Euphemism as a linguistic strategy of evasion in political media discourse

Abstract

The article describes the structural, semantic and pragmatic features of political euphemisms, which are used as a means of implementing the strategy of evasion of truth in modern English-language political media discourse. A corpus of modern English political euphemisms is explored from the perspective of the general scientific approach of “a man in a language”, which makes the study relevant and original. The study examined the language material collected from the British and American media publications of 2020-2021. The analysis was based on the application of the componential, distributive, and contextual methods, as well as the quantitative research methods, contributing to a deeper understanding of the structure, semantics, and pragmatic nature of political euphemisms in modern English. Four major categories of political euphemisms identified in the articles on social and political topics are 1) economic euphemisms; 2) politically correct euphemisms; 3) military euphemisms; 4) diplomatic euphemisms. The article presents the quantitative data on the structural patterns, euphemism strategies and devices, and the quantitative ratio of the items representing the initial and resulting euphemistic nominations. The findings suggest that the political media discourse is influenced by considerations of political benefits, which often prescribe concealing the truth. The use of euphemistic substitutes in the media is strategically motivated, so political euphemism can be seen as a discursive tactic of truth evasion.

Introduction

Currently, the problem of (un)truthfulness in political media discourse is extensively discussed in linguistics. The political discourse is primarily aimed at convincing the targeted reader and inducing action. This aim is realized through manipulative strategies, tactics and techniques (Zhikhareva, 2021: 33). The strategies utilized by modern media aim at distorting information, substituting notions and concepts, and hiding unappealing facts. Euphemism is one of the strategies used in the media, characterized by variability and dynamism, serving as a means of public opinion formation and reflecting changes in public life (Shubina and Sedova, 2021). Political euphemisms make it possible to veil the negative reality and the consequences of adverse political actions, thus, making the desired impact on mass audience implicitly. Within this study, political euphemism is defined as a tool for implementing the strategy of truth evasion.

The functioning of political euphemisms in modern English-language media is of particular concern, taking into consideration the fact that modern linguistics is interested in identifying how the language reflects the real world and relations between different phenomena. Modern linguistics is often characterized as anthropological because the study of linguistic processes involves the human factor, implying that the text creator and the recipient of information are involved and included in the description of linguistic mechanisms.

The study of political euphemism has received substantial critical attention in such fields of science as political linguistics, communicative and cognitive linguistics, semantics, stylistics, sociolinguistics, textlinguistics, rhetoric, and psycholinguistics. Recently, considerable literature has grown up around the theme of political euphemisms as a lexical phenomenon; however, linguistic studies lack a comprehensive analysis of the structural, semantic, and pragmalinguistic characteristics of the euphemistic substitutes in the political sphere. Specifically, there has been no detailed investigation into euphemisms used as a discourse tool of implementing the strategy of truth evasion in modern English-language media, and establishing relations between the structure, semantics, and pragmatics of political euphemisms, which constitutes the novelty of the present research. A clearer understanding of political euphemisms functioning in the English-language media would make it possible to more accurately identify the hidden goals and motives of the authors (which may be to manipulate the reader, avoid offending certain groups of people, and/or break social conventions, soften or neutralize an unpleasant message) and to determine which social factors determine the choice of euphemistic substitutions.

This paper describes the dynamics of the functioning of political euphemisms in contemporary English. It focuses on existing research data and new language material extracted from the present-day English-language media. The following aspects are analyzed: 1) thematic fields; 2) structural patterns of political euphemisms in the English-media publications; 3) the most frequent strategies for creating the lexical items in question; 4) pragmalinguistic characteristics of political euphemisms and their functioning in the socio-political media to implement the strategy of truth evasion. This study applies the componential, distributive, and contextual methods, as well as the pragmatic and quantitative approaches. The corpus of 482 political euphemisms represents the data of the study collected through the continuous sampling method from the news online publications of 2020-2021 on social and political issues. The sources of the data are the news websites: BBC News, The Guardian, Euronews, SkyNews, The New Yorker, The Week, The National Interest, ABC News, The New York Times. These Internet media sources report on a wide array of political and social events worldwide, providing abundant reference material.

Literature review

A large and growing body of literature has investigated political euphemisms in recent years. Many linguists (Toroptseva, 2003; Sheigal, 2004; Ivanova, 2004, Mironina, 2012; Chovanec, 2019; Hong, 2019; Khidesheli, 2020; Varshamova et al., 2020) identify political euphemisms as a separate class of euphemisms. Obvintseva (2004), Ham (2005), Boyko (2005), Potapova (2008), Burridge (2012), Li-na (2015), Gritsenko (2018), Majeed and Mohammed (2018), Felt and Riloff (2020), Jing-Schmidt (2022) describe the functions and strategies of euphemization in different texts. The manipulative potential of euphemistic renaming in the media language is reviewed by Kiprskaya (2005), Baskova (2006), Pryadilnikova (2009), Morozov (2015), and others.

This study defines political euphemisms as a tool for implementing the linguistic strategy of truth evasion. Evasion of truth in media discourse is a consequence of a biased representation of reality, which is usually associated with intended information handling. Intended transformation of information is considered the most important component of manipulative influence (Dotsenko, 1997).

In the present-day political media discourse, euphemization represents a tool for focus manipulation, which implies shifting the pragmatic focus of attention (a frame of reference about the denotatum). It changes the perspective and, accordingly, the nature of perception of the denotatum, which makes the recipient perceive it in a more favorable light (Sheigal, 2004: 173). Focus manipulation mainly belongs to the zone of partial distortion. According to Sheigal, distortion of information about the denotatum can be represented as two gradation scales of the information space: 1) reporting a fact – understating (partial distortion of information) – complete silence (concealing information); 2) truth (full compliance with the facts) – partial distortion of information – outright lie (absolute distortion of information). The phenomenon of juggling facts belongs to the zone of partial distortion, which includes various types of a referential shift related to euphemization (Sheigal, 2004: 174).

Euphemisms conceal the genuine nature of the phenomenon by creating a neutral or positive connotation through the associative substitution mechanism and the so-called ‘buffer’ mechanism. Concealing facts is a more effective way of transmitting information compared with a direct impact on a person. The manipulative effect of euphemism lies in the associative substitution mechanism, thanks to which the speaker has a kind of defense, distracting the recipient’s attention from a taboo concept, implying, at least formally, other contents (Vidlak, 1967: 276-277).

Moskvin defines the political euphemisms as masking euphemisms, the distinguishing features of which are: 1) appealing to a broad audience; 2) being initiated by the political power, i.e., ideology influence on the public opinion; 3) indirect or secondary naming of anything in political communication (leading to the audience’s negative attitude) to either deceive the audience or represent an unsettling concept / reality in a less embarrassing way (Moskvin, 2017: 117).

Lawrence believes that euphemism has been a faithful ally of military and political intrigue for centuries. It is its inherent nature, which is evident in the following examples of political euphemisms: liquidation instead of killing; separate development instead of racial apartheid (Lawrence, 1973: 75). He also points to the similarity of political euphemisms with the so-called “newspeak” or “doublespeak” language. This term was first used in George Orwell’s novel “1984” (1948) (Orwell, 1968, 1978). Doublespeak includes words specially created for political purposes, words that carry a political message and specifically intended to exert the desired influence on their user (Obvintseva, 2004: 50). Lutz identifies four categories of doublespeak; one of them is euphemism. He distinguishes between euphemisms proper and doublespeak: when euphemism is used to mislead or deceive, it becomes doublespeak (Lutz, 1989: 1-3).

Within the framework of this study, the term “political euphemism” identifies a type of euphemisms used in political discourse to substitute words or expressions considered political taboos characteristic of particular societies and times. It is a multifunctional phenomenon as it serves the purposes of mitigating the seriousness of the message and veiling the ideas rendered by language expression (Mironina, 2012: 4). Choosing a euphemism instead of naming the object directly, the communicant implies a negative attitude to the phenomenon, or the inappropriateness of the situation for its direct name, while the stigmatization of the denotatum itself does not change (Bushuyeva, 2021: 47). In other words, stigmatization of the denotatum correlates with the existing ideology and society values.

The modern political media discourse euphemizes concepts of reality in various spheres, for example, the English language demonstrates a more active use of military euphemisms, which hide the truth and calm the imagination (Howard, 2003). War is a horrifying event associated with grief, blood, and death; therefore, it causes negative feelings and emotions that are fixed in the linguistic worldview of society. The following expressions can be classified as military euphemisms: the Vietnam efforts; push-button war; peacekeeping mission (Moskvin, 2017: 132).

The so-called diplomatic euphemisms also belong to political euphemisms. For example, Larin considers euphemism to be an essential communication component in diplomacy (Larin, 1961: 101). The following expressions have a clear euphemistic nature: differences among friends (about the meeting of the Presidents of Russia and the United States); considerableprogress was made (about a fruitless summit) and some others (Grimaldi, 2003: 55). Spy euphemisms are also part of the diplomatic group: agent – spy, earpiece – informant, electronic surveillance – illegal wiretapping.

Another category of political euphemisms refers to the economic sphere, such as inexpensive, economically priced instead of cheap, and many more. Moskvin (2017), Potapova (2008), and others distinguish business euphemisms within the group of economic euphemisms that function in the political media discourse, for example, right-sizing, repositioning, reshaping used instead of redundancies (Moskvin, 2017: 134).

One more class of political euphemisms is politically correct euphemisms. According to Ter-Minasova (2000), “politically correct” euphemisms substitute impolite or insensitive words and word combinations which hurt people’s feelings and sense of dignity, interfere with human rights, or they are too straightforward in regard to different characteristics of an individual like age, health, gender, social disadvantages or aesthetic aspects (Ter-Minasova, 2000: 216-217). Some scientists associate political correctness with a particular social group or a political movement and infringement of minority rights. The masking substitute acquires the status of a politically correct euphemism if the initiative of a minority group and a corresponding masking nomination receives support of the authorities (sometimes warranted by law, which makes it possible to take the offender to court) (Moskvin, 2017: 136).

Wodak (1997), Baskova (2009), Sheigal (2004), Bachem (1979) identify the following features of political euphemisms: they are motivated and based on certain values; they are slogan-like; they have a dialectic nature of euphemistic transformation; they form us-versus-them opposition; they belong to the class of agonal signs and can act as a tool for implementing the truth evasion strategy. Each feature is associated with some factors responsible for the use of political euphemisms. According to Veber (2004) Tembiraeva (1991), Sheigal (2004), the factors that determine the widespread use of political euphemisms in political communication include 1) the need to comply with the society’s rules of cultural correctness; the desire of the author of the message to choose such designations that not only soften certain unacceptable words or expressions but mask or veil reality. In this case, euphemism serves as a means of avoiding “losing face” when it is necessary to publish facts that are humiliating and damage the country’s reputation (loss of allies, territorial losses, international sanctions); 2) the desire to prevent public anger, mass indignation, etc. Wodak describes euphemisms as a psychological method of neutralization of a person’s defensive response to a possible threat (Wodak, 1989: 143).

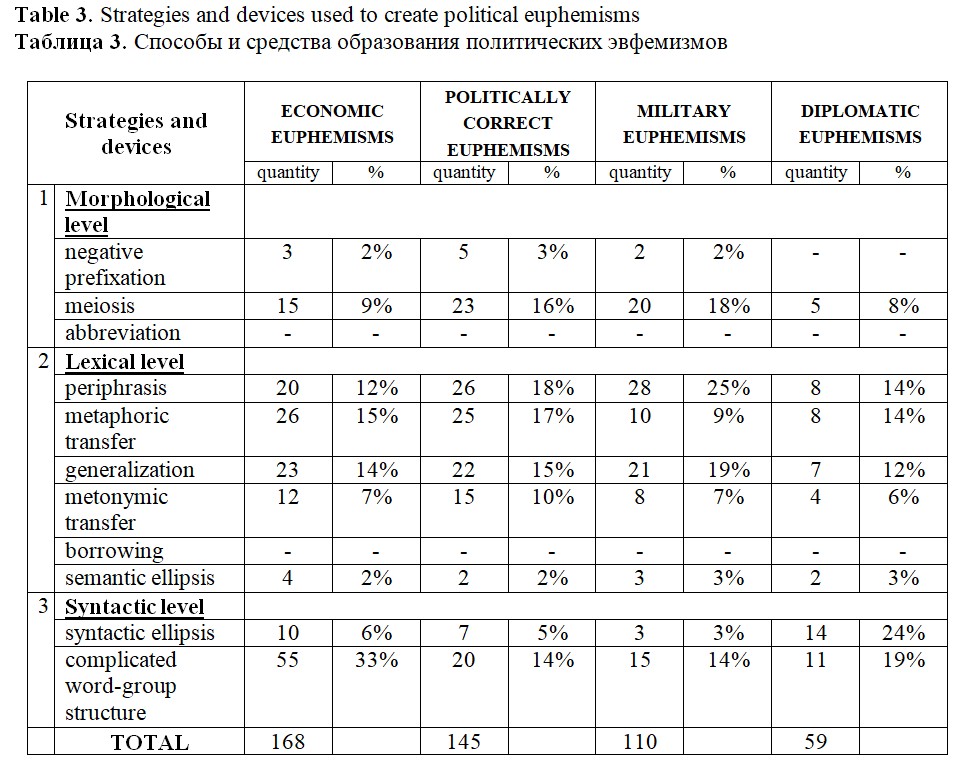

To understand the nature of euphemistic substitution in political media discourse, it is essential to identify the linguistic strategies used to create euphemisms. The literature review has shown that many linguists (Krysin, 2000; Neaman and Silver, 1995; Vidlak, 1967; Moskvin, 2017; Glios, 2007, and others) agree that euphemization in the political discourse appears at the morphological, lexical, and syntactic linguistic levels. Negative prefixation (litotes), meiosis, and abbreviation are morphological modifications occurring in political communication. Euphemistic encryption in the political media discourse is mainly implemented at the lexical level through such euphemization techniques as periphrasis, generalization, metaphoric transfer, metonymic transfer, borrowing, semantic ellipsis, acronyms and abbreviations, and vague terms. The syntactic euphemization strategies are observed in the complication of the phrase structure or as ellipsis.

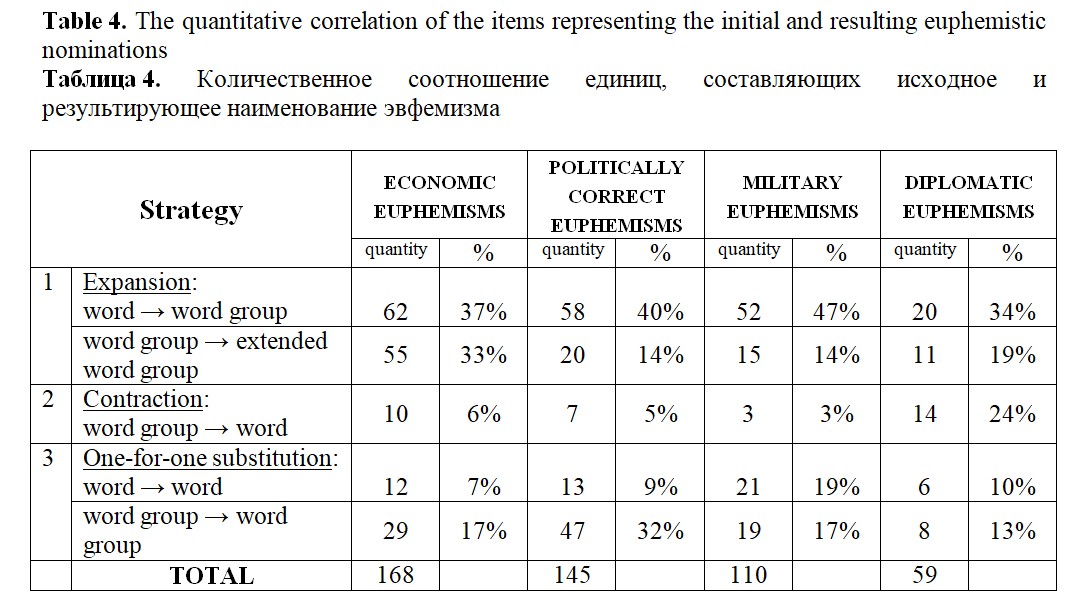

All linguistic devices that allow avoiding direct nomination in the political media discourse can be classified on 1) the basis of the quantitative ratio of the items which represent the initial and resulting nominations; 2) the nature of transformations and the resulting semantic effect.

All euphemistic substitutions fall under three categories:

- expansion: word → word-group (immigrants → people from abroad);

- contraction: word-group → word (unilateral embargo → quarantine);

- one-for-one substitution: the number of components does not change (kill → neutralize) (Sheigal, 2004: 176).

Despite a large body of literature on political euphemisms, the association between the formal and semantic components of this lexical phenomenon has not been fully explicated, particularly, when it is used as a tool for truth evasion in the present-day political media discourse. This study aims to establish tendencies in the use of political euphemisms in the English-language media, which can shed more light on the functioning of political euphemisms in the English language.

Methods and Materials

Political euphemism is a complex linguistic, social, and cognitive phenomenon; therefore, it should not be analyzed from the lexical and semantic perspective only, but also in terms of the linguocultural and functional-and-pragmatic aspects. The analysis of this linguistic phenomenon should address both linguistic and extralinguistic factors of the speech situation.

The present study investigates the political euphemism as a tool for implementing the strategy of truth evasion in modern political media discourse. It is carried out within the framework of functional pragmalinguistics, which deals with the linguistic behavior of the text creator who consciously and deliberately chooses linguistic devices to achieve a desired impact on the recipient.

Interaction of language and ideology, which manifests itself in the use of political euphemisms in reliance on their pragmatic nature, is also of interest for the research. The present study attempts to reveal the relationship between language and ideology within the cognitive-discursive paradigm adopted in political linguistics. This approach is adopted by linguistics, psycholinguistics, philosophy of language, and linguodidactics to study thinking and communication, tools / strategies for influencing the addressee in the communication process, and the role of language in intellectual creation and knowledge processing (Sahakyan, 2010: 3).

Consequently, we adopted the descriptive and cognitive approaches to characterize the pragmalinguistic nature of political euphemisms used as a tool for implementing the strategy of truth evasion. The present paper describes a formal representation of the euphemistic renaming, thesaurus, and motivation characteristics of political euphemisms.

There is no doubt that context determines the use of euphemisms in the political media discourse to a much greater extent than in other spheres of communication. Thus, Crespo-Fernández describes euphemism as a discursive and context-sensitive phenomenon; it is revealed exclusively in speech, and its quality depends on the context in which it is used (Crespo-Fernández, 2014). Therefore, when analyzing the language material, we gave close consideration to a broad context of the news message containing euphemistic substitution, the associated political situation, and the motives of the author who used the euphemism in a given context.

The language data were excerpted from 750 news Internet articles published by BBC News, The Guardian, Euronews, SkyNews, The New Yorker, The Week, The National Interest, ABC News, The New York Times in 2020-2021. The articles deal with social, economic, and political issues. We identified 482 euphemistic items used by the authors of the publications as a tool for implementing the strategy of truth evasion.

Findings and discussion

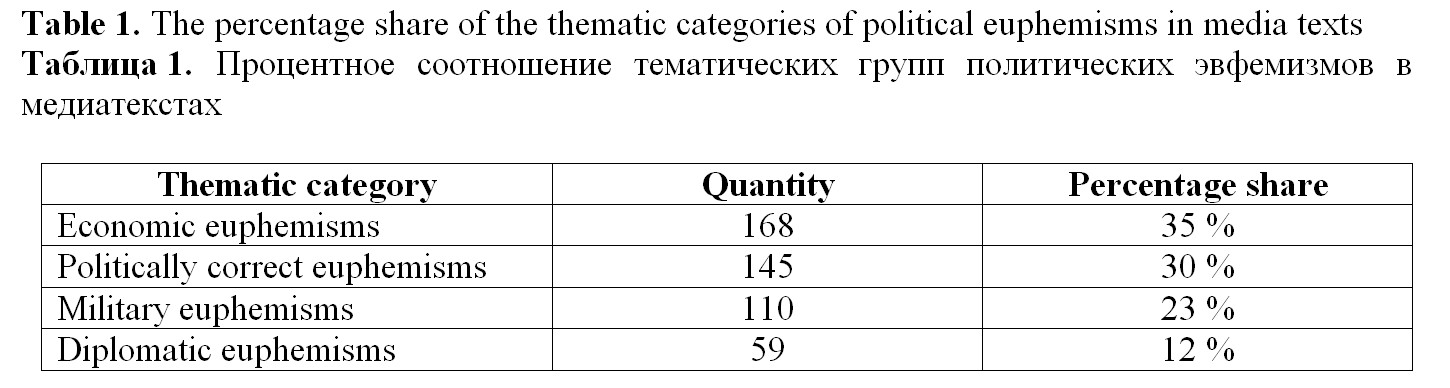

The analysis of the collected language data made it possible to identify four major categories of political euphemisms used by the authors of the articles on social and political topics: 1) economic euphemisms; 2) politically correct euphemisms; 3) military euphemisms; 4) diplomatic euphemisms.

The first category comprises euphemistic substitutions used to veil the nature of the current poor global economic conditions mainly caused by the consequences of COVID-19.

The category of politically correct euphemisms consists of words and expressions used to prevent associations with racial, ethnic, property, age, mental health, and disability discrimination. It is customary for the English-language press to avoid naming certain groups of people directly, talking about race, poverty, or disability as a distinctive feature of those included in a particular group. These euphemisms are usually meant to neutralize discrimination barriers, on the one hand, but at the same time to camouflage the extent of the problem, and minimize the negative effect of the message. More active use of euphemisms in the social sphere is also driven by recent large-scale protests aimed at combating racism and police brutality in many cities worldwide.

The third category includes euphemisms camouflaging military operations and their consequences in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Ukraine. Diplomatic euphemisms are attenuating substitutions, which are associated with the domestic and foreign policy of Germany, the USA, China, Great Britain, Russia, Spain, Italy, North Korea, Brazil, and other states.

The quantity and the percentage share of each category of the political euphemisms are presented in Table 1.

The category of economic euphemisms is dominant in the material (35%). It is most likely a result of the unstable global economic situation and the negative consequences of the global financial crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The least numerous category (12%) is diplomatic euphemisms used in articles dealing with international relations. We may suggest that the issues associated with the domestic and foreign policy were less relevant against the background of what was happening in the world over the studied period.

The analysis of the thematic category of economic euphemisms indicates that the economic crisis hurt both the economic development of particular states and the global economy. Many countries had to face a decline in exports and the rising unemployment rate. In the context of the pandemic, unemployment issues have become especially relevant, and the material demonstrates the use of various names for people who have lost their jobs: people out of work, those left in need, vulnerable citizens,furloughed workers, people put on leave.

The global economic crisis and its consequences are one of the central issues in English-language online publications which are full of indirect euphemistic substitutions for this concept, with simple word-groups (only two components) prevailing: battered economy; economic disruption; economic downturn; economic hardship; economic pain; informal economy. There are also word-groups of a more complex structure (depressing economic data; coronavirus-frozen economy; economic hibernation period; drop in economic activity).

The prefix re- in verbs forms euphemistic substitutes, contributing to softening and attenuating the nature and scope of the financial crisis (to reexamine, to re-regulate, to rebuild, to restart, to revamp, to redesign, to rework, to reinvigorate, to reinforce, etc.). However, the very fact of what happened is not veiled (the crisis certainly damaged many economic sectors), but the nomination of the crisis is euphemized. Obviously, this language item still correlates with a negative denotatum, implying that if the authorities resort to re-measures, something has gone wrong, out of control, not as planned.

The quantitative ratio of the items, which represents the initial and resulting nominations in the category of economic euphemisms, is mainly represented by the patterns: word → word-group and word-group → extended word-group. Expansion is the most common type of euphemistic substitution since a change in the formal structure leads to a semantic shift that produces a softening effect. Equivalent substitution is a non-productive way of euphemistic renaming. We suggest it is due to one of the psychological characteristics of people, according to which we tend to be hyperverbal when we want to mitigate the unpleasant. It results from dispersion of attention when perceiving wordy expressions, which helps people distract from negative denotata.

As for the nature of the semantic shift and the resulting semantic effect, most of the analyzed euphemistic items of the given group are substitutions based on decoding accompanied by a shift in the evaluative rating. Down-toning is achieved through metaphoric transfer, generalization, periphrasis, and gradation (understatement). These strategies of euphemization are productive with economic euphemisms (Table 3).

The pragmatic focus shift characteristic of the euphemistic substitutions of the given thematic category can be represented as follows: global economic problems → solution of global economic problems, although it often means escaping problems through partial coverage of the problem. It may be explained by the desire to hide the acuteness of social problems associated with the economic crisis consequences, downplaying their significance, thereby relieving social tension and avoiding social conflict. The dominant values are as follows: the country should stay strong; there should be no unemployed people in society; taxes should not be excessive.

It is necessary to highlight that most economic euphemisms are of descriptive and contextual nature. Interestingly, the economic euphemisms used by the authors of media texts are generally accepted and well-known. Nevertheless, they are effective at veiling and camouflaging the problems in the country’s economy.

The use of politically correct euphemisms in the texts of modern English-language media aims to mask the problems of social injustice through verbal camouflage. It indicates the timeless nature of the phenomenon of political correctness and its current relevance.

Recently, European societies have had to deal with a severe refugee and migration crisis. The governments have adopted policies that would allow them to host refugees, but the populations of these countries do not always approve of these policies. Refugees have a negative image in society; they are usually seen as poorly-educated and bad-mannered people prone to crime. In this case, the function of manipulation means to generate a more favorable attitude to refugees, improving their public image. The politically-correct euphemisms like asylum seekers, boat people, undocumented immigrants appeal to the readers’ compassion. The authors of articles on this topic try to convince the reader that refugees are people who are experiencing a difficult life situation and need help. The euphemism in this case is a way of “saving face” of a political entity of a lower status. Euphemistic renaming results in shifting the pragmatic focus.

After the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, numerous publications were devoted to racial discrimination in the United States and other countries. It resulted in the active use of euphemisms denoting a group of people according to their race identification, with the euphemism African Americans used most frequently. We also recorded the use of the euphemisms Native Americans,the communities of colour, and people of colour, which had been popularized by the civil rights activists. Some of such euphemisms are meant not only to eliminate the discrimination context, but also foster self-respect and highlight the uniqueness: We take very seriously any allegation that a curacy post, or any other position, may have been denied tosomeone on the grounds of their ethnic heritage (BBC 2020).

Taken as a whole, the euphemisms of this thematic category comply with the requirements of political correctness and mainly serve to hide or downplay social problems, avoid social conflict, and prevent an individual of a lower social status from “losing face”.

The pragmatic focus shift, characteristic of the politically correct euphemisms, can be represented as follows: unequal status → equal status, intentional violation of social norms → accidental violation of social norms. These patterns allow us to deduce the values implied in most politically correct euphemisms: all citizens are equal; everyone has the same/equal social rights; society should not have too poor and too rich citizens; everyone should have decent living conditions.

The range of strategies to euphemize the lexical items of the given thematic group is quite diverse. From the formal point of view, politically correct euphemistic substitutions are represented by the patterns word → word-group and word-group → word-group, which suggests that, in some cases, the authors of the Internet publications try to avoid confrontation with an unsettling topic which needs veiling, and they do so through verbosity. In other cases, they hide the truth about a stigmatic denotatum with the help of an equivalent nomination, which is more powerful, however. Talking about the linguistic devices, the most frequent are substitutions that partly increase semantic ambiguity or lead to an increase in referential ambiguity (periphrasis, metaphoric transfer, gradation, generalization, the use of a hyperonym, extended word-groups) (Table 3).

Military euphemisms are used by and about the military to blur distinctions between war and peace, violence and humanity; they are new evasive expressions that mask or alleviate the violent and unpleasant nature of their referents (Kiš, 2014). As war is seen as a political and diplomatic blunder provoking a strong public reaction, the political media discourse euphemizes almost any kind of military action, also renaming conflict parties, military personnel, terrorist groups, and hostile forces (Mironina, 2014: 100).

Many of the media texts that served as data sources for this study are devoted to the tensions between Russia and Ukraine and describe the desire of Western countries to prevent Russia from military action: The European Council reiterates its support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. “Any further military aggression against Ukraine will have massive consequences and severe cost in response,” the statement read (Euronews 2021). The semantic ambiguity of euphemistic substitutions in such contexts leads to an increased ambiguity of the whole message. The euphemistic effect is achieved through the technique of diffusion of the semantic content (generalization).

The authors of the articles deliberately resort to the words of broad semantics like effort, mission, action, operation, casualties to designate military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Ukraine. This technique relies on a combination of psychological and ideological influences, which contributes to hiding the truth and favouring “half-truth”. Euphemization acts as a manipulative tool and is conditioned by manipulative goals; it is an attempt to implicitly create a required emotional and evaluative attitude towards the represented event. The words of broad semantics contribute to the transmission of incomplete or distorted information by focusing on minor details and relegating the main idea to the background.

The main functions of the military euphemisms in political media discourse are veiling and camouflaging reality. The motives for creating and using euphemisms in news reports on hostilities and armed conflicts are most often the desire to veil the situation, conceal the true nature of a concept, and disguise illegal or immoral activities, thereby avoiding a strong negative response from the public. The analysis of the euphemistic items indicates that the theme of war needs verbal camouflage to ascribe legitimacy to the actions of politicians and the military.

The quantitative correlation of the items, which represents the initial and resulting nominations in the category of military euphemisms, are mainly represented by the pattern word → word-group (Table 4). As for the nature of transformations, military euphemisms are most frequently formed by means of periphrasis and generalization (Table 3).

The pragmatic focus shift characteristic of the military euphemism renaming can be represented by the following patterns: immoral action → noble motive; forced choice → free choice; violence → normal course of events; we are responsible → they are responsible.

The analysis of the military euphemisms makes it possible to describe the value dominants which they reveal. These are: war is evil; no one has the right to dispose of the life of another person.

The thematic group of euphemistic diplomatic substitutes includes euphemisms that veil the nature and consequences of the domestic and foreign policy of the United States, Germany, Spain, Italy, China, Great Britain, Australia, and other countries.

As mentioned above, many world economies, including the EU countries, suffered seriously under quarantine restrictions. To combat the economic crisis threatening many countries, the EU decided to allocate the budget money to support other countries. However, EU member countries were not in a similar financial position. Some countries had been in economic trouble and debt even before the coronavirus outbreak. So, the EU countries with a more developed economy disapproved of this decision. The Internet publications reflect this problem. For instance, a diplomatic euphemism frugal state is often found in publications: Several “frugal” states object to taking on debt for other countries (BBC News 2020).

Another interesting example of a diplomatic euphemism that implements the strategy of evading the truth is the euphemistic renaming fragile state, which refers to a country with an unstable political system and a weak economy, undergoing military, ethnic, or religious conflicts and their consequences, the rights of whose citizens are constantly violated. In this case, the semantic content is blurred, which is achieved through euphemism. This nomination shifts the perception of reality in a way favourable for the addresser and creates a vague, ambiguous idea of the state of affairs, which the recipient can only guess about.

Taken as a whole, the most frequent and productive occurrences in this category are extended word-groups formed by means of expansion (Table 4). The most frequent euphemization techniques in the category are metaphoric transfer, periphrasis, and generalization (Table 3).

The pragmatic focus shift characteristic of the category of the diplomatic euphemisms can be represented by the following patterns: immoral action → noble goal; adverse consequences → valid reason; global nature of the problem → specific case.

The main motive of journalists, who create and use euphemisms in the field of diplomacy, is to observe diplomatic etiquette. The use of diplomatic euphemisms in present-day English-language media can also be explained by the desire to camouflage unlawful and immoral actions, downplay social problems, avoid “losing face”, and “save face” of a political entity. The diplomatic euphemisms reflect the following values: the country should be respected internationally; the country must be strong; the leader should be a decent and honest person; terrorism is a threat to the state’s security.

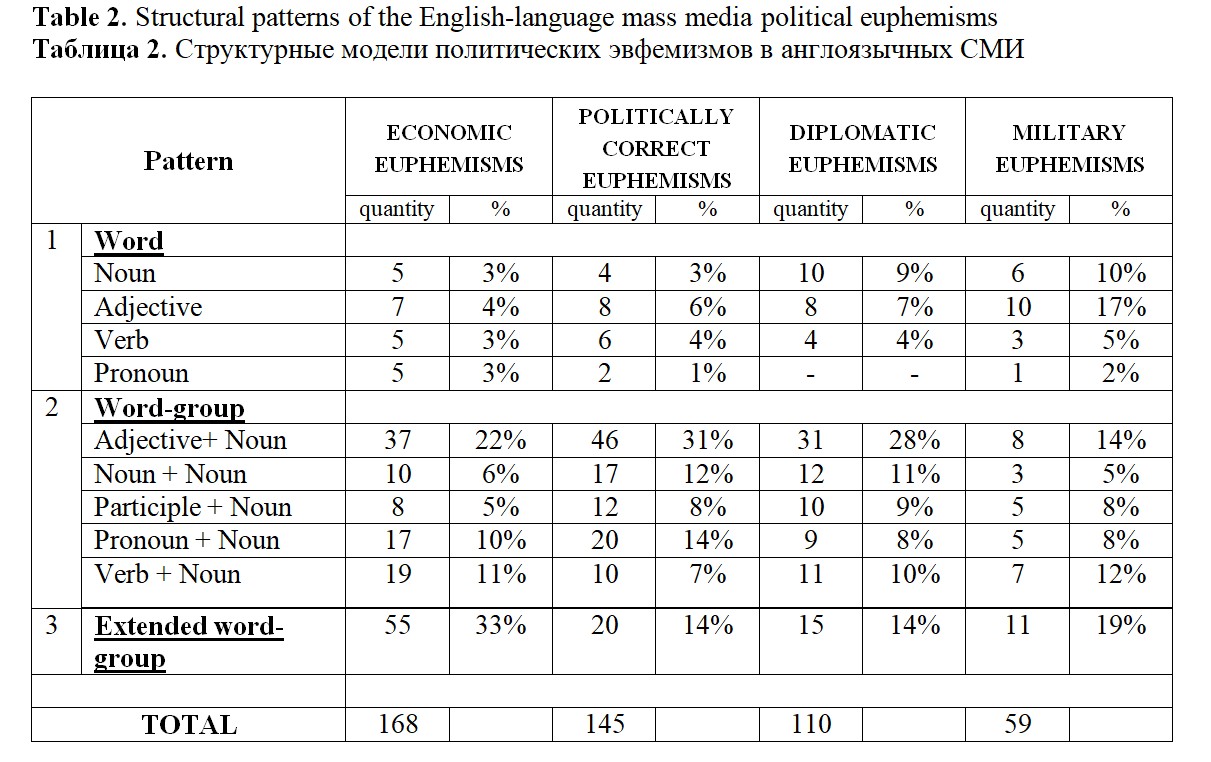

The quantitative data on the structural patterns, euphemism creation strategies and devices, and the quantitative ratio of the items representing the initial and resulting euphemistic nominations are represented in the tables below.

The findings confirm the interrelationship between the semantic features of political euphemisms and their pragmatic application in speech, i.e., the pragmalinguistic nature of political euphemism. The process of euphemistic renaming in the political media discourse is characterized by a simultaneous reflection of the nature of the referent and the speaker’s interests. It should be highlighted that political euphemisms functioning in the contemporary English-language political media discourse have strong pragmatic potential. Euphemism facilitates concealing, smoothing, or veiling the negative reality and allows presenting political events and their consequences in a favourable light due to a shift in the pragmatic focus, which leads to improvement in the stigma-related notions.

Conclusion

The comprehensive analysis of the functioning of political euphemisms and our findings suggest that sincerity in political media discourse has given way to considerations of political benefits, which prescribe concealing the truth in favour of “half-truth”. Political euphemism can be seen as a discursive tactic of truth evasion as the use of euphemistic substitutes in the media is always strategically motivated. Political euphemism as a tool for implementing the strategy of truth evasion is extensively used in the English-language media texts, serving to camouflage critical situations and disguise the state of affairs in the socio-political life of society. Euphemism represents modified information in order to achieve a particular perlocutionary effect.

Political euphemism highlights areas of social tension, characterizing social, cultural, and economic conditions. Ideas and notions about problems, events, phenomena of reality, and the world picture as a whole are constructed and translated through the prism of political euphemism. Thus, it provides the basis for identifying the dominant values.

The linguistic data of today’s English language indicate a clear growing trend towards implementing the strategy of evasion in the modern English-language media. Political euphemism, mainly functioning at the lexico-semantic level, has specific pragmalinguistic potential. It helps to conceal what is ugly, indecent, or secret, creating vagueness and sense of distance. Political euphemism is one of the most effective tools for manipulating public consciousness as it serves to change a set of ideas of the addressee about events and reality. The study of political euphemisms in the pragmalinguistic perspective opens up prospects for further research into the structure and functioning of the English-language political media discourse.

Reference lists

Bachem, R. (1979). Einführung in die Analyse politischer Texte, Oldenbourg, München, Germany. (In German)

Baskova, Yu. S. (2006). Euphemisms as a means of manipulation in the media language (based on the material of the Russian and English languages), Ph.D. Thesis, Language Theory, Kuban State University, Krasnodar, Russia. (In Russian)

Baskova, Yu. S. (2009). Manipulyatsiya na yazyke SMI: evfemizmy kak “slova-prikrytiya” [Manipulation in the Mass Media Language: Euphemisms as “Cover Words”], KSEI, Krasnodar, Russia. (In Russian)

Boyko, T. V. (2005). Euphemia and dysphemia in the newspaper text, Ph.D. Thesis, Germanic Languages, Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia, St. Petersburg, Russia. (In Russian)

Burridge, K. (2012) Euphemism and Language Change: The Sixth and Seventh Ages, Lexis [Online], 7. https://doi.org/10.4000/lexis.355(In English)

Bushuyeva, L. A. (2021) Frame of Act of “Infidelity in Love” and its Euphemistic Representations in Russian and English Linguocultures, Nauchnyi dialog, 1 (7), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.24224/2227-1295-2021-7-45-59(In Russian)

Chovanec, J. (2019). Euphemisms and non-proximal manipulation of discourse space: the case of blue-on-blue, Lingua, 225, 50-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.04.001(In English)

Crespo-Fernández, E. (2014). Euphemism and political discourse in the British regional press, Brno Studies in English, 40 (1), 5-26. (In English)

Dotsenko, E. L. (1997). Psikhologiya manipulyatsiy: fenomeny, mekhanizmy i zashchita [Psychology of Manipulation: Phenomena, Mechanisms and Protection], CheRo, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Felt, C. and Riloff, E. (2020). Recognizing euphemisms and dysphemisms using sentiment analysis, Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Figurative Language Processing, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P17 (In English)

Glios, E. S. (2007). Linguocultural specifics of the formation and functioning of euphemisms in modern English (based on the material of English-language Internet sites), Ph.D. Thesis, Germanic Languages, Belgorod State University, Belgorod, Russia. (In Russian)

Grimaldi, E. (2003). Great Progress Was Made, The Public Manager, 32 (2), 55. (In English)

Ham, K. (2005). The Linguistics of Euphemism: A Diachronic Study of Euphemism Formation, Journal of Language and Linguistics, 4 (2), 227-263. (In English)

Hong, X. (2019) A Pragmatic Study of Euphemism in English Political News, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019), 1184-1190. https://doi.org/10.2991/iccessh-19.2019.263(In English)

Ivanova, O. F. (2004). Euphemistic vocabulary of the English language as a reflection of the cultural values of the English-speaking world, Ph.D. Thesis, Germanic Languages, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Jing-Schmidt, Z. (2022). Euphemism, Handbookof Pragmatics, 24, 124-144. https://doi.org/10.1075/hop.24.eup1(In English)

Khidesheli, N. P. (2020). Euphemisms in the military text. Difficulties of translation, Materials of the conference “Humanitarian foundations of engineering education: methodological aspects in teaching speech disciplines and problems of speech training in higher education”, 1, 109-115. (In Russian)

Kiprskaya, E. V. (2005). Political euphemisms as a means of camouflaging reality in media, Ph.D. Thesis, Language Theory, Vyatka State Humanitarian University, Kirov, Russia. (In Russian)

Kiš, M. (2014). Euphemisms and military terminology, Hieronymus, 1, 123-137. (In English)

Larin, B. A. (1961). Ob evfemizmakh [About euphemisms], Scientific Notes of the Leningrad State University (Philological Sciences Series), 301 (60), 110-124. (In Russian)

Lawrence, J. (1973). Unmentionables and Other Euphemisms, Gentry Books, London, UK. (In English)

Li-na, Z. (2015). Euphemism in modern American English, Sino-US English Teaching, 12 (4), 265-270. https://doi.org/10.17265/1539-8072/2015.04.004(In English)

Lutz, W. (1989). Doublespeak:From “Revenue Enhancement” to “Terminal living”: How Government, Business, Advertisers and others Use language to Deceive you, Harper & Row, New York, USA. (In English)

Majeed, S. H. and Mohammed, F. O. (2018) A Content Analysis of Euphemistic Functions In Evro Bahdini Daily Newspaper, IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 23 (2), 87-99. DOI: 10.9790/0837-2302128799 (In English)

Mironina, A. Yu. (2012). Political euphemisms as a means of implementing the strategy of truth evasion in modern political discourse (based on B. Obama’s public speeches), Abstract of Ph.D. dissertation, Germanic Languages, Nizhny Novgorod Dobrolyubov State Linguistic University, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia. (In Russian)

Mironina, A. Yu. (2014). War as an object of euphemization in political discourse, Bulletin of VSU, 8, 99-105. (In Russian)

Morozov, M. A. (2015). Politicheskie evfemizmy kak sredstvo manipulirovania v sovremennoy publitsistike [Political euphemisms as a means of manipulation in modern journalism], The world of the Russian word, 1, 24-29. (In Russian)

Moskvin, V. P. (2017). Evfemizmy v leksicheskoy sisteme sovremennogo russkogo yazyka [Euphemisms in the Vocabulary of the Modern Russian Language], Stereotip, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Neaman, J. S. and Silver, C. G. (1995). The Wordsworth Book of Euphemisms, Wordsworth Editions Ltd, London, UK. (In English)

Obvintseva, O. V. (2004). Euphemism in political communication: Russian compared to English, Ph.D. Thesis, Ural State Pedagogical University, Comparative Linguistics, Yekaterinburg, Russia. (In Russian)

Orwell, G. (1968). Politics and the English language, in Orwell, S. and Angos, I. (eds.), The collected essays, journalism and letters of George Orwell, Mariner Books, New York, USA, 127-140. (In English)

Orwell, G. (1978) Political Euphemism in Escholz, P., Rosa, A. and Clark, V. (eds.), Language Awareness, St. Martin’s Press Inc., New York, USA. (In English)

Potapova, N. M. (2008). Euphemisms in language and speech: based on the English-language business discourse, Ph.D. Thesis, Germanic Languages, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Pryadilnikova, N. V. (2009). Evfemizmy v sovremennoy rechi [Euphemisms in Modern Speech], Izdatelstvo SGAU, Samara, Russia. (In Russian)

Sahakyan, L. N. (2010). Euphemia as a pragmalinguistic category in the discursive practice of indirect speech persuasion, Ph.D. Thesis, Russian Language, Pushkin State Russian Language Institute, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Sheigal, E. I. (2004). Semiotika politicheskogo diskursa [Semiotics of Political Discourse], Gnozis, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Shubina, E. L. and Sedova, A. V. (2021). Hedge euphemisms as tools of economic discourse, Nauchnyi dialog, 11, 183-200. https://doi.org/10.24224/2227-1295-2021-11-183-200(In Russian)

Tembiraeva, E. K. (1991). Evfemizmy na yazyke politiki i khudozhestvennoy literatury [Euphemisms in the language of politics and fiction], Word in the dictionary and text, 13-21. (In Russian)

Ter-Minasova, S. G. (2000). Yazyk i mezhkulturnaya kommunikatsia [Language and Intercultural Communication], Slovo, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Toroptseva, E. N. (2003). Euphemistic names in the aspects of language, history, culture, Ph.D. Thesis, Language Theory, Moscow Region State University, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Varshamova, P. L., Danilov, N. K. and Yashina, Y. V. (2020). The English language military euphemisms, The language of science and professional communication, 1 (2), 73-84. (In Russian)

Veber, E. A. (2004). The linguistic research of cognitive dissonance in the English diplomatic discourse, Ph.D. Thesis, Germanic Languages,

Irkutsk State Linguistic University, Irkutsk, Russia. (In Russian)

Vidlak, S. (1967). The problem of euphemism against the background of the theory of the language field, Etymology, 267-285. (In English)

Wodak, R. (1989). Language, Power and Ideology: Studies in Political Discourse, J. Benjamins, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (In English)

Wodak, R. (1997). Yazyk. Diskurs. Politika [Language. Discourse. Policy], Peremena, Volgograd, Russia. (In Russian)

Zhikhareva, N. A. and Yakovleva, E. P. (2021). Stereotypes as means of influencing mass consciousness in political discourse, Research Result. Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 7 (2), 31-40. https://doi.org/10.18413/2313-8912-2021-7-2-0-4(In Russian)