Цифровые и национальные домены: тенденции ономастики в интернет-коммуникации

Aннотация

Подобно тому, как в реальном физическом пространстве присутствуют названия зданий, вывески и адреса, уличная реклама и дорожные знаки, виртуальное пространство наполнено названиями веб-сайтов и доменными именами, образующими виртуальный лингвистический ландшафт. В данной исследовательской работе представлен анализ системы именования доменов в Интернете, в частности исследование числовых доменных имен и национальных доменов. В интернет-пространстве могут использоваться знаки и символы из разных семиотических систем, что делает эту область особенно интересной для современных лингвистических исследований. Более того, использование иероглифических и цифровых доменных имен в китайском интернет-пространстве становится определённым трендом, отражая культурные и технологические особенности региона. С этой точки зрения китайские доменные имена стали естественным связующим звеном между интернет-технологиями, китайской традиционной культурой, современными и традиционными производствами. Материалом исследования являются доменные имена интернет-сайтов. Целью нашего исследования выступило описание стратегии развития иероглифических и числовых доменных имен. Актуальность исследования определена малой изученностью ономастики виртуальных реалий. Доменные имена служат идентификаторами и средством коммуникации. Важно помнить, что доменное имя – это динамичное явление, а тенденции в области именования доменов могут со временем меняться. Кроме того, ценность доменного имени часто субъективна и зависит от таких факторов, как узнаваемость бренда, запоминаемость и рыночный спрос. В ходе исследования выявлены тенденции интернет-ономастики доменных имен, в частности, использование иероглифов и числовых кодов. Особое внимание уделяется доменным именам, в создании которых проявляется творческая функция языка.

Ключевые слова: Интернет-дискурс, Интернет-коммуникация, Интернет-лингвистика, Интернет-ономастика, Ономастика, Доменное имя, Иероглифический домен, Цифровой домен, Китайский язык

К сожалению, текст статьи доступен только на Английском

Introduction

The Internet space, inherently dominated by the organization of digits, has in recent years become a battleground for Latin, Cyrillic, and ideographic scripts. Since the birth of the Internet, due to objective reasons, the development of information products has followed a path of anglicization, and for a long time, domain names were represented solely by Latin letters and sometimes by numbers. However, the situation is changing.

Much of this change is associated with the development of alternative IT giants in countries where English is not the native language, such as Korea and China. Furthermore, multilingualism on the Internet ensures that language does not become a barrier to accessing the benefits of humanity. Indeed, the desire of nations to assert their sovereignty in virtual space becomes increasingly evident. D.S. Barinova notes that “the level of development of the national domain zone and how it is used by the state, business, and society can serve as an indicator of the development and effectiveness of the state” (Barinova, 2010, 308). Thus, over time, Cyrillic and ideographic characters appear in the domain system, and the use of different systems on the Internet emphasizes the multipolarity of political and social attitudes. On the other hand, the desire of countries to use their national language signifies an aspiration to emphasize informational sovereignty. Moreover, there exist a number of organizations and language activism movement, such as a long-standing research project The IDN World Report[1] that believe that international domain names contribute to linguistic diversity online. Their aim is to enable users to navigate the Internet in their native language, promote multilingualism and universal access to cyberspace.

This trajectory of domain name development and the states’ determination to defend their sovereignty and interests in the Internet space highlight the relevance of researching this direction, so as O. V. Dedova and M. S. Kuprienko state, the name takes on the role of a beacon, a navigator in the online world, a landmark in electronic information space (Dedova, Kuprienko, 2013: 63). Moreover, the phenomenon of creativity in creating domain names remains a relatively understudied area of linguistics, particularly domain names registered in non-Latin scripts, known as internationalized domain names. For example, as Yu. E. Polyak carried research on internationalized Cyrillic domains, he mentioned several reasons why new domain names with native language characters can be popular. The researcher pointed out that when a new domain zone emerges, many ‘tasty’ names appear that were previously occupied – names of goods, proper names, geographical concepts etc. In addition, using native language makes it possible accurately and unambiguously indicate objects (Polyak, 2018: 116). Indeed, up to now, far too little attention has been paid to domain names in general and to certain peculiarities in such countries as China, where giant technology companies and vast Internet market give insights into the key global trends. Thus, this paper attempts to contribute to Internet onomastics research as well as to address the issue of hieroglyphic and numeric domain names.

Methods and materials of the study

The use of national languages is mostly discussed relating to the localization of websites, where navigation sections and site content are adapted to the national-cultural specificity of users. However, researchers have recently addressed issues of the status and naming of domain names, as well as linguistic creativity and innovations in domain naming. Many of these works have served as a theoretical basis for our research, that is to say, study on phenomena of Internet communication (Khazova, 2023); research on main trends, problems and selection mechanisms of domain names (Zhiltsov, 2020); study on the development of different domain systems, including works on cyberspace management systems (specifically related to domain names and IP addresses) (Kalyatin, 2002; Zakalkin, 2022); study on the development of onomastic space of the Internet (Kersten, Lotze, 2022; Suprun, 2004); examination of the names of websites as a special phenomenon in Internet onomastics (Zubareva, 2021b); research on domain names as identifiers and means of communication (Rozhkova, 2015); study on domain name and name of the file as innovative forms of text names produced by Internet technology (Dedova, Kuprienko, 2013); analysis of linguostylistic means for creating domain names (Kuprienko, 2010); research on domain name as a unit for constructing and identifying the network landscape of the online space, a unit which forms its structure and allows some of its parts to function as microsystems, creating entire ecosystems (Ryabchenko, 2016). Furthermore, domain spaces have started to be studied as separate communities. M. Z. Abdullaeva’s work investigates the spiritual role of Islamic media space of domain ‘UZ’ (Abdullaeva, 2020); L. N. Dukhanina and A. A. Maksimenko conduct an analysis of the network oncological discourse of a three-year retrospective in the top-level domain ‘RU’ (Dukhanina, Maksimenko, 2020). These articles prove the fact that while conducting the research in virtual space it is reasonable to take into account geolocation, analysis of sources and distribution platforms.

In our view, there is a need to outline another research direction, namely, the study of ideographic and numeric domains as onomastic units of the Internet space. This prospective study was designed to investigate current trends in naming numeric and ideographic domains, and to consider linguistic means that are used to make domain name unique and memorable. To achieve this goal, several tasks need to be addressed. Firstly, consider the role of the domain name in creating a sovereign Internet. Secondly, examine the domain as an object of linguistic research. Thirdly, identify the characteristics and trends in the formation of numeric and Chinese-character domains as the brightest examples. The fundamentally new aspect is the consideration of ideographic and numeric domains as unique objects of network naming, as in some cases, domain names represent a fundamentally new phenomenon in onomastics, rather than simply duplicating offline onyms. The practical significance of the study lies in the fact that the obtained data can be in demand in the analysis of the linguistic development of Internet space and the development of marketing strategies.

The material for the study is based on the findings of theoretical research, providing an overview of Internet onyms and the development of onomastics in Internet discourse. Additionally, it is important to note that the material selection is not limited to publications in the Russian language. We made an attempt to analyze materials in English and Chinese.

As for linguistic material, more than 50 domain names were selected. Most of the examples are given from the Chinese Internet zone, though certain trends are exemplified by a few examples from other domain zones. The choice is motivated by the increasing number of numeric and character domains in the Chinese internet space and their growing significance. The employed research methods involve analyzing and synthesizing theoretical and practical material, classifying examples chosen for analysis, and describing the obtained data. The selected domain names were categorized based on specific criteria to facilitate analysis and interpretation. The data obtained from the analysis were described to provide a comprehensive understanding of the observed trends and patterns in the selected domain names. The inclusion of multiple languages in the analysis reflects the global nature of Internet communication and the growing significance of such domains in the Chinese Internet space.

Domain as a toponym in the virtual linguistic landscape

The study of domain names reveals the need to understand the mechanisms of Internet onomastics. Similar to how physical space is surrounded by buildings, signs, and addresses, virtual space is surrounded by website names, nicknames, domain names. What and how we see largely depends on browser design, our settings and permissions, including cookies, content, and website design.

Toponymy of virtual landscape is a relatively new field of study. According to N. A. Ryabchenko, “domain is a part of the online space, forming its structure and at the same time allowing parts of this space to function as a microsystem, creating entire ecosystems in which users are provided with the necessary functioning capabilities and access to information” (Ryabchenko, 2016: 99). Thus, domain names are a kind of toponym in the virtual Internet space, participating in the construction of virtual reality. As V. I. Suprun writes, all information on the Internet is built on an onomastic axis and proper names permeate all texts. Onyms to be studied are the names of functioning parts and units within the Network (cit. ex: Virtual onyms in the Italian Internet environment[2], 2017: 18).

We share L. P. Son’s opinion that “electronic onomastics can become one of its (Internet communication culture) ‘building blocks’, as the harmony of form and content (the concept of the sender and recipient) of an electronic proper name is culture itself” (Son, 2009: 221). Within onomastic studies, questions have been raised about the names of participants in virtual communication or anthroponyms, ergonyms, and pragmatonyms in Internet communication (Zubareva, 2021b; Son, 2009; Son, 2012). However, when it comes to anthroponyms in Internet communication, researchers often conclude that “participants wear masks” (Son, 2009: 218). On the other hand, onomastics of domain names implies different principles of functioning. As noted by A. V. Zubareva, proper names must possess such qualities as uniqueness and attractiveness (Zubareva, 2021a: 101). Meanwhile, the domain name identifies the owner, the goods. Many argue that it serves as a means of communication, a means of information exchange. So, M. Rozhkova concludes that domain names in addition to the technical function of addressing on the Internet and virtual identification began to contribute to the identification of goods, works, services of some producers, sellers and performers among similar goods, works and services “in reality” (Rozhkova, 2015: 62).

Virtual space is an environment for constructing a virtual identity. As A. V. Zubareva notes, the onomasticon of Internet communication is formed in accordance with the logic of the interaction between online (Internet environment) and offline (the familiar “real” world) (Zubareva, 2021b: 122). We cannot but admit that partly domain naming trends are taken from physical reality. For example, in the Russian Internet space, domain names with automobile region codes corresponding to Russian regions can be found, such as 66.ru (Yekaterinburg platform), 161.ru (Rostov-on-Don platform). In addition, the site 66.мвд.рф belongs to the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for the Sverdlovsk Region. To decode why exactly these numbers are used the Internet user is supposed to know automobile codes of Russian regions. Furthermore, domain names 8848.ru (The Vertical Film Festival) and 8848-altitude.ru (a ski clothing brand) refer to Mount Everest's peak. These examples confirm the opinion that the involvement of cultural data allows us to reveal the content and meaning of onyms (including Internet onyms) relying on the interaction of proper names and the culture of the people (Madieva, Suprun, 2017: 38).

We conclude that a domain name is a toponym in virtual space. They are grouped “zonally”, either geographically/regionally (ru, 中国) or used by certain communities and organizations (com, net, info). When classifying domain names, they are often categorized based on their affiliation with a particular zone, national identity, or a field of use. Because of this, there is a need to understand new onomastic phenomena and the mechanisms through which they arose.

Domain name as a part of sovereign Internet

In order to understand why national and numeric domains are of great interest, the section below provides a brief overview of domain naming as an issue of concern for national security. Today, the Internet space becomes not only a zone of interaction but also a platform for asserting interests, propaganda, and lobbying. P. V. Zakalkin emphasizes that the control of cyberspace is largely monopolized by the United States, with other countries being mere consumers and thus susceptible to destructive influence. Therefore, for countries like Russia and China, aiming to assert their positions globally, defending their interests in the Internet environment is crucial (Ignatov, 2022; Gabdrakhmanova, Mahmutov, 2018; Shirin, 2014). Language plays a key role in this, with Cyrillic and ideographic scripts trying to find their place in Internet communication (Zakalkin, 2022).

Currently, there are national domains worldwide. According to a report (Internet Tendencies[3], 2021), domain RU ranks 8th and domain CN ranks 2nd among top-level domains. In Russia there is even a special project for developing an ecosystem for supporting domain names and postal addresses in national languages, primarily in the Cyrillic domain “РФ”[4]. The development of the global domain space is closely linked to the creation of domains in national languages (IDN TLDs)[5]. According to a report (Internet Tendencies, 2021)1, there are a total of 156 IDN top-level domains worldwide, with the highest number using Chinese characters (56), followed by domains using the Arabic alphabet (33), and Cyrillic domains (17). The most demanded IDN top-level domain is .中國 with 1.8 million domain names. China has contributed a lot into development of Chinese-character domains. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has issued the “The14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Information and Communication Industry”[6], that purposes to improve Chinese domain name application environment and to further promote the development and application of Chinese domain names.

S. Couture and S. Topin, discussing sovereignty, note that Russia and China insist on implementing state sovereignty on the Internet. They suggest that the development of Cyrillic and ideographic domain names is an attempt to realize digital sovereignty and resist the hegemony of the Latin and English-speaking world (Couture, Topin, 2020). However, the main restraining factor for the development of Cyrillic and Chinese-character domains is the low level of universal acceptance of such domain names and, above all, difficulties with using email addresses written in national alphabet characters.

Domain name as an object of linguistic analysis

In addition to its potential for political influence, a domain name holds commercial value, and linguistic creativity plays a crucial role in domain naming. It is already universally acknowledged that “domain names used specifically for commercial purposes become a generic identifier of goods (works, services) – like a trademark, an indication of the place of production/origin of products, a universal barcode, etc” (Rozhkova, 2015: 62). A domain name has a complex structure, including several levels: top-level, second-level, and subdomains. Concerning top-level domains, A. V. Zubareva mentions the possibility of playing with first-level domain names. For example, using .NET can create a provocative and humorous effect and even influence offline onomastics. The domain .ME (Montenegro) has undergone commercialization and is used for personal blogs and socially oriented sites. In addition, domain .AI (Anguilla) has become extremely popular in 2023.[7] Undoubtfully, the reason is the growing popularity of artificial intelligence and the continuous discussions of this topic in the media and social networks. Moreover, numeric domain names can also be combined with specific domain extensions (e.g., .com, .net, .org) to create unique combinations.

A. V. Kuznetsov suggests that some domain names can be considered a type of advertising text. Analyzing the linguistic features of German domain names, the researcher has revealed language play types such as the formation of neologisms, violation of language norms, use of colloquial word forms, substitution of letter combinations with numbers, stylization to foreign words, and the use of phonetic spelling (Kuznetsov, 2012). Using these means of language games helps to create novel and memorable domain names. Similar trends can be observed in the context of domain naming in other countries. Historically, domain names were created using Latin letters and numbers. Creating a domain name is limited by certain rules, such as the absence of spaces. On the other hand, a unique and user-friendly domain name needs to be created to distinguish a website from others and make it stand out for users and search engines. Thus, D. A. Zhiltsov claims that naming should correspond to the chosen general marketing strategy and be based on basic naming principles developed by Internet marketers, webmasters, site optimizers, and other digital marketing specialists over the years. The author provides several recommendations, including not to register Cyrillic domains (Zhiltsov, 2020). However, Chinese researchers convinced that native language domain names are not only easy to remember, but also easily promote and disseminate information, have a prominent native language image, which demonstrates cultural confidence. They can also create a safer and more trustworthy Internet environment for Internet users and improve international cyberspace governance on the Internet (Ke, 2020: 166).

O. V. Dedova and M. S. Kuprienko emphasize that “on the modern Internet, the domain name is a key component of hypertext navigation and composition.” Their research reports that site traffic directly depends on the memorability and reproducibility of the domain name. Indeed, domain name becomes a mnemonic tool, reflecting the specifics of the information posted on the site, and also an element of advertising. In view of this, the researchers believe that the main strategy for increasing the effectiveness of a domain name is determined by its relevance with meaningful linguistic units, which can be achieved in various ways” (Dedova, Kuprienko, 2013: 65). On the other hand, A. V. Zubareva notes that Internet environment incorporates traditional onyms, and this process can involve the simple transfer of existing onyms into Internet communication and the creation of new proper names for virtualized objects. She emphasizes the significant influence of programming practices on domain naming trends, such as the absence of spaces, the use of underscores, and the use of uppercase letters.

Furthermore, M. S. Kuprienko mentions that “a modern domain name is intended to be not only an element of navigation, but also a mnemonic device reflecting the specifics of the information posted on the site, and an element of advertising (the site itself, the goods, services offered” (Kuprienko, 2010: 80). The author points out several ways how domain name may be formed: the domain name matches the site title or part of it, the website theme is taken as the domain name, the domain name is taken to be a word that is a hyponym in relation to the nomination site header, the domain name is formed by combining fragments of the site header, the domain was created by truncating the site name or one of its keywords, abbreviation, disabbreviation. There are also a lot of means of language game that help to make the domain name unique, i.e. the use of Latin letters that match the Russian ones, playing on the homonymy of the final part of the domain name (the so-called top-level domain, whose name is written after the dot), replacing a word or part of a word with a letter or number (Kuprienko, 2010).

Meanwhile, M. Yu. Karpenko introduces a new term siteonym and clarifies what exactly should be classified as siteonyms. According to the researcher, firstly, these are names, that users find in the address bar (for example, www.google.com), secondly, the title, that users see on the main page (Karpenko, 2012). Furthermore, Karpenko investigates the motives of nomination of websites, mainly domain names, and classifies them into essential, qualitative, locative, temporal, possessive, patronymic, memorial, ideological, symbolic, associative, nominal, situational domain names. According to the research, siteonyms with essential motivation have a significant advantage. This may be due to the fact that the site creators, in order to increase the number of potential visitors, already start with the domain name and site name, and advertise its content or functions (Karpenko, 2014). Subsequently, the study of siteonyms was continued in the works that mention siteonyms as a type of ideonyms (Chaykisova, 2017), that examine cultural and linguistic aspects of German siteonyms (Daldinova, Bardaeva, 2021; Daldinova, Buraeva, 2023; Filimonenko, 2023). These articles contribute a lot to the research of linguistic point of view. Though we believe that it is not right to examine domain names and titles of the sites as similar objects. The reason is that different means and strategies are employed to create these onyms, for example, there are certain technical restrictions, i.e. titles of the site can use different graphical styles and colors, while structure, length, use of special characters and punctuation marks in domain naming have some peculiarities. Moreover, when national top-level domain in Russia was discussed, it was decided to choose. РФ but not “py”. The reason is that domain “ру” written with Cyrillic letters resembles domain of Paraguay (“py”) written with Latin letters. Thus, instead there is Cyrillic domain “рус”.

In summary, linguistic analysis of domain names reveals the creativity involved in their nomination, influenced by both commercial and linguistic considerations. The use of language play, adherence to marketing strategies and cultural aspects, contribute to the linguistic landscape of domain names.

Linguistic analysis of numeric and Chinese-character domain names

The analysis of Chinese data confirms one of the obvious peculiarities of the Chinese Internet space – the appeal to characters and numbers. And if character domains are a phenomenon of the last few years, then digital domains have appeared a long time ago. This is due to several reasons. Firstly, the figures are very close and understandable to the Chinese. As Zhu Guiwen notes the Chinese are accustomed to operating with numbers and using numbers to create onyms. Even e-mails most often consist of numbers rather than letters. (Zhu, 2014: 43). Secondly, the Chinese put a certain meaning into the numbers (Akhrenova, Dubinina, 2022; Han, 2022). Moving on to the consideration of numeric domains, in the contemporary Internet space in China, numbers continue to play a crucial role, especially in digital onomastics. Currently, around 9 million domain names consist solely of digits, accounting for over 3% of the total number of domains. Here are some findings from the research conducted by Domains Index on digital domains[8]: there is an increasing number of digital domains, the quantity of digital domains in new domain zones surpasses that in old ones; the highest number of digital domains is found in the COM zone, among national zones China (.cn) leads in the number of digital domains; popular domains typically consist of 3-4 digits, with the longest domains having 63 digits. As for numeric domain name’s structure, there can be found repeating numbers, that are often considered memorable; sequential numbers, that are popular for their simplicity; lucky numbers, that is numeric combinations that are considered lucky in various cultures, such as 888 in Chinese culture; premium numbers, that are considered premium, and businesses may be willing to pay a higher price for them; year-based numbers. Numbers can also be combined with letters.

The numbers in Internet communication can be considered as a kind of code, and decoding them is possible only with the information based on the speaker’s culture and language, as they have national and linguistic identity (Dubinina, 2022: 26). Furthermore, An Zhiwei claims that digits have sociocultural meaning, and in China this effect is mostly based on homonymy (An, 2002).

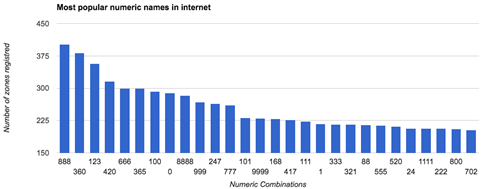

Figure 1. The chart of most popular numeric domain names

Рисунок 1. Таблица самых популярных числовых доменных имен

Meanwhile, similar trend of popularizing numeric domains can be found not only in China. According to the chart of most popular numeric names1 (Figure 1), the most popular combination is 888 and it is registered in 402 domain zones. It turns out, that in different cultures it has different meaning quite often positive, including “eternity”, “limitless potential”, “power”, “success”, “prosperity” etc. As for China, the number 8 has gained success, because it is homophonic with “发”, that means to make a fortune. For example, a digital lottery trading platform uses 8791.com domain, that encourages users to get rich (加油发财). The second most popular combination 360 conveys a message of “harmony”, “integrity” etc. For example, domain 360.cn is used for security software pointing out the importance of complex safety, domain 360.yandex.ru is used for a set of services for solving every day and work problems.

Researcher Xiang Xuehua from the University of Illinois focuses on studying the linguistic and cultural characteristics of the domain names of the top fifty most-visited websites in the US and China. The researcher uses several criteria such as brevity of a domain, sound and rhythm, recourse to semiotic systems, intertextuality. She comes to the conclusion that Chinese domain names are heterogeneous, mixing semiotic systems and featuring more cultural symbolism (particularly number symbolism) and literary intertextuality (Xiang, 2012). Indeed, in China numbers not only represent mathematical concepts but also carry symbolic meanings and hold magical significance. And the abundance of homophones has led to the development of imagery and symbolism in thinking and speech. Chinese people don’t like some digits, such as 4, because it is a homophone for “death”. What is more, there are some regional peculiarities. In the north, 2 is a curse and means stupid. Some people also suggest that the best numbers are 5 and 9, because 9 is the most perfect number among single digits, 9 is the highest, and 5 is in the middle. In addition, in China number 6 is a very auspicious number, which means good luck and success.[9] For example, 6.cn, also known as 六间房 (6 rooms), is one of the online video entertainment live broadcast platforms, providing 24-hour uninterrupted video live broadcast service. It is believed that from the perspective of traditional Chinese culture, “6 rooms” is the most auspicious combination which means good luck and happiness.[10] Moreover, 6 is also homophonic with 流 which means a stream, thus pointing to specialization of the platform.

Using digital code in China is a peculiar feature of domain naming. On the other hand, though numeric virtual onomastics is rather widespread, it is not always possible to unambiguously interpret these combinations. There are some mostly common phrases that can be relatively easy identified: 51=我要, 520=我爱你, 518=我要发etc. (Fu, 2013). However, homonymy allows to interpret numbers in different ways, and many works that examine digits and combination of digits as part of Internet user’s communication admit that digits can correlate with different words (Zhou, 2003). For instance, a leather goods store 哇咕哇咕 is located at the website 51wagu.com, where 51 can be deciphered as 我要 (I want). The same code is used in creating 51tt.com.cn (淘陶网) for a real estate and home furnishing website, 51dhw.com.cn (51订货网) for electronic business platform, a phone number and domain name 4008-517-517.com for McDonald’s take away and delivery, and 517 can be deciphered as我要吃 (I want to eat). Furthermore, the domain name 51job.com for platform that provides individuals with job recruitment information and enterprises with a full range of human resources services can be deciphered as “I want a job”. On the other hand, the platform is also known as前程无忧 (a worry-free future), and 51 can be found homophonic with 无忧 (worry-free).

Let us introduce some more examples. A store for children and mothers 麦乐购 is located at the website M6go.com, where the number 6 is homophonous with the ideograph 乐. The domain name 2797.com for ticketing platform can be deciphered as爱去就去[11] (if you want to go, then go). The online store 1 药 网 is located at the website 111.com. The use of the number 1 in the domain name may be related to the name where the digit one is also used, and the original name of the online store was 1 号药店. On the other hand, the digit 1 may have the reading yāo, which is homophonous with the reading of the word medicine 药 (yào), also found in the name, creating certain associations with medicine for users. The other example is domain 91.cn, that was created for professional health information portal. It is homophonic with the phrase就医, which means to receive medical treatment. Another well-known example is the Alibaba Wholesaler Network at the website 1688.com. The numbers 1688 are homophonous with the company’s name 阿里巴巴 (ā lǐ bā bā)

The Chinese domain name also refers to a domain names that contain Chinese characters. We share the viewpoint that the use of Chinese characters produces a form of “localised” Internet, rather than a separate Internet (Arsène, 2015). Examples include domain names like 新华网.cn (XinhuaNet.cn) containing Chinese characters, as well as internationalized country and region top-level domain names containing Chinese characters such as .中国 (.China) and.广东 (.Guangdong). It also includes generic Chinese domain names with suffixes such as .手机 (.mobile). In 1998, the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) started the technical development of Chinese domain names, marking the integration of Chinese characters into the international Internet domain name system. In 2009, .中国 (.China) was successfully approved by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), becoming a global generic top-level domain. Since 2013, Chinese top-level domain names such as .我爱你 (.iloveyou), .手机 (.mobile), .集团 (.group), .网络 (.network), .信息" (.information), .网址 (.website), .在线 (.online), .公司 (company), .游戏(.game)and many others have successively appeared on the Internet stage. Here are some examples of domain names using Chinese characters: 中国科学院.网址,华为.网址,南博会.网址,中国国际信息通信展览会.网址, 成都大运会.网址,中央电视台.中国,QQ.中国, 腾讯.中国, 中国移动.中国.

Top-level domains are represented by both simplified and traditional characters (中國), specific punctuation marks can be used.[12] Moreover, the use of Latin letters restrict the recognition of the brand in China. Researcher Li Jingyi acknowledges the inconvenience of language use on the Internet for non-English speaking countries, citing the example of two companies whose domain names could be confused. They are 内蒙伊利集团股份有限公司(www.yili.net) and 伊丽服饰有限公司 www.yili.com (Li, 2010). Thus, Chinese-character domain names can use entirely Chinese names for company websites, adapting to the language habits of Chinese people, meeting the needs to promote brands and quickly access information, and helping businesses better participate in Internet competition.

Conclusion

Since the birth of the Internet English has been the dominant language. However, the increasing involvement of users from different countries and nations is transforming this space. Localization of websites, games and adaptation to different phenomena are clear indicators of this evolution. Some researchers believe that multilingualism is a necessary and natural phenomenon for the Internet’s evolution, emphasizing the importance of accommodating various languages. Meanwhile, Chinese experts argue that relying solely on the English language hinders the development of the Internet. That is to say, with each passing year, the Internet space continues to expand and become an integral part of virtual reality, increasingly shaping the linguistic expression of the online environment. Thus, the comprehensive exploration of current trends in naming numeric and ideographic domains, taking into account linguistic and cultural factors, is of outmost importance. The other reason is that domain names act as door numbers on the Internet.

Numeric and Chinese-character nomination serves as a part of the virtual linguistic worldview of users. The conclusion drawn is that domain names play a crucial role in shaping the virtual linguistic landscape of the Internet and are intricately linked to the cultural and linguistic preferences of users. For instance, homophonic coding demonstrates that the sound aspect of the form of a virtual name is of fundamental importance. Companies may use numeric domain names as part of their branding strategy, especially if the numbers have significance to the business. Creative language use, as demonstrated by linguistic material, showcases the inventive utilization of language in the digital realm. Moreover, the popularization of Chinese domain names is beneficial to the promotion of Chinese culture on the Internet, contributing to the construction of a culturally strong and network-strong country. Thus, analyzing ideographic domains contributes to refining our understanding of the role of language in maintaining sovereignty.

[1] Internationalized Domain Name World Report. URL: https://www.idnworldreport.eu/ (Accessed 23 December 2023).

[2] Давыдова Н.Н. Виртуальные онимы в итальянской интернет-среде. Выпускная квалификационная работа. Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, 2017. URL: https://dspace.spbu.ru/bitstream/11701/8345/1/Davydova_VKR.pdf (Accessed 15 June 2023).

[3] Тенденции развития интернета: готовность экономики и общества к функционированию в цифровой среде: аналитический доклад / Г. И. Абдрахманова, М. Д. Ванюшина, К. О. Вишневский, Л. М. Гохберг и др.; АНО «Координационный центр национального домена сети Интернет»; Нац. исслед. ун-т «Высшая школа экономики». М.: НИУ ВШЭ, 2021. 248 с.

[4] Поддерживаю.РФ URL: https://xn--80adfafgo7bio2n.xn--p1ai/ (Accessed 23 August 2023).

[5] Internationalized Domain Names. URL: https://en.unesco.org/internationalized-domain-names (Accessed 08 September 2023).

[6] 《“十四五” 信息通信行业发展规划》解读 URL: https://www.miit.gov.cn/zwgk/zcjd/art/2021/art_8f8e9251b74940979e1f422203eeb6af.html (Accessed 24 December 2023).

[7] Домен .AI вырос более чем на 50 тысяч регистраций за три месяца. URL: https://cctld.ru/media/news/industry/35408/ (Accessed 26 December 2023).

[8] Nine Millions of Domain Names Are “Just Numbers” URL: https://domains-index.com/nine-millions-domain-names-just-numbers/# (Accessed 05 February 2023)

[9] 阿飞:对纯数字域名的一点看法 URL: https://www.xinnet.com (Accessed 15 November 2023)

[10] 六间房 URL: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/cedbddd4ef3a87c24028915f804d2b160a4e8679.html?_wkts_=1704179893909&bdQuery=%E5%85%AD%E9%97%B4%E6%88%BF%E4%B8%BA%E4%BB%80%E4%B9%88+%E7%94%A8%E5%85%AD&needWelcomeRecommand=1 (Accessed 28 December 2023)

[11]四数字域名只知道“1688”,还有这些网站,你都用过吗?URL: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1675871967586057745&wfr=spider&for=pc (Accessed 23 August 2023)

[12] 工业和信息化部关于调整中国互联网域名体系的公告 URL: https://www.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/xgj/wjfb/art/2020/art_7b446feb028b4607a158b12530cd2b3e.html (Accessed 12 December 2023)

Список литературы

Abdullaeva M. Z. Spiritual role of Islamic media space in domain “uz” / M. Z. Abdullaeva // Bulletin Social-Economic and Humanitarian Research. 2020. №. 8 (10). Pp. 55–62. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4117558

Akhrenova N. A. The role of numbers in the Chinese cyberculture / N. A. Akhrenova, M. N. Dubinina // Topical Issues of Linguistics and Teaching Methods in Business and Professional Communication – TILTM 2022: Proceedings of the X International Research Conference Topical Issues of Linguistics and Teaching Methods in Business and Professional Communication, TILTM 2022, Moscow, 22–23 апреля 2022 года. – Moscow: ISO LONDON LIMITED European Publisher, 2022. Pp. 16–23. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22104.3

An Zh. Wǎngluò shùzì xiéyīn cíyǔ qiǎn lùn [A brief discussion on homophonic words for digital numbers on the Internet]/ Zh. An // Journal of Taiyuan University. 2002. № 3 (4). Pp. 36 –38.

Arsène S. Shaping the Chinese Internet Special Feature Internet Domain Names in China Articulating Local Control with Global Connectivity / S. Arsène// China Perspectives. 2015. № (4). Pp. 25–34. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.6846

Баринова Д. С. Национальные домены интернета – символы государственных границ и безграничных возможностей / Д. С. Баринова // Вестник МГИМО Университета. 2010. № 5 (14). С. 307–314.

Чайкисова А. В. Специфика идеонимов как особого типа имен собственных / А. В. Чайкисова // Актуальные проблемы германистики, романистики и русистики. 2017. № 3. С. 23–24.

Кутюр С. Что означает понятие «суверенитет» в цифровом мире? / С. Кутюр, С. Тоупин // Вестник международных организаций: образование, наука, новая экономика. 2020. Т. 15. № 4. С. 48–69. https://doi.org/10.17323/1996-7845-2020-04-03

Дальдинова Э. О. Г. Характеристика немецкоязычных сайтонимов / Э. О. Г. Дальдинова, Д. В. Бардаева // Интеграционные процессы в современной науке: сборник научных трудов по материалам XIX Международной научно-практической конференции, Анапа, 26 апреля 2021 года. – Анапа: Общество с ограниченной ответственностью «Научно-исследовательский центр экономических и социальных процессов» в Южном Федеральном округе, 2021. С. 10–13.

Дальдинова Э. О. Г. Структурная характеристика немецкоязычных сайтонимов / Э. О. Г. Дальдинова, Т. В. Бураева // Вестник Иссык-Кульского университета. 2023. № 54-2. – С. 65–73.

Дедова О. В. Заголовочный комплекс в электронной коммуникации / О. В. Дедова, М. С. Куприенко // Вестник Московского университета. Серия 9: Филология. 2013. № 1. С. 61–70.

Дубинина М. Н. Цифровые коды интернет-коммуникации (на примере английского, русского и китайского языков) / М. Н. Дубинина // Актуальные проблемы германо-романской филологии и методики преподавания иностранных языков: Сборник научных статей, Коломна, 09 февраля 2022 года. М.: Некоммерческое партнерство «Национальное общество прикладной лингвистики», 2022. С. 23–26.

Духанина Л. Н. Анализ сетевого онко-дискурса трехлетней ретроспективы в домене верхнего уровня RU / Л. Н. Духанина, А. А. Максименко // Вопросы онкологии. 2020. Т. 66. № 4. С. 315–324. https://doi.org/10.37469/0507-3758-2020-66-4-315-324

Филимоненко Е. Н. Культурные и лингвистические аспекты немецкоязычных сайтонимов / Е. Н. Филимоненко // Научно-исследовательский центр "Вектор развития". 2023. № 19. С. 185–190.

Fu Y. Yīnghàn shùzì xiéyīn cí yìtóng de shēncéng jiěxī [An in-depth analysis of the similarities and differences between English and Chinese numerical homophonic words]/Y. Fu// Language Application Research. 2013. №. 9. Pp. 135–137.

Габдрахманова Г. Ф. Национальный интернет России: к постановке проблемы / Г. Ф. Габдрахманова, З. А. Махмутов // Oriental Studies. 2018. Т. 11. № 3 (37). С. 142–151. https://doi.org/10.22162/2619-0990-2018-37-3-142-151

Хань Ю. Культурное осмысление омонимии числительных в современном китайском языке / Ю. Хань // Современные востоковедческие исследования. 2022. Т. 4. № 2. С. 30–39. https://doi.org/10.24412/2686-9675-2-2022-30-39

Игнатов А. А. Управление Интернетом в повестке БРИКС / А. А. Игнатов // Вестник международных организаций: образование, наука, новая экономика. 2022. Т. 17, № 2. С. 86–109. https://doi.org/10.17323/1996-7845-2022-02-04

Калятин В. О. Доменные имена / В. О. Калятин. М.: Информационно-издательский центр Роспатента «ИНИЦ», 2002. 188 с.

Карпенко М. Ю. Выделение базовой единицы Интернет-ономастикона / М. Ю. Карпенко // Мова. 2012. № 17. С. 113–115.

Карпенко М. Ю. Мотивация сайтонимов англоязычного сектора Интернета / М. Ю. Карпенко // Вестник Воронежского государственного университета. Серия: Лингвистика и межкультурная коммуникация. 2014. № 2. С. 35–39.

Ke X. Zhōngwén yùmíng de qiánshì jīnshēng [The past and present life of Chinese domain names]/ X. Ke// Zhongguancun Theory. 2020. № 12. Pp. 66–68.

Kersten S., Lotze N. Anonymity and authenticity on the web: Towards a new framework in internet onomastics/ S. Kersten, N. Lotze // Internet Pragmatics. 2022. № 5 (1). Pp. 38–65. https://doi.org/10.1075/ip.00074.ker

Хазова, А. Б. Изучение компьютерно-опосредованной коммуникации в лингвистическом аспекте / А. Б. Хазова // Вопросы языкознания. 2023. № 2. С. 144–156. – https://doi.org/10.31857/0373-658X.2023.2.144-156

Куприенко М. С. Лингвостилистический анализ приемов создания доменных имен Рунета / М. С. Куприенко // Гипертекст как объект лингвистического исследования : Материалы Всероссийской научно-практической конференции с международным участием, Самара, 15–16 марта 2010 года / Ответственный редактор: С. А. Стройков. – Самара: Самарский государственный социально-педагогический университет, 2010. С. 80–83.

Кузнецов А. В. Языковая игра в названиях доменов / А. В. Кузнецов // Наука и бизнес: пути развития. 2012. № 4 (10). С. 42-44.

Li J. Zhōngwén yùmíng yǔ jìng xià de yùmíng zhùcè wèntí xīn jiě [New solutions to domain name registration issues in the context of Chinese domain names] / J. Li// Journal of Hunan Public Security College. 2010. № 22 (4). Pp. 117–121.

Мадиева Г. Б. Общие проблемы ономастики / Г. Б. Мадиева, В. И. Супрун // Теория и практика ономастических и дериватологических исследований: Коллективная монография Памяти заслуженного деятеля науки Республики Адыгея и Кубани, профессора Розы Юсуфовны Намитоковой / Научные редакторы В. И. Супрун, С. В. Ильясова. Майкоп: Издательство «Магарин Олег Григорьевич», 2017. С. 11–51.

Поляк Ю. Е. Интернационализированные кириллические домены верхнего уровня / Ю. Е. Поляк // Современные проблемы и перспективные направления инновационного развития науки: сборник статей по итогам Международной научно-практической конференции, Новосибирск, 12 марта 2018 года. Том 2. Часть 2. Новосибирск: Общество с ограниченной ответственностью «Агентство международных исследований», 2018. С. 116–119.

Рожкова М. Доменные имена как идентификаторы и средства коммуникации / М. Рожкова // Хозяйство и право. 2015. № 3(458). С. 55–70.

Рябченко Н. А. Топонимика сетевого ландшафта online-пространства / Н. А. Рябченко // Человек. Сообщество. Управление. 2016. Т. 17. № 4. С. 98–115.

Ширин С. С. Российские инициативы по вопросам управления Интернетом / С. С. Ширин // Вестник МГИМО Университета. 2014. № 6 (39). С. 73–81.

Сон Л. П. Виртуальная ономастика и невербальный компонент Интернет-коммуникации / Л. П. Сон // Научный вестник Воронежского государственного архитектурно-строительного университета. Серия: Современные лингвистические и методико-дидактические исследования. 2012. № 18. С. 123–134.

Сон Л. П. Виртуальная интеракция: "Что в имени твоем..." / Л. П. Сон // Ученые записки Российского государственного социального университета. 2009. № 6 (69). С. 217–221.

Супрун В. И. Развитие ономастического пространства Интернета / В. И. Супрун // Ономастика Поволжья: материалы IX Международной конференции по ономастике Поволжья, Волгоград, 09–12 сентября 2002 года. Волгоград: Институт этнологии и антропологии им. Н.Н. Миклухо-Маклая РАН, 2004. С. 53–59.

Xiang X. (2012, December). Linguistic and Cultural Characteristics of Domain Names of the Top Fifty Most-Visited Websites in the US and China: A Cross-Linguistic Study of Domain Names and e-Branding/ X. Xiang// Names. № 60 (4). Pp. 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1179/0027773812Z.00000000032

Закалкин П. В. Эволюция Систем Управления Киберпространством / П. В. Закалкин // Вопросы кибербезопасности. 2022. № 1 (47). С. 76–86. https://doi.org/10.21681/2311-3456-2012-1-76-86

Жильцов Д. А. Особенности доменного нейминга в стратегии интернет-маркетинга организации / Д. А. Жильцов // Маркетинг и логистика. 2020. № 3 (29). С. 33–40.

Зубарева А. В. Новые тенденции в системе неличных собственных имен в русском языке / А. В. Зубарева // Лингвориторическая парадигма: теоретические и прикладные аспекты. 2021. № 26-2. С. 100–102.

Зубарева А. В. Онимы в интернет-коммуникации: новые явления и функции / А. В. Зубарева // Актуальные проблемы филологии и педагогической лингвистики. 2021. № 1. С. 120–136. https://doi.org/10.29025/2079-6021-2021-1-120-136

Zhou Y. Shùzì xiéyīn de yǎnbiàn [The evolution of number homophony] / Y. Zhou // Rhetoric Learning. 2003. № 1. Pp. 35–37.

Zhu G. Wèishéme zhōngguó hùliánwǎng dìzhǐ piānhào shùzì yùmíng [Why do Chinese Internet addresses prefer digital domain names?] / G. Zhu // Computers and Networks. 2014. № 1. Pp. 43–44.