Genre as an ontologically unstable literary and artistic form

Abstract

The article is devoted to the problem of the genre. The article examines the text of a modern French novel, which has undergone radical changes in recent decades. The French novella is so new that researchers define it in terms of hybridization, crossing, transition, transgression, hybrid text, quasi-novella. Therefore, the question seems to be justified: does a new genre generate or does a genre change, while retaining its main typological characteristics? The results of the analysis confirm the opinion of M.M. Bakhtin that the dialogization of secondary genres is currently changing. The French short story is rebuilt and updated: the text as a whole takes on a different form, its balanced, extremely clear and logically verified structure split into indirectly related parts, which are photographs, diagrams, drawings and various fonts that form more or less related thematically blocks. The perfect grammatical forms inherent in the classical novelistic form have given way to present ones, the monologue component is replaced by the dialogical one, which entails a change in the category of the reader. The text introduces him as an active agent into the event and invites him to join the game. The compositional structure gives the text an interactive, playful character, responding to the time request for communication in a playful format, which enhances the “partner” character of the category of the reader, who acquired the properties of a co-author / co-narrator and qualitatively changed the narration, turning it into communication, which raises the problem of defining a new kind of narrative technology. The genre under study today retains its typological characteristics, such as brevity and a story about one event, which makes it possible to consider it as a novel, but it loses such an essential property for its typification as coup de théâtre, an unexpected denouement, which is considered by all theorists of the genre as its cornerstone. To solve these problems, it is necessary to wait for studies that would show the possibility of considering these changes as a free creative re-design of the novelistic genre or as recognition of the birth of a new artistic and literary genre.

Introduction

Researchers of the French narrative note changes in such secondary (according to Bakhtin) genres as the novel and the novella, which take place as early as in the first half of the twentieth century and continue to occur in the present century. It has been noted more than once that the modern text does not stop looking for its new forms of expression, that a distinctive feature of world literature in general, and French, in particular, can be defined as a continuous change in the compositional form of the text and the manner of presentation of its content. It seems that the authors are cramped (or bored) within the framework of one long-existing genre, and they strive not so much to go beyond it, as to blend it with others to a greater or lesser extent, to change it in one way or another, to bring something that is typical of another genre, another type of text. This characteristic of the modern French text is realized as soon as the reader opens the book. Therefore, the question seems to be justified: does a new style of literary writing generate new genres, or does the genre change while maintaining its main typological characteristics? And if it changes, what is preserved in it that makes it possible to consider a new text as belonging to an already existing literary genre or a new genre is being born? Whether the rights of M. M. Bakhtin, arguing that "the genre was given to man as a language, without it, would not be able to communicate"?

This article attempts to answer these questions on the basis of analysis and interpretation of texts of French literature of the second half of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, mostly of short texts of the genre (novel, short story), because at the present time, this genre has been a great development in French literature. Novels are published in great numbers by a large number of writers-novelists, among them a lot of novelists-women: A Somon, C. Baros, M. Duras, M. Burducks, M. Yoursenar others, which in itself seems an event of special significance and causes research interest. In the women's novelistic text, according to K. Potvin, the problems of genre and gender most visibly intersect. The women's novelistic text combines "socio-political and cultural construction in the postmodern sense, and the feminist utopia itself has become a "genre" that serves to destabilize genres" (Potvin, 2001:76).

Modern French novelistic prose has such a new character that researchers introduce the terms hybridization, crossing, intermediate link, transition, transgression, hybrid text, which is characterized primarily by a different compositional structure, namely, a "split" form (structure éclatée). At the same time, hybrid texts, according to J.M. Paterson (2001: 91), are more endowed with meaning than others and are already embedded, despite their novelty, in our cognitive and epistemological systems. Proceeding from the above, it seems interesting to analyze the modern French novelistic text in the aspect of its genre features, having previously said a few words about the genre as such.

About the novella genre

As is known, the first who turned to the genre was Aristotle, who proposed in his "Poetics" (Aristotle, 1998: 1064-1067) the division according to the root principle – into diegesis and mimesis. The great scientist highlighted the main thing, pointing out the significance of the presence/absence of a speaking voice in the characterization of any text, the need to determine the type of text depending on whether there is one voice telling a story in it, or many talking voices that are not telling a story, but expressing their opinions, exchanging impressions and/or discussing.

The diegesis type underlies the narrative, narrative text, the mimesis type is dramatic, imitating natural communication, which today can be defined as a discursive genre or speech in the literal sense of the word.

Identifying the distinctive features of epic, tragedy, comedy, dithyrambic poetry and other genres, Aristotle pointed out that the basis of the differences between them is "the way each phenomenon is reproduced." He drew attention to the fact that it is possible to tell about the same thing in different ways and that the form of utterance depends on how the story is conducted: "After all, you can reproduce [...] by telling about events, while becoming something extraneous (to the story) [...], or on your own behalf, without replacing yourself with others; or depicting everyone acting ..." (Aristotle, 1998:1069).

The scientist also emphasized the importance in determining the genre of such a category as a personal pronoun in the function of the narrator, its form, as well as the fact of its presence or absence, as in a dramatic text.

Since those distant times, the genre has not ceased to interest scientists, although in different periods of the development of philological science, this interest has been increasing, then temporarily lost its relevance. Nowadays, there are two reasons why the genre is increasingly moving into the spotlight: firstly, as noted above, the endless attempts of writers to change/ reshape/update the genre as such, to introduce elements into each individual genre structure that it has never possessed before.

So, according to F. Goyet, since the thirties of the 20th century the French novella has been experiencing, a transformation of such force that it turns into a quasi-novella genre. The researcher suggests defining it as a "modernist novel" because it is strongly influenced by modernism: "C'est le moment où le genre, subit une transformation radicale, transformation tellement profonde que l'on sait à peine si l'on peut continuer à employer le même mot pour désigner les textes de la nouvelle qui apparaît à ce moment [...] un genre quasi -nouveau, la nouvelle "moderne", puisqu'on verra qu'elle est liée en profondeur aux conquêtes du modernisme" (Goyet, 2001: 87).

Reflecting on the reasons for the transformation, M. Macé characterizes the diverse attempts of writers to change the genre with the argot word encanailler, which means "to bully". She assures that all these modifications ("tormenting" by Masa) of the genre are in vain, that no matter how numerous they are, the genre will not go anywhere and will definitely return": «On aura beau encanailler la littérature et les arts contemporains, … le genre reviendra sans doute toujours…» (Macé, 2001: 5).

Thus, numerous modifications of the genre generate, firstly, a natural research interest, make scientists realize and identify these changes and understand the degree of their influence on the novelistic genre and its consequences.

Secondly, according to the general opinion, "a kind of impetus to the study of genre studies was the republication of M.M. Bakhtin's scientific works" (Bakhtin, 1996: 3), in which the scientist emphasizes the importance of compositional construction as one of the most important factors in the formation of the speech genre along with thematic content and style. In the "Problem of Speech Genres" M.M. Bakhtin writes that it is this trinity – composition, content and style – that, being "inextricably linked in the whole of utterance", determines the specifics of the speech genre in each separate sphere of communication (Bakhtin, 1996: 159-206).

At the same time, the paper points to the extreme heterogeneity of verbal and written genres, which allows, in the author's opinion, to assume the impossibility, due to their abstractness, of distinguishing their common features.

M.M. Bakhtin also sees in this very diversity the reason that "the general problem of speech genres has never really been posed," although literary, rhetorical, everyday speech genres have been studied since antiquity, but without taking into account the general linguistic problem of utterance and its types.

A similar state of affairs is characteristic, according to the scientist, for most research works: for the works of F. de Saussure and his students, for structuralists and American behaviorists, who also failed to determine its general linguistic nature.

In our opinion, the relevance of research interest in the genre lies in this "indecision" from the perspective of taking into account the general linguistic problem of utterance.

In the proposed work, an attempt is made to identify the boundaries (according to M.M. Bakhtin) of the genre of the French novella, separating it from other artistic and literary genres and allowing to define the modified text as a novella, as well as to identify the modifications to which the French novella has been subjected in recent decades.

In this regard, it is necessary to say a few words about the classic French novel.

Canonical (classical) French novella

It is known that, from the point of view of visual image and compositional structure, the canonical short story text, like the text of a novel and any narrative, represents a solid white space filled with black lexical units and syntactic structures, which can be interrupted by a gap, usually small, indicating a pause in the story or a transition to a new topic. Visually, the text has the appearance of an ordinary, traditional artistic publication, whether it is a novel, a story, a fairy tale or a novella.

The traditional novelistic theme is also known. For example, O. Balzac's short stories, being an integral part of his Human Comedy, aimed to tell about the life of an entire country in its smallest manifestations. The theme of Guy de Maupassant's novels was the drama of the existence of simple little people. Flaubert, Zola, Sand, Stendhal were attracted by man and society, the difficulties of existence, high passions, petty meanness’s and various kinds of psychological dramas.

One of the characteristic stylistic features of the classic novel is its monologue. The narrator, regardless of his form ("I" or "he"), narrates without taking into account the presence/absence of the reader, who plays rather a passive role of a listener listening to the narrating voice. The narrator, although speaking for him, does not address him, there is, for example, no direct appeal to the reader, as is typical for a novel by, say, O. Balzac, who likes to "talk" with his reader and address him with a speech.

There are also no other markers of dialogicity, which is most clearly indicated by the perfect verb-pronominal forms used – Passé simple, the third-person pronoun in the function of the narrator and the adverbs "there" and "then", producing a classical narrative, which, although it can be considered as a form of the author's utterance, but which assumes the reader only as a listener, emotional, sympathetic, but not taking part in the process.

This trinity of grammatical forms reflects the linguistic essence of the French novella, its peculiarity and the meaning of existence – the novella is told so that an unexpected final act, an amazing denouement takes place, all these grammatical means "work" for this. With their help, a novelistic narrative is produced, which has a pronounced monological character, as a result of which the reader does not act as a partner-interlocutor of the author, although the narrator seeks to surprise or amaze him.

E.M. Evnina, noting the absence of interference in the French novella "with his author's word," writes that no one imposes his attitude to the depicted on the reader, while referring to Flaubert's position: "the author should be like God in his creation, omnipotent, but invisible" (Evnina, 1976:11). As evidenced by the opinion of a venerable French writer, at that time there was no attitude to communication itself, and short story writers had no purpose to engage in conversation with their readers.

Updating the speech genre of the novel

The analysis of the texts of the novellas of the modern era shows that these grammatical forms have changed, followed by a significant modification of their main categories, defining the specifics of this speech genre.

As it was noted, the French novel has been undergoing numerous radical changes, which are expressed in the "game" of the authors on its volume, visual image, page space and even on the subject. Under the influence of these modifications, the novel acquires a new property – dialogicity, which consists in a special manner of conducting a dialogue with the reader, which is based primarily on a specific composition and a peculiar novelistic structure.

The results of the analysis of French modern short stories confirm M.M. Bakhtin's opinion that the dialogization of secondary genres is currently changing. The French novel is being rebuilt and updated: the text as a whole takes on a different form, perfect grammatical forms have given way to presentable ones, the monological component is replaced by a dialogic one, which entails a change in the category of the reader.

New structure of the novel

The compositional form of the modern novel is extremely diverse, which radically distinguishes it from the classic novel. The structure of the latter is a relatively short story about an unusual and surprising event, the tension of which is resolved in an unexpected denouement, the so-called coup de théâtre – an unexpected final act.

Its balanced, extremely clear and logically verified structure has split today into indirectly related parts, which are photographs, diagrams, drawings and various fonts, forming more or less thematically related blocks.

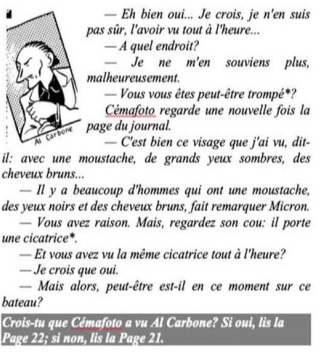

Thus, D. Renaud in Enquête sur un bateau-mouche organizes the text as follows:

As can be seen from the fragment of the text, the author introduces several elements that are not characteristic of canonical narration. They include: a drawing in the upper left corner, bold italics, standard italics and the opposition of black and white colors.

It must be recognized that it is not entirely correct to define the style of the presentation of this text as a narrative, since it is not a "story about ...", but a dialogue between the characters, which is interrupted by the appeal of the narrator (author?) to the "real" reader to ask him if he believes what is being told and refer him to page 22 if so, and to page 21 if not. As a result, instead of narrative, there are two dialogues in the text, one of which is a conversation between the characters, the second is a dialogue with the reader, built by the author based on visual means and direct questions addressed to the reader by the author. The form and questions require the reader to "intervene" in the text in the form of an "answer" to the author's questions. Naturally, these answers will most likely not be expressed, they will sound in the reader's head, but this does not prevent them from being a lively reaction of the reader to the author's question. The text thus becomes polyphonic, it "sounds" three voices (two voices of the characters and one of the author), which is joined by the voice of the reader, which is implied, because the author invites him to communicate, exchange opinions and even to argue his opinion – asks him to explain his trust / distrust of what is being said. The text, having lost most of its monologue, acquires a pronounced dialogic range.

If M.M. Bakhtin believed that the dialogization of secondary genres occurs under the influence of various types of conversational and dialogical genres, then in the modern era, the dialogical character of a novelistic text is influenced primarily by the text structure: its fragmentary composition, visual element, and other stylistics of the presentation of the topic. The generation of the "feeling of the listener as a partner-interlocutor", about which the scientist wrote, is determined precisely by these formal elements.

The analysis of the novel by D. Reno indicates that it is addressed to the reader, and not only introduces him as an active agent in the text, but also invites him to join the game. The compositional structure, in addition to the above, gives the text an interactive, playful character, responding to the request of time for communication in a game format, which also strengthens the "partner" character of the reader category.

The compositional structure revealed by D. Reno is based on components typical for a modern novel – structural blocks of different shapes and different kinds, which are constructed and used by different writers in different ways.

Thus, a feature of the structure of A. Somon's novella Je me souviens is the opposition of the font form and a large number of spaces separating specifically localized blocks:

Gaps here are replaced by the mother's remarks in a conversation with her daughter, the latter's speech therefore turns into a monologue in which she tries to justify her lover and elevate him in the eyes of her mother.

The compositional structure is "torn" into three parts: (a) the daughter's speech, (b) markers-spaces instead of mother's words, and (c) fragments from various publications related to the topic of travel.

As can be seen from the image, the visual image of the text of A. Somon differs from the image of the text of D. Reno, but this difference is not of a fundamental nature. Practically the same means of production are used in both, and they produce the same effect: the text has a discursive property, its dialogic range is determined by its structural organization. Here the reader is also involved in the text, is also a partner of the author (narrator), although in this case his participation is of a slightly different nature.

The reader's involvement, his active interest, his response to the text as an author's statement are determined by his intellectual work, which the author obliges him to do. The reader needs to perform the following actions: "fill in" the gaps in order to understand the daughter's speech, and to think out the meaning and determine the role of the fragments of publications printed in bold italics in understanding the plot. Only in this case, when implementing these actions, the story of a young woman whose life does not work out, apparently, through the fault of her mother, will form in his head. There is no story as such about her life in the text, the narrator does not narrate the story and drama of her life, and the narrator himself as the creator of the narrative about the characters is also absent.

Both in the first text and in the second, the narrator does not fulfill his main function – to narrate, to tell an interesting story that would end with an unexpected denouement. A narrative story develops in the mind of the reader, who, relying on the statements of the characters, the analysis of the compositional form and the visual image of the text, produces a story for himself independently, turning the speech of the characters (dialogue in the first case and monologue in the second) into a narrative, into a story. The new structure and visual image create new conditions for the production of the text, in which the reader acts as the creator of the story, building it as he reads in his head.

The reader of a modern French novel, thus, has turned into a "partner-interlocutor" (according to M.M. Bakhtin), moreover, he acquired the properties of a co-author / co-narrator, which the scientist did not foresee, since the literature of that era did not yet have the appropriate qualities and properties.

Conclusion

The statement of the above-mentioned and so significant changes in the novelistic text leads to the question, does the "new" text remain novelistic? Is it turning into a quasi-novel or a new genre?

It seems to us that the answer is still "yes", remains a novel, although modified, because: a) the authors of these works themselves, when they are published, most often characterize them as short stories and publish collections of short stories; b) these texts retain one of their most important classifying properties – brevity. Sometimes a modern novel becoms even shorter than a classical one, for example, A. Wurmser has published a collection in which some short stories occupy only half a page, although most of the texts still approach the classical one in volume.; c) the text in one form or another "tells" about one event, which distinguishes it from, for example, a novel and is its genre property, its generating feature.

The preservation of these fundamentally important structuring features allows the novel genre to fit into the process of hybridization of literature, although it loses no less important properties at the same time. Namely: a) the subject matter has changed: the original and amazing has been replaced, most often, by the ordinary and conventional; b) the composition of the text: the novella has a fragmentary, block structure; c) instead of perfect temporal, pronominal and adverbial forms, the forms of the present are used, d) the narrative is replaced by an utterance (dialogue, monologue), therefore, the discursive component has significantly increased, and the novel itself has acquired the properties of a unit of speech communication, which raises the problem of identifying and defining this type of utterance: a special kind of narrative? a discursive narrative? narrative discourse?; and, finally, e) the category of the reader has been modified: he has changed his passive position to an active one and today has the properties of a partner/interlocutor and/or co-author.

The new categorical properties of the reader allow us to talk about an active role of the other in the process of text formation in the French novel.

Using the logic of G. Genette’s (Genette, 1974: 68) statement on rhetoric, we can say that the genre, despite all the modifications and changes that it has been undergoing lately, is a structuring concept and successfully fits into the process of hybrization of modern literature. At the same time, it must be recognized that the genre loses some of its important properties and qualities in this cauldron of innovations.

Despite the conclusions drawn, the problem of the modern French novel as a genre remains unresolved. It is not yet possible to recognize as not essential for the typification of the genre (1) the absence in the text of coup de théâtre, an unexpected denouement, which is considered by all theorists of the novelistic genre as its cornerstone, and (2) the replacement of narrative with a discursive form, i.e. the absence in the text of the narrator, a category that, like coup de théâtre, has always been considered the main property and the main feature of narrative in general.

To solve these problems, we must wait for studies that would show the possibility of defining these changes as a free-creative re-formation of the novelistic genre or as recognition of the birth of a new artistic and literary genre.

Reference lists

Aristotle (1998). Jetika. Politika. Ritorika. Pojetika. Kategorii [Ethics. Politics. Rhetoric. Poetics. Categories], Literature, Minsk, Belarus. (In Rissian)

Adam, J-M. (2001). La généricité des textes écrits, available at: https://www.fabula.org/acta/document10985.php (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Adam, J.-M., Revaz, F. (1996). L’analyse des récits, Seuil, Paris, France. (In French)

Bakhtin, M. M. (1996).The problem of speech genres, Russian dictionaries, Moscow, Russia, 159-206, available at: http://philologos.narod.ru/bakhtin/bakh_genre.htm (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In English)

Baroche, Ch. (2007). Attention, chaud devant, nouvelles, Les Transbordeurs, Paris, France, available at: https://www.librairienouvelle.com/livre/230715-attention-chaud-devant-nouvelles-christiane-baroche-transbordeurs (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Bricco, E., Murzilli, N. (2012). Introduction, Cahiers de Narratologie, 23, available at: http://narratologie.revues.org/6639 (Accessed 20 August 2021) (In French)

Collomb, M. (1998). Figures de l'hétérogène. Actes du XXVIIè congrès de la Société française de littérature générale et comparée, Publications de l'Université Paul Valéry, Montpellier, Paris, available at: https://books.google.fr/books/about/Figures_de_l_h%C3%A9t%C3%A9rog%C3%A8ne.html?id=mz-FAAAAIAAJ (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Dugain, M. (2000). La Chambre des officiers, Poche, Paris, France. (In French)

Evnina, E.M. (1976). Maupassant and his stories, in de Maupassant G., Contes et nouvelles, Editions du Progrès, Moscow, USSR. (In French)

Fleutiaux, P. (2016). Destiny. éd. Actes Sud, Paris, France. (In French)

Fleutiaux, P. (2015). Lire, vivre et rêver, Les Arènes, Paris, France. (In French)

Genette, G. (1974). Figures. T3. Editions du Seui, Paris, France. (In French)

Goyet, F. (2003). Des Nouvellistes entre deux formes: La Nouvelle au tournant du XXe siècle, in El relato corto francès del siglo XIX y su recepcion en España, Conception Palacios Bernal (ed.), Universidad de Murcia, 167-190, available at: http://ouvroir-litt-arts.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/revues/reserve/262-des-nouvellistes-entre-deux-formes-la-nouvelle-au-tournant-du-xxe-siecle (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Galperin, I.R. (1977). Grammatical categories of the text, Izvestia of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 36 (6), available at: http://feb-web.ru/feb/izvest/1977/06/522.pdf (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In English)

Iskhakova, O.S. (2017). Historical prerequisites for the study of speech genres, European research, 3 (26), 41-43, available at: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/istoricheskie-predposylki-izucheniya-rechevyh-zhanrov (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In Russian)

Lotman, Yu.M. (1970). The structure of a literary text, Publishing House Art, Moscow, Russia, available at: https://imwerden.de/pdf/lotman_struktura_khudozhestvennogo_teksta_1970__ocr.pdf (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In English)

Macé, M. (2001). La généricité restreinte, Acta fabula, 2 (2), available at: http://www.fabula.org/acta/document10985.php (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Paterson, J.M. (2001). Le paradoxe du postmodernisme, in R. Dion, F. Fortier et E. Haghebaert, L'éclatement des genres et le ralliement du sens, Éditions Nota bene, Québec, 91- 114, available at: https://www.fabula.org/actualites/enjeux-des-genres-dans-les-ecritures-contemporaines_2254.php (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Petrenko, T.P., Kotliarevskaia, I.Y., Tambieva, F.A. and Airapetov G.E. (2021). Digital Technologies in Literary Work as a Modern Way of Visualizing Socio-economic Phenomena, in Popkova E.G., Sergi B.S. (eds), Modern Global Economic System: Evolutional Development vs. Revolutionary Leap. Springer, Cham, 1384-1393, available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-69415-9_153 (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In English)

Potvin, C. (2001). De l'utopie féministe comme genre littéraire, in R. Dion, F. Fortier et E. Haghebaert, Enjeux des genres dans les écritures contemporaines, Éditions Nota bene, Québec, 71 - 90 (available at: https://www.fabula.org/acta/document10985.php (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Saumont, A. (2012). La guerre est déclarée et autres nouvelles, Poche étonnants classiques, Paris, France. (In French)

Saint-Jacques, D. (2001). Le renversement d'une hégémonie. les genres de la culture médiatique et la littérature, in R. Dion, F. Fortier et E. Haghebaert, Enjeux des genres dans les écritures contemporaines, Éditions Nota bene, Québec, 25-37, available at: https://www.fabula.org/acta/document10985.php (Accessed 20 August 2021). (In French)

Zima, P.V. (2001). Vers une déconstruction des genres ? à propos de l'évolution romanesque entre le modernisme et le postmodernisme, in R. Dion, F. Fortier et E. Haghebaert, Enjeux des genres dans les écritures contemporaines, Éditions Nota bene, Québec, 11-24, available at: https://www.fabula.org/acta/document10985.php (Accessed 20 August 2021). (InFrench)