Range of associations to Russian abstract and concrete nouns

Abstract

The article deals with the specificity of associations to nouns with a high degree of abstractness and concreteness. Nouns were selected from the created database of abstractness/concreteness ratings of the Russian language; associations were selected from the Russian associative dictionary of Yu.N. Karaulov. The research shows that firstly, verbal associations are one of the main mechanisms involved in language processing, and secondly, abstractness/concreteness plays a key role in generating associations. The paper provides a statistical analysis of 20-25 associations to 50 abstract and 50 concrete nouns, 10 most frequent associations to each word were analyzed in detail and classified into groups according to the type of relations with stimulus words, also each of the selected associations was analyzed for abstractness/concreteness degree using the created database, which allowed making important conclusions about the nature of the context in which the abstract and concrete lexemes occur. The analysis performed in the work allows to reveal the specificity of abstract and concrete nouns in terms of semantic structure of words, to reveal the facts of intersection of concrete and abstract meanings in the structure of the studied lexemes. Moreover, the study makes it possible to test the psycholinguistic theory of context availability on the material of the Russian language by statistical methods. The conclusions presented in the work, based on the linguistic material, correlate with the studies, in which neurobiological mechanisms of perception of concrete and abstract words are studied.

Introduction

It is hard to overestimate the significance of characterizing words by abstractness/ abstractness/concreteness. Literature review indicates a wide range of topics related to the category of abstractness/concreteness. For instance, differences in processing concrete and abstract words by dextro- or sinistrocerebral people are studied in (Oliveira et al., 2013); word concreteness effect types are analyzed in (Mate et al., 2012; Nishiyama, 2013); the question of how concrete and abstract concepts are kept in and retrieved from the long-term memory in (Hanley et al., 2013; Kousta et al., 2011; Paivio, 2013); and there are studies aimed at revealing potential differences in comprehending concrete and abstract words by patients suffering from neuropsychiatric diseases (Loiselle et al., 2012). However, implementation of similar research needs accurate objectified criteria of whether a word is abstract or concrete. For this purpose, researchers of different languages compile databases with ratings of abstractness/concreteness. The core idea of such projects is to assess the characteristics of a word and obtain a numerical indicator of its degree of abstractness/concreteness.

Abstractness/concreteness ratings were explored and validated for a range of languages, such as English (Brysbaert et al., 2014), Dutch (Brysbaert et al., 2014b), Chinese (Xu et al., 2020), etc. The modern database of abstractness/concreteness rating for the Russian language contains 1.5 thousand words (Solovyev et al., 2019a; Zhuravkina et al., 2020; Volskaya et al., 2020). It was collected based on the methodology employed in developing a similar resource for the English language (Brysbaert et al., 2014a).

The database compiled provides objective numeric ratings of abstract and concrete words, it enables to conduct linguistic studies, including transitivity inside lexical-grammatical classes of nouns in Russian or contrasting semantic structures of abstract and concrete words. Other areas where this type of data could be of use are cognitive and neuroscience. For instance, abstract words data are essential in therapy of patients with aphasia (Bailey et al., 2020). Abstractness is also viewed as a text complexity predictor (Sadoski, 2001; McNamara et al., 2014; Solovyev et al., 2019, Solovyev et al., 2020).

Main section

Purpose statement

In this paper, we focus on the range of semantic associations of the abstract and concrete nouns retrieved from the authors’ database. In associative dictionaries each entry as a stimulus is provided with associations which may be organized as an associative field. For this research we used the Russian Associative Dictionary (RAD) by Yu. N. Karaulov as a source of associative fields of concrete and abstract words. We proceed from the view established in psychology and cognitive sciences that mental representations of concrete and abstract words are of different nature, it is especially true regarding associations. We aim at obtaining quantitative parameters and reveal qualitative differences in associations of nouns of two lexical-grammatical classes (LGC), i.e. abstract and concrete nouns. Firstly, the analyses will reveal specific features of abstract and concrete nouns in terms of their semantic structures in paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations; and secondly, identify overlapping concreate and abstract values within the structure of the lexical items under study. Moreover, using Russian dataset and rigorous statistical methods, the research may confirm or refute the psycholinguistic context availability theory presented in the section below.

Literature review

The modern paradigm of abstractness/concreteness studies is equipped with quantitative ratings of abstract and concrete words for English (Brysbaert et al., 2014), Dutch (Brysbaert et al., 2014b), Chinese (Xu et al., 2020), and some other languages.

One of the first rating databases was validated in 1981. In 1966-1968, first O. Spreen and R. W. Schulz (Spreen et al., 1966) and later on – A. Paivio (Paivio, 1986) – collected the data, i.e. 4 292 words for MRC database (Coltheart, 1981). Many researchers use MRC database as the source for their studies (Schock et al., 2012). At present researchers also use neural networks for compiling similar dictionaries (Ivanov et al., 2022).

Defining degree of abstractness/concreteness of a Russian noun implies identifying and considering its semantic and grammatical features. Since the abstractness/concreteness rating database was created based on the idea of fuzzy boundaries separating LGCs of nouns, their numerical abstractness/concreteness indicators reflect the above features. The latter enables considering class-overlapping cases, it is especially significant regarding the class of abstract nouns, since our dataset lacks a noun with the highest abstractness indicator. It implies that semantic structures of all abstract nouns (herein AN) contain at least one component (a seme), which indicates the relation of the abstract word to a concrete referent. At the same time, we do not observe any similar pattern with concrete nouns (herein CNs). We also have to note that, firstly, there are more CNs than ANs in the database. Secondly, there are more CNs assessed with the extreme values.

As for possible techniques to identify concrete components in the structure of an abstract noun, they are quite few. The technique we employ in our research is inventory of associations registered in the dictionary. Moreover, it is our hypothesis that inventory of associations of both classes, i.e. concrete and abstract, may highlight specific features of both abstract and concrete lexical units.

It should be noted that researchers repeatedly addressed associative fields for ratios of frequent and rare syntagmatic and paradigmatic responses (Goldin, 2008). Nouns play a significant role in the structure of associative networks, and that is statistically confirmed. Words of this class are leaders in forming network nodes, as they have no limitations on associations (Shaposhnikova, 2022: 278). According to V. V. Vinogradov, the source of the meaning enrichment of a word is communications where “a single form of a word acquires new meanings and senses” (Vinogradov, 2001: 17).

Research into associative fields also enables to consider how words are represented and organized in the mental lexicon of native speakers (Planchuelo et al., 2022). In this paper, we emphasize the key role of category of abstractness/concreteness in associations formation and its effect on word characteristics. Understanding how words are coded in mental lexicon and interrelate with each other is viewed as important for studying the processes of human cognition (Chen et al., 2014; Lupyan et al., 2020).

An important aspect in these studies is the so-called “concreteness effect” identified in numerous studies. The term is related to the hypothesis that concrete words are easier to memorize and process (Schwanenflugel et al., 1992, Mestres-Missé et al., 2014), it is easier to define them in dictionaries (Sadoski et al., 1997), and concrete words elicit more associations (de Groot, 1989).

One of the proposed theories that allows explaining “concreteness effect” is the Context Availability Theory (CAT) (Schwanenflugel, 1998), according to which concrete and abstract words have different numbers of associations. Concrete words have stronger associative links to fewer contexts, while abstract words, on the contrary, have weaker associative links to more contexts.

Modern studies confirm certain concepts of the Context Availability Theory. For instance, Naumann et al. (2018) argue that abstract words contexts are more difficult to select than for concrete ones. Research also shows that concrete words occur in a few specific contexts, while abstract words are found in a wider and more general context (Hill et al., 2014; Hoffman et al., 2013).

The Context Availability Theory is used as a foundation for studies on the nature of the contexts in which abstract and concrete words occur. According to (Barsalou et al., 2005), both abstract and concrete words basically appear in a concrete context, i.e. in contexts that primarily consist of concrete words. However, some studies show that concrete words are usually found in a concrete context, while abstract ones are found in an abstract context (Frassinelli et al., 2017).

The Context Availability Theory also suggests that associations with words may be used as a research tool in studies aimed at identifying the structure of human lexicons (De Deyne et al., 2015). For purposes of such studies, researchers compile rich databases comprising associations of numerous words (De Deyne et al., 2019). Some research findings indicate that the mechanism of generating associations is a core in the process of separating concrete and abstract words (Crutch et al., 2005; Crutch et al., 2011). The research suggests that there are different organizational systems for concreate and abstract words in human minds: concrete words are grouped in semantic or frame networks, while abstract words are grouped in networks of word associations (Crutch et al., 2005; Crutch et al., 2011; Duñabeitia et al., 2009). Thus, word associations may be not just a paradigm used to study language processing, but its core mechanism (Planchuelo et al., 2022).

Materials and methods

The primary research materials are lexical units with a high-level of abstractness/concreteness, selected from the database created, and associations with those units, selected from Yu. N. Karaulov’s Russian Associative Dictionary or RAD[1].

RAD was created based on the material of a mass experiment conducted from October, 1988 through May, 1990. Each respondent was provided with a questionnaire of 100 stimulus words. Following the instruction, informants were to generate one association per each stimulus within 7-10 minutes (Karaulov, 1994: 191). In total, RAD contains 6624 stimuli belonging to various parts of speech.

An entry to each stimulus was sorted by decreasing the number of cases and comprises responses (associations) arranged in the descending order. Each response is provided with a number specifying the quantity of respondents that generated this particular association to the stimulus word. In the end of the entry, delimiter “+” separates four numbers, the first of which specifies the number of informants that assessed this stimulus in the questionnaire; the second one specifies the total amount of different responses to the stimulus; the third one registers the number of informants that left this stimulus without a response; and the fourth one shows the number of single responses (Karaulov, 1994: 192).

RAD was selected as the main source for the study based on its size: compared to other associative dictionaries of the Russian language, it offers more numerous stimuli. "Slavic Associative Dictionary" 2004[2] is based on 112 mutually equivalent stimuli in Belarusian, Bulgarian, Russian, Ukrainian and Serbian. «Russian associative dictionary: associative reactions of schoolchildren of I – XI classes» edited by V. E. Goldin 2011[3] offers 1126 stimuli.

The methods of creating the database of abstract and concrete units of the Russian language were developed based on the practices of compiling similar resources for the English language (Brysbaert et al., 2014a).

Stimuli were selected based on their frequency from the dictionary by O. N. Lyashevskaya and S. A. Sharov[4], while numeric ratings of abstractness/concreteness were obtained based on a survey of Russian native speakers. For the first thousand words, ratings were obtained through survey of students of Kazan Federal University, Russia (Solovyev et al., 2019a), and Belarusian State Pedagogical University (Zhuravkina et al., 2020). In total, over 700 informants participated in the survey. Associations of the next 500 words were collected on the crowdsourcing platform Yandex.Toloka (Solovyev et al., 2022): they were generated by 600 participants who received instructions and lists of 50 words to respond to.

In both experiments informants assessed concreteness/abstractness of words by a Likert scale from 1 through 5, in which the values of 1 and 5 indicate the concreteness and abstractness, respectively, while 3 indicates that the word may be assessed as both concrete and abstract. Words assessed as 5-3.5 were interpreted as highly abstract; words assessed as 3.4-2.5 were interpreted as words with semantics of both, abstractness and concreteness, while 2.4-1 are viewed as indices of highly concrete words. We also developed and employed numerous quality control criteria as an ‘inclusion filter’ into the database. All the responses that did not meet the criteria were rejected. Thus, within the framework of this study, we selected 50 most abstract nouns with the rating of 3.8-4.5 and 50 most concrete nouns with the rating of 1-1.4.

On Stage 1, about 20-25 associations were selected from RAD for the nouns under study. We did not consider every single response; however, the selected associative row has some single responses in its end. Based on the material above, we performed the quantitative analysis of various single and strong responses to the stimulus words selected from the database.

On Stage 2, we selected 10 associations with each noun. These associative fields include the associative kernel that contains the strongest responses and periphery. Based on the materials above, associations undergo quantitative and qualitative analyses and were classified into five groups, depending on the type of the responses identified.

On Stage 3, all associates in the database were examined for their concreteness/abstractness ratings, and we also analyzed the types of relations of abstract and concrete stimulus words developed. We were mostly interested in associations of the opposite to the stimuli group.

The number of responses to each noun ranges from 0 to 100. However, in RAD, most entries contain about 500 responses. As specified by the authors of RAD, about 100 responses are added to about 1/3 entries, since a limited number of words was listed at the first stage of the experiment, some words were assessed by a smaller number of people, i.e about 100.

Results and discussion

Thus, first, we selected 20-25 associations to each of 50 most abstract words and 50 most concrete words of the database. The most frequent associations and information from RAD for highly concrete words are provided in Appendix 1, while Appendix 2 comprises the same information for highly abstract words. It is believed that the semantic load of abstract nouns is more diverse, as compared to the values of concrete nouns; therefore, abstract vocabulary can evoke more associations and images (Borghi et al., 2017). In this regard, it can be expected that the number of single and diverse associations with abstract nouns is higher than that with concrete nouns.

For abstract nouns, various associations are given within the range of 44-85 in RAD. The arithmetic mean of all similar responses is 67.26. For concrete nouns, various responses are given within the range of 39-68. Their arithmetic mean is 55.58.

The number of single associations with abstract nouns ranges within 27-73. Their arithmetic mean is 52.22. For concrete nouns, the values are 24-57 and 40.12, respectively.

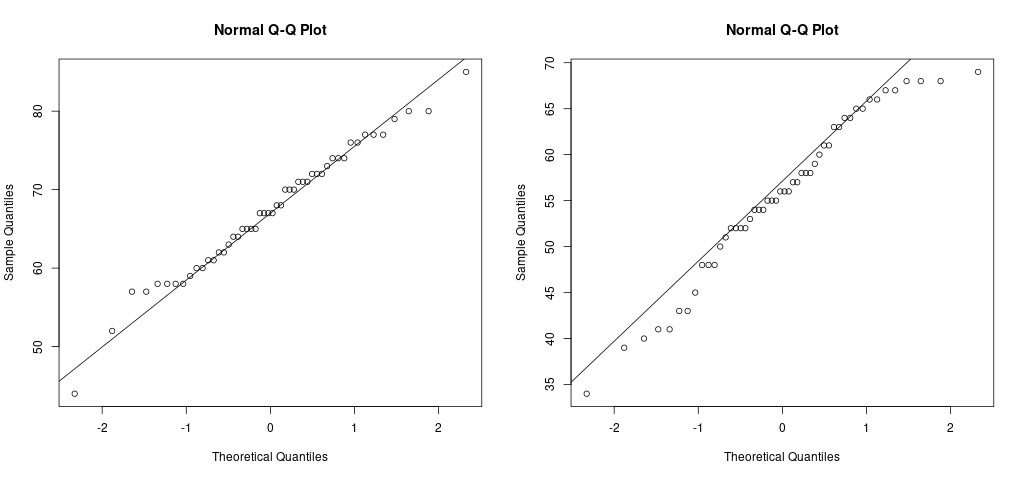

To assess the differences in the indicators considered, we used the Student’s two-sample test. With a two-sided alternative hypothesis, we obtain p = 4.948e-10, which suggests a statistically significant difference in the number of associations, in both cases. It is quite conceivable to use this criterion, since the data demonstrate normality (Fig. 1), which can be seen in quantile plots. In both pictures, points are lined up.

Figure 1. Quantile plots of the numbers of associations for abstract (left) and concrete (right) words

Рисунок 1. Квантильные графики количества ассоциаций для абстрактных (слева) и конкретных слов (справа)

Thus, this difference enables to confirm the hypothesis above regarding the nature of associations with abstract units.

Concrete nouns are expected to have stronger associations than abstract ones, as they refer to really existing objects, which are available for perception. Indeed, the number of strong associations with ANs ranges within 4-22. Arithmetic mean is 10.22. The number of strong associations with CNs ranges within 6-36; however, their arithmetic mean is 15.5.

The Student’s two-sample test with p = 3.564e-05 suggest a statistically significant difference in the numbers of strong associations with abstract and concrete nouns.

We also selected 10 associations with each noun. The associations were classified in five groups, based on the relations found between associates and stimulus words.

I. Paradigmatic Relations

1. Synonym / Context Synonym Associations

Most synonym associations are included in the Dictionary of Russian Synonyms and Semantically Similar Expressions edited by N. Abramov[5]. However, contextual or nonce synonyms are found in this group, too. For instance, it is necessary for the stimulus necessity. There are also synonyms for stimuli homonyms. For instance, icon for the stimulus image or planet for the stimulus world[6].

2. Antonym / Context Antonym Associations

Associations of this group may be exemplified by the following responses: failure for the stimulus luck, distrust for confidence, hatred for love, disrespect for respect, etc.

3. Hyponym/Hypernym Associations

The following responses may exemplify this type of associations: hyponym Christianity for the stimulus religion, hypernym clothes for shirt, hyponyms refined and sand for sugar, etc.

Note that, in some cases, adjective associations from the group of syntagmatic relations overlap this group. For instance, responses wind, philharmonic, or chamber[7] for the stimulus orchestra.

II. Syntagmatic Relations

1. Adjective/Participle/Adverb Associations

These associations were separated from the group of associations as parts of phrases, since it was important for us to trace changes in the descriptive characteristics for AN and CN. For instance, responses, such as rich, rampant, violent, and limitless, for the stimulus imagination; or white, new, silky, flannelette, and blue for the stimulus shirt, etc.

2. Associations that are Parts of Phrases / Set Phrases

This group comprises associations as parts of frequency phrases denoting typical situations, as well as associations as parts of set phrases (phraseological units). In Russian, these associates are usually expressed by verbs and nouns. Examples of associations as parts of frequency phrases are as follows: in business as a response for luck or of a man as a response for ideal. There are instances of associations as parts of set phrases: have a good deal of for the stimulus luck, money for the stimulus time, the last thing to die for hope, etc.

3. Associations that are Potential Parts of Phrases / Set Phrases

This group usually includes noun responses that are or could be parts of phrases or set phrases. For example, will for the stimulus freedom (freedom of will), or faith for hope (faith, hope, and charity).

4. Secondary Associations as Parts of a Potential Phrase

This group consists of secondary associations. In this case, respondents gave an association with the primary response, i.e., the presupposition. Schematically, this associative row can be represented as follows: S – R1 (?)– R2, where S is stimulus, R1 is the omitted response, and R2 is the final response. At the same time, the phrase part is a presupposition. For instance, this group included association TV set with the unit time. Using this association, presupposition newscast can be restored, as a part of the phrase of the Vremya (russ. for time) Newscast. Thus, association TV set is secondary towards the unit time and primary towards the phrase Vremya Newscast.

5. Proper Name Associations

Lists of proper name associations include anthroponyms, toponyms, and nomenclatures. This type of associations was separated from the general group of Syntagmatic Relations, since all associations of the kind are parts of assumptive phrases. For instance, response of Lenin for the stimulus ideal, of Pushkin for the stimulus creation, Entuziastov[8] for the stimulus highway, etc.

6. Evaluations

Evaluations may be exemplified by the following associations: Responses, such as bad, terrifying, or difficult, for the stimulus loneliness, response bad for the unit sin, response disgusting for the unit cognac, etc.

III. Epidigmatic Relations

Derivate / Cognate Associations

This group consists of associations that are stimuli derivatives. For instance, give confidence for the stimulus confidence, or lonely for the stimulus loneliness.

IV. Thematically Related Words or Parts of Frame

This group comprises associations that demonstrate parts of a frame or a group of words thematically close to the stimulus.

This group was not included into the groups of paradigmatic or syntagmatic relations, since here we identify a thematic field (frame) connected with two set of associations: (1) based on paradigmatic relations, but are not synonyms; (2) a potential core of a phrases, but without an explicit link to the stimulus. In this regard, the authors of the dictionary point out: “A frame represents a mental structure similar to pictures and “images”. It acquires signs of typical, familiar situations, which are explicated with an expressive word or a phrase that enable the listener (or an analyst) to “complete” the situation and restore the missing network nodes (Karaulov 1994).

Associations identified by their thematic similarity to the stimulus also possess stimulus-related components in the semantic structures. It is often difficult to separate these units from a group of synonyms, because some of them can be a nonce word and express respondents’ subjective assessment caused by their linguistic and life experience. However, it should be noted and it was mentioned above (cf. description of synonyms), that our classification of words into two groups is based on the dictionary of synonyms ed. by N. Abramov. Examples of associations relating to thematically similar words, are the following responses:

- Responses fear and grieve for the stimulus desperation;

- Responses sorrow, sadness, mourning, boredom, and fear for the unit loneliness; and

- Responses honor, power, and glory for pride, etc.

Associations that are parts of a frame may be exemplified by the following responses:

- Responses artist and painting for art;

- Responses church, God, spirituality, and priest for religion; and

- Responses besom, wash, heat, steam, and sweating room for bath, etc.

V. Phonetically Similar Words

This group includes responses that sound similarly to the stimulus. For instance, dushka (my pretty) to the stimulus podushka (pillow) or zaklepka (rivet) to the stimulus klepka (stave).

Hence, we counted the total quantity of all the given associations for ANs and CNs in each group of our classification. Then we counted the number of words, which generated lexical associations from different groups. And finally, we counted the number of the strongest associations in each group. The findings are presented in Tables 1, 2 below.

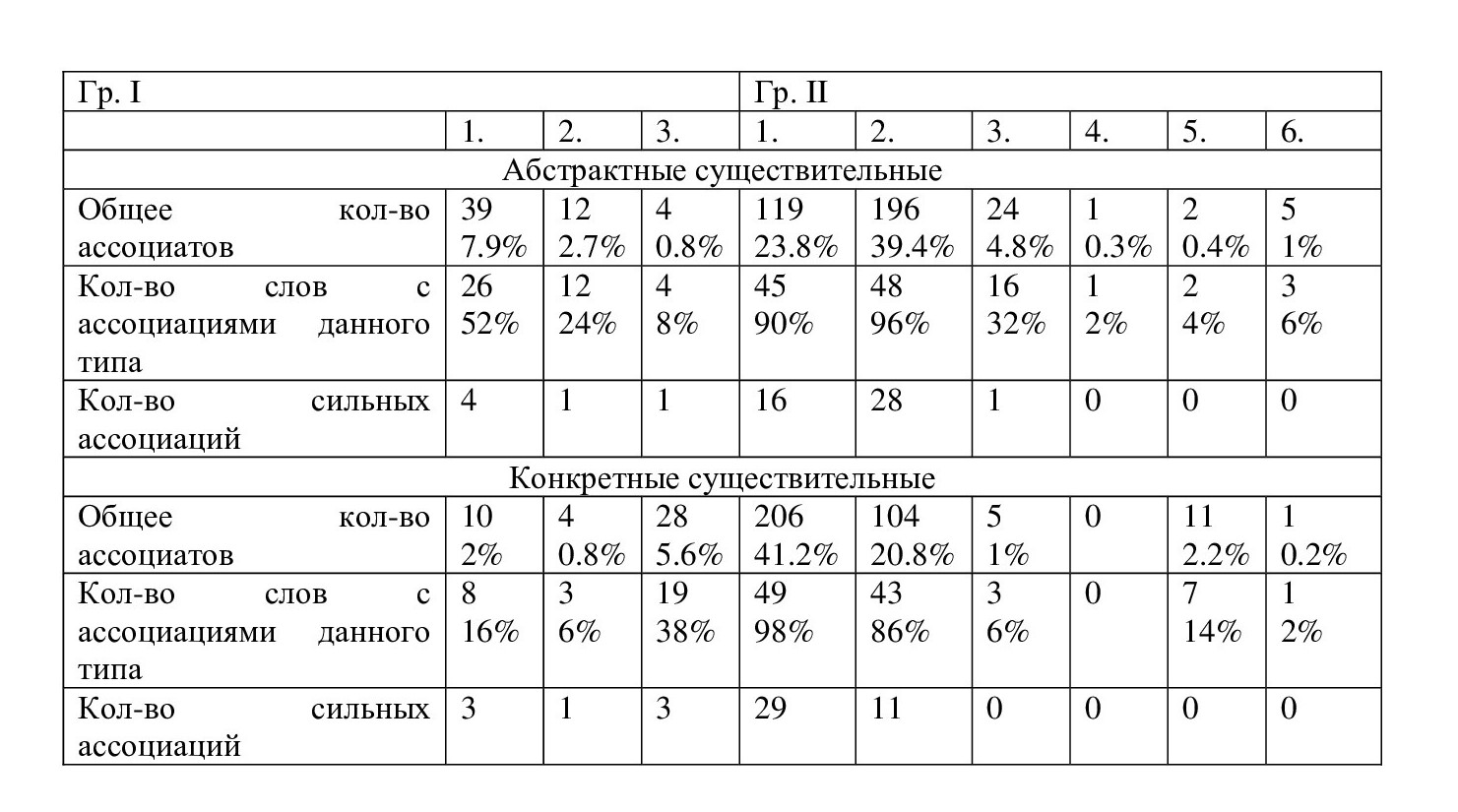

Table 1. Quantitative characteristics of associations with ANs and CNs from Groups 1 and 2

Таблица 1. Количественная характеристика ассоциаций из группы I и II к АС и КС

In Table 1, Gr. 1 comprises the group of associations that form paradigmatic relations to the stimulus word: 1. Synonym / context synonym associations; 2. Antonym / context antonym associations; and 3. Hyponym/hypernym associations. In Table 2, Gr. 2 consists of associations that form syntagmatic relations to the stimulus word: 1. Adjective/participle/adverb associations; 2. Associations as parts of phrases / set phrases; 3. Associations as potential parts of phrases / set phrases; 4. Secondary associations of a potential phrase; 5. Proper name associations; and 6. Evaluation associations.

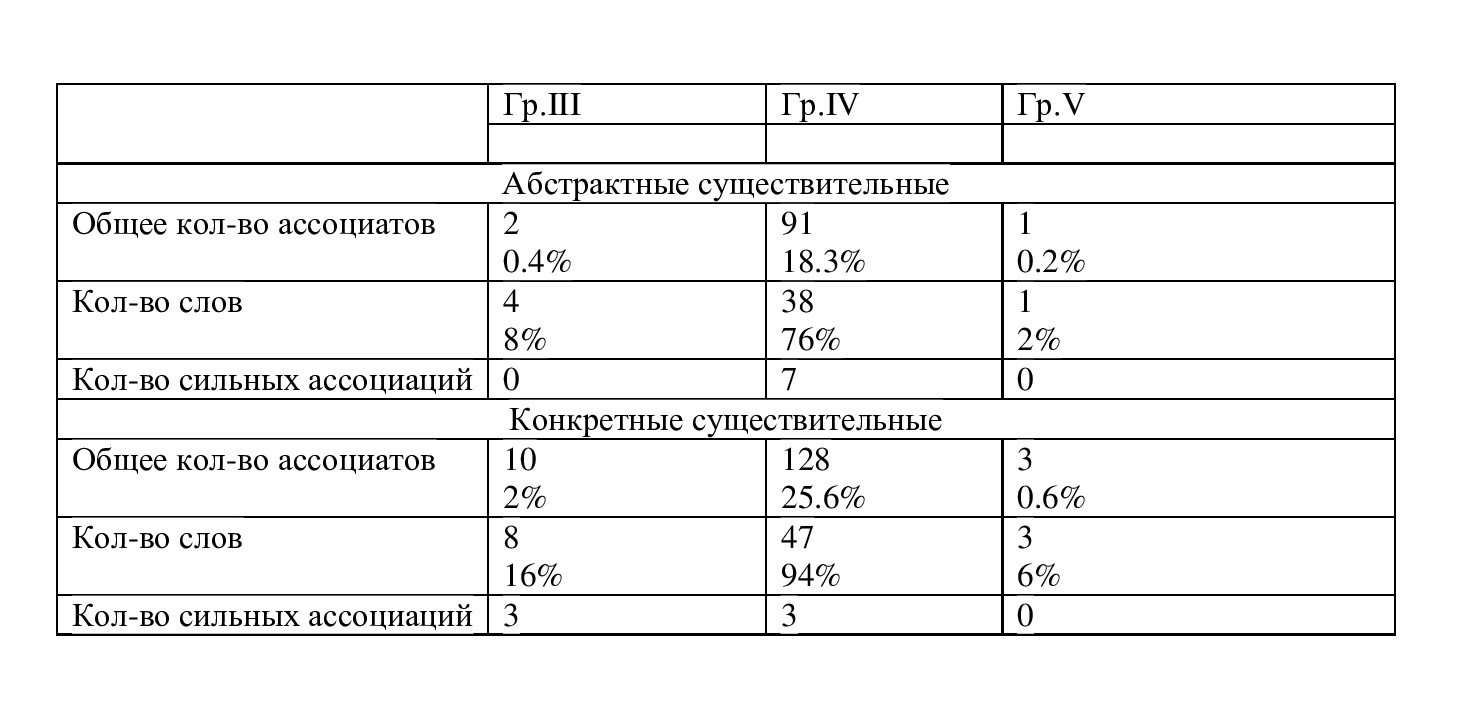

Table 2. Quantitative characteristics of associations with ANs and CNs from Groups 3, 4, and 5

Таблица 2. Количественная характеристика ассоциаций из группы III, IV и V к АС и КС

In Table 2, Gr. 3 means associations that have epidigmatic relations to the stimulus word; Gr. 3 comprises thematically related words and parts of a frame; and Gr. 5 comprises phonetically similar words.

Below are all the associations with ANs, listed in descending order:

- Associations as parts of phrases or set phrases: 39.4 % of the total quantity of associations.

- Adjective associations: 23.8 %.

- Associations as parts of a thematic group or a frame: 18.3 %.

- Synonym associations: 7.9 %.

- Associations as potential parts of phrases or set phrases: 4.8 %.

- Antonym associations: 2.7 %.

- Evaluation associations: 1.0 %.

- Hyponym/hypernym associations: 0.8 %.

- Derived/deriving associations and Associations expressed by proper names: 0.4 % each.

10. Secondary associations and associations as phonetically similar words: 0.2 % each.

Similarly, the descending list of associations with CNs is as follows:

- Adjective associates: 41.2 %.

- Associates as parts of a thematic group or a frame: 25.6 %.

- Associates as parts of phrases or set phrases: 20.8 %.

- Hyponym/hypernym Associates: 5.6 %.

- Associates expressed by proper names: 2.2 %.

- Synonym Associates – 2.0 %.

- Associates being potential parts of phrases or set phrases: 1.0 %.

- Antonym Associates: 0.8%

- Associates as phonetically similar words: 0.6 %.

10. Evaluation Associates: 0.2 %.

There are no quantitative differences between the most common groups of associations (the first three items) with ANs and CNs. However, a closer look at the number of the most frequent Associates indicates a significant difference between the groups of adjective Associates and of Associates as parts of phrases. 16 most frequent responses are among adjective Associates with ANs, while 29 most frequent responses are among adjective Associates with CNs. Among the Associates as parts of phrases or set phrases, only 28 frequent responses are found for ANs and 11 for CNs.

Adjective associates

The very nature of associates is an indicator of qualitative differences.

Firstly, qualitative adjective associates with concrete nouns typically denote one of the properties of the corresponding referent (101). For instance, highway: broad (10), long (5), smooth (5), speed[9] (3), and narrow (3); shirt: white (8), new (3), and light blue (2); suitcase: large (5), heavy (5); juice: sweet (3), sour (3), tasty (2), etc. Adjectives of this group denote human perception of objects via five basic senses, i.e., sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. In this case, the main feature of a concrete noun becomes obvious within the semantic criterion context as they have a visible image of a real referent (Spiridonova, 2000).

Secondly, qualitative adjective associates with concrete nouns may denote hyponymic relations. In such phrases, associates correlate as sub- and super-ordinates. For example, bath: Russian (9), Finnish (sauna) (4); orchestra: wind (23), philharmonic (11), chamber (3); coat: winter (14), light (6), fall (5).

Thirdly, there is one example of a qualitative adjective denoting a basic property of the referent. In this case, the phrase duplicates the general conceptual component from the semantic structure of the stimulus noun, such as sugar: sweet (21).

A group of possessive adjectives – associates is less numerous. For instance, shirt: man’s (3) or egg: of a hen (10). Relative adjectives are found slightly more frequently, such as cabinet: for dresses (8), wooden (7); shirt: silky (3), flannelette (2), etc.

Abstract nouns as stimuli generate responses which to a greater degree are different from those of concrete stimuli.

First, dealing with abstract concepts, a person resorts to comparing and identifies something in common between abstract and concrete referents. Identifications of this kind are in the system of a language: based on the metaphoric similarity of the objects, one adjective may characterize different entities (Spiridonova, 2000). For example: strong rope and strong senses. An abstract concept may be provided with a physical attribute through a new metaphoric meaning of the adjective. This semantic drift does not happen coincidentally. It is assumed that a certain situation may take place, in which a referent of the abstract noun demonstrates characteristics specified by the adjective. Thus, the phrase strong senses implicitly denotes a situation of external action, where the referent does not lose its integrity and continues functioning, that is, it is perceived in the same manner as astrong rope. Identical interpretation of the phrases is also possible, because strong senses take the same position of a patient as the strong rope, i.e., they are on a receiving end of an intense external action that can break the object integrity (Apresyan, 1995).

Such phrases are mostly formed by the adjective associates provided in RAD. E.g., imagination: rich (6), violent (6), rampant (); destiny: bitter (6), hard (3), difficult (2); anxiety: rampant (2); desperation: bitter (3); thought: deep (2); mind: clear (3); future: promising (14); offense: bitter (10), deep (3), burning (2), etc.

Second, qualitative adjectives-associates to ANs often contain the semes of ‘intensity of manifesting the given phenomenon’. For example, the response great occurs 10 times for the stimuli imagination, hatred, happiness, anxiety, wonder, stupidity, sin, prospect, world, and luck; response faint (4) – for the stimulus hope, response strong – for the stimulus curiosity, etc. At the same time, association great also appears as a response to CNs; however, it has the meaning of a size attribute of an object.

Third, unlike adjectives associates to CNs, adjectives and adverbs associated to ANs denote extremely subjective characteristics of the referent. For instance, freedom: desired (2), curiosity: indecent (2); thought: stupid (2) or smart (6), etc.

Fourth, certain adjective associates form set phrases or terminological idioms with the stimulus noun. Only one case of the kind was detected among associates to CNs, i.e. response to the word bullet: random. Few examples of such associations with ANs are as follows: dream: rosy (3) or golden (15); wonder: ordinary[10] (2) or sylvan (2); dimension: the sixth (5) or the fourth (5); stupidity: utter (3); space: three-dimensional (3); sin: original (2), etc.

Associates as parts of phrases or set phrases include the following:

- Associations characterizing possessive relations of the noun referent (Nom. + Gen.): mind: of a human (4); beauty: of a human (3) or of a girl (2); beauty: of people (2); creation: of a writer (7) or of an artist (5); image: of a hero (5), of a girl (5), of a man (4), etc.

- Associates characterizing the noun referent’s focus on the object (Nom.+ Dat./Gen.): confidence: about friend (3) or about people (3); pride: in oneself (4) or in my country (2); love: for a woman (2); hatred: of enemy (11), etc.

- Associates characterizing aspectual relations of the stimulus properties of the noun referent(Nom. + Gen.): ideal: of a man (6), of a woman (5), or of beauty (3); unity: of nations (8), of people (3), of opinions (3), or of views (2); freedom: of word (16), of actions (7), of choice (2), etc.

- Associates, with which the stimulus noun forms set phrases (metaphors), parts of collocations, or titles of books and films. For instance, luck: have a good deal of or rolled in my way; freedom: for parrots; love: and pigeons[11] (2); beauty: will save the world (7); wonder: wigged (6); wonder: tree (2), etc.

Most CN-associates of this group:

1. Characterize certain properties of the object: potatoes: in jackets (2); pillow: downy (2); shirt: checkered (4); cabinet: wooden, etc.;

2. Characterize possessive relations: egg: of a chicken (5), of an ostrich (3); wheel: of a car (7), of a vehicle (4), of a bicycle (3); paw: of a bear (11), of a dog (11), of an animal (6), etc.;

3. Characterize the referent in terms of its actions: bullet: is flying (4); cow: is mooing (3); orchestra: is playing (12); wolf: is howling (2); cup: is broken (3), etc.; and

4. Form set phrases: bullet: doesn’t care who it hits (29), went a-whistling by (2); cat: in a poke (3), in boots (3); blanket: ran away (7); horse: get a horse (10), dappled (5); sword: head of shoulders (5). Concrete nouns are also associated with parts of some set phrases or book titles; however, they are much fewer than the similar AN associates.

Associates as parts of a thematic group are, as a rule, expressed by the units of the same LGC and by the same part of speech as the stimulus word. Such units name similar phenomena that have at least one seme in common with the stimulus word. In some cases, such units are close to synonyms.

Associates as parts of a frame may be units of an LGC, other than that of the stimulus word, and of another part of speech. Such units do not necessarily name similar phenomena; and the semes coincidence is not ubiquitous in this case. Frame components form a figurative representation of a referent situation.

Analysis of the associates of these groups to ANs and CNs shows that the words of similar thematic groups occur more frequently in the associative field of ANs and do not appear in that for CNs, while words that are frame parts occur more frequently in the associative field of CNs and more rarely in that of ANs. The associates below exemplify our findings:

- Associates of the thematic group comprising stimulus and characterizing ANs: loneliness: sorrow (6), sadness (2), mourning (2), boredom (2), fear (2); desperation: fear (3), trouble (2); development: education (2), movement (2); offense: anger (4), sadness (3), pain (2), bitterness (2), animosity (2), etc.

- Associates as parts of frames, characterizing ANs: anxiety: examination (7), trembling (2); art: artist (4), painting (3); imagination: dream (3), painting (2), to paint (2).

- Associates as parts of frames, characterizing CNs: highway: car (7), vehicle (2), asphalt (2); bath: besom (5), to wash (5), shower (2), heat (2), steam (2), sweat bath (2); orchestra: music (9), bandmaster (4), instruments (3), band (2), jazz (2); bullet: pistol (6), gun (5), wound (3), death (2); robe: home (3), warmth (3), bath (2), etc.

Qualitative analysis reveals differences in the associative field forming syntagmatic relations, while quantitative analysis enables to reconstruct the associative field forming paradigmatic relations.

Synonym and antonym associates appear much more frequently in the series of responses to the stimulus expressed by an abstract noun. As shown in Table 1 above, the total number of synonym associates with ANs is 39, which is 7.8 % of the total number of associates; associates of this type are generated to 26 of 50 words. The total number of synonym associates to CNs is 10 (2%); associates of this type are generated for 8 of 50 words.

12 (2.4 %) antonym associates were given to ANs and 4 (0.8%) ones were given to CNs.

This result is consistent with the conclusions regarding a diverse semantic load of abstract nouns, which makes them productive, in terms of the paradigmatic relations of their associates.

However, concrete relations turned out to be more productive in terms of gender-aspect relations. 28 associates (5.6%) to concrete nouns are hyponyms or hypernyms to the stimulus. Associates of this type are generated to 19 words of 50. To abstract nouns, there are only 4 associates (0.8%) that form gender-aspect relations to the stimulus.

We also revealed a significant difference between associates of groups 1 and 2. The most frequent strong associates to CNs are those from group 1 (associating adjectives, participles, and adverbs). Such responses are generated 29 times. We registered 16 associates of this type to ANs. The most frequent associates to ANs are associates representing parts of phrases or collocations. There are 28 associates to ANs and 11 associates to CNs of all the responses of this type.

The degree of abstractness both in associates, and in the database vocabulary play an important role in their semantics. Abstract nouns analysis is complicated as they are usually polysemous, although some of their senses may manifest concrete semantics, or an AN may acquire concreteness in certain contexts (Volskaya, 2022: 37).

Analysis of associates enable to reveal components in the AN semantic structure which affect concretization. For stimulus abstract nouns, they are as follows:

1) 30 associates that are viewed as concrete in the database (the level ranging within 1-2.4). The words woman and examination occur twice. Associates expressed by concrete nouns are registered for 22 stimuli;

2) 29 associates that with an average rating (2.5-3.4) in the database. 4 four words are generated twice: hope, mind, space, and pain. 6 associates have a rating similar to that of concrete nouns, i.e. 2.6-2.8: motion, pain, game, thought, space, and battle; while 6 words with the rating 3.4 are close to abstract nouns: strength, will, power, career, honor, and evil.

3) 42 associates are abstract with ratings 3.5-4.5.

Concrete nouns used as stimuli typically receive concrete associates with ratings ranging between 1-2.4. Only 5 associates have an average rating, though their rating is also close to the concreteness rating of 2.5-2.8.

Abstract stimulus nouns with concrete associations are classified as follows:

1. Object relations in which a feature/action denoted by AN stimuli targets the referent of a CN associate. For instance, for stimulus confidence, the response is friend; while enemy is a response to the stimulus of hatred.

2. The referent of CN response acts as a feature carrier of named AN stimulus. For instance, responses to the stimulus of beauty are woman and girl; response to the stimulus curiosity is woman; art – artist, mind – human, goodness – mom, difficulty – examination, etc.

3. CN denotate becomes a part of the significative value of the AN stimulus. For instance, money is the response to stimuli need and necessity, that is, in the respondents’ subjective perception, need = money and necessity = money.

4. CN referent is the result of the action named by the AN stimulus. For instance, painting is the response to the stimulus art.

5. CN referent is the tool to perform the action named by the AN stimulus. For instance, measurement – ruler.

6. Synonymic or thematic links between words, such as thinking – brain or head; image – icon; religion – church; mind – head; and world – planet.

7. CN referent is the reason for a feature/action named by the AN stimulus. For instance, anxiety – examination.

8. Antonymic bond: peace – war.

Thus, identifying ratings of abstractness/concreteness of associates enables to conclude that the associative field of ANs comprises concrete components, while that of CNs, on the contrary, usually consists of associates of the same LGC only. Therefore, comparing abstract entities with specific objects is of great importance for native speakers while perceiving abstract substantives. This process enriches the semantic structure of abstract vocabulary, which leads to concrete semes occurring in the semantic structure of AN and concretization of certain senses. The process may result in changing the status of a sense from abstract into concrete. This conclusion is consistent with that with the dual-coding theory (Paivio, 1986), according to which only concrete lexical units are directly linked to images and real references, while abstract notions can only refer to images via the concrete ones.

The findings fall in line with (Cousins et al., 2017) who argue that perception of concrete substantives is predominantly based on visual characteristics, while comprehension of abstract words activates both linguistic and contextual resources (Cousins et al., 2017: 52). Researchers of neurobiological mechanisms of perceiving concrete and abstract meanings reveal that concrete words perception implies stimulating all senses of a word to a single sensorimotor prototype and realizing these senses in different situations. The latter creates a representational basis for recognizing senses in other contexts. With abstract nouns, on the contrary, there is a reference to different prototypes (Pulvermüller, 2013: 463). Our conclusions are consistent with that of earlier research showing that concrete words usually occur within a concrete context, while abstract ones do in an abstract context (Frassinelli et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The analysis shows the range quantitative and qualitative characteristics of associates to abstract and concrete nouns characterized.

Based on the analysis of 20-25 associates to each word under the study we conclude that, firstly, the number of single and diverse associates to abstract nouns is higher than the number of those to abstract nouns; therefore, it can be inferred that the semantic load of abstract nouns is more diverse than that of concrete ones. Secondly, concrete nouns have stronger associates than abstract ones, because CN name really existing referents available for perception. The result obtained is a strong vindication of the Context Availability Theory, as exemplified in Russian.

We define the nature of associates to different LGCs, we analyzed 10 associates to each word in the dataset. The most apparent differences between associates to ANs and those to CNs were identified in the following groups: adjective associates, phrase associates, thematic associates, frame, antonym associates, synonym associates, and hypernym/hyponym associates.

We also identified abstractness/concreteness ratings of the associates in our database. Abstract stimuli may receive concrete associates, while only concrete associates are generated to concrete stimuli.

The research findings may be beneficial in the context of discussions on the semantic range of abstract nouns and innate sensorimotor substrate of their semantic structure.

Appendices

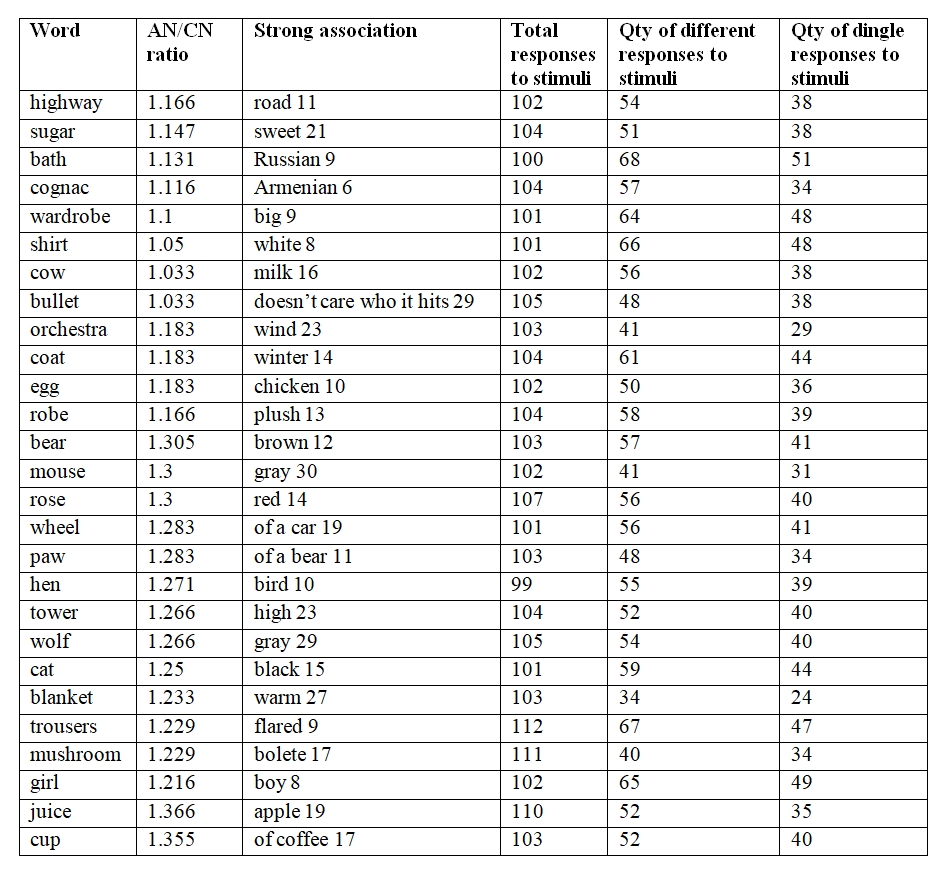

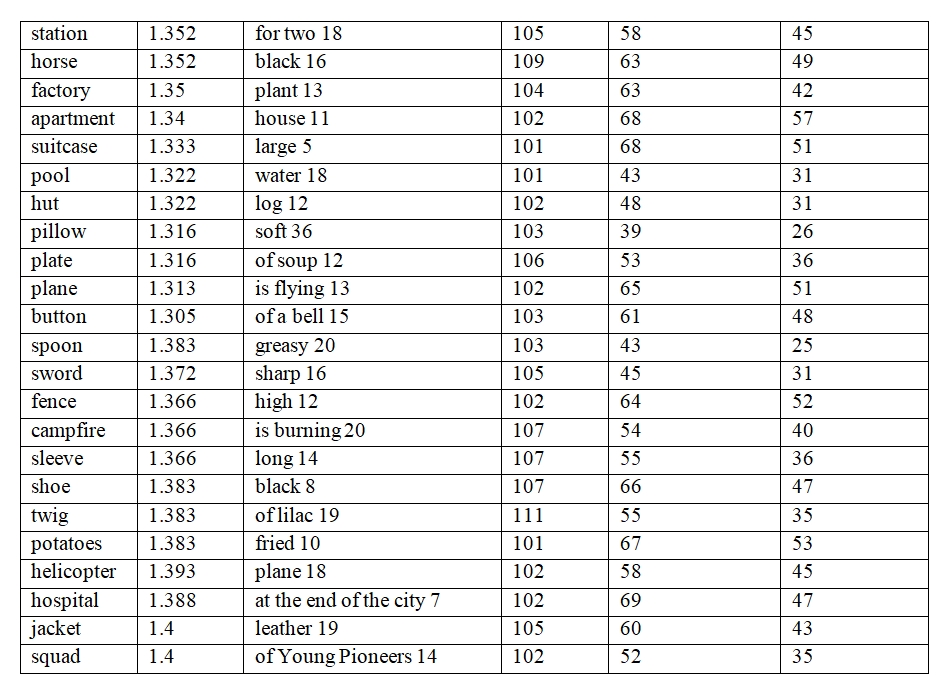

Appendix 1. Associations with Concrete Nouns

Приложение 1. Ассоциации к конкретным существительным

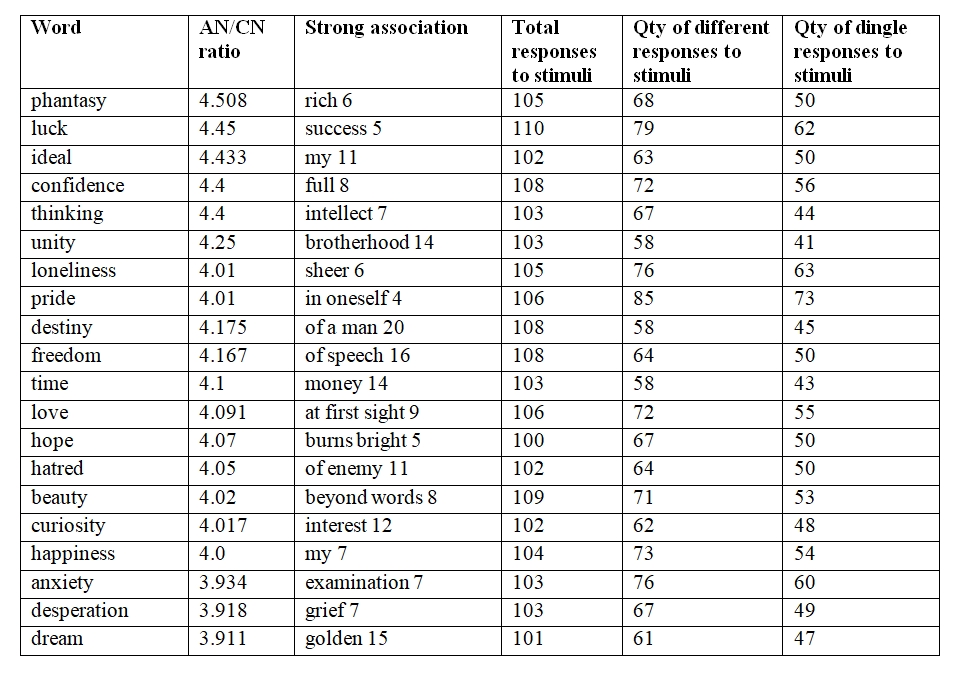

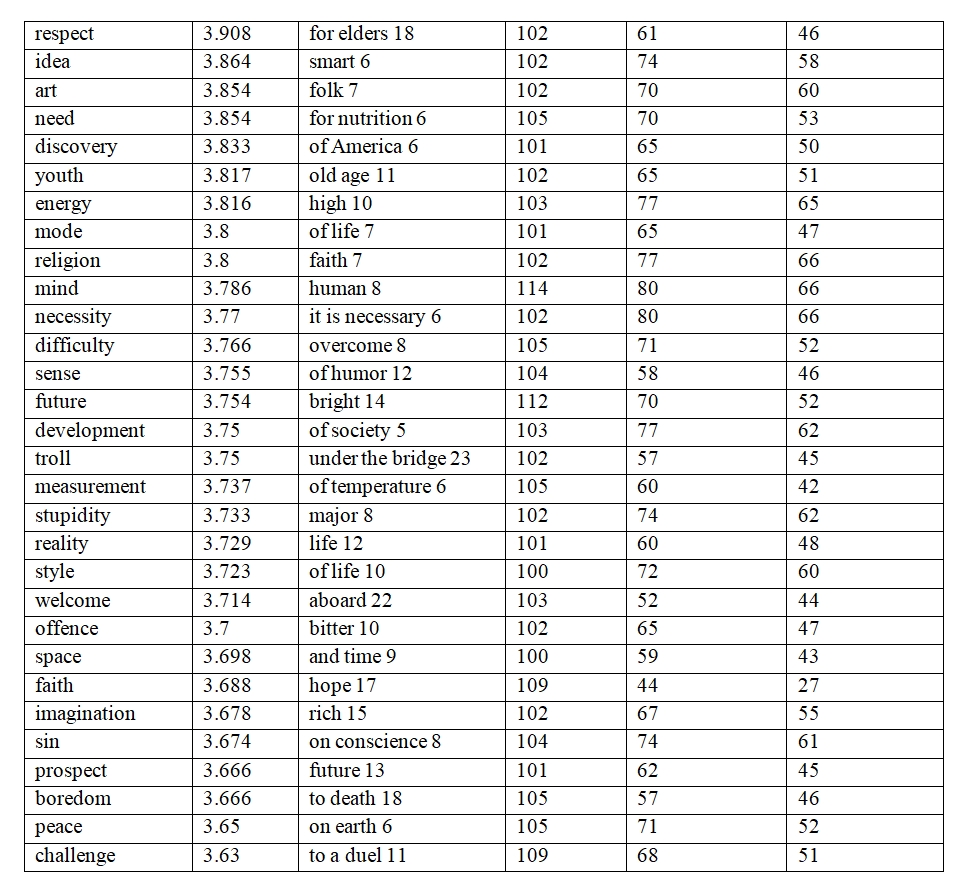

Appendix 2. Associations with Abstract Nouns

Приложение 2. Ассоциации к абстрактным существительным

[1] Karaulov, Yu. N. (1994). Russky assotsiativny slovar [Russian Associative Dictionary], in Sorokin, Yu. A., Tarasov E. F. (ed.), Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

[2] Ufimtseva, N. V. (2004). Slavyanskij associativnyj slovar': russkij, belorusskij, bolgarskij, ukrainskij [Slavic associative dictionary: Russian, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Ukrainian], in Cherkasova, G. A., Karaulov, Y. N., Tarasov, E. F. (ed.), Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

[3] Goldin, V. E. (2011). Russkij associativnyj slovar' : associativnye reakcii shkol'nikov I – XI klassov : v 2 t. [Russian associative dictionary : associative reactions of schoolchildren of I - XI grades : in 2 vols.], in Sdobnova, A. P., Martyanov, A. O. (ed.), Saratov, Russia. (In Russian)

[4] Lyashevskaya, O. N., Sharov, S. A. (2015). Chastotny slovar sovremennogo russkogo yazyka (na materialakh Natsionalnogo korpusa russkogo yazyka) [Frequency Dictionary of Russian, as Exemplified by the Russian National Corpus], 2nd edition, revised and amended, Slovari.ru, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

[5] Abramov, N. (2007). Slovar russkikh sinonimov i skhodnykh po smyslu vyrazheniy: okolo 5000 sinonimicheskikh ryadov, bolee 20000 sinonimov [Dictionary of Russian Synonyms and Semantically Similar Expressions: About 5,000 Synonymic Rows and over 20,000 Synonyms], 8th edition, stereotypic, Rus. Slovari, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

[6]Image and icon, as well as world and peace, are synonyms in Russian.

[7] In combination with orchestrawind and chamber are adjectives in Russian.

[8] Entuziastov Highway is a highway in Moscow, Russia.

[9] Within this context, it is an adjective in Russian.

[10]Ordinary Wonder is a popular Soviet comedy film (1979) by M. Zakharov.

[11]Freedom for Parrots! is a slogan of a Soviet cartoon about Kesha the Parrot (1988), Love & Pigeons is a Soviet film (1985).

Thanks

The reported study was funded by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, Project Number 20-312-90041.

Reference lists

Apresyan, Yu. D. (1995). Leksicheskaya semantika: 2-e izd., ispr. i dop. [Lexical semantics: 2nd ed., corrected. and additional], Izbrannye trudy: v 2 t. [Selected works: in 2 vols], Shkola «Yazyki russkoj kul'tury», Izdatel'skaya firma «Vostochnaya literatura» RAN, Moscow, Russia, V.2 (In Russian)

Bailey, D. J., Nessler, C., Berggren, K. N. and Wambaugh, J. L. (2020). An aphasia treatment for verbs with low concreteness: a pilot study, American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29 (1), 299-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJSLP-18-0257(In English)

Barsalou, W. L. and Wiemer-Hastings, K. (2005). Situating Abstract Concepts, Grounding cognition: The role of perception and action in memory, language, and thought, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 129–163. (In English)

Borghi, A. M., Binkofski, F., Castelfranchi, C., Cimatti, F., Scorolli, C. and Tummolini, L. (2017). The challenge of abstract concepts, Psychological Bulletin, 143, 263–292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000089(In English)

Brysbaert, M., Stevens, M., De Deyne, S. and Voorspoels, W. (2014b). Norms of age of acquisition and concreteness for 30,000 Dutch words, Acta psychologica, 150, 80–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2014.04.010 (In English)

Brysbaert, M., Warriner, A. B. and Kuperman, V. (2014a). Concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas, Behavior research methods, 46 (3), 904–911. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0403-5(In English)

Chen, S. X., Benet-Martínez, V. and Ng, J. C. K. (2014). Does language affect personality perception? A functional approach to testing the Whorfian hypothesis, Journal of Personality, 82 (2), 130–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12040(In English)

Coltheart, M. (1981). The MRC psycholinguistic database, The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 33, 497-505. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14640748108400805(In English)

Cousins Katheryn, A. Q., Ash, Sh., Irwin, D. J. and Grossman, M. (2017). Dissociable substrates underlie the production of abstract and concrete nouns, Brain and Language, 165, 45-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2016.11.003(In English)

Crutch, S. J. and Warrington, E. K. (2005). Abstract and concrete concepts have structurally different representational frameworks, Brain, 128 (3), 615–627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh349 (In English)

Crutch, S. J. and Jackson, E. C. (2011). Contrasting graded effects of semantic similarity and association across the concreteness spectrum, Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64 (7), 1388–1408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2010.543285(In English)

De Deyne, S., Navarro, D. J., Perfors, A., Brysbaert, M. and Storms, G. (2019). The “Small World of Words” English word association norms for over 12,000 cue words, Behavior Research Methods, 51 (3), 987–1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1115-7 (In English)

De Deyne, S. and Storms, G. (2015). Word associations, in Taylor, J. R. (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the word, Oxford University Press, New York, US. (In English)

De Groot, A. M. (1989). Representational aspects of word imageability and word frequency as assessed through word association, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 15 (5), 824–845. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.15.5.824(In English)

Duñabeitia, J. A., Avilés, A., Afonso, O., Scheepers, C. and Carreiras, M. (2009). Qualitative differences in the representation of abstract versus concrete words: evidence from the visual-world paradigm, Cognition, 110 (2), 284–292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2008.11.012(In English)

Frassinelli, D., Naumann, D., Utt, J. and Schulte im Walde, S. (2017). Contextual Characteristics of Concrete and Abstract Words, IWCS 2017 – 12th International Conference on Computational Semantics. (In English)

Goldin, V. E. (2008). Configurations of associative fields and language picture of the world, Yazyk – soznanie – kul'tura – socium: sbornik dokladov i soobshchenij Mezhdunarodnoj nauchnoj konferencii pamyati professora I. N. Gorelova, Saratov, 147-152. (In Russian)

Hanley, J. R., Hunt, R. P., Steed, D. A. and Jackman, S. (2013). Concreteness and word production, Memory & Cognition, 41, 365-377. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0266-5(In English)

Hill, F., Korhonen, A. and Bentz, Ch. (2014). A Quantitative Empirical Analysis of the Abstractness/concreteness Distinction, Cognitive science, 38 (1), 162–177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12076(In English)

Hoffman, P., Lambon Ralph, A. M., Rogers, T. T. (2013). Semantic Diversity: A Measure of Semantic Ambiguity Based on Variability in the Contextual Usage of Words, Behavior Research Methods, 45 (3), 718–730. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0278-x(In English)

Ivanov, V. and Solovyev, V. (2022). Automatic generation of a large dictionary with concreteness/abstractness ratings based on a small human dictionary, Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, Preprint, 42 (5), 4513-4521. http://dx.doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.06200(InEnglish)

Karaulov, Yu. N. (1994). Russkij associativnyj slovar' kak novyj lingvisticheskij istochnik i instrument analiza yazykovoj sposobnosti [Russian Associative Dictionary as a New Linguistic Source and Tool for the Analysis of Language Ability], in Karaulov, Yu. N., Sorokin, Yu. S., Tarasov, E. F., Ufimceva, N. V. and Cherkasova, G. A., Russkijassociativnyjslovar'. Kniga 1 [Russian associative dictionary. Book 1], Moscow, Russia, 191-218. (In Russian)

Kousta, S. T., Vigliocco, G., Vinson, D., Andrews, M. and Del Campo, E. (2011). The representation of abstract words: Why emotion matters, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140, 14–34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0021446(In English)

Loiselle, M., Rouleau, I., Nguyen, D. K., Dubeau, F., Macoir, J., Whatmough, C. and Joubert, S. (2012). Comprehension of concrete and abstract words in patients with selective anterior temporal lobe resection and in patients with selective amygdalo-hippocampectomy, Neuropsychologia, 50, 630-673. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.023(In English)

Lupyan, G., Abdel Rahman, R., Boroditsky, L. and Clark, A. (2020). Effects of language on visual perception, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24 (11), 930–944. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.08.005(In English)

Mate, J., Allen, R. J. and Baqués, J. (2012). What you say matters: Exploring visual–verbal interactions in visual working memory, The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65, 395-400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2011.644798(In English)

McNamara, D., Graesser, C., Mccarthy, P. M. and Zhiqiang, C. (2012). Automated evaluation of text and discourse with Coh-Metrix, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511894664(In English)

Mestres-Missé, A., Münte, T. F. and Rodriguez-Fornells, A. (2014). Mapping concrete and ab-stract meanings to new words using verbal contexts, Second Language Research, 30, 191–223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0267658313512668(In English)

Naumann, D., Frassinelli, D. and Schulte im Walde, S. (2018). Quantitative Semantic Variation in the Contexts of Concrete and Abstract Words, Proceedings of the Seventh Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics, 76–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/S18-2008(In English)

Nishiyama, R. (2013). Dissociative contributions of semantic and lexical-phonological information to immediate recognition, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 642-648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029160(In English)

Oliveira, J., Perea M. V., Ladera, V. and Gamito, P. (2013). The roles of word concreteness and cognitive load on interhemispheric processes of recognition, Laterality, 18 (2), 203-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1357650X.2011.649758(In English)

Paivio, A. (2013). Dual Coding Theory, Word Abstractness, and Emotion: A Critical Review of Kousta et al. (2011), Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142, 282-287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027004(In English)

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual coding approach, Oxford University Press, New York, US. (In English)

Planchuelo, C., Buades-Sitjar, F., Hinojosa, J. A. and Duñabeitia, J. A. (2022). The nature of word associations in sentence contexts, Experimental Psychology, 69 (2), 104-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a00054(In English)

Pulvermüller, F. (2013). How neurons make meaning: Brain mechanisms for embodied and abstract-symbolic semantics, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17, 458-470. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.004(In English)

Sadoski, M. (2001). Resolving the effects of concreteness on interest, comprehension, and learning important ideas from text, Educational Psychology Review, 13 (3), 263–281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1016675822931(In English)

Sadoski, M., Kealy, W. A., Goetz, E. T. and Paivio, A. (1997). Concreteness and imagery effects in the written composition of definitions, Journal of Educational Psychology, 89 (3), 518–526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.518(In English)

Spiridonova, N. F. (2000). Language and perception: the semantics of qualitative adjectives, Ph.D. Thesis, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Schock, J., Cortese, M. J. and Khanna, M. M. (2012). Imageability estimates for 3,000 disyllabic words, Behavior Research Methods, 44 (2), 374–379. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0162-0(In English)

Schwanenflugel, P. J., Akin, C. and Luh, W.-M. (1992). Context availability and the recall of ab-stract and concrete words, Memory & Cognition, 20, 96–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/bf03208259(In English)

Shaposhnikova, I. V. (2022). Associative grammar and meaning (on the example of a noun), Sibirskij filologicheskij zhurnal, 1, 268-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.17223/18137083/78/19 (In Russian)

Solovyev, V. D., Ivanov, V. V. and Akhtiamov, R. B. (2019). Dictionary of Abstract and Concrete Words of the Russian Language: A Methodology for Creation and Application, Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics, 10, 215–227. http://dx.doi.org/10.22055/RALS.2019.14684(In English)

Solovyev, V. D., Volskaya, Y. A., Andreeva, M. I. and Zaikin, A. A. (2022). Russian dictionary with concreteness/abstractness indices, Russian Journal of Linguistics, 26 (2), 515–549. http://dx.doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-29475(In English)

Solovyev, V., Solnyshkina, M., Andreeva, M., Danilov, A. and Zamaletdinov, R. (2020). Text Complexity and Abstractness: Tools for the Russian Language, Proceedings of the International Conference “Internet and Modern Society”, 75-87. (In English)

Spreen, O. and Schulz, R. W. (1966). Parameters of abstraction, meaningfulness, and pronunciability for 329 nouns, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 5, 459-468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(66)80061-0(In English)

Vinogradov, V. V. (2001). Russkij yazyk (Grammaticheskoe uchenie o slove): 4-e izdanie [Russian language (Grammatical doctrine of the word): 4th edition], Russkij yazyk, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Volskaya, Y. A., Zhuravkina, I. S. and Lobanov A. P. (2020). Dictionary of abstract the words of the Russian language: Nouns with high numerical measure of abstractness, International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 9, 2398–2405. https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-4409.2020.09.290(In English)

Volskaya, Y. A. (2022). Sozdanie bazy dannyh abstraktnyh i konkretnyh sushchestvitel'nyh: vopros o vliyanii instrukcij na ocenku slov respondentami [Creating a database of abstract and concrete nouns: the question of the influence of instructions on the assessment of words by respondents], Philology and Culture, 4 (70), 36-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.26907/2782-4756-2022-70-4-36-43(In Russian)

Xu, X. and Li, J. (2020). Concreteness/abstractness ratings for two-character Chinese words in MELD-SCH, PLoS ONEО, 15 (6). http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232133(In English)

Zhuravkina, I., Soloviev, V., Lobanov, A. and Danilov, A. (2020). Comparative analysis of concreteness abstractness of Russian words, Conference of Open Innovation Association (FRUCT), 464–470. http://dx.doi.org/10.23919/FRUCT48808.2020.9087416(In English)