Le Guin's magic in the context of Taoism: reading A Wizard of Earthsea

Abstract

This research examines the role of magic in fantasy fiction, with a particular emphasis on Ursula K. Le Guin's A Wizard of Earthsea (1968). The research shows how the concept of balance is essential to the coming-of-age tale of a young wizard's development into a responsible adult through qualitative thematic analysis of the themes of true name, voyage, and shadow in the novel. The theoretical foundation for analyzing Le Guin's magic is derived from the Taoist philosophy and the Jungian theory of wholeness. Le Guin's portrayal of magic emphasizes the Taoist idea of balance that is realized through the interconnectedness of opposites by showing how mastering magic equips the wizard with knowledge that helps him to see things' real meanings. By choosing the road of balance, the wizard is able to face and reconcile with his darkness, which leads to mental development and completeness. The study's findings support the idea that magic, with its philosophical underpinnings, acts as an internal force that drives the wizard into spiritual maturity and marks a key turning point in the story. A Wizard of Earthsea offers a distinctive viewpoint on the function of magic in the fantasy genre by examining binary interactions within a framework of balance and wholeness.

1. Introduction

Space in literature refers to a location having a story relation. Author Ursula K. Le Guin invents fictitious locations in the Earthsea archipelago in A Wizard of Earthsea (WOE). She elevates her work to the nexus of intellect and beauty in her stories by fusing Eastern philosophical ideas with Western literary styles. One of the three major fantasy books, along with The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien and The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis, is Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea Cycle (1968–2001). The first book of The Earthsea Cycle is the award-winning WOE. J.R.R. Tolkien was knowledgeable about philology and mythology, while C.S. Lewis was a theologian who also wrote. Understanding the tone of their fantasy literature requires an appreciation of their expertise in these particular fields. Le Guin's fantasy writing showcases her knowledge of Taoist philosophy. The awareness of balance, which is the interdependence of opposing aspects, is a recurring subject based on Taoist philosophy.

Novels, short stories, poetry, literary criticism, and translations are among Le Guin's literary forms. A Book on the Way and the Power of the Way, her own poetic translation of the Tao Te Ching, was released in 1997.

1.1 Literature Review

Le Guin's fictional universe is underpinned by three disciplines: anthropology, Taoism, and Jung psychology (Spivack, 1984). Many viewpoints have been used to discuss Le Guin's work. Barbour sees Le Guin's creative vision as dualistic and holistic, reflecting the interaction of two opposing elements: being good results from darkness and being wicked from light (Barbour, 1974). One of the basic concepts of Taoism philosophy, which is a major theme in her work, is the interaction of opposing forces. It seeks humanity by embracing the other through the harmonious interplay of opposing factors (Bain, 1980). The Taoist notion of balance and the Jungian concept of wholeness have a lot in common in WOE. The principles of “wholeness and balance, the equilibrium of cause and effect, and good and evil” are the cornerstones of Le Guin's magic (Galbreath, 1980: 262). The wholeness derived from balance and the reciprocity of Yin and Yang is emphasized in Le Guin's writing (Hunt & Lenz, 2001). WOE portrays the cosmos as being in a balanced system that is maintained by natural rules and is based on Taoism and Jungian philosophy (Aldea, 2008). Le Guin reconsiders the fundamental nature of magic in terms of its capacity to reconcile opposites and its roles as a mediator between people and nature (Huang & Dai, 2021). Taoist dualism advocated by Le Guin aims for oneness by integrating good and evil into the whole. Le Guin uses a Taoist framework to create the "myth and spirit" of Earthsea (Hogsette, 2022).

1.2 Fantasy Literature

Folklore, myths, and legends can be used to trace the history of fantasy literature. According to O'Sullivan (2010), they provide fantastical stories, themes, and characters. Using magic and supernatural beings in the main subject or locations, as well as developing a story in which "forces of good win against a monolithic evil," are characteristics of fantasy (literature) (Timmerman, 1983; Attebery, 2004: 293). A type of romance that tends toward mythology, according to Northrop Frye, is magical stories. Frye states in Anatomy of criticism: four essays that "myth is one extreme of literary design" (Frye, 2020: 136) and "naturalism is the other," with the romance genre of magical tales showing human exploits" (Frye, 2020: 136) falling in the center. Frye places the story of magic in stark contrast to realist fiction which remains faithful to imitation of the empirical world.

1.3 Taoism

The ancient Chinese philosophy Taoism, attributed to Lao-Tzu and Chuang-Tzu, seeks a balance between two opposing forces by acknowledging their interdependence: "Being and non-being develops together (Lao-Tzu, Chapter 2); "The things of this world originate from Being, And Being (comes) from Non-being" (Lao-Tzu, Chapter 40). Under the principle of non-preference, distinction between the opposite, e.g., good and bad, beauty and ugliness becomes irrelevant (Oldstone-Moore, 2003). Lao-Tzu says that a virtue such as beauty or goodness imply its opposite qualities: “something gets ugly when it is thought to be beautiful. Virtue becomes evil when it is perceived as something positive” (Lao-Tzu, Chapter 2); "between good and evil how much difference is there?" (Lao- Tzu, Chapter 20).

Chuang-Tzu’s lesson is that in order to comprehend ten thousand things generally and to make them equal, one must be all-encompassing: Because it is aware that there is no definitive border between right and wrong or between the big and the little, great knowledge sees opposites because it knows that there is no end to the weighing of things” (Chuang-Tzu, Autumn Flood). According to Chuang-Tzu, Taoist View does not recognize “this” and “that” as opposites: “the recognition of right always follows the recognition of wrong: (Chuang-Tzu, Discussion on Making All Things Equal). Chuang-Tzu explains with an example: According to a man, Lady Li is stunning. If birds saw her, they would fly away, and if a deer saw her, they would start running. How can the bar for beauty be raised? Borders were unknown to The Way. Great sages acknowledge both smallness and largeness without thinking either to be useless or burdensome (Chuang-Tzu, Discussion on Making All Things Equal).

The Taoist idea of balance has commonalities with the Jungian concept of shadow and wholeness. Jung, in The Practice of Psychotherapy (2nd Edition, 1966), states that wholeness can be achieved through a spirit that exists in the unity of “I and You” (Jung, 1966: 245), which corresponds to Taoist interdependence. Jung understands that the goal of Taoist ethics is to find deliverance from cosmic tension of opposites (Jung, 1970: 217). Tao is an idea of completeness achieved by “the unity of opposites in the whole” (Jung, 1977: 223).

1.4 Shadow

According to Jung, since the human psyche is the source of the arts, psychology can support the study of literature. The literature exemplifies the psychological assumptions of its makers; literature is understood through psychological acceptance of its interpreters (Jung, 1966a). All criticism and theory start from the assumptions about “the psychology of the humans who are portrayed in literature” (Holland, 1990: 29). The contents of the collective unconscious shared by humans during the evolution of the human mind are known as archetypes (Jung, 1969: 22). Shadow, one of the most important archetypes, is “a personification of the dark side of human nature” (Spivack, 1984: 6). In AION, Jung states that one can become shadow conscious by recognizing the weak and dark aspects of personality as present and real. This act of recognizing “is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge” (Jung, 1959: 8).

The shadow is a tight passage through which one must pass to find one’s true self (Jung, 1969). Recognizing one’s own shadow must be one of important psychological tasks in life (Walker, 2002). According to Esmonde, the shadow is the dark half of the human totality, without which the light half lacks body and humanity. The unity of light and shadow is the individuation process by which a person achieves “the integration of ego and shadow” (Esmonde, 1979: 17). The process of individuation implies the confrontation with personal unconscious in which opposites are “balanced to create a new unity” (Huskinson, 2004: 44). The union of opposites allows an individual to develop a unified, rational, and unique personality (Hopcke, 1999). Jung’s individuation is characterized by the acceptance and overcoming of opposites, as does Taoism (Rosen, 1997).

In her essay “The Child and Shadow” Le Guin refers to Jung’s idea: Fantasy is mainly about the “journey into the subconscious” (Le Guin, 1975: 144) trying to understand the dark side of our existence. Le Guin argues that the shadow is “the dark brother of the conscious mind” (Le Guin, 1979: 63), which is one’s disillusioned selfishness that is repressed in the process of becoming a cultured adult. ‘Becoming a civilized adult’ is the ultimate stage of human achievement (Smith, 1990), which in Jungian terms is wholeness.

All fictions, including Fantasy, are metaphors that explore another world in its mystical reality and suggest a renewed insight (Le Guin, 1969; Armitt, 2005). Le Guin conveys the perception of balance through the metaphor of journey leading “from here to there, from self to Other” (Cummins, 1993: 16). The main narrative of WOE follows “hero’s coming-of-age” (Le Guin, 1979: 55) pattern which describes the adventure of a young wizard chasing an intimidating ‘shadow’. Coming-of-age narrative delineates the intellectual and social development of a central figure who, undergoing memorable experiences, gains an “affirmative view of the world” and comes to “a better understanding of self” (Hardin, 1991: xiii). The courageous act of confronting the antagonist is a conventional code of a Fantasy hero. Le Guin uses this code as a metaphor for the basis of the development of self-knowledge (Slethaug, 1986).

1.5 Purpose

This paper’s goal is to examine the implication that Le Guin’s magic possesses in a fantasy book A Wizard of Earthsea within the context of Taoist philosophy. Based on Taoist principles and Jungian theory, this study adopts hero's journey narrative to follow the wizard's passage to maturity.

2. Materials and Methods

The Taoist works of Lao-Tzu and Chuang-Tzu, Jung's collected works, and Le Guin's novel serve as the primary sources for the data. Secondary writings include her biography, relevant literature, and pieces of critical analysis.

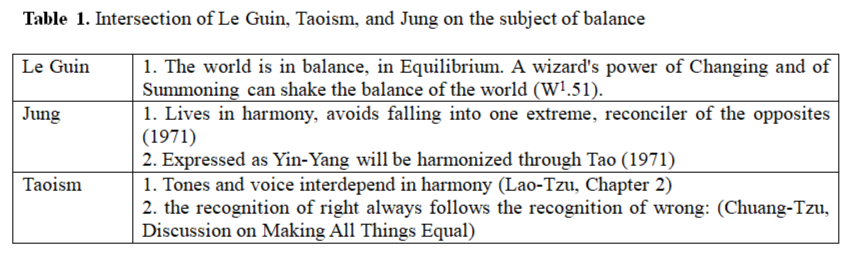

To understand Le Guin's magic in this study, the researcher employed qualitative analysis, which included the Taoist concept of balance. First, in this qualitative research method, facts and details were observed and interpreted by doing close reading (Kain, 1998). The information gathered was divided into true names and balance. Reports were produced after data gathering and categorization. The researcher looked at two datasets to assess their applicability because this research mixes psychology and philosophy. Table 1 provides examples.

Table 1. Intersection of Le Guin, Taoism, and Jung on the subject of balance

3. Findings

WOE is a tale about a goatherd boy Duny (also called sparrowhawk and later Ged). He, born with a magical gift, grows into a responsible wizard through a series of magic training and adventures. In his innate gift lies the danger of arrogance and ambition which may throw him into darkness. The primary lesson he learns at the wizard school is to observe the delicate balance of the universe: "the world is in balance, in Equilibrium" (W.51); "equilibrium would fail" (W.55) if a magic power is used recklessly. For instance, calling down rain on one area of the island without any specific purpose may bring “drought" to another area of the archipelago; calm weather in the East could bring "storm and disaster" to the West (W.63).

Wizards must be assured of "what good and evil will follow on that deed" before changing even one grain of sand (W.51). Ged discovers that the fundamental source of magic knowledge is the notion of interdependence: the craft in a man's hand and the knowledge in a tree's root “they all arise together" (W.193). However, in competing the magic power with his rival schoolmate, Ged disturbs the balance when he accidently summons a shadow from the dark world. Since this incident Ged is constantly chased by the shadow and tested by malevolent being. When he eventually encounters the shadow he realizes that the shadow is his hidden self, not an enemy. The shadow symbolizes Ged's unidentified pride, desire for power and control, and fear of his death (Cummins, 1993).

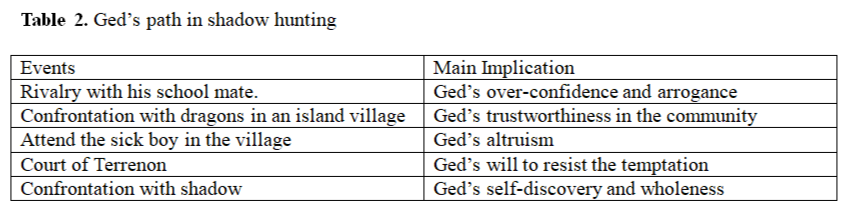

The boy’s development from a novice wizard into a responsible one while chasing the shadow can be classified into the “separation-initiation-return” narrative pattern (Campbell, 2008: 23). Table 2 shows Ged’s adventure he undertakes in his growing path.

Table 2. Ged’s path in shadow hunting

3.1. Separation

In this stage, the protagonist moves from the familiar world into a realm of supernatural wonder, where he overcomes a series of obstacles (Campbell, 2008). At the age of thirteen, Duny participates in the rite of passage ceremony following Earthsea tradition, receives his true name ‘Ged’ from the renowned mage Ogion, and leaves his village to become Ogion’s apprentice. This is Ged's first separation from the accustomed world.

Ogion is a quiet magician whose "listening stillness would fill the room," (W.22). His tranquility reflects the attitude of the Taoist sage whose “enlightened spirit accomplishes without doing, teaches without talking" (Lao-Tzu, Chapter 2). Ogion emphasizes that using sorcery will produce the outcome either “for great, or for bad" (W.27) depending on how it is used (W. 27). Nevertheless, Ged opens his master's ancient book that contains a spell to summon “the ghosts of the dead" to demonstrate his abilities (W.25). This careless gesture awakens "a shapeless clump of darkness" (W.26). Because of this occasion and his "desire for grandeur and the drive to act," Ged is given the chance to enroll in a wizarding school (W. 28). It's Ged's second time venturing into unfamiliar terrain.

3.2. Initiation

The protagonist crosses over into this stage, where he encounters a number of difficulties in an unknown setting (Campbell, 2008). Fantasy creates an antagonist that causes anxiety and fear in the balance of good and evil. Instead of being an external force, the antagonist in WOE is revealed to be the protagonist’s internalized alter ego.

Ged's overconfidence prevents him from becoming a great wizard when he is attending magic school. Being tempted to win the competition, he uses his magic to call an evil shadow from the darkness. His conceit "affects the equilibrium of light and dark, life and death, and good and evil" (W.77). After this incident, the story revolves around Ged's pursuit of shadow to "reverse the evil" (W.77) and restore harmony.

Earthsea magic is neither the art of creating illusions nor tricks to overcoming conflicts. Dexterity and magic spells can make a stone appear like a diamond, but it's nothing more than an illusion that fools “the beholder’s senses” (W.50). The goal of magic is to comprehend the essence of a world held in “balance of light and dark” (W.73). To capture its essence Le Guin’s magic works in relation to the invisible power of language “in which things are named with their true names” (W.21). Magic begins with discovering an object’s true name and progresses to understanding a harmonious tension between conflicting parts. It aims at working on the basis of wholeness, balance, and the equilibrium to understand the nature of things (Galbreath, 1980). Magic plays an indispensable role in building a link based on the name between human perception and their external world (Huang & Dai, 2017). According to Taoist philosophy, the name refers to the source of all being: "the Named is the Mother of All Things," (Lao-Tzu, Chapter 1). Earthsea magic consists of the "true naming of a thing" in Old Speech (W.54). Knowing the real name of an object or a person is equivalent to the ability to “influence it, change it, or even control it” (W.21). The ability to discern the true name is a prerequisite in performing true magic because language is "linked with the nature of all things," (W.55). Therefore, seamasters are required to know "the actual name of every drop of water in the sea" (W.54); and wizards are supposed to recognize "sight, fragrance, and seed" (W.20) of flowers and know their names. Under the tutelage of the great Ogion, young Ged observes each living things “through the woods and over wet green fields in the sun” (W.22). As a result of his interactions with nature, Ged gains the knowledge that human life is part of the world and that “the balance must obtain on an ecological plane as well as on the human” (Crow & Erlich, 1979: 209).

The education he received at the magic school helps Ged participate in the community as a responsible mage (Tikiz & Çubukçu, 2016). His first task is to defend a village from the threat of a dragon. The dragon tests Ged's commitment to the village; he offers Ged an attractive clue about the shadow’s name in exchange for its safe exit from the village. Ged could have accepted the offer by deceiving the villagers, but “he set hope aside and did what he must do” (W.108). Instead, Ged subdues the dragon by calling its real name: "Yevaud, I know your name" (W.107).

When a villager's child falls ill, Ged selflessly uses his gift to save him from death, but he fails as he ignores the rule that "let the dying spirit go" (W.94) without upsetting the natural balance between life and death. When Ged, following the soul of a dying child, approaches the border between life and death, he finds an evil shadow there waiting for him: "across the wall, confronting him, there was a shadow" (W.96). Eventually he comes to life with "grief for the murdered youngster and a dread for himself" (W.98). He challenged the natural division between the living and dead by risking his life in a selfless effort to save the youngster (Spivack, 1984).His attempt to "push back darkness with his own light" (W.51) did nothing but cast a new shadow and upset the balance between life and death.

Along the way, Ged is tricked into entering the Court of Terrenon by a gebbeth which "is something like a shell or a mist in the form of a man" (W.126). If Ged had succumbed to the Court's temptation to use darkness "to combat the darkness," he might have lost his soul. Ged knows, however, that "it is light that kills the dark"(W.139-140). He transforms himself as a hawk and flees. With his commitment to ending evil, Ged, together with his classmate Vetch, embarks on his next journey to confront the evil shadow. In Earthsea, a person's true name is only known to "himself and his namer" (W.81). Vetch and Ged's friendship and "unshakable trust" stems from sharing their true names (W.82). Vetch is a friend who helps Ged keep his balance during the hunt (Zimmerly, 2018). On board the ship, they must respect the standards of balance and silence. Casting a spell on board could upset the balance of power and fate. As they move to where light and darkness meet, they must remember that "those who journey thus say no word carelessly" (W.195).

When Ged finally confronts the shadow, he and the shadow both call each other by the same name ‘Ged’. Thus “the two voices become one voice; and light and darkness met, and joined” (W.211). Sharing the name with the shadow, Ged realizes that the shadow is not an enemy but a crucial part of himself. Ged transforms into a complete being who "cannot be manipulated or possessed by any force other than himself" (W.213). Ged’s reconciliation with the shadow reflects Le Guin’s vision of interdependence.

3.3. Return

In this stage, the protagonist carries the award as he returns to his rightful place. Ged’s growth as a wizard and a person is the reward he received. As a young wizard, Ged enters the magical realm with overconfidence and impatience. After being placed through a series of trials that try his integrity, he emerges as a man of “knowing his whole true self” (W. 213).

4. Discussion

The fictional world portrays universal challenges and functions as a platform for the pursuit of truth (Le Guin, 1994). The idea of balance is one of the truths Le Guin pursues. In WOE, the concept of balance refers to bridging the gap between dualistic opposites and achieving wholeness. This suggests the interconnectedness of being and not-being, to use Lao-Tzu’s terminology. Jung’s idea of wholeness that binds I and You (1996) is represented by the interdependence of seemingly opposite elements. Le Guin develops the coming-of-age tale in which her idea about balance is explicitly realized through the subject of magic and journey, drawing on Taoist ideas and Jungian theory (Spivack, 1984; Aldea, 2008).

Fantasy is a journey into the subconscious mind (Timmerman, 1983). The novel revolves around the protagonist’s battle with the shadow; first his attempt to escape from it, then his decision to hunt it down, and eventually his confrontation with it (Slusser, 1986). In WOE, the protagonist Ged sets out on a risky quest to restore the damage that his arrogant behavior has caused, in contrast to other fantasy heroes who embark on an adventurous journey to achieve personal glory and triumph. His training in magic school serves as a mental compass on his quest, helping him overcome a feeling of fear, thwart temptation, and follow the correct path. Ged is inspired by the practice of magic to consider the moral and ethical use of knowledge that results from his inner equilibrium. (Slethaug, 1986).

In WOE, magic with Taoist wisdom that stresses the interdependence of opposing elements in a state of equilibrium leads the protagonist's transition to the stage of intellectual and social growth. In a series of adventures, Ged's magic knowledge helps him get closer to the degree of wholeness and equilibrium that is the ideal condition for a human being. The first significant event is his magic contest with his rival schoolmate during which his conceit causes him to call forth a shadow from the dark world. Ged is obligated to repair the harm he has done and restore the balance that has been upset by the shadow. The dragon that poses a threat to the community where he lives is his first obstacle to overcome. He succeeds in resisting the dragon’s lure and protecting the village by demonstrating the power of true name that he learned in magic school. Other times, his awareness of his equilibrium prevents him from defiantly crossing the line between life and death. When Ged was tricked into entering the Court of Terrenon by the malicious gebbeth his metamorphosis ability rescued him from the attack. The wisdom he gets during magic training serves as his fundamental tool for overcoming challenges.

In conventional Western storytelling, light and darkness are often interpreted as a symbol of good and evil, “which are constantly in conflict” (Cummins, 1993: 46). In WOE, Ged’s journey revolves around his encounter with an evil shadow, which is a conflict between good and evil. It questions the traditional dichotomy that distinguishes between good and evil, darkness and light, and sees the latter as inferior. By exchanging the same name with the shadow, Ged realizes that the shadow which represents his dark side is a subject of coexistence rather than exclusion. Ged embodies the all-encompassing principle of Chuang-Tzu. By accepting the shadow as a hidden aspect of himself, the wizard gains spiritual maturity. Jung calls it wholeness which transcends boundaries between ‘self and other’. In WOE, the distinction between I and the Other is not what separates them, but what unites them. In Le Guin’s magic tales, the idea of dichotomy is replaced by the idea of harmony.

Le Guin’s Taoist perspective can be seen in the inscription “Creation of Ea”, the oldest song in the Archipelago. The interplay of contrasting words in poetry e.g., “only in dark the light” “only in silence the word”, and “only in dying life” are the core principles of Taoism: “Tao creates the universe, and the universe carries Yin and Yang. Through the union of these two elements, the universe reaches harmony” (Lao-Tzu, Chapter 42). This Taoist idea translates into a magic school curriculum that teaches about maintaining the Equilibrium (Hogsette, 2018). The verse, which ends with “bright the hawk's flight on the empty sky", describes Ged’s leap into a broader universe as a mature mage and adult.

Underlying Le Guin’s magical world is the Taoist ethic of balance. In her philosophical and psychological narratives, Le Guin transforms the tension created by opposing forces into equality and balance.

5. Conclusion

This study examined how magic functions in the fantasy book A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin. WOE has elements that are common to fantasy literature. The main character Ged, who possesses a magical power, embarks on a journey to a foreign land to hunt the evil shadow that he unintentionally let loose upon the world. He faces a number of difficulties that put his courage and integrity to the test but manages to complete the mission and return to the proper location. Given Campbell's narrative framework, the following can be said about Ged's trip in chasing the shadow: Ged departs from his familiar surroundings, ventures into unfamiliar territory, experiences life-changing events, and returns to the starting point with benefits to his development as a wiser and more experienced individual. In this process of his growth the most important attribute of a wizard is intuition and insight drawn from Taoist idea, with which a wizard can see the underlying patterns and meanings in things.

Le Guin uses magic to illustrate Taoist principles of equilibrium and balance. Earthsea magic attempts to connect human experience to the harmony of the natural world by penetrating the true names that contain the essence of things. There is no illusion or ‘deus ex machina’ in Earthsea magic. The wizards are taught to observe and maintain the world's equilibrium. Magic holds the secret to overcoming every obstacle Ged faces along the way and directs him to take the right route at every step of his journey. The essence of magic that respect the true name and balance is best exemplified by Ged's meeting with the malicious shadow. Ged, with his knowledge about true name, succeeds in joining with the shadow and reaching the level of mental development that Jung refers to as wholeness. Ged’s reconciliation with the shadow exhibits Le Guin’s rejection of the dichotomous thinking that divides good and evil.

Le Guin's story rejects the hero myth. It suggests the possibility of fused duality and the balance in human conditions. By pushing through the mental threshold and obtaining Taoist insight – the interdependence of relative opposites and the unity with the Other – the protagonist’s physical journey around the Earthsea is internalized as a psychological adventure.

Corpus Materials

Campbell, J. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces, New World Library, Novato, USA. (In English)

Chuang-Tzu (2013). The Complete Works of Zhuangzi, Translated by Watson, B., Columbia University Press, New York, USA. (In English)

Hopcke, H. (1999). A Guided Tour of the Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Shambhala, London, UK. (In English)

Lao-Tzu (1948). The Wisdom of Laotse, Translated by Lin, Yutang, Modern Library, New York, USA. (In English)

Le Guin, U. K. (1975). The child and the shadow, The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, 33 (2), 139-148. (In English)

Le Guin, U. K. (1994). Fisherman of the Inland Sea, A Gollancz eBook. (In English)

Le Guin, U. K. (2004). A Wizard of Earthsea, Spectra eBook. (In English)

Le Guin, U. K. and Wood, S. (eds.). (1979). The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, Perigee Books, New York, USA. (In English)

Reference lists

Aldea, B. (2008). Balancing opposites, the fictions of Ursula K. Le Guin, Philologia. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai, 1, 157-162. (In English)

Armitt, L. (2005). Fantasy Fiction: An Introduction, Continuum, New York, USA. (In English)

Attebery, B. (2004). Fantasy as mode, genre, formula, in Sandner, D. (ed.), Fantastic Literature, Praeger, London, UK, 293-309. (In English)

Barbour, D. (1974). Wholeness & balance in the Hainish novels of Ursula K. Le Guin, Science Fiction Studies, 1 (3), 164-173. (In English)

Cummins, E. (1993). Understanding Ursula K. Le Guin, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, USA. (In English)

Esmonde, M. P. (1979). The Master pattern: The psychological journey in the Earthsea Triology, in Olander, J. D. and Greenberg, M. H. (eds.), Ursula K. Le Guin, Taplinger Publishing Co, New York, USA, 15-35. (In English)

Frye, N. (2020). Anatomy of criticism: four essays, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA. (In English)

Galbreath, R. (1980). Taoist Magic in the Earthsea Trilogy, Extrapolation, 21 (3), 262-268. (In English)

Hardin, J. (1991). Reflection and Action, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, USA. (In English)

Hogsette, D. S. (2018). The Way of the Fantasist: Ethical Complexities in the Taoist Mythopoeic Fantasy of Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, in Stratman, J. (ed.), Teens and the New Religious Landscape: Essays on Contemporary Young Adult Fiction, MacFarland and Company, Jefferson, USA, 171-188. (In English)

Hogsette, D. S. (2022). The Transcendent Vision of Mythopoeic Fantasy, McFarland and Company, Jefferson, USA. (In English)

Holland, N. N. (1990). Holland's Guide to Psychoanalytic Psychology and Literature-and-Psychology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Huang, Y. and Dai, H. (2017). Fantasy and Taoism in The Earthsea Cycle, Advances in Literary Study, 5, 39-55. https://doi.org/10.4236/als.2017.53005(In English)

Huang, Y. and Dai, H. (2021). A Taoist Study of Magic in The Earthsea Cycle, Religions, 12 (3), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030144(In English)

Hunt, P. and Lenz, M. (2001). Alternative Worlds in Fantasy Fiction, Continuum, New York, USA. (In English)

Huskinson, L. (2004). Nietzsche and Jung: The Whole Self in the Union of Opposites, Brunner-Routledge, London, UK. (In English)

Jung, C. G. (1959). AION, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA. (In English)

Jung, C. G. (1966). The Practice of Psychotherapy (2nd Ed.), Routledge, London, UK. (In English)

Jung, C. G. (1966a). Psychology and Religion, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, USA. (In English)

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (2nd Ed.), Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA. (In English)

Jung, C. G. (1970). Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (2nd Ed.), Routledge, London, UK. (In English)

Jung, C. G. (1977). C. G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and encounters, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA. (In English)

Kain, P. (1998). How to do a close reading, Writing Center at Harvard University, USA. (In English)

O’sullivan, E. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Children’s Literature, The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, USA. (In English)

Oldstone-Moore, J. (2003). Taoism: Origins, Beliefs, Practices, Holy Texts. Sacred Places, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Rosen, D. (1997). The Tao of Jung: The Way of Integrity, WIPF & Stock, Eugene, USA. (In English)

Slethaug, G. E. (1986). The paradoxical double in Le Guin's A Wizard of Earthsea, Extrapolation, 27 (4), 326-333. (In English)

Slusser, G. E. (1986). The Earthsea trilogy, in Bloom, H. (ed.), Ursula K. Le Guin, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, 71-84. (In English)

Smith, C. D. (1990). Jung’s Quest for Wholeness: A Religious and Historical Perspectiv, State University of New York Press, Albany, USA. (In English)

Spivack, C. (1984). Ursula K. Le Guin, Twayne Publishers, Boston, USA. (In English)

Tikiz, G. and Çubukçu, F. (2016). The Act of Wizardry and the Development of a Wizard within a Constructivist Perspective: Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, Humanitas, 4 (8), 323-341. https://doi.org/10.20304/humanitas.277553(In English)

Timmerman, J. H. (1983). Other Worlds: the fantasy genre, Bowling Green University Press, Bowling Green, USA. (In English)

Walker, S. (2002). Jung and the Jungians on Myth, Routledge, London, UK. (In English)

Zimmerly, S. M. (2018). Finding Balance Through Friendship: Reading A WIZARD OF EARTHSEA, The Explicator, 76 (1), 8-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00144940.2018.1430676(In English)