CONCEPTUAL METAPHORS OF ANGER IN CHINESE AND ENGLISH: A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS

Aннотация

К сожалению, текст статьи доступен только на Английском

Introduction. The importance of metaphor is difficult to overestimate. Historically, the metaphor was considered to be a set of figurative linguistic expressions which are decorative and ornamental in their nature and served only as a figure of speech and its study was mostly the prerogative of literature and rhetoric [Lakoff 1986]. Though the situation changed in the past few decades and the interest to the cognitive nature of metaphor has grown rapidly; according to Lakoff and Jonson’s seminal book “Metaphors We live By”, metaphor in its broad sense, is crucial in a language and thought. During the last two and a half decades, this theory has been developed in works by Akhundov [1986], Alverson [1994], Dirven [1993], Goddard [1996], Kövesces [2006], Steen et al [2003], to mention just a few.

The contemporary theory of metaphor claims that more abstract concepts can be understood and expressed metaphorically in spatial terms. The central claim of this theory is that emotions, which are highly abstract in their nature, are conceptualized and expressed in the form of metaphors. For instance, the emotion of anger in English is conceptualized in terms of heat and internal pressure [Lakoff and Jonson 1980], it gives us the question up to what extent it is also true for the Chinese language. Taking into consideration the theory that a metaphor can be explained as the mapping between source and target domains, this paper examines similarities and differences of mappings across domains in Chinese and English.

Metaphors of Anger in English

The metaphors of emotions are crucial for understating the human cognition, according to Ortony: “Emotion is one of the most central and pervasive aspects of human experience” [Ortony et al. 1988, p.3] and the most direct for analysis access to emotions we have is through a language [Ortony et al. 1988].

Following the principles of cognitive semantics, a language can be a tool for discovering the contents of emotion concepts [Kövesces 1990]. It’s considered that metaphors play and important role in the scientific conceptualization of emotions.

The number of researches has been conducted on the function of metaphor in the conceptualization of “anger” in English [Fesmire 1994, Lakoff and Jonson 1980 et al.], the central idea in these studies is that a metaphor serves as a source for the conceptualization of emotions and is grounded in bodily experience. This claim is supposed to be universal but the evidence supporting the idea are mainly derived from English.

According to Lakoff and Kövesces [1987], “The cultural model of psychological effects, especially the part that emphasizes HEAT, forms the basis of the most general metaphor for anger: ANGER IS HEAT.” This metaphor is subdivided into two constituent parts: solids and fluids. When this metaphor is applied to solids, the metaphor acquires the version Anger IS FIRE. This concept can be found in numerous metaphors, for instance:

- He was breathing fire.

- Smoke was pouring out of his ears.

- She burnt with indignation.

- Your behavior just added fuel to the fire!

- Those are inflammatory remarks.

These expressions represent two different images of a container. The first one suggests that a body of a person who is angry is a container and it is filled with a fire burning inside. The second one, on the contrary, implies that there is the fire burning outside the body which makes the container hot. The second image is closely related to the second version of the ANGER IS HEAT in English metaphor, and is applied to fluids acquiring the version ANGER IS A HOT FLUID IN A CONTAINER. This version can be illustrated with the following examples:

- Simmer down!

- You make my blood boil.

- I have reached the boiling point.

- He blew his top.

- She was seething with rage.

These examples illustrate the destructive power of anger compared to hot fluid which produces too much stem in a closed container, thus the steam has to find its way out; otherwise the explosion is irrevocable.

The English language, governed by the common cultural model, makes use of a general metonymic principle: the part stands for the whole or in our case: EFFECTS OF AN EMOTION STAND FOR THE EMOTION. Thus we can observe a system of metonymies for anger [Yu,1998]:

BODY HEAT

- Don’t get hot under the collar.

- When the cop gave her a ticket, she got all hot and bothered and started cursing.

INTERNAL PRESSURE

- He almost had a hemorrhage.

- When I found out, I almost burst a blood vessel.

REDNESS IN FACE AND NECK AREA

- She was scarlet with rage.

- He got red with anger.

AGITATION

- He was quivering with rage.

- He was hopping mad.

PHYSICAL MISPERCEPTION

- I was so mad I couldn’t see straight.

- She was blind with rage.

Metaphors of Anger in Chinese

According to Kövesces, “Languages are not monolithic but come in varieties that reflect divergences in human experience” [2006, p.161]. Though the conceptual metaphors may have the same source domain within different cultures. In the Chinese language, ANGER IS HEAT is applied to solids and the source domain ANGER IS FIRE coincides with the English language. For instance:

- Pinyin: Bie re wo fa-huo

Simplified Chinese: 别惹我发火。

English translation: Don’t set me on fire (i.e. Don’t cause me lose my temper).

- Pinyin: Ta zheng-zai hou tou shang.

Simlified Chinese: 他正在火头上。

English translation: He is at the height of fire (i.e. on the top of his anger).

In the Chinese language visceral organs can serve as a source domain for “INTERNAL HEAT” creating container metaphors, for instance:

- Pinyin: Ta-de gan-huo hen wang.

Simplified Chinese: 他的肝火很 汪。

English translation: His liver-fire is roaring (i.e. He is hot-tempered).

- Ta xin-tou huo qi.

Simplified Chinese: 她心头火起。

English translation: Her heart-head fire flare up (i.e. She flared up with anger).

- Pinyin: Ta wo le yi duzi huo.

Simplified Chinese: 她握了一肚子火。

English translation: She held in a belly of fire (i.e. She was simmering with rage).

The examples illustrate that both English and Chinese share the common conceptual metaphor ANGER IS FIRE. Both languages express the essence of this emotion as a dangerous one. The main difference between English and Chinese is that the Chinese language tends to use body- related words such as internal organs. These words intensify the idea that anger can cause many medical problems, effecting particular parts of the body. The conceptualization of anger by means of using body-related words supports the theory that metaphors of emotions are grounded on bodily and physiological experience and that this can be regarded as a cross-linguistic phenomenon.

The second version of metaphor ANGER IS HEAT is represented in the Chinese language as ANGER IS THE HOT GAS IN THE CONTAINER, which differs from the English version ANGER IS HOT FLUID IN THE CONTAINER. This metaphor is based on the common knowledge of physics, when a gas is heated in a container, it expands and causes the increase of internal pressure. For instance:

- Pinyin: Ta pi-qi hen da.

Simplified Chinese: 她脾气很大。

English translation: She’s got big gas in spleen (i.e. She is short-tempered).

- Pinyin: Wo xin-qi bu shun.

Simplified Chinese: 我心气不顺。

English translation: I heart-gas not smooth (i.e. I am feeling unhappy).

- Pinyin: Ta qi-gugu de.

Simplified Chinese: 他气鼓鼓的。

English translation: He gas-inflate (i.e. He is inflated with anger).

- Pinyin: Ta nu-qi chongchong.

Simplified Chinese: 他怒气冲冲。

English translation: He angry-gas soar-soar (i.e. He is in a great rage).

- Pinyin: Ta qi-shi xiongxiong.

Simplified Chinese: 她气势熊熊。

English translation: She gas-force surge-surge (i.e. She is full of anger).

As can be seen English and Chinese have different source domains: FLUID and GAS, but they share basic metaphorical entailments. These source domains share similar ideas of HEAT, INTERNAL PRESSURE, and DANGER OF EXPLOSION, which allow them to reach the target domain ANGER.

In the previous section, we have illustrated that the English language follows the metonymic principle: THE PSYCHOLIGICAL EFFECTS OF AN EMOTION STAND FOR THE EMOTION. The Chinese language follows the same principle, for instance:

BODY HEAT

- Pinyin: Wo qi de lian-shang huo-lala de.

Simplified Chinese: 我气的脸上火辣辣的。

English translation: I gas face-on fire-hot (i.e. I got so angry that my face was peppery hot).

INTERNAL PRESSURE

- Pinyin: Bie qi po le du-pi.

Simplified Chinese: 别气破了肚皮。

English translation: Don’t break your belly skin with gas (RAGE).

REDNESS IN FACE AND NECK AREA

- Pinyin: Tamen zheng de gege mian-hong-er-chi.

Simplified Chinese: 他们争的个个面红耳赤。

English translation: They argues until everyone became red in the face and ears.

It is interesting to observe that in the given expression, the red color is rendered into Chinese with two different characters: 红/赤. The character 赤 is more bookish, while 红 is widely used a spoken language, but in our example different characters meaning RED are used to avoid repetition.

AGITATION

- Pinyin: Ta qi de hun-shen fadou.

Simplified Chinese: 她气的浑身发抖。

English translation: Her body was shaking all over with rage.

PHYSICAL MISPERCEPTION

- Pinyin: Wo qi de liang yan fa hei.

Simplified Chinese: 我气的两眼发黑。

English translation: I was so angry that my eyes turned blind.

Having compared the examples in English and Chinese, we can come to the conclusion that the metonymic expressions are similar in two languages. It can be explained with the fact that these metaphors are primarily based on physiological effects of anger which tend to be universal. The difference between English and Chinese is the use of body parts, the Chinese language specifies more body parts than English does.

English and Chinese share the same conceptual metaphor ANGER IS HEAT, but English operates the notions of FIRE and FLUIDS while Chinese selects FIRE and GAS. Both languages follow the same metonymic principle in emotion of anger description by referring to different physiological effects.

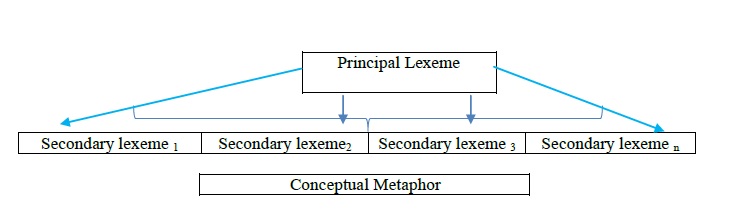

The principal difference between conceptual metaphors in English and Chinese is in the mapping between source and target domains. The English language conceptualize the emotion of ANGER by means of two source domains FIRE and FLUID and the word FIRE acquires the metaphorical meaning (let’s call it a direct conceptualization). Thus we can say that the direct lexical meaning can be transferred into metaphorical. On the other hand, the lexeme FLUID does not possess the direct metaphorical reference to the conceptual metaphor of ANGER but it requires other “secondary” lexemes that are associated with FLUID to create a metaphor (indirect conceptualization). We can see it as a continuum:

The principal difference between conceptual metaphors in English and Chinese is in the mapping between source and target domains. The English language conceptualize the emotion of ANGER by means of two source domains FIRE and FLUID and the word FIRE acquires the metaphorical meaning (let’s call it a direct conceptualization). Thus we can say that the direct lexical meaning can be transferred into metaphorical. On the other hand, the lexeme FLUID does not possess the direct metaphorical reference to the conceptual metaphor of ANGER but it requires other “secondary” lexemes that are associated with FLUID to create a metaphor (indirect conceptualization). We can see it as a continuum:

Figure 1. Indirect lexical conceptualization of the metaphor

As can be seen from the illustrative material, the lexeme FLUID does not acquire the direct metaphorical meaning ANGER but this metaphorical meaning is realized by secondary lexemes such as: boiling, simmer, stew etc.

It should be noted that the Chinese words fen 愤 and nu 怒 are literal lexemes for the emotion of anger but they are different from huo 火(fire) and qi 气(gas) in their meaning and style. In most cases these direct words cannot substitute huo 火(fire) and qi 气(gas). It makes these words (fire and gas) so conventionalized metaphors of anger that native speakers of Chinese accept them literary not metaphorically. The derivatives of these lexemes also acquire metaphorical meaning. For instance:

- Fa-huo 发火 -denotate

- Dong-huo 动火 - flare up

- Shang-huo 上火- get angry

- Sheng-qi 生气- get angry

- Dong-qi 动气 - get angry

As can be seen, some meanings have already lost their metaphorical meaning and are perceived literary.

Conclusion. The metaphors of anger in English and Chinese shareboth similarities and differences. They share the same universal concept ANGER IS HEAT, which is an embodied metaphor based on human physiological perception regardless of language and culture. On the other hand, we can observe some differences that can be explained by different cultural beliefs. The source domains in English and Chinese differ but the mapping between the source and target domain remains the same.

Список литературы

Список использованной литературы появится позже.