Terminology vs phraseology: meaning transfer in business terms

Abstract

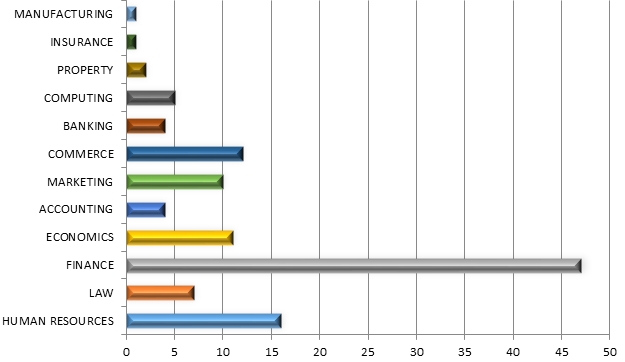

The research is aimed at the study of Business English terminology of phraseological character, i.e. at the study of Business English terms based on a kind of meaning transfer thus acquiring a kind of phraseological meaning. As a result of the PU-terms semantics examination, coupled with private-paradigmatic methods for analysing their dictionary definitions and contextual usages recorded in the BNC and COCA, I found out the quantitative correlation of Business English PU-terms with a full meaning transfer and those with a partial meaning transfer. Among the latter, I identified two subtypes of the incomplete semantic transfer of the PU-term component composition and assign the following terms to them: an evident partial shift of meaning and a non-evident partial shift of meaning in the components. Another result of the study, presented in the text of the paper in the form of a bar graph, is the clarification of the nomenclature of the most active business English domains that operate with business PU-terms. Extensive linguistic material of the study, the proven method of phraseological identification introduced by A. V. Kunin, and reliable methods of phraseological analysis and phraseological description have made it possible to obtain essential results. Conclusion: the work proves the progress of the recent English terminology according to the phraseological scenario and provides language material for the typological study of the PU-terminology.

Keywords: Terminology, Phraseology, PU-terms, Component, Phraseological Identification, Meaning transfer

Introduction

A. The scientific background of the research

The object of the research is business English terminology of different domains (Fedulenkova, 2015) as it is given in the entries of LONGMAN Business English Dictionary edited by Michael Murthy in the second decade of the new Millenium[1] and a set of other modern issues.

The subject of the research is (a) to find out the PU-terms that appeared due to full transfer of component meaning, (b) to find out the PU-terms that appeared due to partial transfer of component meaning and (c) to fix the percentage interrelationship between both the groups of terminology of phraseological nature

The associated objectives of the study are as follows:

1) to find out the quantitative correlation of Business English PU-terms with a full meaning transfer and those with a partial meaning transfer; 2) among the latter, to identify two subtypes of the incomplete semantic transfer of the PU-term component composition and assign the corresponding terms to them; 3) to present the result of the study in the form of a bar graph, as the clarification of the nomenclature of the most active business English domains that operate with business PU-terms.

To achieve the research target a number of innovative ideas in the sphere of phraseological and terminological theories and methods were employed in the process, namely: Alexander V. Kunin’s method of phraseological identification (Kunin, 1996: 38-43), Vladimir M. Leichik’s terminological theory (Leichik, 2009: 143) and Anthony Paul Cowie’s ideas on contextual phraseological studies (Cowie, 1998: 210; 2000). The idea of the corpus compilation method was partly borrowed from Attapol Khamkhien and Sue Wharton (2020: 16‒17) as well as some other new methods in phraseological studies were referred to (Simpson-Vlach & Ellis, 2010: 487).

The study is also motivated by urgent pragmatic needs for preparing business vocabulary for the ESP classroom (Tangpijaikul, 2014; Fedulenkova, 2021b), taking into consideration the so-called ‘holistic’ nature of ‘formulaic language’ (Schmitt, 2004; Siyanova-Chanturina, 2015; Wood, 2015; Peters & Pauwels, 2015) and the academic requirements in developing Business English competences (Ayto, 1999: 3-10; Murthy, 2007: 6-9) alongside with the study of key concepts in information and communication technology (Cartwright, 2005; Tuck, 2000), with the view of their patterning and pragmatic functions (Fedulenkova, 2016; 2019a).

Besides the study (as well as a number of other works published) is motivated by the practical needs of compiling a manual for undergraduates on Business English Phraseology.

The novelty of the research consists primarily in the following:

a) the interrelation of Business English terminology, on the one hand, and English phraseology, on the other hand, has not been studied yet,

b) the status of business terminological set expression as referred to phraseology has not been defined yet,

c) no subtypes of the incomplete semantic transfer of the PU-term component composition have been found out and no corresponding terms have been assigned to them.

The study of terms of a phraseological nature is relevant, because a significant part of the new terms in the field of business language is formed according to the phraseological model of transfer the semantics of a prototypical word-combination. That problem is tackled in the paper with the view of V. D. Arakin’s explanation of the cause in the typological change of English (see below).

B. The cause of idiomatisation in terminology

It is not a rare occasion to encounter some arguments against idioms in modern English, with their authors insisting on that idioms, as well as phraseological units of other kinds, are some bizarre language units and are undoubtedly out of use because of their deeply archaic nature and obsolete character.

The value of those arguments seems to be rather problematic. The proof of that is in the fact that modern English mainly develops due to such mechanism of nomination as a metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson, 2003). A mere scanning of John Ayto’s dictionary Twentieth Century Words reveals the fact that nearly half the volume contains entries dealing with new words and set expressions that have appeared in English for the last hundred years through some transfer of meaning based on metaphor, metonymy, hyperbole, litotes, and the like, especially in two-component set expressions (Fedulenkova, 2021a: 114).

All of those new items of metaphorical/ idiomatic nomination are characterized by high frequency in business discourse (see also: (Stubbs, 2007: 89)). One can easily see it on having scanned the BNC tables at random which reveals the fact that, for instance, the PU-term shadow cabinet is supplied by 196 contexts, the PU-term black market is supplied by 157 contexts, the PU-term Big Bang is supplied by 355 contexts; and, to prove their professional power in business communication, here there are some of them[2]:

(a) This is certainly true of the subject groups. When the Conservatives are in opposition, the frontbench spokesman on each subject area is also chairman of the parallel party group, thus providing a direct channel of communication between backbench opinion and the Shadow Cabinet. Naturally, when Conservatives are in office, the opportunities for meetings between backbenchers and party leaders are more restricted. They also vary greatly depending upon the attitudes adopted by individual ministers.

(b) If firms believe devaluation is likely in the near future, they typically defer investment until after the event, to avoid writing down the asset value. A prime indicator of future trends in many countries that attempt to manage the rates is the black market rate. For example, unlike Brazil, Myanmar insists that all multinationals’ currency dealings are at the official rate. With the black market standing at roughly one-tenth of the official rate in mid-1990, many investors who might otherwise have wanted to invest were holding back, betting that the official rate could not indefinitely be propped up. The second factor is how the government intervenes to affect the exchange rate. Kenya’s practices illustrate the problem.

(c) With the growth of financial conglomerates, in particular the merging together of banking and securities business, problems have inevitably arisen. As stated in chapter one, these problems revolve around the safety and soundness of the financial system and, more importantly for our purposes, conflicts of interest and duty. Conflicts of both interest and duty are not new to the City of London; indeed, they have traditionally been of great concern to financial market regulators. What has happened, however, is this that the advent of Big Bang, and the consequent emergence of one stop financial conglomerates, has exacerbated the problem of conflicts of interest and duty and placed added burdens on the ability of legislation (albeit newly designed) to cope with potential abuses. A conflict of interest occurs where, for example, a market operator’s interest potentially conflicts with that of a client (conflict of interest), or where a market operator owes obligations to two or more clients who’s interests might well pull in different directions (conflict of duty).

“Highly technical discourses, ‒ as Chitra Fernando puts it, ‒ whether written or spoken, such as those belonging to the registers of mathematics or physics or symbolic logic may seem to be candidates for neutrality, but even these typically argue a thesis to prove or disprove a theory and therefore embody evaluation” (Fernando, 1996: 138). Maintaining the author’s idea one might agree to her statement that “appraisals in this type of discourse may emerge more strongly at the global text level” (Fernando, 1996: 139). Though, it is not the emotion only that urges idiomaticity. It is development of a matter-of-fact language, especially in the field of business, finance and economics, that demands thorough penetration into the issue (Tangpijaikul, 2014).

The flourishing effect of metaphoric mechanism in the process of nomination might be elucidated by the lack of morphological means for the purpose of naming new things and phenomena that naturally and constantly appear in the extra-linguistic world. Interestingly, that lack happened because of the drop of the third suffix, or stem suffix, in the pre-historic time of Old English ‒ that fact was already obvious in the Gothic manuscripts ‒ which caused the change of the English language type from a synthetic to analytical one, as it was brilliantly proved by Vladimir D. Arakin in his monograph on comparative typology (Arakin, [1979] 2005). Incidentally, the fact was totally missed by European scholars (Stockwell & Minkova, 2002) who managed to only register the sequence of changes in the language vowels but unluckily failed to notice its typological effect and to supply any arguments for that (Blake, 2005; Fennel, 2004). To say nothing of the specialists in phraseology who, having paid much effort to various mechanisms of semantic transfer giving birth to phraseological units, managed to ignore the basic cause in the English language evolution (Moon, 1998; Cserép, 2008; Ziem & Flick, 2018), though some of them penetrated deeply into the origin of the term ‘phraseology’ (Autelli, 2021), took much effort to draw linguists’ attention to PU stylistic and contextual use (Naciscione, 2010; Cowie et al, 2000) and even touched upon the cognitive aspect of the phraseological processes in nomination (Erman, 2007). Unluckily, none of the paternal researches has ever paid attention to the problem (Ponomarenko, 2007; Pashchenko, 2018).

In the meantime, due to globalization, and to the efforts of the researches and lexicographers to meet the requirements of business in new terms and their pragmatic adequacy, quite a succession of special dictionaries appeared embracing business terminology. Primarily, the researcher’s penetrating eye is to be drawn to such reliable defining dictionaries as a dictionary containing 4100 entries by Brian Butler et al.[3], Allene Tuck’s dictionary of Business English with over 5000 entries[4], The New Penguin BusinessDictionary edited by Graham Bannock et al.[5], LONGMAN Business English Dictionary with 30000 up-to-date business terms edited by Michael Murthy[6], Jonathan Law’s edition with over 5100 entries[7], The PenguinDictionary of Marketing including approximately 2000 entries and edited by Phil Harris[8], John Pallister & Allan Isaacs’s reliable edition including 7000 entries[9].

Each of those dictionaries presents an abundance of new and unique terms of idiomatic nature that have started their life in the world of business, management and finance, and here there are only a few samples: time bargain, wash sale (Butler), chain store, kite mark (Tuck), marginal utility, sleeping partner (Bannock), kanban system, quality circle (Murthy), repackaged security, salvage value (Law), Wilcoxon test, zero-sum game (Harris), kamikaze pricing, marketing myopia (Pallister & Isaacs) and many others, shocking an unsophisticated mind with their fresh metaphors.

C.Discourse activity of idiomatic terminology

The intensive use of idioms in the sphere of terminology is quite evident now, and the evidence is especially eloquent ‒ during the last few decades ‒ in the field of business terminology where a great many business terms appear by means of a kind of semantic transfer in their prototypical word-combinations (Fedulenkova, 2019b; 2021b).

For instance the business term golden handshake first fixed in 1960 is used as a term in the sphere of human resources in the meaning having to do neither with a handshake, nor with the metal mentioned, and defined as ‘a gratuity given as compensation for dismissal or compulsory retirement’ and followed by the illustration: “1960 Economist: There is little public sympathy for the tycoon who retires with a golden handshake to the hobby farm”[10]. A bit more detailed definition of the PU-term meaning is found in LBED that reads as follows:

golden handshake ‒ ‘a payment made by a company to a director, senior executive, or consultant who is forced to retire before the expiry of a service contract, as a result of a merger, takeover, or any other reason; <…> this form of severance pay may be additional to a retirement pension or in place of it; it must also be shown separately in the company’s accounts, because these payments can be very large <…>’[11].

The intensity of the term use is illustrated by the three out of the total 24 BNC contexts, e.g.[12]:

- Over years, the courts have adopted varying approaches. One possibility is to ignore the part of the award of damages which exceeds the amount exempt from tax under the ‘golden handshake’ rules, for instance by expressing the exempt amount <…>.

- <…> taking into account that he would have paid income tax on earnings, then adding back ‘golden handshake’ tax so that he would be left with the net amount after the Revenue had collected tax on the damages.

- Sir Nicholas stressed that the golden handshake was not ‘hush money’, adding that the resignation had been mutually agreed following restructuring talks. The payment resulted from the fact that his three-year contract had some time to run.

Evidently, the spheres of use of the term golden handshake concern advice (a) on how to get the best deal from your employer, (b) on how to avoid extra income taxes, (c) on how to behave in order not to become a victim of criminal prosecution under the circumstances, i.e. advice on most urgent issues of the day in business routine life.

Besides, inspired by ‘golden handshake’, a number of terms gathering under the same ‘golden’ umbrella did not hesitate to enter business communication later on, namely: in 1976 ‒ golden handcuffs, in 1981 ‒ golden parachute and in 1983 ‒ golden hello. Let us have a closer view of their semantic value:

- golden handcuffs is defined as ‘benefits (e.g. a private health scheme or a company car) provided to employees in order to induce them to remain in their jobs and not move to another company’ and illustrated as “1982 Wall Street Journal: Getty Oil is trying to lock ‘golden handcuffs’ on explorationists by offering them four-year loans ‘up front’ equal to 80% of an employee’s salary”[13];

- golden parachute is defined as ‘a long term contractual agreement guaranteeing financial security to senior executives dismissed as a result of their company being taken over or merged with another’ and illustrated as “1990 New York Times Book Review: It was not long before most of the RJR Nabisco’s top executives ‘pulled the rip cords on their golden parachutes’… Mr Johnson’s alone was worth $53 million”[14];

- golden hello is defined as ‘a substantial sum offered to a senior executive, etc., as an inducement to change employers, and paid in advance when the new post is accepted <…>’[15].

The broad use of those PU-terms may be illustrated by the numerous BNC contexts, e.g., as follows:

(a) The announcement only fuelled speculation that he is earmarked for greater things in the Shandwick organisation, <…>, or even that he was preparing the way for something completely different when his five-year golden handcuffs are released next year.

(b) Many of us suspected that it was John’s mismanagement of the organization that had gotten the company into trouble and caused us to have to lay off so many of our co-workers. The grand finale, however, came later that afternoon when the evening paper reported John’s resignation, as well as the payment of a $ 4 million golden parachute.

(c) This amount includes fees, taxable expense allowances, pension contributions, benefits in kind and amounts paid to obtain the services of a director (“golden hello”). Analyse the amount between payments: for services as director of the company, <…>.[16]

As far as one can gather, all the three terms under discussion deal with a good sum of money paid to a wanted employee before or after his work with the view of making use of one’s talent and creative activities in the field.

The contexts illustrating newly formed terminology of phraseological nature reveal that new business and corporative needs have led to new social relationships that are not at all welcome by fair competition as it is exposed in the following statements:

(a) The concern for the people for whom you are responsible by being given a position of influence and power and authority has gone. The Golden Handshake, the Golden Hello and Big Bang and the whizz kids have changed all that.

(b)The Big Bang has certainly encouraged the trend towards offering Golden Handcuffs ‒ to maintain the Golden Hellos ‒ and the insertion of exclusion clauses in contracts to prevent executives going over to the competition.[17]

Main part

Discussion of the research result

While undertaking research in the field of Business English terminology I focus my analysis on those terms that are characterized by a two-component structure. And here the attention of the researcher is drawn to the fact that a great many terms are characterized by a semantic transfer, i.e. the total component meaning of the prototypical word combination does not reveal the meaning of the resulting term, which argues for the fact that the terms under study are undoubtedly idiomatic expressions and therefore they undoubtedly belong to the sphere of phraseology.

1. Full meaning transfer as basis for PU-terms

Semantic analysis of business terms having phraseological nature (we call them PU-terms) is employed to differentiate (a) those PU-terms the appearance of which as signs of nomination was caused by full transfer of word/ component meaning in the prototypical word-combination, and (b) those PU-terms the appearance of which was caused by partial transference of component meaning in the prototypical word-combination. In the course of the semantic analysis it is reasonable to rely, first of all, upon the definitions supplied by the dictionary entry and try to focus one’s attention on the availability of any words in that very definition that co-inside in form and meaning with at least one component of the PU-term under discussion. In case no such coincidence is observed, the PU-term is thought to be a phraseological unit with full transference of meaning, i.e. while being able to realize the meaning of every PU-component one cannot guess the total meaning of the PU-term, e.g.:

(1) black knight FINANCE ‒ ‘a company that tries to take control of another company by offering to buy large numbers of its shares: While not particularly welcome the black knight is considered more favourably than the hostile bidder’[18], e.g.:

<…> An alternative offeror which the target company is prepared to recommend to its shareholders in preference to a hostile bidder. While not particularly welcome, black knight is considered the lesser of two evils <…>[19].

(2) boiler room FINANCE ‒ ‘an organization selling investments by telephone using unfair and sometimes dishonest methods’[20], e.g.:

It is a psychologically unrewarding task for the person soliciting over the telephone, and this is <indicated by> the vernacular term applied to the location from which such solicitation takes place ‒ ‘theboiler room’. Insofar as the UK is concerned, very little of this activity takes place at end consumer levels, but its use has increased in industrial markets in support of sales, especially in relation to the following: # (i) # Initial contacts with potential customers with a view to a follow-up sales call. Such contacts can be obtained from trade directories, visitors to an exhibition stand, members of a particular group (e.g. professional body or attendees at a conference); # (ii) # Stock replenishment for established customers when an enquiry can be made about a re-ordering possibility <…> [21].

(3) business angel FINANCE ‒ ‘a private investor who puts money into new business activities, especially ones based on advanced technical ideas: In the UK, business angels are a more important source of investment for start-ups than venture capital funds’[22], e.g.:

As both company chairman and business angel, Sir John plays an active role. He and Ivan are equal partners. <…>. The fifty percent shareholding has worked well, because what it means no one person can impose their will, no one has control, you have to resolve problems by agreement, resolve disagreements without coming to blows. <…> Angels don’t always work miracles…[23].

(4) blue chip ‒ ‘colloquial name for any of the ordinary shares in the most highly regarded companies traded on a stock market <…>. Blue-chip companies have a well-known name, a good growth record, and large assets; the main part of an institution’s empty portfolio will consist of blue chips <…>’[24], e.g.:

“HOARDING STACKS OF SHINY METAL IS NOT INVESTING!! Investing is something that takes time and consideration, and many years of painstaking research. Retail investors should only be investing in blue chip companies with proven records of success, and these investments should only be made under the guidance of a professional stock broker or financial advisor. Buying gold bullion is not only an esoteric and dangerous ‘investment’, but it also runs contrary to the opinion of some of the world’s most respected an accomplished investment professionals. # You are using the word ‘investing’ much like Krugman uses the word ‘economics’. In theory, it works <…>.[25]

(5) dawn raid STOCK EXCHANGE ‒ ‘a surprise attempt to buy a large number of shares in a company in the first minutes of a day’s business in the stock exchange, before dealers can react by raising prices: mount a dawn raid in the shares of an international company’[26], e.g.:

<…> lecturing on the essential point of the ‘up-date’ key notion <…> a swift operation effected early in stock-market trading whereby a stockbroker obtains for his or her client a markedly increased shareholding in a company (often preparatory to a take-over) by clandestine buying from other substantial shareholders, as in Bookseller: Following his ‘dawn raid’ last July, which gained him 29,4 per cent of BPC, Robert Maxwell <…> and clearly plans to secure and consolidate his control of the ‘grasp’ <…>.[27]

Evidently, all the five terms under analysis are idioms because one does not see their meaning before reading their dictionary definitions or the contexts the terminological expressions are used in.

2. Fully transferred PU-terms domains

Fully transferred PU-terms may belong to a variety of domains serving business communication, namely:

A. Accounting

current ratio ACCOUNTING ‒ ‘the relation of the current assets of business to the current liabilities, expressed as ꭓ:1 and used as a test of liquidity’[28], e.g.:

In an essay published in the New Statesman in June, Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, criticized the government’s austerity policy, saying it was unnecessary as the current ratio of public debt to GDP is much smaller than in the two decades after the Second World War, when it caused little panic.[29]

B. Banking

discount window BANKING ‒ ‘a method by which a central bank supplies a banking system with short-term funds, either by purchasing Treasury bills or by making secret loans’[30], e.g.:

The discount houses, facing the shortage which was created in the money market, were forced to borrow from the Bank of England’s discount window at Bank Rate. From the mid-1970s onwards greater reliance was placed on control of broad money and sales of gilts replaced the need for the government to finance its borrowing requirement through the issue of Treasury bills. Indeed, the money market shortages created by greater reliance on sales of gilts were initially relieved by buying back Treasury bills from the market.[31].

C. Finance

triple witching alsotriple-witching hourinformal FINANCE ‒ ‘a time on a financial market when futures, stock index futures, and stock options all expire (=reach the end of their life) at the same time: Friday’s triple-witching hour will see three sets of options and futures contracts expire on the German Futures and Options Exchange’[32], e.g.:

<..> Falling interest rates and cheaper share prices brought investors back to the stock market. Steve Young reports from New York, <…> CNN Business News: <…> voice-over The night before Christmas, what should appear but an advance so broad it embraced most industries. Analysts said investors cautious Friday because of triple witching options expirations, came back with a vengeance. JACK SOLOMON, Chief Technical Analyst, Bear Stearns: Right now was the most abrupt drop in interest rates that we’ve seen in about two decades or more. Bonds have gone sky high, and in bonds going sky high, it makes the yield on stocks competitively more attractive. [33]

D. Human resources

mission creep HUMAN RESOURCES ‒ ‘a series of gradual changes in the aim of the people who manage a company or organization, with the result that they do something different from what they planned to do at the beginning: The penalty clause in the contract leaves no room for mission creep’[34], e.g.:

The solution is to defund the left, entrenched in government. The greens sue their buddies in government for every increasing power and control. The solution is to drop the grants and mission creep which is pandemic in the environmental movement. We need an EPA, but not in it’s present metastasized organization. Their secret papers, the scientific basis for their regs, must be exposed. The grants that only go to leftist scientists must be shut off, with equal funding going to those who hold differing scientific judgments. The economic studies justifying their regs must be divulged. We need sunlight <…> for <…> green growth. And we need to restore trust in government. # Basically we need to restore professional technical authority in both government and the private sector.[35]

E. Law, Insurance act of God INSURANCE ‒ ‘a natural event that is not caused by any human action and cannot be predicted <…> however, some contracts exclude liability for damage arising from acts of God’[36], e.g.:

<…> shall not be under any liability to <…> any party in any way whatsoever for the destruction, damage, delay or any matters of this nature whatsoever arising our of war, rebellion, civic commotion, strikes, lock-outs and industrial disputes; fire, explosion, earthquake, act of God, flood, drought, or bad weather; the unavailability or deliveries, supplies, work, disks, or other media or the requisitioning or any other act or order by any government department, council or other constituted body.[37]

F. Marketing

empty nesters MARKETING ‒ ‘a term commonly used to describe middle-aged or older couples whose children have grown up and ‘left the nest’ to live on their own’[38], e.g.:

# Condos are popular with homeowners who don’t want or need a lot of space and landscape to take care of, from singles to young marrieds to empty nesters. Usually smaller than a detached home, condos can present challenges in decorating. Their small size is to be thought of while deciding on a room’s furnishings. Small, however, doesn’t have to mean cramped and uninviting. You may have to make some sacrifices, but it is possible to create a stunning living room in very little space. #[39]

G. Statistics, Finance

random walk STATISTICS ‒ ‘refers to the theory that prices on a financial market move, for whatever reason, without any memory of past movements and the movements therefore follow no pattern’[40], e.g.:

The assumptions underlying the binomial approach can be summarized as follows: # 1. # Perfect capital markets with no taxes or transactions costs. # 2. # Information is costless and universally available. # 3. # Short sales permitted; # 4. # Share prices follow a random walk without any underlying trend. # 5. # The risk-free rate is constant over the life of the option. # 6. # No dividends. # 7. # A one-period time horizon. Assume that at the exhaustion of the investor’s time horizon there are two possible end states, <…>.[41]

3. Partial meaning transfer as basis for PU-terms

3.1. Partial meaning transfer of type 1

As to partial shift of component meaning in a terminological set expression, it may be of two types. Partial meaning transfer of type 1 is clearly revealed through the dictionary definition that accompanies a terminological set expression in its corresponding dictionary entry. Here I follow the rule: if the wording/formula of the definition repeats at least one word of the terminological set expression, it proves that the latter is a language unit of a phraseological nature having an evident partial shift of component meaning, с.f.:

a) standstill agreement FINANCE ‒ ‘in an unwanted takeover, an agreement between a company and the bidder (=someone trying to take control of it) in which the bidder agrees not to by any more shares in the company for a particular period of time in return for more power on the board etc.: It signed a standstill agreement under which it promised not to increase its holding for three years’[42];

b) buzz group MARKETING ‒ ‘one of several small groups of people that a bigger group is divided into, in order to discuss what they think about a subject, for example a training course: Buzz groups are an excellent way of promoting discussion during training sessions’[43];

c) sitting tenant PROPERTY – ‘a tenant who has the right to continue to live in a property or part of it, when it is sold to a new owner: She bought the house very cheap because it had sitting tenants’[44];

d) depressed market COMMERCE ‒ ‘a market where there is little demand for the products and services offered for sale: Many traders are suffering because of the depressed market’[45];

e) splash page COMPUTING ‒ ‘a preliminary page that precedes the normal home page of a website; <…> site users can either wait to be redirected to the home page or can follow a link to do so’[46]; etc.

Here are some contextual examples ‒ for d) and e) ‒ that confirm the phraseological meaning of the term having resulted in an evident partial semantic shift:

d) # The continuing slide in California home prices, the longest in more than a half-century, is dragging down the rest of the state’s economy in a vicious spiral. # Housing prices across the state dropped an average of 12 percent from mid-1990 to early 1993 and are still falling, according to Regional Financial Associates in West Chester, Pa. The decline in values is hitting people who bought near the peak, who try to take out home equity loans or whose inflated estimates of their net worth are being dashed by depressing real estate stories. # As a result, the depressed market for homes is throwing the California economy at least four punches <…>.[47]

e)Splash pages are a wonderful way to show off the best work you can create, and hence also act as a portfolio of your work and operate capacity for potential employers. As the splash page states the technical requirements necessary for their certain web site, it allows the reader to pick, prior to visiting the web site, the technology that finest fits them and their computers. It is also a fantastic means of making use of your server logs to get the complete breakdown of the actual number of consumers to the website. <…>. The cons to splash pages are not that a lot of or main. It is only that some readers do not like splash pages as it prevents them from entering the site instantly, and therefore might leave the internet site upon seeing the splash page.[48]

3.2. Partial meaning transfer of type 2

To find out partial meaning transfer of type 2 it is necessary to scan the definition and to look for either synonymous words for the components of the term under analysis or for words pertaining to the identic thematic group or field. And in case at least one of the term-component synonymous to a word in definition or belongs to its thematic group or field, then it might be called non-evident, partial semantic shift of component meaning. To see it, let us compare the semantic/ thematic fields of the words registration and record, income andmoney, doctor and someone, audit and examination, cash and money, e.g.:

a) shelf registration FINANCE, LAW ‒ ‘the allowance that, since 1983, larger companies may officially record advance details of securities with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) without any date of issue so that when they need to raise capital they make an issue ‘off the shelf’ without the delay involved in waiting for clearance of an application to the SEC[49];

b) transfer income ECONOMICS, FINANCE ‒ ‘money received from the government in the form of pensions, unemployment benefits, farming subsidies, etc.; it is not payed for goods and services, but is transferred by means of taxation from one group of people to another’[50];

c) company doctor ‒ ‘someone with special knowledge and experience who is employed to help a business that is losing money and which may have to close: The ailing engineering firm has called in a company doctor after shedding 90% staff’[51];

d) green audit ECONOMICS, FINANCE ‒ ‘an internal or external examination of the impact of the activities of an organization on the environment [which] purpose is usually to ensure that the organization has clear environmental policies <…>’[52];

e) cash mountain [usually singular] FINANCE ‒ ‘money that a company has available to spend, for example to buy other companies, or to give to shareholders: The group’s cash mountain has shrunk’[53]; etc.

Here are some contextual examples ‒ for d) and e) ‒ confirming the phraseological meaning of the term as the result of a concealed partial semantic shift:

d) Erin Porter did an environmental audit of the photography tab at her Pittsburgh High School as part of her environmental club’s schoolwide green audit for Earth Day 2000. Porter searched to see: Is the fixer recycled? Are chemicals properly handled? “The teacher was slightly hesitant at first,” says Porter. But for naught. If the green survey were a report card, she says, the lab would get an A. What Porter really noticed, however, was how she started to view chemicals back home. Now, she says, I’m much more conscious of what I’m dumping down the sink. [54]

e) <…> Despite its cash mountain, South West is still generally seen, perhaps unfairly, as the least attractive of the authorities and privately the Government is worried about its flotation prospects. The Camelford pollution incident, coupled with the bungled appointment of a new finance director, has contributed to an impression of management incompetence.[55]

3.3. Partially transferred PU-terms domains

The semantic and quantitative studies show that alongside with terminological word combinations having transparent meaning (i.e. having no signs of semantic transference of components), terminological set expression based on partial shift of component meaning are actively employed in the following domains serving business communication:

A. Accounting

day book ACCOUNTING ‒ ‘an account book in which goods and services bought on credit and sales are recorded: Any purchase invoices should be checked and entered into the purchases day book and the ledger’[56], e.g.:

# Special functions # If the establishment has substantial special function business, e.g. banquets, weddings, dances, dinners, conferences, etc., it is usual to open a separate special functions day book which is posted to a composite special functions debtors account in the ledger.[57]

B. Banking

floating rate also variable rate BANKING ‒ ‘an interest rate that can change during the life of the loan: CB is trying to substitute floating rate for fixed rate mortgages in France’[58], e.g.:

The net effect will be to eliminate the currency flow surplus. The demand curve for sterling will shift to the left and the supply curve will shift to the right until they intersect at the fixed rate of exchange. At that point the money will stop rising (at least from this source). Under a totally free floating rate, total currency flow surpluses will be eliminated by an appreciation of the exchange rate.[59]

C. Commerce

sunset industry COMMERCE ‒ ‘<…> often contrasted with sunrise industry and denotes an old, dying industry such as ship-building, but that term has not stayed the course so well’[60], e.g.:

<…> Mr Harrison said: ‘Following the closure of the Swan Hunter yard the Government has finally agreed to talk to the EC about getting the same subsidies for all British shipyards that we’ve been giving to our competitors in the EC for years. ‘Shipbuilding isn’t a sunset industry. It’s quite clear from papers issued by the EC that in the medium and long term shipbuilding is more than a viable industry it will grow and prosper. ‘In 10 years’ time Cammell Laird could be closed and yards in France and Spain could be on the crest of a wave because they retained their shipbuilding capacity.’[61]

D. Economics

invisible exports [plural] ECONOMICS ‒ ‘exports such as financial services that are not physical goods or products: Selling insurance overseas is one of Britain’s largest invisible exports’[62]; e.g.:

Since then we have had Polly Peck, Brent Walker, the scandal of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, and then the greatest scandal of all ‒ the Maxwell scandal. As self-regulation is proving somewhat less than satisfactory, is it not time to consider establishing a Securities and Exchange Commission ‒ SEC ‒ as exists in America? The City of London is important to the invisible exports of this country, and we cannot allow scandals such as those that have happened in the past.[63]

E. Finance

standstill agreement FINANCE ‒ ‘in an unwanted takeover, an agreement between a company and the bidder (=someone trying to take control of it) in which the bidder agrees not to buy any more shares in the company for a particular period of time in return for more power on the board etc.: It signed a standstill agreement under which it promised not to increase its holding for three years’[64], e.g.:

<…> In addition, the company confirmed yesterday it defaulted on an $800m Eurobond issue secured by a tower in Manhattan’s World Financial Centre. O &Y; failed to make a $62m interest payment on the issue despite a 20-day grace period and is trying to negotiate a standstill agreement. O &Y; has also missed a C$450m principal payment on Toronto’s Scotia Plaza development and a $100m principal payment on a New York property. Negotiations continued yesterday in Toronto between the company and various groups of creditors.[65]

F. Marketing

diffusion process MARKETING ‒ ‘<…> the process by which a new idea or product is spread accepted and assimilated within a market or industry[66], e.g.:

# The Telecommunications Act of 1996, the first major telecommunications law reconstruction since 1934, possibly helped accelerate the process of accessibility. <…> Critical disadvantages may evolve during the years that it takes for technologies to trickle down to those at the end of the diffusion process. For example, while most homes in the United States had telephones by the mid-1960s, the high cost of phone connections on tribal lands still prohibits many citizens living on reservations from having basic telephone services even today.[67]

The analysis undertaken reveals about a dozen of business domains gathering idiomatic terms, the most powerful among them are the domains of FINANCE, HUMAN RESOURCES, COMMERCE, ECONOMICS and MARKETING. The whole ratio picture is presented in the bar graph below.

Figure. Percentage relations of basic Domains embracing PU-terms based on meaning transfer

Conclusion

The study was mainly urged by the two problems in modern linguistics and lingo-pragmatics, i.e.: a) the issue of interrelation of terminology and phraseology and the necessity to define the status of business terminological set expression as referred to phraseology, and b) the issue of pragmatic value of business terminological phraseology in ESP, which were successfully solved in the research.

The following associated objectives of the study have been achieved:

1) the quantitative correlation of Business English PU-terms with a full meaning transfer and those with a partial meaning transfer have been established; 2) among the latter, the two subtypes of the incomplete semantic transfer of the PU-term component composition have been found out and the corresponding terms have been assigned to them, namely: an evident partial semantic shift of component meaning and a non-evident, or concealed, partial semantic shift of component meaning; 3) the result of the study in the form of a bar graph has been presented, as the clarification of the nomenclature of the most active business English domains that operate with business PU-terms.

The analysis based mainly on definitions and contexts gives the opportunity to establish the interrelation of terminology and phraseology and define the status of business terminological set expression as referred to phraseology in the following way:

- about 38% of business terminology fixed in modern Business English dictionaries is of phraseological nature;

- one third of the phraseological business terminology belongs to idioms, i.e. to phraseological units having full transfer of component meaning, and

- the rest of it belongs to phraseological unities, i.e. to PU-terms having partial transfer of component meaning, which in its turn may be differentiated between:

(a) PU-terms being the result of an evident partial semantic shift of component meaning and embracing about 32,7% of the PU-terms under study, and

(b) PU-terms being the result of a non-evident, or concealed, partial semantic shift of component meaning and embracing about 67,3% of the PU-terms under study.

The perspective studies are seen in the following:

(a) in structural and quantitative analysis of terminology of phraseological nature presented in the recent English-Russian business dictionaries edited by paternal specialists in the field under study (such as B. G. Fedorov, L. N. Eskin and a number of other innovative authors[68]),

(b) in typological studies of PU-terms.

The pragmatic perspective of the research lies in the collective compiling a manual for undergraduates on Business English Phraseology, which obviously suggests the practical significance of the work.

[1] Murthy, LONGMAN.

[2] BNC = British National Corpus, available at: http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/ (Accessed 15 December 2021). (Hereinafter, the spelling and punctuation of the cited source are preserved. – T.F.)

[3] Butler, B., Butler, D. and Isaacs, A. (1997). A Dictionary of Business and Finance (from international to personal finance), Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

[4] Tuck, A. (2000). Oxford Dictionary of Business English (for learners of English), Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

[5] Bannock, Gr., Davis, E., Trott, P. and Uncles, M. (2002). The New Penguin Business Dictionary, Penguin Books Ltd, London, UK.

[6] Murthy, M. (2007). LONGMAN Business English Dictionary, Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh, Harlow, UK.

[7] Law, J. (2008). Oxford Dictionary of Finance and Banking, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

[8] Harris, Ph. (2009). The Penguin Dictionary of Marketing, Penguin Books Ltd, London, UK.

[9] Pallister, J. and Isaacs, A. (2009). Oxford Dictionary of Business and Management. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

[10] Ayto, Twentieth, 410.

[11] Law, J. (2006). A Dictionary of Business and Management. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 246.

[12] BNC

[13] Ayto, 477.

[14] Ibid, 542.

[15] Ibid.

[16] BNC

[17] BNC.

[18] Murthy, LONGMAN, 48.

[19] BNC.

[20] Murthy, LONGMAN, 51.

[21] BNC.

[22] Murthy, LONGMAN, 64.

[23] BNC.

[24] Law, A Dictionary, 63.

[25] COCA = Corpus of Contemporary American English, available at: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/(Hereinafter, the spelling and punctuation of the cited source are preserved. – T.F.)

[26] Tuck, Oxford, 117.

[27] COCA.

[28] Law, A Dictionary, 147.

[29] COCA.

[30] Butler, B. A Dictionary of Finance and Banking, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 105.

[31] BNC.

[32] Murthy, LONGMAN, 561.

[33] COCA.

[34] Murthy, LONGMAN, 337.

[35] COCA.

[36] Law, A Dictionary, 13.

[37] BNC.

[38] Harris, Ph. The Penguin Dictionary of Marketing. Penguin Books, London, UK, 82.

[39] COCA.

[40] Law, A Dictionary, 437.

[41] BNC.

[42] Murthy, LONGMAN, 16.

[43] Ibid, 240-241.

[44] Tuck, A. Oxford Dictionary of Business English. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 425.

[45] Tuck, Oxford, 128.

[46] Law, A Dictionary, 490.

[47] COCA.

[48] COCA.

[49] Bannock, Gr. The New Penguin Business Dictionary. Penguin Books, London, UK, 342.

[50] Tuck, Oxford, 446.

[51] Murthy, LONGMAN, 160.

[52] Butler, A Dictionary of Finance and Banking, 159.

[53] Murthy, 78.

[54] COCA.

[55] BNC.

[56] Murthy, LONGMAN, 135.

[57] BNC.

[58] Murthy, LONGMAN, 441.

[59] BNC.

[60] Ayto, 564.

[61] BNC.

[62] Murthy, LONGMAN, 193.

[63] BNC.

[64] Murthy, LONGMAN, 16.

[65] BNC.

[66] Harris, The Penguin, 69.

[67] COCA.

[68] Fedorov, B. G. (2004). Novyj anglo-russkij bankovskij i ekonomicheskij slovar’ [English-Russian banking and economic dictionary], Limbus Press, Sankt-Peterburg, Russia. (In Russian); Eskin, L. N, Fedina, A. M., Butnik, V. V., Fagradyanc, I. V. (2007). Sovremennyj anglo-russkij slovar’ po ekonomike, finansam i biznesu [Contemporary English-Russian Dictionary on Economics, Finance & Business], Veche, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian); Terekhov, D. Yu. (2001). Anglo-russkij slovar’ po buhgalterskomu uchetu, auditu i finansam [English-Russian Dictionary on Accounting, Auditing and Finance], Askeri, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian); Timoshina, A. A. (2009). Russko-anglijskij slovar’ po ekonomike [English-Russian Dictionary on Economics], MGU, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Reference lists

Autelli, E. (2021). The origins of the term “phraseology”, Yearbook of Phraseology, 12, 7‒32. (In English)

Ayto, J. (1999). Introduction, Twentieth Century Words. The Story of the New Words in English over the Last Hundred Years, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 3‒10. (In English)

Arakin, V. D. ([1979]2005). Sravnitel’naya tipologiya angliyskogo i russkogo yazykov [Comparative typology of English and Russian], FIZMATLIT, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Blake, N. F. (2005). A History of the English language, MacMillan Press Ltd, London, UK. (In English)

Cartwright, R. I. (2005). Key concepts in information and communication technology, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, UK. (In English)

Cowie, A. P. (1998). Phraseology: Theory, Analysis and Application, Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Cowie, A. P., Mackin, R. and McCaig, I. R. (2000). General Introduction, Oxford Dictionary of Current Idiomatic English. Vol. 2: Phrase, Clause and Sentence Idioms, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 10‒17. (In English)

Cserép, A. (2008). Idioms and Metaphors, in Andor, J., Hollósy, B., Laczkó, T. and Pelyvás, P. (eds.), When Grammar Minds Language and Literature, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, 85‒94. (In English)

Erman, B. (2007). Cognitive processes as evidence of the idiom principle, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 12 (1), 25-53. (In English)

Fedulenkova, T. (2015). Terms of Phraseological Character in Specific Domains, Proceedings of the annual International conference “LSP Teaching and Specialized Translation Skills Training in Higher Education Institutions (LSP & STST)”, Moscow, Russia, 181‒184. (In English)

Fedulenkova, T. (2016). Isomorphic models in somatic phraseology based on synecdoche in English, German and Swedish, Language and Culture, 2 (34), 6‒14. (In English)

Fedulenkova, T. (2019a). Pragmatic functions of modern English phraseology, Research Result. Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 5 (2), 74‒83. DOI: 10.18413/2313-8912-2019-5-2-0-8. (In English)

Fedulenkova, T. (2019b). Isomorphism and allomorphism of English, German and Swedish phraseological units based on metaphor, Studia Germanica, Romanica et Comparatistica, vol. 15, 3 (45), 126‒134. (In English)

Fedulenkova, T. N. (2021a). Substantive phraseological terms of a two-component structure, Research Result. Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 7 (2), 114‒127. DOI: 10.18413/2313-8912-2021-7-2-0-11. (In English)

Fedulenkova, T. (2021b). Teaching Types of Semantic Transference in Business English Terms, 15th ESSE Conference Programme and Book of Abstracts, Universitè de Lyon, Lyon, France, 100‒101. (In English)

Fennel, D. (2004). A History of English: a sociolinguistic approach, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Fernando, Ch. (1996). Idioms and Idiomaticity, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Khamkhien, A. and Wharton, S. (2020). Constructing subject-specific lists of multiword combinations for EAP: A case study, Yearbook of Phraseology, 11, 9‒34. (In English)

Kunin, A. V. (1996). Kurs frazeologii sovremennogo angliyskogo yazyka [A course of phraseology of modern English], Vysshaya Shkola, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Leichik, V. M. (2009). Terminovedenie: Predmet, metody, struktura [Terminology Studies: Subject, methods, structure], Knizhnyi dom «LIBROKOM», Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors We Live By, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA. (In English)

Moon, R. (1998). Fixed Expressions and Idioms in English: A Corpus-Based Approach, Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Murthy, M. (2007). Explanatory notes, LONGMAN Business English Dictionary, Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh, Harlow, UK, 6‒9. (In English)

Naciscione, A. (2010). Stylistic Use of Phraseological Units in Discourse, John Benjamin Publishing Company, Amsterdam / Philadelphia, Netherlands / USA. (In English)

Pashchenko, N. M. (2018). Osobennosti ispol’zovaniya biznes-idiom v anglijskom yazyke [Peculiarities of using business idioms in English], Filologicheskienauki. Voprosyteoriiipraktiki [Philological Sciences. Questions of theory and practice], 11 (89), ch. 1, 150‒155. (In English)

Peters, E. and Pauwels, P. (2015). Learning academic formulaic sequences, Journal of English for academic purposes, 20, 28‒39. (In English)

Ponomarenko, V. A. (2007). Frazeologicheskie edinicy v delovom diskurse (na materiale anglijskogo i russkogo yazykov) [Phraseological units in business discourse (on the material of English and Russian languages)], Ph.D. Thesis, SFU, Krasnodar, Russia. (In Russian)

Simpson-Vlach, R. and Ellis, N. C. (2010). An academic formula list: New methods in phraseology research, Applied Linguistics, 31 (4), 487‒512. (In English)

Siyanova-Chanturina, A. (2015). On the ‘holistic’ nature of formulaic language, Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 11 (2), 285‒311. (In English)

Schmitt, N. (2004). Formulaic sequences: Acquisition, processing and use, John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (In English)

Stockwell, R. and Minkova, D. (2002). English Words: History and Structure, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Stubbs, M. (2007). An example of frequent English Phraseology: Distributions, structures and functions, Corpus Linguistics 25 years on, 89‒105. (In English)

Tangpijaikul, M. (2014). Preparing business vocabulary for the ESP classroom, RELC Journal, 45 (1), 51‒65. (In English)

Tuck, A. (2000). Preface, Oxford Dictionary of Business English (for learners of English), Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 3‒4. (In English)

Wood, D. (2015). Fundamentals of formulaic language, Bloomsbury Academic, London, UK. (In English)

Ziem, A. and Flick, J. (2018). A Frame Net Construction Approach to Constructional Idioms, Modern Phraseology Issues, SAFU, Arkhangelsk, Russia, 142‒161. (In English)