Синестетическая метафора и ее воспроизведение в переводе с русского языка на английский: фреймовый анализ

Aннотация

В статье освещаются разные подходы к пониманию языковой синестезии и синестетической метафоры. Именно синестетическая метафора является основной формой языковой синестезии и образует особый тип метафоры с двумя перцептивными доменами. В переводоведении предлагаются модели перевода метафоры, однако стратегии перевода языковой синестезии до сих пор мало изучены и не систематизированы. Данное исследование было предпринято с целью восполнить этот пробел и выявить когнитивные стратегии, используемые англоязычными переводчиками при осмыслении и интерпретации русских синестетических метафор. Также в центре внимания – проблема выявления семантических универсалий и сдвигов в понимании межмодальных отношений в разных языках и у разных переводчиков. Новизна исследования заключается в разработке типологии переводческих стратегий, применяемых для синестетических метафор. Впервые в исследование синестетической метафоры было интегрировано сразу нескольких методов, разработанных в рамках разных лингвистических теорий: фреймовой семантики, концептуальной теории метафоры и теории перевода в той ее части, которая относится к переводу метафоры. Сочетание разных методов в одном исследовании позволило выявить восемь основных переводческих стратегий – от полного или частичного воспроизведения авторской синестезии до полной утраты синестетического эффекта в тех случаях, когда исходные синестетические метафоры переводятся гипаллагой, сравнением и неметафорой. Синестетические сдвиги или полное опущение синестезии при переводе можно списать на объективные лингвистические различия между исходным и переводным языками и на культурные расхождения между автором и переводчиком-интерпретатором. Однако часто причиной утраты исходной синестезии в процессе перевода является индивидуальное переводческое решение, что легко обнаруживается при сравнении разных переводов одной и той же метафоры.

Ключевые слова: Синестезия, Синестетическая метафора, Межмодальные переносы, Фреймовый анализ, Семантические сдвиги, Перевод метафоры, Условия для когнитивного переноса

К сожалению, текст статьи доступен только на Английском

Introduction

Linguistic synaesthesia (sweet voice or sharp sight) is conventionally studied from the angle of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT), according to which metaphors are grounded in our conceptual system, while language units are just verbal manifestations of the underlying conceptual metaphors. Metaphoric conceptualization means cross-domain mappings following a unidirectional pattern – from source to target domain (Lakoff, Johnson, 2003). Seemingly, with CMT approach we have to take metaphoricity of synaesthetic expressions for granted. However, the assumption is debatable. Before we clarify our understanding of linguistic synaesthesia and shift focus to synaesthetic metaphors, let us draw attention to the most controversial issues that pose a challenge to sensory language researchers.

As far as linguistic synaesthesia is concerned, some scholars question two fundamental principles of CMT, i.e. unidirectionality and asymmetry of cross-domain transfers, co-relation between concreteness-abstractness of two domains with a stronger influence of the source domain onto the target domain than vice versa. The thing is that the both domains in synaesthesia pertain to perception, which gives rise to speculations about non-metaphoric nature of cross-modal transfers (Rakova, 2003; Winter, 2019). However, S. Ullman revealed certain succession in synaesthetic mappings and suggested a hierarchical principle of synaesthetic transfers from the lower sensory modalities to the higher ones (hearing, vision ← touch, taste, smell) (Ullman, 1957). Later S. Ullman’s findings were confirmed, his hierarchical model was elaborated and enhanced (Shen, Cohen, 1998; Yu, 2003; Strik Lievers, 2015) and newly obtained empirical data added substantially to consistency of the hypothesis (Zhao, Huang, Long, 2018; Kumcu, 2021). Neuroscientists explain the directionality principle of cross-sensory correspondences by “anatomical constraints that permit certain types of cross-activation, but not others” (Ramachandran, Hubbard, 2001: 18).

In search of the conceptual basis of linguistic synaesthesia scholars tend to refer to cross-sensory blendings as image schemas, i.e “recurring patterns of particular bodily experience, including perceptions via vision, hearing, touch, kinesthetic perception, smell and possibly also internal sensations such as hunger, pain, etc.” (Grady, 2005: 45). According to B. Hampe, image schemas are embodied, pre-conceptual structures arising from our sensor-motor experience and integrating multiple modalities (Hampe, 2005: 1). J. Grady insists on differentiation between image schemas and other conceptual structures on the assumption that “sensory/perceptual concepts have a special status in human thought” (Grady, 2005: 45). Other authors who share the same approach tend to construe synaesthetic expressions in terms of image schema metaphors (Popova, 2005; Löffer, 2017). However, recently a number of scholars have questioned the relevance of purely schematic approach towards linguistic synaesthesia arguing that CMT in general and image schema theory in particular ignore the dynamic nature of synaesthesia (Wiben, Cuffari, 2014; Müller, 2016; Wiben, 2017). Synaesthetic metaphors in discourse often go beyond the framework of somewhat rigid postulates of CMT and novel creative metaphors do not always fit in a schema.

The attempts to reconcile different approaches should be highly appreciated. According to S. Shurma and A. Chesnokova, a synaesthetic expression like any language sign forms a triad of three images – image schema (pre-conceptual level), mental image (conceptual level) and verbal image (linguistic level) (Shurma, Chesnokova, 2017). It means that linguistic synaesthesia stems from inter-projection of source-to-target image schemas, gestalt-like embodied structures; in discourse basic image schemas develop into concepts bridging our bodily and socio-cultural experiences; the verbal representation of a synaesthetic concept acquires its material form in words, phrases or even text parts. Importantly, however universal concepts of taste, touch, hearing or vision are, language always assigns additional meanings (variations) to synaesthetic expressions, which finds evidence in cross-cultural studies (Caballero, Paradis, 2015; Strick Lievers, 2016; Smirnova, 2016; Kalda, Uusküla, 2019). We claim that linguistic synaesthesia cannot be reduced to metaphor; it exploits other, non-metaphoric, codes as in запахзагара ‘smell of suntan’ (metonymy) or курчаво-зеленыегоры ‘curly green mountains’ (metaphor-metonymy). However, it is the synaesthetic metaphor that dominates linguistic synaesthesia at conceptual and verbal levels encoding cross-modal co-associations in a variety of patterns.

Hence, in this paper, linguistic synaesthesia is seen as a dynamic phenomenon arising from image schemas and growing into complex concepts under the impact of context-dependent factors. Synaesthetic metaphors form a specific class of metaphors with the both domains pertaining to perception. Synaesthetic transfers reveal certain regularities, i.e., cross-modal mappings generally occur in one direction – from the lower to the higher senses. When created, synaesthetic metaphors walk the same conceptual paths as any other metaphors – from searching for conceptual similarities and fixing conceptual conflicts to generating a new (metaphoric) meaning. The synaesthetic metaphor is both the product of perception (image schema), conceptualization (concept) and the verbal manifestation of the underlying cross-sensory integration (word or phrase).

We look into linguistic synaesthesia through the prism of a cognitive paradigm in Metaphor Translation Studies (MTS). Actually, “a cognitive approach, as a theoretical framework, …unfolds the true nature of metaphor …and can account for the actual occurrences, including divergent translation solutions and translator-related factors” (Hong, Rossi, 2021: 20, 22). What is more, a linguo-cognitive perspective in metaphor translation research brings to light strategies and patterns authors and translators use for conceptualizing metaphoric mappings. Over the past two decades there has been a significant growth of research interest in metaphor translation (Schäffner, Chilton, 2020; Hong, Rossi, 2021). Given that metaphor is a matter of thought represented by metaphoric expressions in language, translation is viewed as a process of mapping conceptual systems rather than just matching linguistic codes (Maalej, 2008). In this context, translation consists in re-conceptualization of a source language message into a target language conceptual system and this process undergoes “a number of cycles of re-conceptualizations” first mediated by translators and then seized by the target language readers (Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, 2010: 107). In view of the advances in MTS it seems unfair that linguistic synaesthesia still remains almost an unexplored realm with few works speculating about the issue (Strick Lievers, 2016; Smirnova, 2016; Shurma, Chesnokova, 2017).

We bring up several questions for discussion. What research methods are adequate for linguistic synaesthesia? Are the already existing models for metaphor translation fully applicable to synaesthetic metaphors or they need further elaboration? Does translation of synaesthetic metaphors by similes, hypallages or other non-metaphoric sensory figures transform the intended synaesthetic image? What translation strategies ensure a better accessibility to synaesthetic images? These questions seem to have gained little attention until now and thus pose a challenge. Our ambition is to add new linguistic evidence to the study area.

Main part

The purpose of our study is to elicit translation patterns and strategies used for synaesthetic imagery by contrasting synaesthetic metaphors from Russian literary discourse with their English translations. As a necessary part of the study, we see investigation of regularities in cross-modal mappings both in the source language and in translation using frame-based analysis. We go forward with an assumption that metaphor translation analysis will help shed light on the strategies of synaesthetic metaphorization in different languages. This paper is concerned with metaphor translation not from the perspective of linguistic devices and techniques employed but rather from the angle of metaphor understanding, decoding and interpretation.

Materials and methods

We studied synaesthetic metaphors from Russian literary discourse, therefore, when selecting the study material, we took into account cross-modal similarities/differences and directionality of metaphoric transfers. Part of the collection has been generated manually from short stories by I. A. Bunin. The preliminary findings and conclusions were then enhanced by the data from the Parallel Corpora within the Russian National Corpus (RNC). The total number of the extracted data is 326 Russian sensory expressions and 742 English translations where synaesthetic metaphors amount to 40% in Russian and 43% in English. Adjective-noun and verb-noun metaphors were used for the analysis. The focus was on strong synaesthesia when two or more sensory modalities are involved in metaphoric mappings.

In order to clarify the modality of the most intricate sensory words we relied on the methodology offered by D. Lynott and L. Connell (Lynott, Connell, 2009) for rating words according to the degree of their correspondences to a distinct modality. Translation counterparts of the original sensory figures from I. A. Bunin’s texts have been found in three translation versions by different English-speaking translators. Hereinafter we will use acronyms for the three target texts – TT1 (Bunin, 2007), TT2 (Bunin, 1992) and TT3 (Bunin, 1989). The data obtained in the RNC will be labelled accordingly.

Several methods were combined to study cross-modal relations as represented by synaesthetic metaphors in two different languages, i.e. contrastive analysis, the tools offered by Frame Semantics (Fillmore, 1982, 1985; Gawron, 2019) and those developed within the cognitive paradigm of the Descriptive Theory of Translation Studies (Toury, 1995), particularly, the methods and approaches of MTS. When signifying frames, we relied on the online database of MetaNet whose rich repository includes frames and their core/noncore elements, frame-evoking words, conceptual metaphors, metaphor-to-metaphor relations.

Frame-based analysis was incorporated into the study for several reasons: first, it significantly enhances CMT methods by offering relevant tools for a more detailed modelling of metaphoric mappings, second, it is relevant for reconstructing and comparing the intended (the author’s) cognitive strategies and those used by translators when dealing with synaesthetic metaphors. Noteworthily, frame-based analysis now gains attention in sensory language studies (Petersen et al., 2008; Zawisławska et al., 2018; Zawisławska, 2019). As we claimed in Introduction, synaesthetic metaphors emerge from image schemas, pre-conceptual gestalt-like structures, representing image as a whole and hence, hardly susceptible to modelling. Frames are “more elaborate concepts” than image schemas or domains, “…domains are larger, multi-frame entities” (Dancygier, Sweetser, 2014: 23). Thus, frame characteristics, namely, its accessibility for lexical units and its potential to structure larger entities such as domains and be structured into smaller components such as slots, make the frame almost a perfect analytical tool for metaphor studies. Interestingly, in the MetaNet metaphors are defined as source-to-target frame mappings, not domain ones. It means that cross-modal relations in synaesthetic metaphors are frame-structured where each frame of the source domain is projected on the corresponding frame of the target domain. For example, we can reveal synaesthesia in velvety voice by applying frame-based approach: (AUDIAL INPUT←TACTILE INPUT: SOUND TONE ← TEXTURE). Consequently, the activated image schema metaphor HEARING IS TOUCH is the product of source-to-target mapping or “frame shifting” in terms of frame semantics.

Frame-based analysis was applied to modelling mappings underlying synaesthetic metaphors in the source language (SL) and the target language (TL). Frame-based analysis combined with methods of MTS proved efficiency for detecting universals and shifts in understanding inter-modal relations by Russian authors and English-speaking translators and for reasoning causes and effects of such shifts across languages and, what is more, across individuals in cases when the contrastive analysis revealed two or three different translations of the same Russian synaesthetic metaphor.

Results and discussion

Presumably, MTS backed by frame-based analysis can help shed light on the processes underlying understanding, decoding and interpretation of synaesthetic metaphors. This paper is concerned with the strategies translators use when deciding on the appropriate (from their viewpoint) option for a synaesthetic metaphor in a TL.

In the analyzed data there are examples when synaesthesia is fully retained in translation:

(1) ледянаямгла – icy murk (TT2);

(2) тяжелыйтуман – heavy fog (TT1, TT2, TT3, RNC);

(3) теплаячернота – the warm black (TT1); warm blackness (TT3);

(4) неболегкое – the sky is light (TT1);

(5) бархатныеглаза – velvety eyes (RNC).

In all the above expressions the same conceptual metaphor VISION IS TOUCH is further structured according to different patterns. In (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5) TOUCH-VISION metaphors share the same major frame VISUAL INPUT ← TACTILE INPUT, although the sub-frames vary. TOUCH domain in (1) and (3) integrates temperature and visual co-associations (VISIBILITY/COLOR ← TEMPERATURE), while in (2) and (4) it is structured by the WEIGHT component (VISIBILITY←WEIGHT) and in (5) by the TEXTURE sub-frame (SIGHT ← TEXTURE).

Similar mapping conditions in the SL and the TL are realized due to the analogical structures of source / target frames and sub-frames in the original Russian metaphors and their English translations. Synaesthetic metaphors both in the SL and the TL are syntactically and semantically equivalent and share the same directionality of mappings, thus evoking highly similar synaesthetic images. When labelling frames we addressed the MetaNet where SEEING is TOUCHING metaphor is described as a series of mappings between the source frame and the target frame.

Similar mapping inferences occur even in case of frame shifts, though minor ones, in the TL domains:

(6) ледянаямгла – icy fog (TT1);

(7) неболегкое – the sky is ethereal (TT2).

In (1) and (6) we have two slightly different translations of the same Russian metaphor ледянаямгла. Though sharing the same cross-modal mapping pattern, translations in (1) and (6) differ in the frame structures of the target domain (VISION). Murk in (1) is associated with extremely poor visibility, while fog in (6) implies just poor visibility without any extremity. Therefore, it is the INTENSITY sub-component of the source or target domain (or both) that can make a significant difference when translating synaesthetic metaphors. Conceptually similar representations in the SL and the TL vary at the level of sub-categorization due to different INTENSITY inferences in the SL and the TL. INTENSITY becomes critical in (4) and (7) where the source domain is affected. The attributes light and ethereal represent two variations of the same WEIGHT frame structure (small weight vs. almost weightless).

Y. Popova claims that the properties and qualities encoded by adjectives are typically conceptualized “as possessing inherent degrees of intensity”, and thus intensity in the semantics of adjectives “reflects directly one of the most pervasive aspects of experience, namely SCALARITY” (Popova, 2005: 403-404). Variations in translation of the same synaesthetic metaphor can stem from variations in comprehension of scalar representations by different translators. As we can see in the examples above, even minor shifts in frame structures cancel full analogy between the original synaesthetic metaphor and its translation versions, thus in this case we can say about similar mapping conditions, yet resulting in partial verbal-conceptual equivalence.

In case when the repertoire of linguistic means for shaping synaesthesia in a TL differs from that in a SL, we find different synaesthetic transfers in the SL and the TL:

(8) услышишьзапахяблок – notice the scent of apples (TT1);

(9) услышишьзапахяблок – catch the scent of apples (TT2).

In (8) and (9) synaesthesia is preserved in translation, however, the resulting synaesthetic images are different. In (8) HEARING-SMELL synaesthesia is interpreted through VISION-SMELL co-association. In (9) translation relies on TOUCH-SMELL pattern instead of the original HEARING-SMELL synaesthesia. Obviously, the author and the translators exploit different image schemas and, consequently, encode synaesthesia using different lexical means.

Sometimes translator-related factors, i.e. individual translation solutions, bring about shifts in frame structures. Compare:

(10) мелкийтреск (дрожек) – shallow chatter (of a light-running drozhky) (TT1); faint clack of a light drozky (TT2).

Different mapping conditions are revealed in the sub-frame structures of the SL metaphor and the TL translations. The shared major frame component TOUCH/VISION verbally realized in the adjective мелкий is further structured by different sub-frames: HEARING ← SIZE in the SL gives way to HEARING ← DEPTH in TT1 and HEARING ← FORCE in TT2.

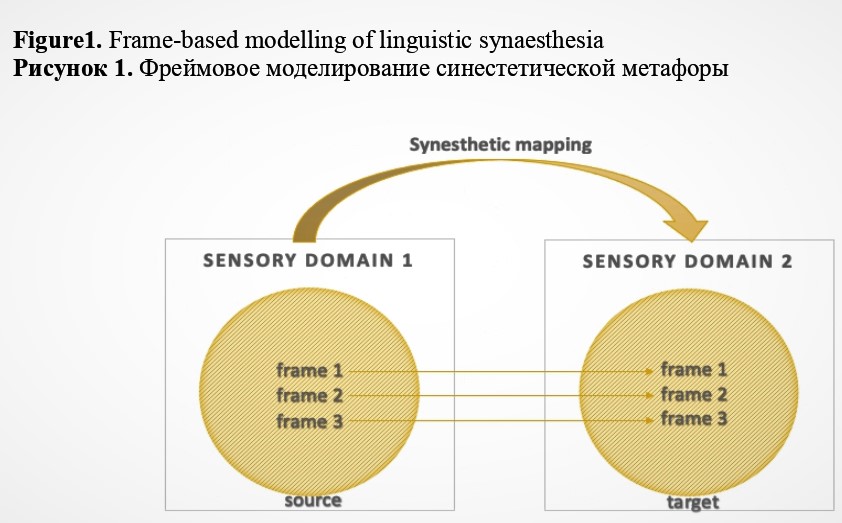

Noteworthily, synaesthesia is preserved in translation only if all the components of one sensory frame structure overlay the components of the other sensory frame structure, which enables cross-modal integration (See Figure1).

Figure1. Frame-based modelling of linguistic synaesthesia

Рисунок 1. Фреймовое моделирование синестетической метафоры

Minor semantic shifts as in (6) and (7) or even synaesthetic substitutions as in (8), (9) and (10) eliminate neither translation equivalence nor synaesthesia.

Synaesthetic effects are lost when an original synaesthetic metaphor is translated into the other, non-synaesthetic, metaphor:

(11) мягкоенебо – vernal clouds (TT2).

The replacement of the intended synaesthetic image with a non-synaesthetic one as in (11) serves as an example of synaesthetic metaphor-to-non-synaesthetic metaphor translation stemming from different mapping conditions. Differences between the original synaesthetic metaphor and its translation counterpart in (11) relate primarily to the source domains’ mismatches. TOUCH is replaced with a SEASON-RELATED frame: “vernal – relating to or occurring in spring; fresh or new like in the spring” (Merriam Webster Online Dictionary). Apparently, the translator changed the intended conceptualization pattern and thereby failed to reproduce synaesthesia: (11) VISUAL INPUT ← TACTILE INPUT (SL) vs. VISUAL INPUT ← SEASON-RELATED KNOWLEDGE (TL). Thus, vernal clouds evokes SEEING is KNOWING metaphor (as it is signified in the MetaNet) rather than VISION is TOUCH.

Translation of synaesthesia by hypallage brings us even further from the intended synaesthetic image. Hypallage implies syntactic and semantic shifts dramatically affecting synaesthesia:

(12) студенаязаря – freezing final glow of dusk (TT1);

(13) студенаязаря – the bitter-cold evening glow (TT2);

(14) тихиеогоньки (семисвечника) – the quiet little red flames (TT1);

(15) бархатныеглаза – soft velvety eyes (RNC).

In (12), (13), (14) and (15) the translators almost destroy the intended synaesthesia by incorporating a complementary attribute or several attributes in translation. This diverts the focus of attention and, as a result, synaesthesia becomes significantly loosened. Reconstruction of frame structures underlying the original metaphors and the hypallages in translation might help trace the routes leading to translation transformations of the intended TOUCH-VISION and HEARING-VISION synaesthetic correspondences. As stated above, synaesthesia is formed by overlaying of source-target frame structures, whereas a hypallage displays quite a different pattern. In a hypallage several successive attributes describe the same referent, and thus synaesthetic connections become significantly loosened. Compare,

(12) and (13): SIGHT ← TEMPERATURE (SL) vs. SIGHT ← TIME ← TEMPERATURE (TL);

(14): SIGHT ← SOUND (SL) vs. SIGHT ← COLOR ← SIZE ← SOUND (TL);

(15): SIGHT ←TEXTURE (SL) vs. SIGHT ←TEXTURE ←DENSITY (TL).

Actually, hypallage is a specific, rather sophisticated sensory figure intertwining closely with synaesthesia, yet it is not synaesthetic in a strong linguistic sense. According to F. Dupeyron-Lafay, due to syntactically broken cross-modal relations, “the synaesthetic conceptual conflict …is therefore a sort of accident” (Dupeyron-Lafay, 2017: 204). Moreover, unidirectionality and asymmetry are in question (e.g., velvety blackness of the night or black velvet of the night – forward or backward direction seems to make no difference). However, in discourse synaesthetic-metaphoric status of hypallage is not entirely cancelled, the reader can subjectively feel inter-modal associations encoded in the adjective-noun part of the hypallage. Interestingly, Russian-English translation of synaesthetic metaphors into hypallages seems to be one of the most preferred translation strategies.

Another translation choice for linguistic synaesthesia is translation into comparison consisting in substitution of the synaesthetic metaphor for the simile or some other comparative structure:

(16) горячаякрасота –handsome in a sort of ardent way (TT2);

(17) притихшиелистья –leaves somehow hushed and submissive (TT2).

Synaesthetic metaphors and comparisons are based on different cognitive patterns – whereas the former employ mechanisms of analogy and involve cross-sensory transfers when one modality is shaped in terms of the other, the latter compare two sensory modalities without undermining the autonomy of the each. With reference to empirical studies, R. de Mendoza and co-authors argue that “open simile offers a much less restricted range of interpretative options than metaphor” (Mendoza, 2014: 304). Thus, translation of synaesthetic metaphors into comparison means full loss of synaesthesia and significant deviations at the lexico-grammatical level.

Noteworthily, this strategy is not frequent though deserves attention, since it is quite a challenge to understand the translation choices in favor of comparisons when the synaesthetic metaphor is seemingly a better alternative. For example:

(18) горячаякрасота – flamboyant good looks (TT1);

(19) притихшиелистья – the garden trees are almost quiet (TT1).

In (16) the intended TOUCH-VISION synaesthesia is destroyed because of the radical structural decomposition, while in (18) the original synaesthetic image is fully preserved. In (17) the translator deletes the intended synaesthesia both syntactically and semantically by adding “somehow” and “submissive” that are apparently redundant in translation of synaesthesia. In (19) the translator clearly demonstrates that synaesthesia is not impossible. Presumably, translation of synaesthetic metaphors into comparison can arise from TL requirements, but in most cases this strategy seems to be the subjective translation choice, and thus loss of synaesthetic effects can hardly be justified.

There are few examples of translation of synaesthetic metaphors into non-metaphors:

(20) густойблаговест – the church bell ring (TT1);

(21) неслисьзвонки – calls rang out (TT1);

(22) полилисьхвалы солнцу – they praised the sun (TT1).

In (20), (21), (22) the intended synaesthesia is fully lost in translation and we tend to account it for the subjective choice of the translator especially in view of the alternative translations retaining the original TOUCH-HEARING synaesthesia:

(23) густойблаговест – viscous peal (of church bells) (TT2);

(24) неслисьзвонки – bell calls raced (TT2);

(25) полилисьхвалы солнцу – they poured out praise to the sun (TT2).

It should be explained why we refer to (21), (22), (24) and (25) as HEARING is TOUCH metaphors. Russian неслись, полились and English raced, pouredout evoke touch-related frames BODY SENSE or KINAESTHESIA that, according to Y. Popova, structure TOUCH domain alongside PRESSURE, TEMPERATURE, WEIGHT, TEXTURE, HAPTICS (Popova, 2005). Actually, TOUCH is the most productive source domain for synaesthetic mappings presumably due to its well-developed frame structure. Tactile experiences shape a variety of sensations and these sensations are “continuous, sequential and non-discrete” (Popova, 2005: 409), they are relative and subjective as compared to visual sensations that are discrete, simultaneous and more universal.

There are few and therefore valuable examples where the translator uses a metaphor, however, it is not present in the original:

(26) темнеет – full dark falls (TT1).

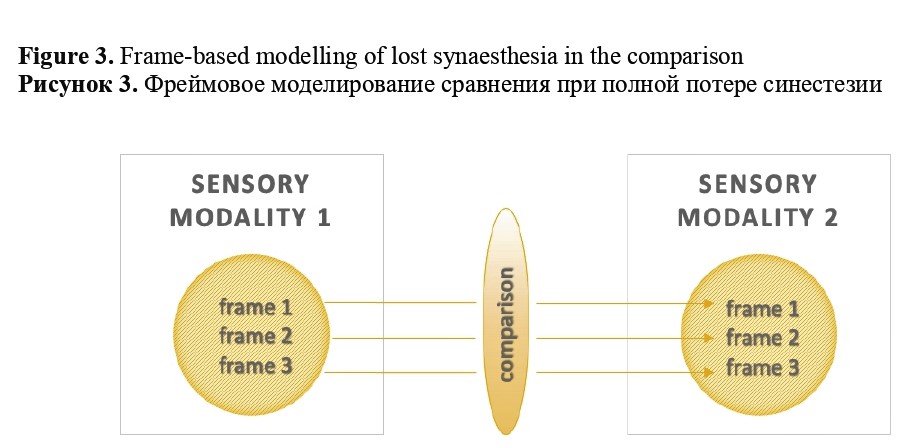

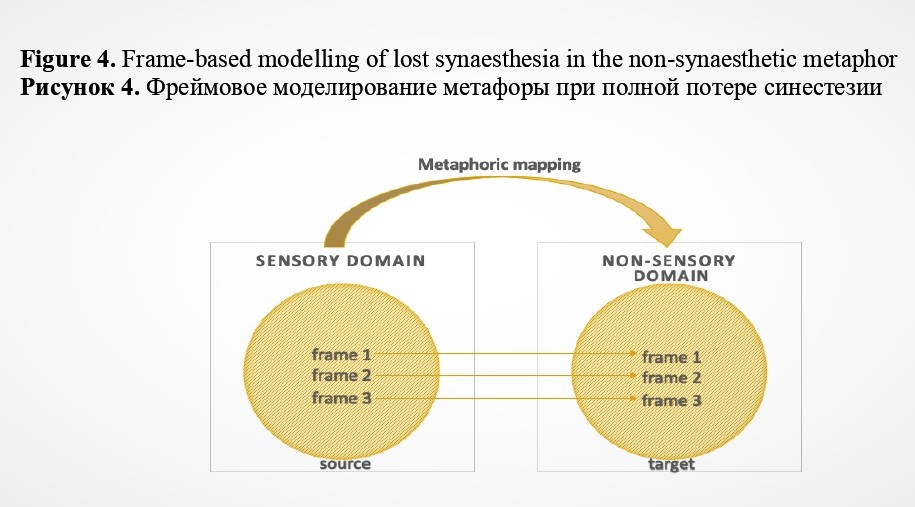

Loss of synaesthesia in translation results either from misleading translation strategies or from TL constraints. Consequently, omissions and substitutions of the original sensory words or syntactic transformations lead to loosening (in metaphor-to-hypallage translation) or deleting (in metaphor-to-comparison or synaesthesia-into-a non-synaesthetic metaphor translation) synaesthetic effects both at verbal and conceptual levels (See Figures 2-4).

Figure 2. Frame-based modelling of loosened synaesthesia in the Hypallage

Рисунок 2. Фреймовое моделирование гипаллаги с ослабленными межмодальными связями

Figure 3. Frame-based modelling of lost synaesthesia in the comparison

Рисунок 3. Фреймовое моделирование сравнения при полной потере синестезии

Figure 4. Frame-based modelling of lost synaesthesia in the non-synaesthetic metaphor

Рисунок 4. Фреймовое моделирование метафоры при полной потере синестезии

Synaesthesia is rather a sensitive perceptual-linguistic operation, and thus must be treated accordingly: any significant semantic or syntactic shifts in translation will inevitably bring about critical changes in the intended frame structure underlying cross-sensory blendings within the image schema.

Basing on the research findings and relying on the linguistic evidence of MTS we want to share our understanding of the major translation strategies as far as synaesthetic metaphors are concerned. Before focusing on translation patterns used for synaesthetic metaphors, it is necessary to briefly outline the evolution of metaphor translation models that obviously set the ground for further adaptation and extension with regard to translation of synaesthetic metaphors.

G. Toury pioneered Descriptive Translation studies and offered his vision of metaphor translation process as based on source-target texts comparison rather than on the primacy of the source text, the latter approach was a widely recognized concept in Translation Studies at that time. He offered six solutions for metaphor translation: 1) literal translation; 2) substitution; 3) paraphrase; 4) metaphor into 0; 5) non-metaphor into metaphor; 6) 0 into metaphor (Toury, 1995).

With a cognitive turn in MTS the focus shifted from searching for linguistic solutions towards modeling cognitive scenarios in metaphor translation. As a powerful impetus for investigating in this direction served the hypothesis of N. Mandelblit who suggested two possible paths in metaphor translation:

1) similar mapping conditions (SMC), where the linguistic expressions in the SL and TL reflect the same mapping patterns, and thus have the same underlying conceptual metaphors;

2) different mapping conditions (DMC), where original metaphors and those in translation differ both linguistically and conceptually, which gives rise to different conceptual metaphors in two languages (Mandelblit, 1995).

An extended version of N. Mandelblit’s hypothetical model comprises linguistic-conceptual comparison and includes one more pattern of metaphor translation:

1) SMC with similar verbal metaphors in the SL and the TL (metaphor-to-the-same-metaphor translation);

2) SMC with different linguistic realization (M1-M2);

3) DMC (Al-Hasnawi, 2007). According to the author, the first pattern covers universal SL metaphors rooted in a shared human experience, the second one encompasses conceptual metaphors that have counterparts in the TL but are lexicalized differently, and the third pattern is applicable to culture-bound metaphors that exhibit culturally unique cross-domain mappings and thus, hardly find counterparts (conceptual and lexical) in the target language (ibid.). However, such hypothetical models are rightly criticized for being based on theoretical assumptions rather than on authentic linguistic data, which inevitably “turns metaphor translation into a metaphor-substitution game where translators endeavor to achieve optimal mapping both at surface level and conceptual level” (Hong, Rossi, 2021: 20). With this caution in mind, we addressed the literary discourse and enhanced the conventional comparative study with frame-based analysis.

As stated above, synaesthetic metaphors have peculiar structure (image schema metaphors framing cross-sensory transfers), therefore, the outlined metaphor translation patterns need some further elaboration to match linguistic synaesthesia. With few works engaged with translation of synaesthesia, we hope our study will fill the gap and shed light on the strategies exploited by translators when confronted with linguistic synaesthesia. The findings enabled us to elicit eight major translation patterns and strategies:

1) SMC with fully retained synaesthesia in the TL and full lexico-grammatical equivalence (SM-SMf/e);

2) SMC with retained synaesthesia though with minor frame shifts in the image schema in the TL and with minor (if any) lexico-grammatical changes, and thus resulting in partial verbal-conceptual equivalence (SM-SMp/e);

3) DMC consisting in the replacement of the original synaesthetic image with a different synaesthetic image in the TL when two different synaesthetic metaphors are activated (SM1-SM2);

4) DMC consisting in the replacement of the original synaesthetic image with a different, non-synaesthetic, image in the TL with two different conceptual metaphors activated (SM-NSM);

5) translation into hypallage resulting in a loosened synaesthetic effect and deviations at lexical and grammatical levels (SM-Hypallage);

6) translation into comparison leading to a full loss of the original synaesthesia and deviations at a lexico-grammatical level (SM-Comparison);

7) translation of a synaesthetic metaphor into a non-metaphor (SM-NM);

8) translation of a non-metaphor into a synaesthetic metaphor (NM-SM).

This typology results from an attempt to reconcile linguistic methods, frame-based analysis and tools of MTS. We borrowed the term “mapping conditions” from MTS to talk exclusively about metaphor-to-metaphor translations; when it comes to translation of synaesthesia, we can talk about “similar mapping conditions” and “different mapping conditions”. SMC mean full or partial (with minor semantic shifts) equivalence in interpretations of the intended synaesthesia, DMC mean transformation of the intended synaesthesia by addressing a different conceptual metaphor, either synaesthetic or non-synaesthetic. Significant syntactic-semantic transformations in translation of synaesthesia apparently split the intended cross-modal correspondences by affecting dramatically the intended order of source-to-target projection patterns where two sensory frame structures are engaged.

Conclusions

The study has made it utterly clear that linguistic synaesthesia definitely poses a number of scientific challenges, thereby inspiring great scientific insights. Actually, synaesthesia, which is a perceptual-conceptual-verbal phenomenon, requires a multifaceted approach. The combination of methods and tools developed within CMT, Frame Semantics and Metaphor Translation Studies has proved its efficiency for understanding and explaining cross-modal inferences in the SL and the TL. CMT formulated theoretical fundamentals of metaphoric conceptualization, which set the ground for distinguishing the synaesthetic metaphor as a specific conceptual metaphor type; Frame Semantics equipped us with methods and procedures for analyzing linguistic synaesthesia from the cognitive perspective; Metaphor Translation Studies gave clues for developing typology of translation patterns and strategies exploited for synaesthetic expressions. We should note that incorporation of the three approaches in sensory language studies is a novel experience and, hopefully, it will contribute to the multidisciplinary research of synaesthesia.

The study has demonstrated the diversity of the strategies used for translation of synaesthetic metaphors. The translator’s toolkit offers a number of solutions ranging from highly accurate reproduction of the intended synaesthesia to a full loss of inter-modality when Russian synaesthetic metaphors are translated into hypallages, comparisons and non-metaphors. As a matter of fact, in most cases synaesthesia is preserved in translation, this is true at least for creative synaesthetic metaphors that can be found in literary discourse. Synaesthetic shifts or even omission of synaesthesia can stem from conceptual-cultural-verbal mismatches between the SL and the TL, which is virtually unavoidable. However, it is often the translator, who makes a choice in favor of or against synaesthesia.

Our typology of patterns and strategies used for translation of linguistic synaesthesia includes eight major types. We significantly revised the already existing typologies by adapting them to the study subject and added new strategies that have never been described in Metaphor Translation Studies, yet they are quite relevant for translation of synaesthetic metaphors. First, we elicited SM-SMf/e, SM-SMp/e, SM1-SM2 translation strategies that are specifically consistent with linguistic synaesthesia. Second, we drew a line between SM1-SM2 and SM-NSM translations taking into account different metaphoric patterns in the SL and the TL. Third, we elicited two more strategies (SM-Hypallage and SM-Comparison) that either loosen or destroy synaesthesia syntactically and therefore, conceptually. It should be emphasized that all our assumptions and speculations are not barely hypothetical, we build argument basing on frame-based analysis which proved its efficiency in cognitive science.

In conclusion, our main ambition is to add new data to sensory language research where a number of scholars come together to build a consistent theory of linguistic synaesthesia. Much has been done, yet much remains to be done. There are several routes for further investigations:

1) the cognitive mechanisms triggering inter-modal associations, i.e. analogy or congruity, are still highly debatable, and thus need clarification;

2) verb-noun and noun-noun synaesthetic expressions are unfairly overlooked, however, they exhibit specific cross-sensory blendings and thus, must gain as much attention as adjective-noun models;

3) lack of works discussing typology of sensory figures hampers attempts to qualify such words as смоляной – tar-black that apparently exhibit some features of synaesthesia;

4) insufficiency of empirical data encourages efforts from psychologists and psycholinguists. Truly, synaesthesia seems a highly challenging, yet highly promising study area.

Corpus materials

Bunin, I. A. (1965-1967). Sobranie sochineniiv 9-ti tomakh pod obshchei redaktsiei A. S. Miasnikova, V. S. Riurikova, A. T. Tvardovskogo [Collected works in 9 volumes edited by A. S. Miasnikov, V. S. Riurikov, A. T. Tvardovski], Khudozhestvennaia literatura, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Bunin, I. A. (1989). Wolves and other love stories (translated into English by Mark Scott), Carpa Press, Santa Barbara, California, USA. (In English)

Bunin, I. A. (1992). Night of denial. Stories and novellas(translated by Robert Bowie), Northwestern University Press Evanston, Illinois, USA. (In English)

Bunin, I. A. (2007). Collected stories(translated into English by Graham Hettlinger), Chicago, USA. (In English)

Список литературы

Список использованной литературы появится позже.