to become a usurer (Slabinskii, 2012).

The second interpretation of the tale is sacral (reference to religious province of meanings; in this case – a context of Slavs’ pagan religious beliefs).

All characters here are considered as symbols representing the sacred reality in the tale’s content initially identified as an “everyday” one. The Slavic myth about the creation of a man says that life appeared as a result of energy merging of Kin (creative, “created” inception) and Mother Earth. Recognizable as figures familiar to everyone from the sphere of everyday reality (elderly spouses), the characters of the beginning of the tale can also be considered (at the next level of interpretation) as symbols – metaphorical images of the Kin and Mother Earth (very old – a metaphorical indication of the eternal). The further development of the plot also corresponds to the sacred scheme: the Old Man (Kin) initiates the appearance of Kolobok (he puts the energy into “starting” the process of creation and asks to bake Kolobok). The Kin has the energy but he does not have any resources or materials. And Mother Earth has this resource and owns all the fruits (parts) of her own. The process of searching for a sufficient number of products (flour as ground grain) begins with collecting the flour remnants in “barns and hoppers” for mixing the dough and ("to bungle" according to the expression of the ancient Slavs), i.e. to please the Sky (God). It means to give not only a body but also a soul. According to beliefs of ancient Slavs the soul is manifested through a given name. “Kolo” means a circle, a circle of life, a symbol of eternity of soul (symbol within a symbol is a frequent example of metacommunication in sense-making process). Ancient Slavic mythological symbolism can be traced in this fairy tale which builds the semantic bridges to other, related mythological constructions. In particular, to the myth of mysterious, incomprehensible Russian (Slavic) soul. In this sense, a “children's” fairy tale appears in its traditional moral didactic role: a hint is a lesson. To protect oneself and to adapt skillfully are out of the Slavs’ moral virtues. The same refers to greed, and cruelty, and desire to be “the great one” (power and mightiness). Therefore, the characters personifying the above-said – the Hare, the Wolf and the Bear– did not become a serious obstacle on Kolobok’s way. But meeting the Fox turned out to be fatal.

The openness and trustfulness (“simplicity of the soul”) inherent in the “Slavic soul” are defenseless against cunning and guile. Russian history has confirmed this fact many times. Wise ancestors’ message is to learn to recognize treachery and lies, but not to go to the other extreme of suspecting everyone everywhere. This gave rise to an aura of mystery of the Slavic soul – often a “meaningless and merciless” total protest against everything and everyone. Searching for the balance between reckless trust and total denial is a message left by Slavic ancestors to their descendants' generations.

Concluding a short excursion into the semantic potential of fairy tales, let us ask ourselves a question. Why a fairy tale “for the little ones” contains such a global and significant meaning (in fact, the secret of nation's viability. Children do not yet have sufficient social experience, logical maturity of consciousness. But child's consciousness has its own considerable capabilities which are mainly lost while saving up life experience. Information presented in a figurative form accessible to the child's psyche is assimilated without any cognitive distortions and subjective “modifications”. And it is fixed there as the basis of knowledge about life. We remember: what comes first does always have more influence and rights. And this proper knowledge about life is activated in critical (extremely critical) situations. And there are plenty of such cases in the history of the country. Though, the path from the truths, hidden in the most archaic layers of consciousness, to the particularity of conscious decisions is unobvious and tortuous, it certainly exists and it is actualized at the moment of a fateful choice.

Interpretation of senses cannot be attributed to a strictly scientific procedure. Sergei Averintsev asserted that there are two levels clearly distinguished within the analysis of a text: the description of the text and the interpretation of different layers of its symbolism. Basically, description should tend to consistent "formalization" as in exact sciences. On the contrary, the symbolic interpretation is precisely the element of humanity within humanities in the direct sense. In other words, it is a question about the humanity, which is not materialized but symbolically realized in material. It is a firmly “extrascientific form of knowledge that has its own internal rules and criteria of accuracy” (Averintsev, 2001: 157-158).

There is a third possible variant of interpretations. This is a variant of intercommunication of two logics (or more) from two spheres of culture. It is the case of the dialogue of two different senses tending to merge into a third, additional logic. The metalogic of interpretations which can be specified as dialogics. This field is still marginal but creative.

Conclusion

There are two similar strategies for extracting sense from the text and using the text.

The first task of understanding is penetration, accommodation to the text, comprehension and evaluation of what is closer to the present moment. The second task is to be included in a context foreign to the author using temporal or cultural outsideness as human experience acquires sense only when it is included in a certain tradition. Cognition begins with a premise. This premise is a result of “normalizability” of the text to a certain province of meanings (typological identification of the text) and with the “standard” traditional interpretation by default pre-reason – “vorurteil” (Gadamer,1999). The reduction of the stage of preliminary “template” understanding and the avoidance of understanding in a particular way deprive the understanding process of the most important orienting “tuning” link. This action leads to problematic cognition (misunderstanding). Interpretation of the text is one of the forms of existence of knowledge: dialogical. The sense of a text does really exist only within the exchange of axiological worlds, within situation of a dialogue.

Dialogue turns out to be impossible where the speech of participant is added to familiar and fixed set of senses. Or when one of the participants of a dialogue tries to fully perceive the way of comprehending suggested by the interlocutor. It becomes possible only with complete rejection of the sense-making references inherent in one’s own sociocultural tradition (which is unreachable as long as a person's consciousness is functioning). Partial, local admission of alternative, primarily foreign, senses to one's own semantic system allows one to create a basis for understanding (the applicability of new senses in one's own world cognition).

Such a transcendence of sense logics always presupposes the unity of multidirectional procedures. On the one hand, it reveals the unexpected, strange in comparison, different from traditional schemes of comprehension and ratings one. On the other hand, it brings the unknown, the unusual into compliance with the familiar, the well-known. Therefore, understanding as a dialogical form is always revealed in collision and further interaction of “the new” and “the familiar”. The result of such a collision is the inevitable restructuring of existing ideas, the removal of a subject of comprehension from the familiar context of comprehension, the transformation of sense. This is the aspect of sense-making process which V. B. Shklovsky (1925) successfully called “defamiliarisation”. As a secondary process every comprehension is basically unfolding as rethinking, creating a new semantic chain of “detached” senses.

In dialogical movement the initial point of comprehension is a given text that requires understanding as communicative subject. It is a movement to the past contexts, when we need to understand the text according to the author’s conception not going beyond the limits of his idea. The solution of this hermeneutic task is rather difficult and requires the involvement of a huge amount of material. And finally, it presupposes the movement into the future – forestalling, construction of further contexts. Without such comprehension activity the senses “compress themselves” transforming into the knowledge and stop dividing (changing). Every author is a prisoner of his epoch, of his contemporaneity. Future times release him from this captivity. And literary studies are meant to help this liberation. Hence there is the need for the skills of not only in comprehension, but also in interpretation of texts. Moving from comprehension to interpretation of the text, we leave the text in its semantic uniqueness and shift into the communicative space of semantic transformations.

The text, as an instrument of influence, as a subject of quotation, imitation, etc., becomes a part of innumerable semantic divisions. A comprehending individual can enter a reflective stance in his comprehension through the gap between the content and the sense of the text. Self-perception guides a person to study the procedures of comprehending. The ability to separate, construct, change contexts of semantic analysis of the text is the topic of future interventions in the field of sense.

Reference lists

Averintsev, S. S. (2001). Simvol khudozhestvenny [Symbol artistic], in Averintseva, N. P. and Sigov, K., B. (eds.), Sofiya-Logos.Slovar', DukhiLitera, Kyiv, Ukraine. (In Russian)

Bakhtin, M. M. (1979). Estetika slovesnogo tvorchestva [The aesthetics of verbal creativity], Iskusstvo, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Bloom, H. A. (1975). Map of Misreading, Oxford University Press, New York, USA. (In English)

Culler, J. (2002).The Pursuit of Signs: Semiotics, Literature, Deconstruction, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, USA. (In English)

Derrida, J. (1972). Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences, in Macksey, R. and Donato, E. (eds.), The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, USA, 247-272. (In English)

Eco, U. (1990). Interpretation and Overinterpretation: World, History, Texts [Online], available at: https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_resources/documents/a-to-z/e/Eco_91.pdf (Accessed 8 August 2022). (In English)

Gadamer, H.-G. (1999). Tekst i interpretatsiya (Perevod Anan'eva E. M.), in Shtegmajer, V., Frank, H. and Markov, B. (eds.), Germenevtika i dekonstruktsija [Hermeneutics and deconstruction], Saint Petersburg, Russia. (In Russian)

Gennep, A. van.(2002). Obrjady perekhoda. Sistematicheskoe izuchenie obrjadov [Rites of passage. Systematic study of rituals], Izdatel'skaya firma "Vostochnaya literatura" RAN, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Hirsch, E. D. (1973). Validity in Interpretation, Yale University Press, New Haven, Mass. USA. (In English)

Ma, T. Yu. and Zalesova, N. M. (2012). Interpretatsiya teksta [Text interpretation], Izd-vo AMGU, Blagoveshchensk, Russia. (In Russian)

Nikitina, E. S. (2013). Tipy interpretatsii. Psikhosemioticheskiipodkhod k smysluteksta [Types of interpretation. Psychosemiotic approach to the sense of the text], Mir lingvistiki i kommunikacii: elektronnyj nauchnyj zhurnal, 2 (31). (In Russian)

Nikitina, E. S. (2019). Smyslovoy analiz teksta: A Psikhosemioticheskij podkhod. [Semantic Analysis of the Text: Psychosemiotic Approach.], Leland, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Nikolaeva, A. V. (2017). The blog in a social networking service LiveJournal [Online], available at: https://nikolaeva.livejournal.com/html (Accessed 3 February 2021). (In Russian)

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child, Basic Books, New York, USA. (In English)

Schutz, A. (1962). Collected Papers I: The Problem of Social Reality, Martinus Nijhoff, Hague, Netherlands. (In English)

Shklovsky, V. B. (1925). O teorii prozy [On the theory of prose], Krug, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Slabinskii, V. Yu. (2012). Harakter rebenka. Diagnostika, formirovanie, metody korrektsii [The character of the child. Diagnostics, formation, methods of correction], Nauka i Tekhnika, Saint Petersburg, Russia. (In Russian)

Vinokur, G. O. (1991). O yazyke khudozhestvennoy literatury [About the language of fiction], Vysshaya shkola, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)