Corpus linguistic exploration of Russian-Vietnamese mutual perceptions

Abstract

Despite long-term fruitful relations between Russia and Vietnam, there is still a need for studies that would deepen intercultural understanding between the two peoples. In this paper, Russian-Vietnamese mutual perceptions are analyzed relying on corpus linguistic methods. Data collection was conducted in the course of a preceding study aimed at the reconstruction and investigation of mutual representations of the Russian and Vietnamese peoples through experimentally obtained ethnic portraits and self-portraits of the two respective nations. Here, the empirical data of the collected data is further deeper examined by corpus linguistic tools (Sketch Engine, Atlas.ti). In order to gain a more comprehensive picture of the two nations’ mutual and self-perceptions, Russian-Vietnamese pairs of characteristics were identified and semantically contrasted to Russian and Vietnamese reference corpora as common parts of mutual perceptions. Connotational differences of the studied characteristics were identified, analyzed, and categorized and unique traits of the Russian and Vietnamese mutual and self-perceptions were identified and investigated. Collocations and thesauri of the relevant characteristics were examined, complemented by the corpus-based analysis of the two nations’ perceptions. The obtained results suggest that the Top-10 most typical common traits of mutual and self-perceptions of the two peoples comprise noteworthy semantic differences. The research confirmed the effectiveness of the complementary application of the questionnaire-based and the corpus linguistic methods. It is concluded that the combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches gives a more comprehensive picture of how the ethnic portraits and self-portraits are reflected in languages and cultures.

Keywords: Mutual perceptions, Intercultural communication, Corpus linguistics, National/ethnic portraits and self-portraits, Russian-Vietnamese dialogue

Introduction

The systematic investigation of mutual perceptions between representatives of different cultures and nations is a pivotal part of intercultural studies aiming at facilitating intercultural encounters and preventing misunderstanding, miscommunication, and intercultural conflicts. Previous studies performed a wide array of research in this field with different scopes, in different relations such as, for instance, focusing on the US-China international relations (Jisi et al., 2020), on Japanese-German mutual perceptions and their influence on bilateral relations (Saaler et al., 2017), on Jewish-Arab mutual perceptions (Mollov, 2016), on Brazilian-Argentinian international security issues (Oelsner, 2003) to mention but a few of the extensive academic literature.

Russia, the largest country in the world covering over 17 million square kilometers of land, representing 11% of the total world's landmass, with a population of 144 million, and Vietnam, the sixteenth most populous country in the world with a population of over 103 million people were also studied from the perspective of mutual perceptions with other nations and cultures including the relations of Russia-France (Muratbekova-Touron, 2011), Russia-Japan-China (Houghton et al., 2013), Russia-Central Asia (Laruelle, 2021), Vietnam-China (Endres, 2015) or Vietnam-Korea (Seo et al., 2019), etc.

A major part of the research on mutual perceptions relies on the well-established concepts of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination that constitute widely accepted theoretical and conceptual frameworks for studying this aspect of intercultural communication (Allport, 1935; Adler, 1993; Baker, 2014; Stewart et al., 2021). In the present study, the authors leverage another theoretical background, which is rooted in the works of the scholars of the Moscow School of Psycholinguistics (Leontiev, 1993; Sorokin, 1994; Tarasov, 1996; Ufimtseva, 1996) and apply the concept of ethnic portraits and self-portraits. From their perspective, ethnic portraits are understood as the construct of perceptions of another group of people obtained through linguistic data, while ethnic self-portraits are interpreted as a similar concept referring to the self-perception of a group of people. In this research, the portraits and self-portraits of the Russians and the Vietnamese serve as the object of the study.

This paper relies on a preceding empirical, questionnaire-based research of Russian–Vietnamese mutual perceptions from linguistic and cultural perspectives (Markovina et al., 2021, 2022). The empirical linguistic data collected during the previous stage of the research are further investigated with corpus linguistic methods. A possible further development of the traditional psycholinguistic methods (Leonard et al., 2019), comparative analysis of corpora data, is suggested as a tool for investigation of lexical items that express cultural concepts in different languages. Therefore, the aim of the study was to shed the light on the culture- and language-specific differences of the Russian and Vietnamese lexical items that the respondents most frequently used to describe the Russian and the Vietnamese peoples. The hypothesis of the study is that behind the lexically equivalent words in different languages there is a culture-specific content. Based on this assumption, these words should be understood as quasi-equivalent.

To our knowledge, it is the first attempt to apply corpus linguistic approach to the investigation of the formation of ethnic portraits and self-portraits from the linguocultural perspective.

Materials and Methods

Primary data collection was conducted in the frame of a previous study (Markovina et al., 2022) in the form of a questionnaire-based survey. Homogeneous respondent groups of 100–100 university students in Moscow and Hanoi were selected (age: 17-25 years), with respondents speaking Russian and the Vietnamese languages as mother tongues respectively. Participation in the research was voluntary. The online questionnaire aimed at describing the ethnic portraits and self-portraits of the Vietnamese and Russian nations in two categories: characteristicportraits and personified (anthroponymic) portraits. The results were arranged into frequency lists and analyzed semantically.

In the above mentioned preceding study, the authors identified similarities and differences in the ethnic portraits and self-portraits of the two nations including overlapping characteristics such as courage (смелость/ dũng cảm); hospitality (гостеприимство/ hiếu khách); industriousness (трудолюбие/ cần cù); intelligence (ум/ thông minh); and kindness (доброта/ tốt bụng), as well as differing perceptions. The latter include, for example, Russians seeing Vietnamese as industrious, kind, and cheerful, while the Vietnamese self-perception consisting of such pivotal characteristics as united, hard-working and patriotic. In this same study, the authors utilized the Schwartz Theory of Basic Human Values to further explain the obtained results, yielding considerable cross-cultural differences between Russians and Vietnamese in the perception of openness to change and conservation.

In this paper, the collected linguistic data on characteristicportraits and self-portraits is further investigated and analyzed by corpus linguistic methods. Corpus linguistics, as a relatively new but well-established field of linguistics, enables the researchers to investigate a large amount of text data (linguistic corpora) utilizing computer-aided methods (Tognini-Bonelli, 2001; McEnery and Hardie, 2011).

The primary dataset was scrutinized using Sketch Engine, an online corpus linguistic research tool (Kilgarriff et al., 2004) via the various functions of this online analytic instrument. The five most typical common traits of mutual and self-perceptions, namely kindness [доброта/tốt bụng]; courage [смелость/dũng cảm]; hospitality [гостеприимство/hiếu khách]; industriousness [трудолюбие/cần cù]; and intelligence [ум/thông minh] were semantically contrasted in both languages, applying the thesaurus function of the software, which automatically generates a list of synonyms or words that belong to the same semantic category (field). The results were visualized by Atlas.ti online tool[1].

The Russian and Vietnamese reference corpora used in the study are similar in the source text genres as both are Internet-based corpora mainly consisting of Internet articles. The Russian reference corpus is Russian Web 2011 (ruTenTen11) includes 18.2 billion words, while the Vietnamese corpus is the Vietnamese Web (VietnameseWaC) and contains 106.4 million words. Both corpora are similar not only in the source text genres, but also in encoding (both encoded in UTF-8, cleaned, and deduplicated), in tagging (both tagged by RFTagger and TreeTagger), as well as in the period of data collection (the Russian corpus was compiled in 2011, the Vietnamese one in 2010).

The obtained data were arranged according to LogDice scores rather than the word frequencies. This measure is also used for identification of co-occurrence of two lexical items; however, it is preferable in case of large corpora, as it is not affected by their size. Described as a “lexicographer-friendly association score” (Rychlý, 2008: 6), LogDice, unlike other statistics, does not rely on an expected frequency of the word occurrence in the corpus (Gablasova et al., 2017). Moreover, for the purpose of the current study, the strength of collocation (i.e., typicality), denoted by the LogDice score, is preferable over the word frequency as the authors are more interested in the qualitative rather than quantitative analysis.

Results

Common traits of Russian and Vietnamese perceptions

Based on the primary data obtained in the course of the preceding research (Markovina et al., 2022), common traits of Russian and Vietnamese perceptions were identified in three dimensions: 1. Self-perception of the two nations; 2. Russians’ perception by themselves and by Vietnamese respondents; 3. Vietnamese’s perception by themselves and by Russian respondents, detailed as follows.

The common traits of Russian and Vietnamese self-perceptions include: courage (смелость/ dũng cảm); hospitality (гостеприимство/ hiếu khách); industriousness (трудолюбие/ cần cù); and intelligence (ум/ thông minh). The main overlappings between the Russian self-perception and how the Vietnamese see the Russians are as follows: kindness (доброта/ tốt bụng); courage (смелость/ dũng cảm); hospitality (гостеприимство/hiếu khách); and intelligence (ум/ thông minh). Finally, the common trait of Vietnamese self-perception and how the Russians see the Vietnamese is: industriousness (cần cù/ трудолюбие).

After sorting out duplicate results, the following five pairs of words emerged as the most relevant linguistic appearances of common perceptions. These pairs were selected for further semantic analysis detailed in the below chapters:

1. courage (смелость/ dũng cảm);

2. hospitality (гостеприимство/ hiếu khách);

3. industriousness (трудолюбие/ cần cù);

4. intelligence (ум/ thông minh);

5. kindness (доброта/ tốt bụng).

Preference was given to the noun forms (e.g., courage over courageous). It needs to be noted that in the Vietnamese language the noun and adjective forms are often identical, e.g. dung cảm might mean both courage and courageous depending on the context. However, they were translated as nouns for the purpose of the current study, as this allows for direct comparison with the Russian corpus data and the results of the previous questionnaire-based study.

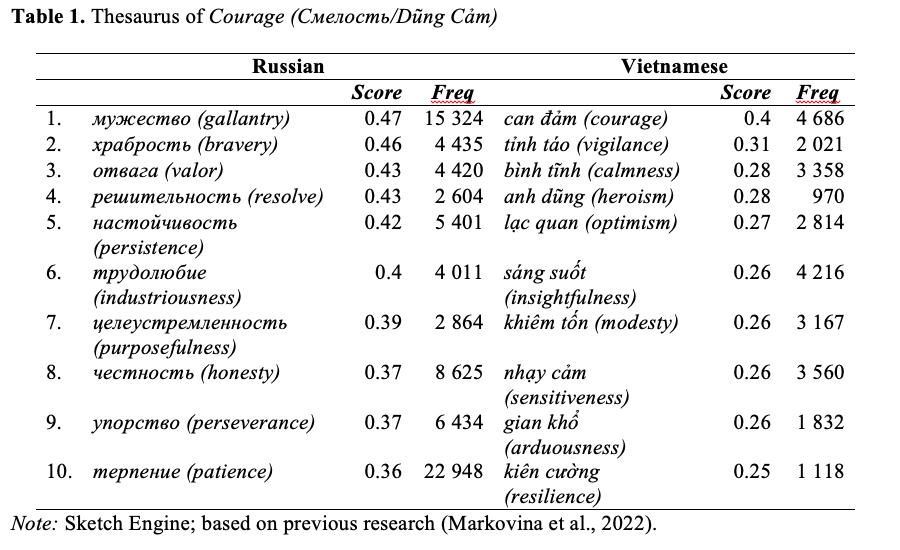

The corpus linguistic analysis of the Russian word смелость (courage) and its Vietnamese equivalent dũng cảm (courage) was performed using the thesaurus building function of Sketch Engine. Comparative results can be seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Thesaurus of Courage (Смелость/Dũng Cảm)

Note: Sketch Engine; based on previous research (Markovina et al., 2022).

This and the subsequent thesauri contain quasi-synonyms of the selected word occurrences in the investigated corpora. These synonyms (as appear in Tables 1-5) are identified relying on the context of each word in the ruTenTen11 and the VietnameseWaC reference corpora, respectively. As Table 1 suggests, similar core semantic features of the words смелость and dũng cảm (both translated as courage) were identified in the two languages, as demonstrated by such lexemes as храбрость (bravery) and can đảm (courage); or трудолюбие (industriousness), vis-à-vis gian khổ (arduousness), and настойчивость (persistence) or упорство (perseverance) vis-à-vis kiên cường (resilience). Differences can also be grasped in the Top-10 results including Russian language users detailing courage (смелость) through lexemes мужество (gallantry), целеустремленность (purposefulness), and честность (honesty), while the Vietnamese context refers to tỉnh táo (alertness, vigilance), bình tĩnh (calmness), anh dũng (heroism), lạc quan (optimism), sáng suốt (insightfulness), nhạy cảm (sensitiveness), and khiêm tốn (modesty).

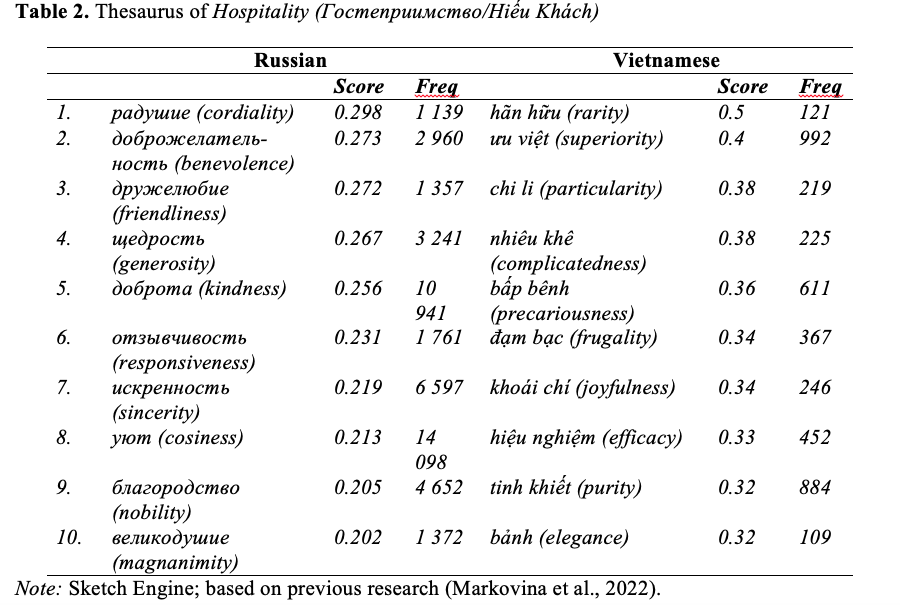

Table 2. Thesaurus of Hospitality(Гостеприимство/Hiếu Khách)

Similarly, the semantic field of the word hospitality (гостеприимство/ hiếu khách) was investigated applying the Thesaurus building function of the Sketch Engine online analytical tool in both languages (Table 2). The Russian equivalent, гостеприимство, emerged as an exclusively positive notion that can be detailed with the nouns радушие (cordiality), доброжелательность (benevolence), дружелюбие (friendliness), щедрость (generosity), доброта (kindness), and so on. Meanwhile, a noteworthy number of perceptions are connected to the Vietnamese equivalent hiếu khách (hospitality) including nhiêu khê (complicatedness), bấp bênh (precariousness), and đạm bạc (frugality). These notions can hardly be linked to the Russian idea of hospitality, thus, suggesting cultural differences in understanding of the seemingly equivalent idea of hospitality.

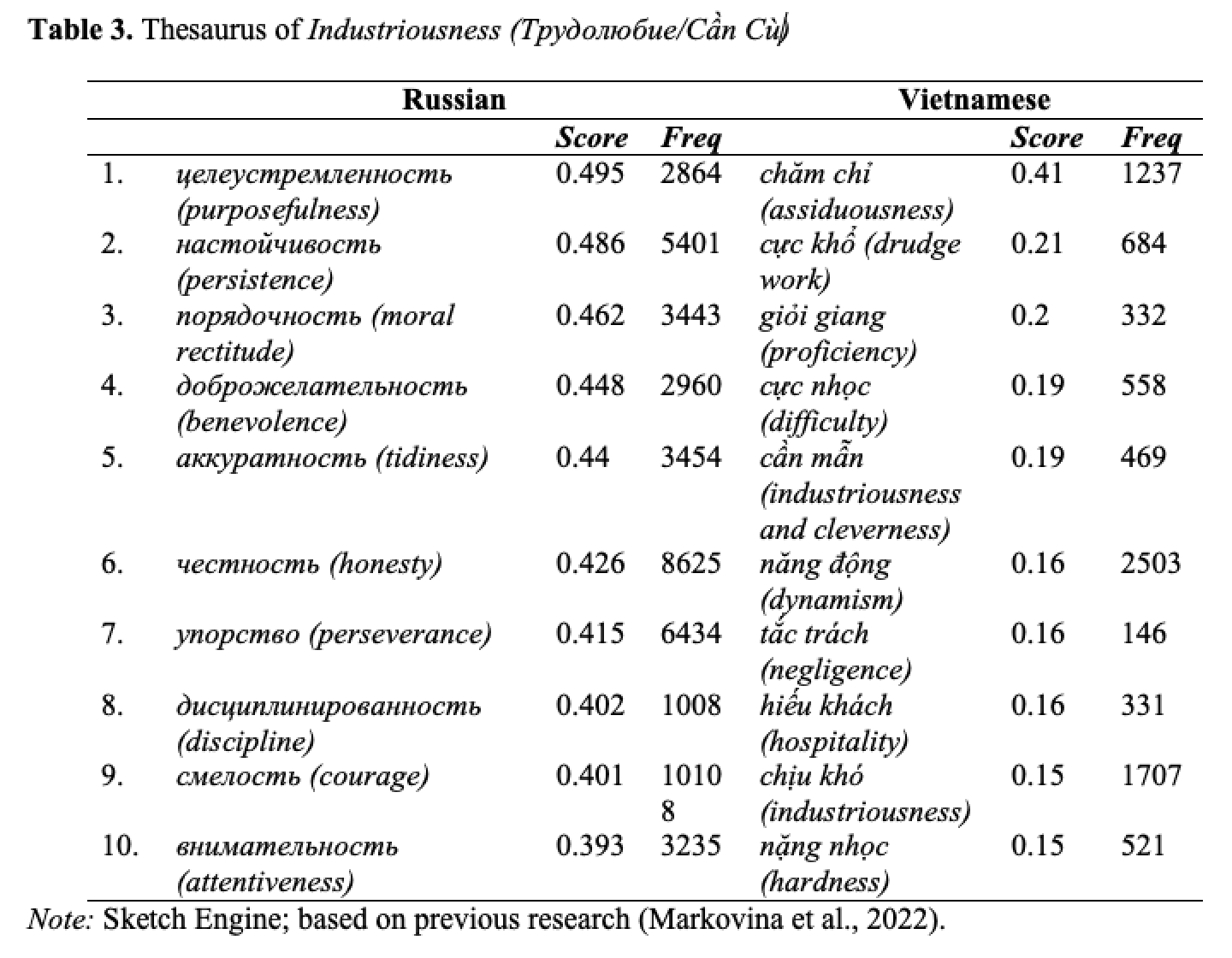

Table 3. Thesaurus of Industriousness (Трудолюбие/Cần Cù)

The Russian notion of трудолюбие (industriousness) (see Table 3) can be characterized based on the synonymic context of the word by several individual qualities including целеустремленность (purposefulness), порядочность (moral rectitude), честность (honesty), дисциплинированность (discipline), and внимательность (attentiveness). The Vietnamese results refer to a number of closely related notions, such as chăm chỉ (assiduousness), cực khổ (drudge work), cần mẫn (industriousness and cleverness), chịu khó (industriousness), and nặng nhọc (hardness).

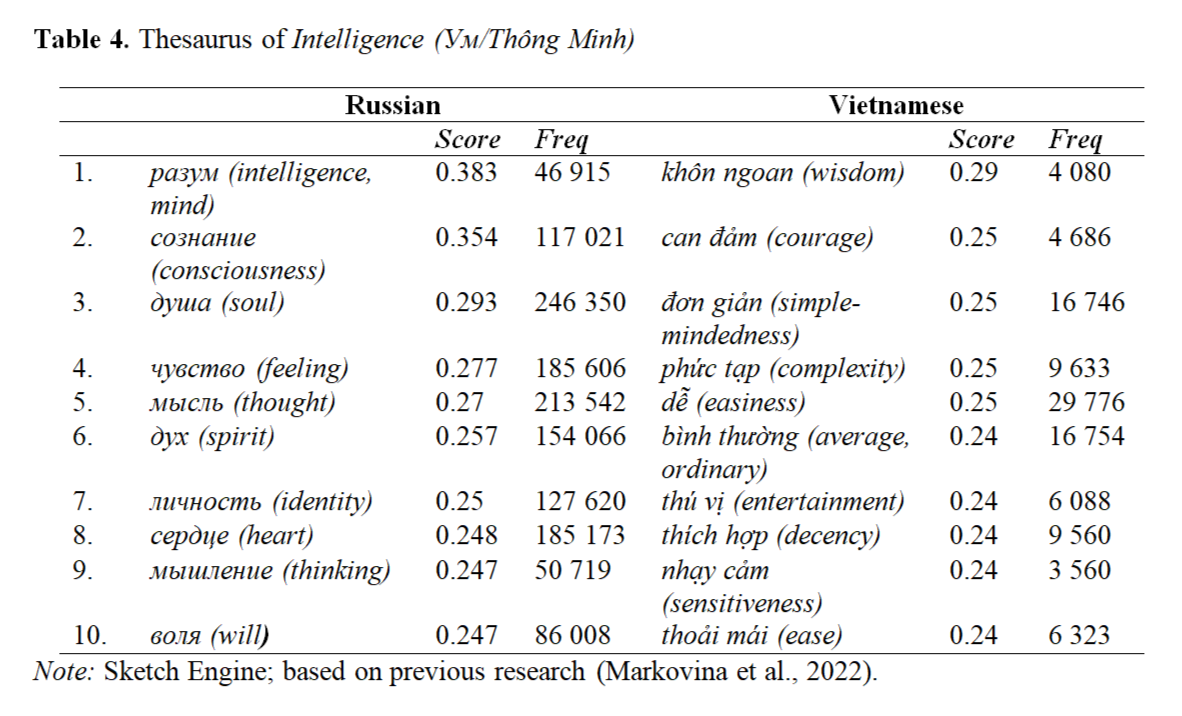

Table 4. Thesaurus of Intelligence (Ум/Thông Minh)

Note: Sketch Engine; based on previous research (Markovina et al., 2022).

As Table 4 suggests, the Russian concept of ум (intelligence) is semantically intertwined with consciousness (сознание), feelings (чувство) and thinking (мышление). Furthermore, it seems to be closely connected with the soul (душа), the spirit (дух) and the heart (сердце). In the Vietnamese semantic field of thông minh (intelligence) notions expressing easiness are strongly present, including such words as đơn giản (simple-mindedness), dễ (easiness), bình thường (average, ordinary), and thoải mái (ease). This exemplifies yet another culture-specific understanding of the idea of intelligence.

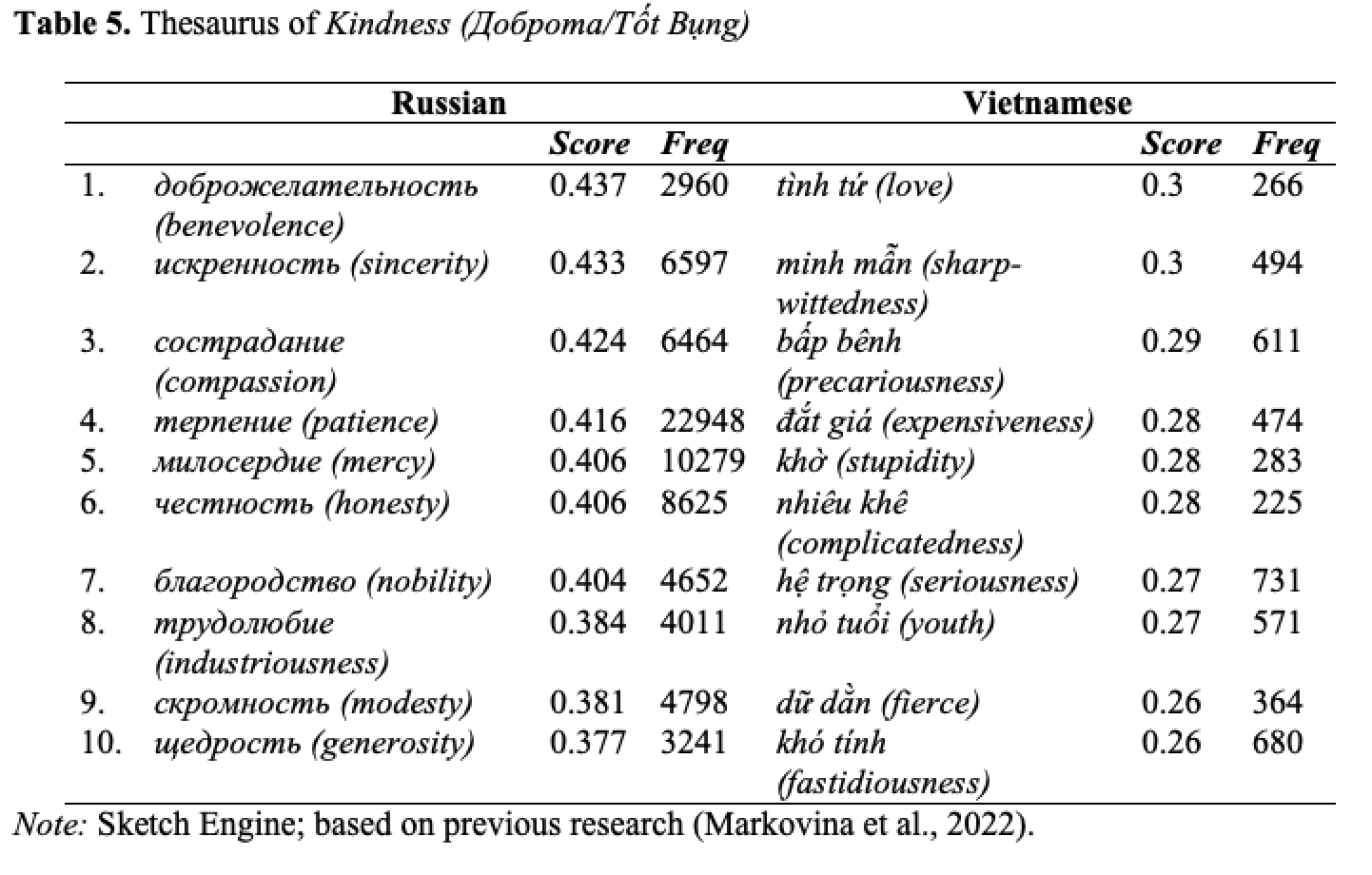

Table 5. Thesaurus of Kindness (Доброта/Tốt Bụng)

Note: Sketch Engine; based on previous research (Markovina et al., 2022).

The Russian data set suggests that the notion of kindness (доброта) is semantically connected to terms expressing personal qualities, including доброжелательность (benevolence), искренность (sincerity), честность (honesty), благородство (nobility), and щедрость (generosity) (see Table 5). Sixty percent of the Top-10 synonyms of the Vietnamese word kind/kindness (tốtbụng) refer to a less positive perception of the notion expressed by such lexemes as bấp bênh (precariousness), đắtgiá (expensiveness), khờ (stupidity), nhiêukhê (complicatedness), dữdằn (fierce), khótính (fastidiousness).

Keyword in context analysis

Unlike the analysis of the common traits of Russian and Vietnamese perceptions that was based on the results of the previous study, subsequent investigation of the two nations’ mutual and self-perceptions utilizing the linguistic data contained in the above mentioned ruTenTen11 and VietnameseWaC linguistic corpora was attempted without the reference to the previous primary research.

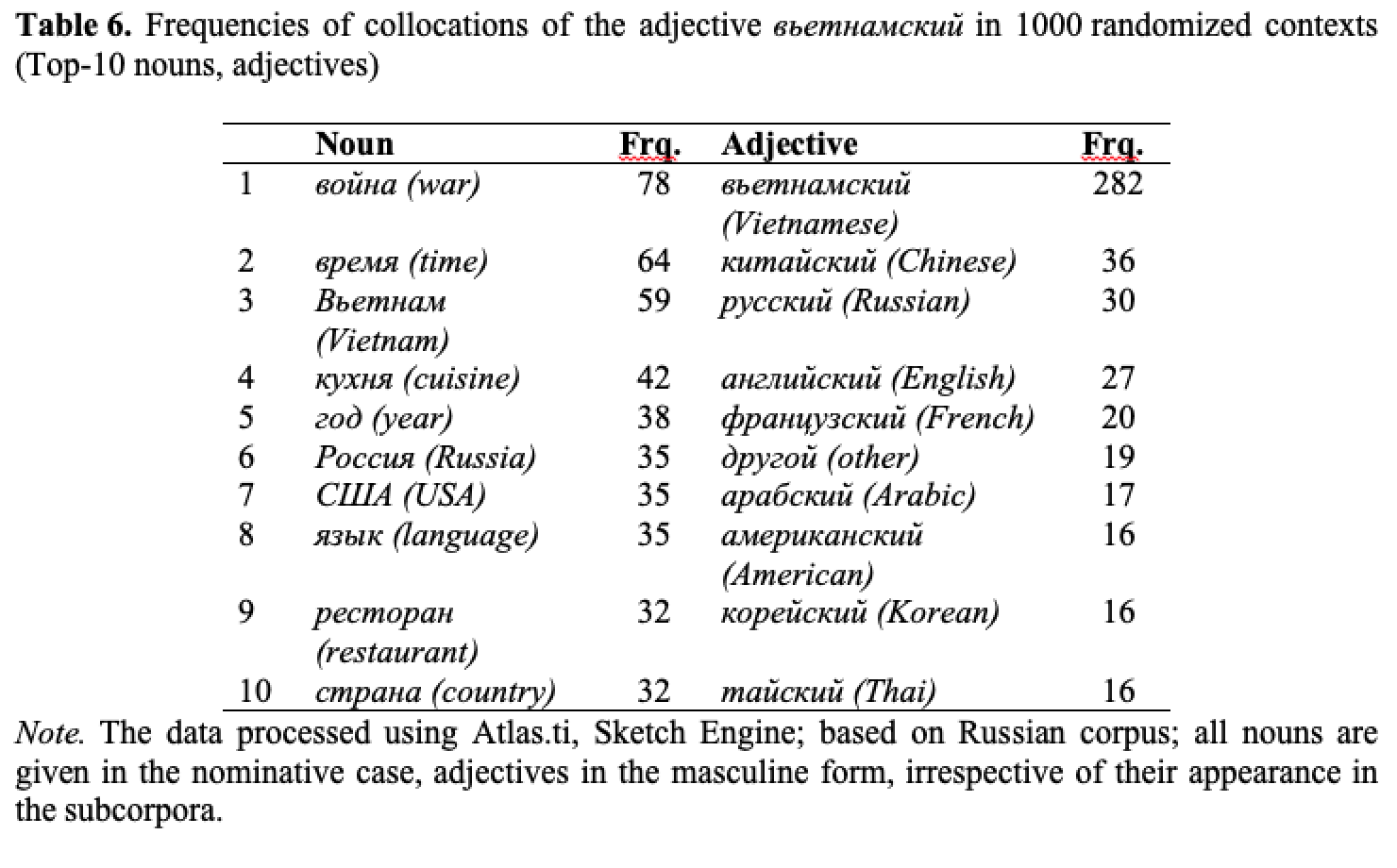

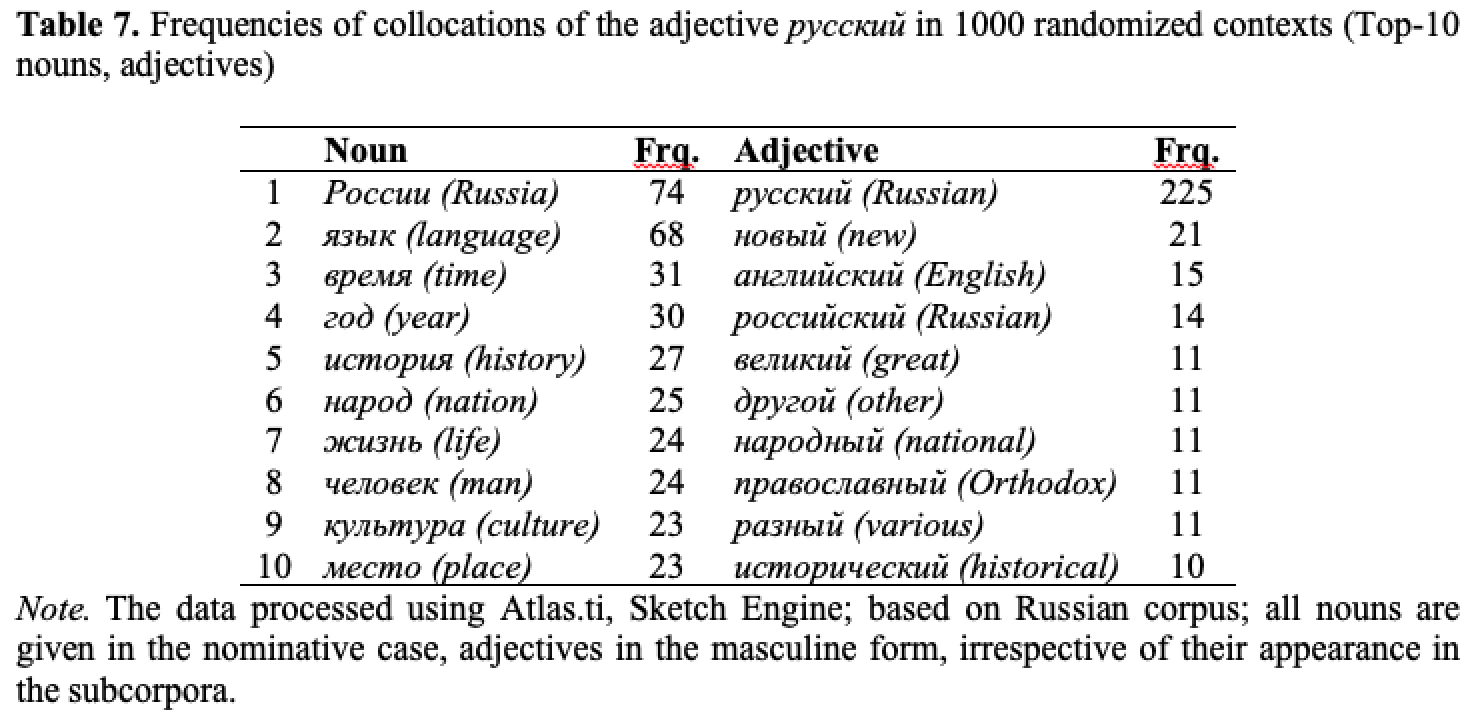

Tables 6-9 display results of a keyword in context analysis of the words Vietnamese (вьетнамский, Việt) and Russian (русский, Nga) based on the data of the two selected large-size linguistic corpora ruTenTen11 and VietnameseWaC. The objective of this second, complementary investigation was to obtain a clearer and more comprehensive picture of the perception of these nations in all four investigated perspectives: 1 how Vietnamese people see Russians; 2. how they see themselves; 3. how Russians perceive Vietnamese; and 4. how they perceive themselves. In order to fine-tune the results relying on the previous research as detailed above, the two corpora were further investigated applying the following methodology. The context of the keywords вьетнамский, Việt (Vietnamese), and the keywords русский, Nga (Russian), were collected using the Concordance function of Sketch Engine, which allows to search for words and phrases and displays the results in context as concordance.

The contexts of the four keywords were collected (вьетнамский and русский in the Russian corpus and Việt and Nga in the Vietnamese corpus). A total of 1000 randomized contexts were selected and compiled in the case of each keyword, with 100 words from the vicinity of every keyword occurrence. The Sketch Engine tool was utilized for the data collection that were arranged into four respective subcorpora and were analyzed using the Atlas.ti online tool and its Word List function. This function arranges the words of the corpora in order of frequency. Subsequently, the Top-10 most frequent nouns and adjectives were collected (see Tables 6-9). These are considered to be good markers of the context of the keywords denoting the Vietnamese and the Russian nationalities, thus provide us a clearer picture of the respective mutual and self-perceptions. Word forms including suffixes were kept in the same form as they appear in the investigated corpora.

Table 6. Frequencies of collocations of the adjective вьетнамский in 1000 randomized contexts (Top-10 nouns, adjectives)

Note. The data processed using Atlas.ti, Sketch Engine; based on Russian corpus; all nouns are given in the nominative case, adjectives in the masculine form, irrespective of their appearance in the subcorpora.

The Russian perception of Vietnamese is closely connected to the notion of war leading the frequency list with 78 occurrences. Three country names are included in the Top-10 nouns: besides the two investigated countries Vietnam (59) and Russia (35), the United States appears 35 times as well. Vietnamese language, cuisine, and restaurant are also substantial parts of the perception of Vietnamese in Russia. Most of the typical adjectives occurring in the vicinity of вьетнамский (Vietnamese) include other nationalities, eight within the Top-10 results including Chinese, Russian, English, French, Arabic, American, Korean, and Thai.

Table 7. Frequencies of collocations of the adjective русский in 1000 randomized contexts (Top-10 nouns, adjectives)

Note. The data processed using Atlas.ti, Sketch Engine; based on Russian corpus; all nouns are given in the nominative case, adjectives in the masculine form, irrespective of their appearance in the subcorpora.

A noteworthy trait of the Russian self-perception is history (история), which appears in both the noun and the adjective form (история and исторический, respectively), similar to nation which was also collected in both the noun (народ) and the adjective (народный) form. Language (язык) and culture (культура) seem to be dominant nouns in the observed contexts too, with 68 and 23 occurrences, respectively. Orthodox Christian (православный) religion appears in the Top-10 adjectives. Furthermore, Russians perceive themselves as great (великий).

Table 8. Frequencies of collocations of the adjective nga in 1000 randomized contexts (Top-10 nouns, adjectives)

Note. The data processed using Atlas.ti, Sketch Engine; based on Vietnamese corpus.

Based on the context analysis, Vietnamese see Russians as great/big (lớn), tall (cao), and strong (mạnh). Americans (mỹ) and French (pháp) also appear in the Top-10 most typical contexts of Russians in Vietnamese texts. Besides people (người) and country (nước, quốc) taking the top positions of noun contexts of Russians, war (chiến tranh) was identified as the fourth most frequent noun in the randomized contexts. Nhà (house/home) is also part of the Russians’ perception in Vietnam.

Table 9. Frequencies of collocations of the adjective việt in 1000 randomized contexts (Top-10 nouns, adjectives)

Note. The data processed using Atlas.ti, Sketch Engine; based on Vietnamese corpus.

Vietnamese contexts indicate a strong presence of nouns indicating people (người, dân), language (tiếng, ngôn ngữ), and country (nước, quốc). Similarly to Vietnamese perception of Russians, nhà (house/home) is among the Top-10 nouns identified. Further to that, Vietnamese see themselves as great (đại, lớn) and equal (equal, bằng).

Discussion

Common traits of Russian and Vietnamese perceptions

As already mentioned, the authors attempted to prove that behind the lexically equivalent words in different languages there is a culture-specific content. To demonstrate this, the corpus linguistic approach was applied to the analysis of the lexically equivalent words in the Russian and the Vietnamese languages. These lexically equivalent words had been obtained at the first stage of the research aimed at collecting the characteristics of the Russian and the Vietnamese ethnic portraits and self-portraits, using questionnaire-based approach.

Corpora are collections of natural language data used for specific purpose. They can provide invaluable insights into the language in use, as they capture grammatical (Jones and Waller, 2015), lexical (Moon, 2010), and other language-related information. However, to our knowledge, publications devoted to the investigation of linguocultural concepts across different languages and cultures by corpus linguistic methods are scarce (Vaičenonienė, 2001; Rozumko, 2012; Rebechi, 2013; Ge, 2022). In fact, we support the postulate that a general corpus can be viewed as “a repository of cultural information about a society as a whole” (Hunston, 2002: 117). Digitized corpora allow researchers to reveal patterns that exist in language and “embody particular social values and views of the world” (Stubbs, 1996: 158), thus, making corpus analysis an important tool for revealing meanings behind the words that contribute to “the routine transmission of cultural knowledge” (Stubbs, 2006: 33). In this work we attempted to apply corpus linguistic methods to the comparative investigation of the processes of the formation of ethnic portraits and self-portraits from the linguocultural perspective.

As Table 1 suggests, the notion of courage (смелость) as an umbrella term for the group of semantically similar notions demonstrates a partial overlap between the Russian corpus data and the data obtained from the respondents. The first three most frequent words that denote courage (смелость) in the Russian language are: 1. мужество (gallantry – as in medal for gallantry); 2. храбрость (bravery); and 3. отвага (valor).

It should be highlighted that the words mentioned have the same rank order in both questionnaire-based and corpus-based data, with courage (смелость) being the most frequent one in the group. This additionally confirms the right choice of the word as an umbrella term for the group of quasi-equivalents in our previous experiment (Markovina et al., 2021; 2022).

However, the data obtained from the questionnaire-based stage also include four semantically related words not observed in the corpus data. These are самоотверженность (self-sacrifice), героизм (heroism), бесстрашие (fearlessness), and умение не сдаваться (the ability not to give up). For the respondents in our previous research (Markovina et al., 2022) these words represent the most common synonyms to the word смелость (courage), including the definition of the quality, i.e., умение не сдаваться (the ability not to give up).

Despite close semantic relatedness and somewhat synonymic usage, these words have different shades of meaning. For example, бесстрашный человек (fearless person) feels no fear, whereas courageous (смелый), valorous (храбрый), gallant (мужественный), and brave (отважный) keeps fear under control.

In the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language[2] the word смелость (courage) is defined as “Отвага, решимость, смелое поведение” (valor, resolve, brave behavior), so the definition is essentially given through synonyms, one of which – отвага (valor) – occurs in both datasets as the third most frequent word describing the category. Another word in the definition (решимость (resolve)) is a paronym with решительность (resolve) that can be found in the corpus data: the difference is essentially negligible. The last expression смелое поведение (courageous behavior) contains the qualitative adjective from the noun that it defines.

It should also be noted that some words from the Russian part of Table 1 at first glance have no semantic relation to смелость (courage); they are rather descriptive characteristics of a courageous person, who might also demonstrate настойчивость (persistence), трудолюбие (industriousness), целеустремленность (purposefulness), честность (honesty), упорство (perseverance), and терпение (patience)

Similarly to the Russian data set, the Vietnamese notion of dũng cảm (courage) is related to both can đảm (brave) and anh dũng (heroism).

The comparison of data from the corpus and the Vietnamese part of the questionnaire-based study demonstrates a single overlapping characteristic anh dũng (heroism) between the two data sets. For the Vietnamese respondents, courage is also linked to bravery (lòng dũng cảm), fearlessness (gan dạ), and to indomitability (bất khuất).

Further to that, it is also related to bình tĩnh (calmness) and tỉnh táo (alertness, vigilance), thus highlighting the attitude of the Vietnamese people to the circumstances under which they show courage. The rest of the characteristics – sáng suốt (insightfulness), khiêm tốn (modesty), nhạy cảm (sensitiveness), gian khổ (hardship), and kiên cường (resilience) – might be attributed to any decent person.

The notion of hospitality in the web-corpora has been previously examined (Markovina et al., 2023) and is often regarded as a national characteristic. In the corpus, this noun is often combined with the respective adjectives (e.g., русское гостеприимство (Russian hospitality), абхазское гостеприимство (Abkhaz hospitality), denoting a nation, or восточное гостеприимство (Eastern hospitality), denoting a region) or adjectives that add shades of meaning (e.g., радушное гостеприимство (cordial hospitality), хлебосольное гостеприимство (good table hospitality), щедрое гостеприимство (unstinted hospitality), etc.). There is also a number of comparative adjectives that describe the degree of hospitality, e.g., непревзойденное гостеприимство (unsurpassed hospitality), исключительное гостеприимство (unparalleled hospitality) (Markovina et al., 2022; 2023).

We assume that the frequency of the discussed collocations found in the corpus and their diversity emphasize the value of the notion (personal quality/character trait) for the particular culture (Ge, 2022).

The Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language defines гостеприимство (hospitality) as “Радушие по отношению к гостям, любезный прием гостей” (Cordiality towards guests, amiable welcome of guests), thus, confirming that радушие (cordiality) is indeed one of the most important qualities that describe гостеприимство (hospitality). This is supported both by the corpus data and the results of our previous studies, where радушие (cordiality), for example, was one of the qualities linked with гостеприимство (hospitality) (Markovina et al., 2021; 2022).

Indeed, a hospitable person is the one who should demonstrate доброжелательность (benevolence), дружелюбие (friendliness), доброту (kindness), and отзывчивость (responsiveness) towards guests. Щедрость (generosity), as in щедрое гостеприимство (generous hospitality), traditionally characterizes the host’s attitude towards the provision of guests with food and drinks, искренность (sincerity), and the absence of hypocrisy.

It is of interest that уют (cosiness), found in the corpus data, is also an important aspect of Russian hospitality. Welcoming guests into a place that gives a feeling of comfort, warmth, and relaxation is an essential part of the meaning of the Russian word гостеприимство (hospitality).

Both благородство (nobility) and великодушие (magnanimity) are rarely used towards guests; these nouns describe a person of high virtue.

At the previous stage of the current research, two other qualities related to гостеприимство (hospitality) – добродушие (good nature) and жизнелюбие (love of life) – were provided by the Russian respondents. The Vietnamese respondents linked hiếu khách (hospitality) to thân thiện (friendliness), nhân ái (benevolence), and niềm nở (attentiveness). For a detailed discussion, please see (Markovina et al., 2023).

Industriousness (трудолюбие) is widely recognized as one of the typical characteristics of the Vietnamese people. This is also documented in various works on Vietnamese traditional values (Duy, 2021; Nguyen, 2021).

Needless to say that целеустремленность (purposefulness), настойчивость (persistence), and упорство (perseverance) are found side by side in those who demonstrate трудолюбие (industriousness), which means that трудолюбие (industriousness) is valued in the culture as a means of achieving some goal.

Another group of semantically related nouns аккуратность (tidiness), внимательность (attentiveness), and дисциплинированность (discipline) can be considered as the skills that are required to perform high quality work.

Other characteristics found in the Russian corpus – порядочность (moral rectitude), доброжелательность (benevolence), and смелость (courage) – do not seem to be directly related to трудолюбие (industriousness), as they just describe a decent person.

Two of the four words related by the Russian respondents to трудолюбие (industriousness) are derivatives of the root word труд (labor): трудящийся (working person) describes any person, who is involved in work activities, whereas трудоголик (work addict/workaholic) is understood quite literally: a person who is addicted to work. Another response – производительность (performance) – is obviously related to the work performance. It can be seen that the responses of the survey participants differ from the corpus data which can be partially explained by the fact that most of the Russian responses are derivatives of трудолюбие (industriousness) (Markovina et al., 2021; 2022).

The data that emerged from the Vietnamese corpus confirm the data obtained in the previous questionnaire-based study: chăm chỉ (assiduousness) is closely related to cần cù (industriousness). Moreover, we can distinguish the group of three close synonyms: chịu khó (industriousness), nặng nhọc (industriousness), cần mẫn (industriousness and cleverness), and cực khổ has a qualitative shade of doing drudge work. The corpus data also confirm the link between giỏi giang (proficiency) and cần cù (industriousness). The năng động (dynamism) implies active attitude of the Vietnamese towards work. One entry from Table 3, hiếu khách (hospitality) might often co-occur with cần cù (industriousness) in the Vietnamese corpus because both are considered the virtues of the Vietnamese people.

Two notions found in the Vietnamese corpus are of particular interest as they may denote the attitude of the Vietnamese towards cần cù (industriousness). The first is cực nhọc (difficulty), which from the Vietnamese perspective seem to go together with cần cù (industriousness). The second – tắc trách (negligence) – is another quality that may accompany the process of hard work.

It should be noted, that compared to the Russian self-perceptions and their perceptions by Vietnamese, there are much less overlapping characteristics between Vietnamese perceptions by Russians and Vietnamese self-perceptions. The above described trait – cần cù (industriousness) – was the only such characteristic identified in the preceding study (Markovina et al., 2022). The principal reason for this outcome is the fact that most Russians have very limited knowledge of Vietnamese people in general as reflected in their most frequent answer “I don’t know”, amounting to 20% of all replies (Markovina et al., 2021).

In the Russian data, both ум (intelligence, mind) and разум (intelligence) denote similar concepts but have different shades of meaning: the former emphasizes the quantitative aspect of knowledge accumulation, whereas the latter stresses the qualitative results of the same process. However, the adjectives typically combined with these nouns add some new shades of meaning to ум (intelligence, mind). It may denote the speed of the process, e.g., быстрый ум (agile mind); its performance, e.g., острый ум (sharp mind); or even denote a type of intelligence that characterizes a particular type of people, e.g., русский ум (Russian mind) or крестьянский ум (peasant’s mind).

According to the corpus data, the strongest connection is between ум (intelligence, mind) and сознание (consciousness). Similar to ум (intelligence, mind), сознание (consciousness) can be attributed to an individual and to people in general, like in массовое сознание (collective consciousness). However, they have different connotations. In fixed expressions they may contrast each other; consider: живость ума (lively mind) and спутанностьсознания (mental confusion). A pair of words, мысль (thought) and мышление (thinking), share common root and denote a unit of a tool of thinking (thought) and the process of thinking. However, ум (intelligence, mind) is usually used in a much broader sense than мышление (thinking).

As can be seen from Table 4, ум (intelligence, mind) is related to сердце (heart). The latter can be understood in some contexts as the sum of feelings almost antonymous to intelligence, as in чувствовать сердцем, но не понимать умом (feeling with one’s heart, and not understanding with one’s mind). Ум (intelligence, mind), being a purely abstract concept, can represent an imaginary organ with particular localization (the head), hence the typical hand gesture of pointing at the head while saying выжил из ума (out of mind). Another abstract concept, душа (soul), is also often contrasted with ум (intelligence). As the corpus data show, both душа (soul) and сердце (heart) can be used almost interchangeably in the general discourse related to one’s feelings. Consider the following examples: душа/сердце болит (sick at heart/soul) and душа/сердце радуется (heart/soul fills with joy); согревает душу/сердце (warm the cockles of the heart/soul); завладеть душой/сердцем (engage one's heart/soul); чистый душой/сердцем (pure in heart/soul).

It should be noted that интеллект (intellect), understood as a cognitive ability similar to ум (intelligence, mind), often used as a term, is not found in Top-10 corpus data, though a single response is found in the results obtained in the survey (Markovina et al., 2021, 2022). The respondents also provided two peculiar characteristics of the Russians. Мудрость (wisdom) is not among the results obtained using Russian corpus, but the Vietnamese corpus data suggest a close (and somewhat obvious) association between khôn ngoan (wisdom) and thông minh (intelligence). The other characteristic mentioned by the respondents and not found in the corpus, cмекалка (quick wit), is defined in the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language as “Сообразительность, догадливость, способность быстро понять, смекнуть что-нибудь” (Ingenuity, quick wits, the ability to quickly understand something). This opens the door for speculation that the Russians often think out-of-the-box and favor the speed of thinking process, whereas the Vietnamese intelligence is deeply rooted in the wisdom, i.e., in the body of knowledge that develops over time. Indeed, literary sources confirm the importance of the wisdom for the Vietnamese society (Tho, 2016), particularly in the framework of Confucianism (Thu et al., 2021) that extends far beyond the religious views and social ethics. As defined by Prokhorov and Sternin, cмекалка (quick wit) is a “purely Russian word: the ability to adapt, replace, use an object for other purposes, in a function unusual for it, in order to compensate for the lack of spare parts, tools, material resources, etc. This is the ability to adapt, find a way out, which is a means of compensating for the current principle of "avos’” (faith in sheer luck) (Prokohorov and Sternin, 2006: 60). This also confirms that this characteristic might be an intrinsic value of the Russian culture.

It is of interest that only one notion – khôn lỏi (trickiness) – related to thông minh (intelligence) can be found in the data obtained from the Vietnamese respondents and a single lexical unit that contrasts thông minh (intelligence) is found in the Vietnamese corpus data: đơn giản (simple-mindedness). The latter may denote uncomplicated, yet efficient thinking process that, akin to Occam's razor, takes into account only important information, but disregards everything non-essential. However, further investigations are required to support this assumption.

Another common characteristic of the Russian self-perception and the Vietnamese perception of the Russians is kindness. The entry for доброта (kindness) in the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language states “abstract noun to добрый (kind)”, which, in turn, is defined as:

1. Делающий добро другим; благожелательный, отзывчивый, обладающий мягким характером (Doing good for others; benevolent; responsive; having mild character);

2. Хороший, нравственный (Good, wholesome).

The recent experimental data obtained by Leybina and Kashapov expand the idea of kindness as one of the core notions of the Russian character, defining it as a “character trait generated by personal states and qualities, openness to and ability to understand others, which is manifested in external and internal positive actions and behaviors towards others.” (Leybina and Kashapov, 2022: 77).

It can be seen from these definitions that доброта (kindness) is defined through two notions found in Top-10 characteristics in Tables 2, 3, and 5 – доброжелательность (benevolence) (as благожелательный,добро is equivalent to благо) and отзывчивость (responsiveness).

In the dictionary entitled Core Values of the Bearers of Russian Culture[3], many of the co-occurrences in the thesaurus of доброта (kindness), including the notion itself (frequency: 37), are combined under the entry Внимание к людям (attention towards people) as an excerpt from the Russian Associative Dictionary. Though not found in the corpus, the Russian characteristic of отзывчивость (responsiveness) mentioned in the Core Values dictionary and by the respondents of the questionnaire-based study can be considered as one of the fundamental constituents of the notion доброта (kindness). Thus, based on the combined data from the sources analyzed we can conclude that доброта (kindness) for Russians is comprised of сострадание (compassion), милосердие (mercy), and отзывчивость (responsiveness).

Our findings are supported by the results of the recent experimental research by Leybina and Kashapov (Leybina and Kashapov, 2022) that showed that kind behavior of Russians generally falls into six categories, including 1. Polite/respectful actions; 2. Generous actions; 3. Acts of forgiveness; 4. Help (including rescue); 5. Pleasing actions; and 6. Altruistic sacrifice.

The WordSketch for доброта (kindness) demonstrates that the adjectives that describe this noun are primarily related to the degree of kindness, as in безграничная доброта (unrestrained kindness), безмерная доброта (immeasurable kindness), беспредельная доброта (infinite kindness), неисчерпаемая доброта (inexhaustible kindness). Of note is that these adjectives, despite their qualitative nature, describe доброта (kindness) as a value that cannot be measured, limited, or exhausted. The second group of adjectives describes bearers of доброта (kindness) or its imaginary location: человеческая доброта (human kindness), ангельская доброта (angelic kindness), душевная доброта/сердечная доброта (kindness of heart/soul).

Two notions from the Russian corpus data, трудолюбие (industriousness) and терпение (patience), have indirect relation to доброта (kindness). In the Russian mindset, kindness, patience, and industriousness are considered as the virtues of a decent person.

Keyword in context analysis

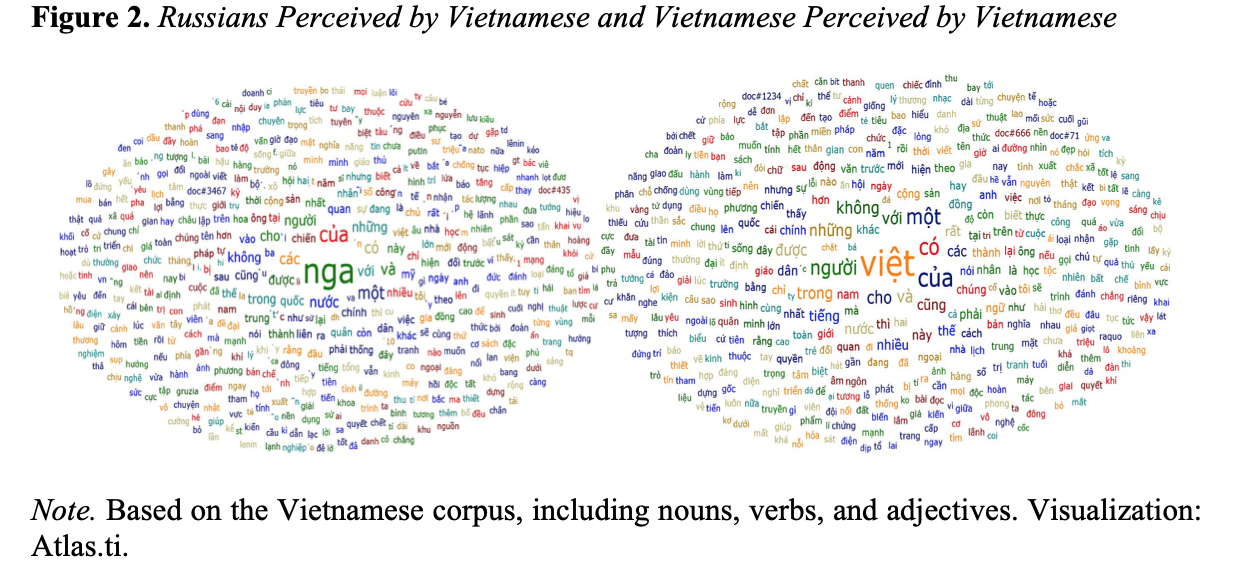

The corpus linguistic analysis of the data of the previous research was complemented by a purely corpus-based additional research, whereas a randomized sample of 1000 contexts of the words Vietnamese (вьетнамский, Việt) and Russian (русский, Nga) were investigated. This confirmed that war as a central topic is present in the Top-10 nouns of these corpora, with the word form война (war) and chiến tranh (war) in the respective collections of texts. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the abovementioned four created linguistic corpora by displaying the most relevant lexemes in the noun, adjective and verb word classes.

Figure 1. Vietnamese Perceived by Russians and Russians Perceived by Russians

Note. Based on the Russian corpus, including nouns, verbs, and adjectives. Visualization: Atlas.ti.

Figure 2. Russians Perceived by Vietnamese and Vietnamese Perceived by Vietnamese

Note. Based on the Vietnamese corpus, including nouns, verbs, and adjectives. Visualization: Atlas.ti.

In accordance with Table 6, presenting frequencies of collocations of the adjective вьетнамский in 1000 randomized contexts, война (war) accounted for the highest frequency in the corpus data. The underlying reason may be that the Vietnamese War ended less than 50 years ago, thus the term is frequently mentioned in the texts included in the corpus. Further to that, in the period between 1858 and 1975, Vietnam witnessed and participated in numerous wars. The word war, therefore, is often mentioned when Vietnam is the topic of the discourse. Similarly, in the Vietnamese data set, chiến (tranh) (war) is the sixth most frequent noun with a frequency value 163. The exact word occurrence in the Vietnamese data set is chiến that is only the first lexical unit (morpheme-like element) of the noun chiến (tranh) (war).

Based on the frequency of the respective collocations it can be assumed that the Russian self-perception is strongly characterized by a respect to the past, crystallized in lexemes including история (history) and исторический (historical). Language (язык) and culture (культура) are integral parts of the Russian self-perception as well, культура (culture) appearing as the ninth most frequent noun in the respective subcorpus. Judging by the respective subcorpus data, Vietnamese perceive themselves as closely associated with people/nation (người, dân), country (nước, quốc), and soil (đất), as well as with language (tiếng) and house/home (nhà). They also perceive themselves as great (đại, lớn) and equal (bằng), which appear in the Top-10 most frequent adjectives of the subcorpus.

An interesting phenomenon of the Vietnamese perception of Russians is associated with characteristics connected to Russians’ physical appearance marked by words great (lớn), tall (cao), and strong (mạnh). The United States appears in both Russians’ perception of Vietnamese and Vietnamese’s perception of Russians in lexemes США (USA), американский (American), and mỹ (American). Vietnamese cuisine is a strong part of how Russians perceive the Vietnamese people marked by such nouns as кухня (cuisine) and ресторан (restaurant).

It is important to note that some of the lexical units displayed in the Vietnamese data tables cannot be considered as lexemes – but show characteristics of morphemes, rather – and they do not have a full, independent meaning. These morphemes are not applied independently, but usually appear as parts of compound word formations, for example: quốc+gia = quốcgia (country), công+việc = côngviệc (work), chiến+tranh = chiếntranh (war), thời+gian = thờigian (time). This might be considered as a limitation of the present study and the corpus linguistic analysis, as analytical tools generally consider standalone units as words. At the same time, the meaning of these morphemes can be reconstructed based on their context, thus their intended meaning can also be determined.

The obtained results demonstrate that mere finding the similarity and the disparity between the characteristics that are attributed by peoples to themselves or other peoples might lead to premature conclusions about the degree of cultural equivalence. In the present work we hypothesized that there is a culture-specific content behind the words that are commonly understood as equivalents, based on their presence in the bilingual dictionaries. Indeed, corpus linguistic analysis in our research demonstrates that these words should rather be understood as quasi-equivalents, their semantic structure being different due to their culture-specific component.

Conclusions

Based on the results of the preceding research on Russian-Vietnamese mutual and self-perceptions, several common characteristics were identified including the following five pairs of traits: courage (смелость/ dũng cảm); hospitality (гостеприимство/ hiếu khách); industriousness (трудолюбие/ cần cù); intelligence (ум/ thông minh); kindness (доброта/ tốt bụng). Although these pairs of words can be considered as linguistic equivalents from the perspective of translation studies, their semantic structure (both denotation and connotation) might presumably be different. These semantic differences were investigated in this research applying corpus linguistic analytic methods, including: (1) automatic thesauri construction; and (2) a subcorpus linguistic concordance analysis of the context of the words Russian (русский; Nga) and Vietnamese (вьетнамский; Việt), performed on the basis of the two selected reference corpora (Russian language: ruTenTen11; Vietnamese language: VietnameseWaC).

As it was demonstrated, the corpus linguistic approach proved to be an effective tool not only for comparison of the ethnic portraits and self-portraits of the two nations, but also for pinpointing semantic differences between the investigated pairs of traits. The use of automatically generated thesauri allowed us to describe the semantic structure of the investigated characteristics, revealing the culture-specific content that is commonly left unaccounted for.

The results of the secondary investigation and concordance analysis of the developed subcorpora also suggest that this approach is of value for further clarification and the more precise description of the ethnic portraits and self-portraits. Common concordances were identified both in the Russian and the Vietnamese subcorpora, including notions of war (война; chiến), time (время; thời), as well as country (страна; nước, quốc). It is worth mentioning that the respective languages (язык;tiếng, ngôn) are also among the Top-10 most frequent concordances. The Russian subcorpus associates Vietnamese with language, cuisine, and restaurant, whereas in the Vietnamese subcorpus the following high-frequent qualities are encountered: lớn (great), cao (tall), mạnh (strong).

It can be concluded that the combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches provides a more comprehensive picture of how the processes of formation of ethnic portraits and self-portraits are reflected in languages and cultures. After additional semantic analysis, the unique linguistic data obtained can provide invaluable information about the ethnic portraits and self-portraits of the two peoples. The current study opens up the door for future research into the culture-specific components of the quasi-equivalent words in different languages and cultures, suggesting the possible universal approach to comprehensive reconstruction of ethnic portraits and self-portraits.

[1] ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH [ATLAS.ti 22 Windows] (2022). Available at: https://atlasti.com (Accessed 1 May 2023).

[2] Ushakov, D. N. (ed.) (2013). Tolkovyj slovar' russkogo yazyka [Dictionary of the Russian Language]. Four volumes. 1935–1940, State Publishing House of Foreign and National Dictionaries. (In Russian)

[3] Vashunina, I. V., Dronov, V. V., Ilyina, V. A., Makhovikov, D. V., Nistratov, A. A., Nistratova, S. L. and Tarasov, E. F. (2019). Core values of the bearers of Russian culture, Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Thanks

The reported study was funded by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) and the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences (VASS), project number 21-512-92001\22.

Reference lists

Adler, N. J. (1993). Competitive Frontiers, International Studies of Management & Organization, 23 (2), 3–23. (In English)

Baker, C. (2014). Stereotyping and women's roles in leadership positions, Industrial and Commercial Training, 46 (6), 332–337. (In English)

Duy, N. T. T. (2021). Educating Students on Traditional Cultural Values of Vietnamese People, South Asian Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3 (5), 309–314. (In English)

Endres, K. W. (2015). Constructing the Neighbourly “Other”: Trade Relations and Mutual Perceptions across the Vietnam–China Border, Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 30 (3), 710–741. (In English)

Gablasova, D., Brezina, V. and McEnery, T. (2017). Collocations in corpus-based language learning research: Identifying, comparing, and interpreting the evidence, Language Learning, 67 (S1), 155–179. (In English)

Ge, Y. (2022). The linguocultural concept based on word frequency: correlation, differentiation, and cross-cultural comparison, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 47 (1), 3–17. (In English)

Houghton, S. A, Lebedko, M. and Li, S. (2013). Comparing Stereotypes of Chinese Japanese and Russian People: Mutual Perceptions of Students from Neighbouring Countries, in Houghton, S. A, Furumura, Y., Lebedko, M. and Li, S. (eds.), Critical Cultural Awareness: Managing Stereotypes through Intercultural (Language) Education, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 62-85. (In English)

Hunston, S. (2022). Corpora in applied linguistics, Cambridge University Press, UK. (In English)

Jisi, W., Sun, Y., Lu, N., Guo, C., Li, F., Jiao, J. and Xu, B. (2020). Summary of survey report on mutual perceptions between China and the United States, China International Strategy Review, 2, 24–35. (In English)

Jones, C. and Waller, D. (2015). Corpus linguistics for grammar: A guide for research, Routledge, Abingdon, UK. (In English)

Kilgarriff, A, Rychly, P, Smrz, P. and Tugwell, D. (2004). Itri-04-08 the SketchEngine, Proceedings of Euralex, Lorient, France, 105–116. (In English)

Laruelle, M. (2021). Russia and Central Asia: Evolving mutual perceptions and the rise of postcolonial perspectives, in Isaacs, R. and Marat, E. (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Central Asia, Routledge, Abingdon, UK. (In English)

Leonard, S. P., Ufimtseva, N. V. and Markovina, I. Yu. (2019). Language, consciousness and culture: some suggestions to develop further the Moscow school of psycholinguistics, Language and culture, 47, 111–130. (In English)

Leontiev, A. A. (1993). Jazikovoje soznanie i obraz mira [Language consciousness and the image of the world], in Vasilevich, A. P., Zimnyaya, I. A., Leontiev, A. A. (eds.), Yazyk i soznanie: Paradoksalnaya ratsionalnost [Language and consciousness: Paradoxical rationality], Institute of Linguistics, Moscow, Russia, 16–21. (In Russian)

Leybina, A. V. and Kashapov, M. M. (2022). Understanding Kindness in the Russian Context, Psychology in Russia. State of the Art, 15 (1), 66–82. (In English)

Markovina, I., Lenart, I., Matyushin, A. and Pham, H. (2022). Russian-Vietnamese mutual perceptions from linguistic and cultural perspectives, Heliyon, 8 (6), e09763. (In English)

Markovina, I. Yu., Matyushin, A. A., Lenart, I. and Pham, H. (2021). Perception of Russians and Vietnamese by Russian respondents: an experimental study, Journal of Psycholinguistics, 2 (48), 74–85. (In Russian)

Markovina, I. Y., Matyushin, A. A. and Lenart, I. (2023). HOSPITALITY FROM THE RUSSIAN AND VIETNAMESE PERSPECTIVES: WEB CORPORA ANALYSIS, Synergy of Languages & Cultures 2022: Interdiscipilinary Studies, 316-322. https://doi.org/10.21638/2782-1943.2022.26(In English)

McEnery, T. and Hardie, A. (2011). Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Mollov, B. and Lavie, Ch. (2016). The Impact of Jewish-Arab Intercultural Encounters and the Discourse of the Holocaust on Mutual Perceptions, in Pandey, K. (ed.), Promoting Global Peace and Civic Engagement through Education, IGI Global, Hershey, USA. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.913736(In English)

Moon, R. (2010). What can a corpus tell us about lexis?, in McCarthy, M. and O'Keeffe, A. (eds.), The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics, Routledge, Abingdon, UK, 197–211. (In English)

Muratbekova-Touron, M. (2011). Mutual perception of Russian and French managers, TheInternational Journal of Human Resource Management, 22 (8), 1723–1740. (In English)

Nguyen, C. H. (2021). Vietnamese Students' Perceptions of Moral Values: An Assessment by Students at An Giang University, Universal Journal of Educational Research, 9 (11), 1814–1825. (In English)

Oelsner, A. (2003). Two Sides of the Same Coin: Mutual Perceptions and Security Community in the Case of Argentina and Brazil, in Laursen, F. (ed.), Comparative Regional Integration. Routledge, UK. (In English)

Prokohorov, Yu. E. and Sternin, I. A. (2006). Russians: communicative behavior, Flinta, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Rebechi, R. R. (2013). Corpus-driven Methodology for Exploring Cultural References in the Areas of Cooking, Football and Hotel Industry, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 95, 336–343. (In English)

Rychlý, P. (2008). A lexicographer-friendly association score, in Sojka, P. and Horák, A. (eds.), Proceedings of recent advances in Slavonic natural language processing, RASLAN Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia, 6–9. (In English)

Rozumko, A. (2012). Cross-cultural aspects of contrastive studies: the discourse of fact and truth in English and Polish. A corpus-based study, in Rozumko, A. (ed.), Directions in English-Polish Contrastive Research, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku, Białystok, Poland. (In English)

Saaler, S., Kudo, A. and Tajima, N. (2017). Mutual Perceptions and Images in Japanese-German Relations, 1860-2010, in Brill's Japanese Studies Library, Vol. 59. Brill. Leiden, Netherlands. (In English)

Seo, E. H. and Lee, J. (2019). The Study of Koreans’ Perception about Vietnam using Social Big Data, The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 19 (3), 1–9. (In English)

Sorokin, Y. A. (1994). Ethnic conflictology, Russian Lyceum, Samara, Russia. (In Russian)

Stewart, R., Wright, B., Smith, L., Roberts, S. and Russel, N. (2021). Gendered stereotypes and norms: a systematic review of interventions designed to shift attitudes and behavior, Heliyon, 7 (4), e06660. (In English)

Stubbs, M. (1996). Text and corpus analysis, Blackwell, Oxford, UK. (In English)

Stubbs, M. (2006). Corpus analysis: the state of the art and three types of unanswered questions, in Geoff Thompson, in Hunston, S. (ed.), System and Corpus: Exploring Connections, Equinox, London, UK, 15–36. (In English)

Tarasov, Y. F. (1996). Jazikovoje soznanije – perespektivi issledovanija [Language consciousness – research perspectives], Etnokulturnaja spetsifika yazykovogo soznaniya [The ethnocultural specificity of language consciousness], Institute of Linguistics, Moscow, Russia, 7–22. (In Russian)

Tho, N. N. (2016). Confucianism and humane education in contemporary Vietnam, International Communication of Chinese Culture, 3 (4), 645–671. (In English)

Thu, T. N. M., Thi, T. D. V., Thuy, N. T. and Huy, D. T. N. (2021). Confucianism Theories and Its Influence on Vietnam Society, Ilkogretim Online, 20 (4), 1434–1437. (In English)

Tognini-Bonelli, E. (2001). Corpus Linguistics at Work, John Benjamins Publishing. Amsterdam/Philadelphia. (In English)

Ufimtseva, N. V. (1996). Russkije: Opit estche odnogo samopoznanija [The Russians: An attempt at one more self-knowledge], Etnokulturnaya spetsifika yazykovogo soznaniya [The ethnocultural specificity of language consciousness], Institute of Linguistics, Moscow, Russia, 139–162. (In Russian)

Vaičenonienė, J. (2001). Using corpora to obtain social and cultural information: A case study of America, Kalbų Studijos, 1, 6–9. (In English)