Linguistic profiling of text genres: adventure stories vs. textbooks

Abstract

In this article we test the hypothesis that genre-inherent quantitative linguistic parameters can be reduced to a list of few provided with strictly defined ranges of value. The current research as part of a large project is aimed at contrastive analysis of textbooks on History and Social Studies, and adventure stories. Using RuLingva[1], we identified 18 genre variables, computed their frequencies and employed the Kruskal-Wallis H Test to evaluate the differences significance. The results suggest that the list of the most indicative parameters include sentence length, noun genitive case, future tense, ratio of verbs to nouns, provisionally called ‘narrativity’, and frequency. All the identified parameters have statistically significant differences and three of them (sentence length, genitive noun, and “narrativity”) are implemented in non-overlapping “genre-inherent” ranges of values attributed to (a) History and Social studies textbooks and (b) adventure stories. With the view that the target audience of adventure stories are not expected to demonstrate high levels of professional training but logical skills, we argue that the relatively stable readability of adventure stories, i.e. FKGL = 8-9, can also be attributed to the genre-inherent characteristics. Our results certify that incorporating text complexity indices improve the classification performance of genre quantitative analysis. We also offer our views on linguistic and statistical aspects of the proposed approach for future studies. Further research is needed to see how the same parameters are exploited in texts of other genres and subject domains.

Keywords: Linguistic Profiling, Textbook analysis, Adventure Stories, Russian language, Genres, RuLingva, Parametrisation indices, Classification Models

1. Introduction

The field of text complexity research in Russia has shown remarkable growth and the rise of new research directions in recent years, but linguistic profiling has received much less attention. The latter is especially true for Russian texts: genre analysis is widely used to study a variety of English academic genres (Swales, 2004), while Russian-oriented research is still considered a research niche (Mendhakar, 2022). Text parameterization as identification of the reference ranges of value of a limited number of parameters used to discriminate text genres (or types) proves to be in great demand in natural language processing (NLP) and is based on statistical methods that allow the identification and analysis of the main characteristics of text, which is crucial for text classification and comprehension (Manning and Schütze, 1999). Modern-day NLP algorithms are based on (1) highly sophisticated IT tools with their astonishing processing abilities enabling to concurrently process both, the content and form of the text and (2) availability of ever-growing language corpora.

These algorithms have been successfully used to identify linguistic variables specific for a certain text type (Koppel et al., 2002) as well as in training machine learning algorithms and building classifying models for a given pragmatic or linguistic task. When employed with statistical methods, the latter can solve numerous core linguistic problems including forensic applications, language of the elderly or social classes, language acquisition and evaluating complexity of textbooks. One of the many such classical problems is text/genre profiling, i.e. identifying text patterns which can be used to classify text genres or types (Halteren, 2004; Paltridge, 1994). The tradition in the classical genre-metric approaches is to identify both, the most salient and the rarest feature(s) in a text (Dell’Orletta et al., 2013) placing a special emphasis on revealing patterns in the smallest possible segments of text (Montemagni, 2013).

Focusing on cross-genre comparison, in this study we briefly outline foundations of the modern paradigm of linguistic profiling, within which parameterization is viewed as a key to genre profiling, objective assessment of text linguistic complexity and cognitive difficulty. We test the hypothesis that genre-inherent quantitative linguistic parameters can be reduced to a list of few and provided with strictly defined value ranges.

The Research Questions of the study are as follows:

1) What are the most indicative parameters able to discriminate (a) History and Social Studies textbooks from (b) adventure stories?

2) What are the “genre-attributed” ranges of variables for (a) History textbooks, (b) Social Studies textbooks and (c) Adventure Stories?

Our research objective is to design and validate classification parametric models of Russian textbooks on two area domains, i.e. History and Social Studies, on the one hand, and adventure stories, on the other. We focus on identifying the list of the most genre indicative parameters of (a) History textbooks; (b) Social Studies textbooks; (c) adventure stories as well as “genre-attributed” ranges of variables for (a) History textbooks, (b) Social Studies textbooks and (c) Adventure Stories.

2. Literature review

2.1. Multi-dimensional method

Since 1986 when D. Biber first (1) announced text type (or genre) profiling as a function of text parameterization (Biber, 1986) and later (2) developed foundations of the multi-dimensional method for genre variation (Biber, 1988), numerous researchers focused on text profiling for different pragmatic and linguistic purposes (Mendhakar, 2022). Being quantitative in nature, the multi-dimensional method received a positive impetus of computational linguistics, and its modern version implies identifying genre specific indices, enabling to classify text types and genres with the help of a limited number of linguistic parameters.

2.2. The Adventure Story as a Genre

Defining adventure as a genre M. M. Bakhtin argues that it changes the real flow of time, compresses it: the time moves faster, almost without changing characters; it is divided into a number of short segments (adventures) (Bakhtin, 1975). A. Vulis as M. M. Bakhtin’s follower highlights its attributive features: “Adventure is a plot hyperbole that exaggerates obstacles on the human path – quantitatively (their number, concentration, scale) and qualitatively (the intervention of chance and miracle, regulation of life by the law of coincidences)" (Vulis, 1986). Ian McGuire defines adventure as the movement from safety to danger then back again and admits that this genre often overlaps with crime novels, sea stories, Robinsonades, spy stories, science fiction and fantasy[1].

The initial impetus for the development of adventure as a genre in the USSR was the call of N. I. Bukharin at the Fifth Congress of the RCYU in October 1922, who proposed the idea of diverting young people from reading bourgeois literature by creating writings about "communist Pinkertons" (Malikova, 2006). Bukharin proposed to write various revolutionary novels using plots from military actions, adventures during underground activities, events of the civil war and activities of the Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution and Sabotage.[2] Over the period from the 1920-s to the early 1990-s, the USSR published numerous adventure books with pirates, musketeers, Indians, ocean explorers, and spies as the main characters (Dralyuk, 2011). The Soviet adventure story is a story about danger and risks to the country and about the rewards of living with other people. True and deep adventures transform the characters in such a way that the old ways of thinking and living are no longer possible. Adventure stories, gripping and full of incident, are targeted for young people, who though not personally involved in revolutions and wars are expected to be educated on the romanticized past of the country. Employing techniques of narration and storytelling, adventure turns unglamorous work of agriculture or electrification into heroic and patriotic, its positive heroes “provide models of courage and steadfastness, and are therefore seen to play an important role in the political acculturation of young people and the instillation of patriotic values” (Brine, 1986). Presenting Soviet literature Richard Stites argues that “Socialist realism gave the public part of what it wanted: “realism”, adventure, and moral guidance” (Stites, 1992).

2.3. The Textbook as a Genre

Textbook as a genre is expected to “signify the world from a particular perspective and constitute certain modes of social interaction” (Klerides, 2010). Presenting different perceptions of readership and authorship embedded in a textbook, experts argue that the new type of History textbooks as a genre “encodes different views about the writer’s task and the science of history. Unlike the traditional genre, the focus here is on the promotion of historical thinking” (Klerides, 2010). Students are expected to develop skills of ‘empathetic reading’ and study historical events from multiple perspectives. Recommending to teach “how” rather than “what”, J. Slater argues that History teaching is expected to be “mind-opening”, its methods are inquiry, and the sources are multiple (Slater, 1989: 16). One of the History textbooks we use to illustrate the discourse of modern Russian domain was published in 2016 and it is still recommended by the Ministry of Education of RF as a part of the Federal List of Textbooks[3] . The passage below is excerpted from chapter 22 about the Home Politics of Alexander III, it is accompanied by a range of verbal and visual sources, including reproduction of paintings and appears under the heading “Questions and Tasks to Chapter”.

1. Tell us about Alexander III’s views on governing the country. Who became the inspirer and conductor of his domestic policy? 2. What do you understand the term “counter-reforms” and why? 3. What opportunities did the introduction of a state of emergency in the provinces give to the authorities? 4. Who elected the zemstvo leaders? What interests did they represent? 5. What was the policy of Alexander III in education and press? List the main legislative acts. Who are “cook’s children”? 6. How did Alexander III’s policy of trusteeship towards the peasants manifest itself? (Arsentiev et al., 2016: 9).

As the textbook authors are focused on developing skills of historical thinking and promoting different views, readers are provided with numerous sources of different origin and the discourse incorporates mostly active constructions (active voice, Past simple). Readers are not offered judgmental biases or prescriptive statements about what they ought to do, since there is a higher degree of “narrativity” than “descriptiveness” (See Table 3).

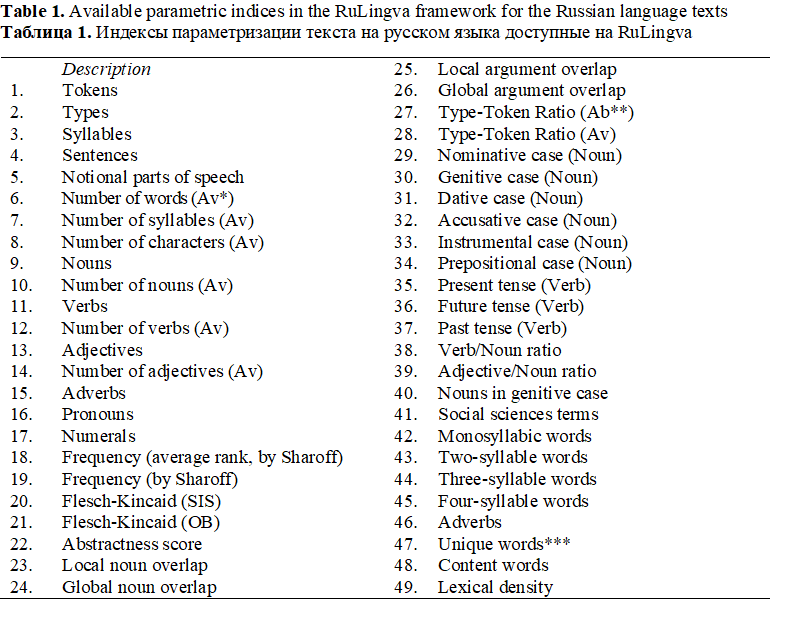

2.4. RuLingva Textual Indices

RuLingva[4] provides 49 indices for the Russian language including descriptive, morphological, lexical, and discourse (cohesion) indices, as presented in Table 1 below. Text pre-processing with RiLingva, including POS tagging, and named entity recognition, relies either on Natasha or SpaCy, as part of the github library[5].

Descriptive indices include the number of sentences, words, and syllables per document. RuLingva also performs morphological measurements ascribed to each word in the text to parameterize morphological categories of a text including part-of-speech (POS) tagging, cases for nouns, tenses for verbs, ratios of different notional parts of speech per sentence and text, etc. Lexical indices provide information about words frequency, abstractness, their length, lexical density and diversity. Discourse constituents in text parameterization are local and global noun overlaps and argument overlaps. These cohesion categories “support” readers in establishing a coherent understanding of the text and constructing a mental model of the corresponding referential situation

(Medvedev et al., 2022).

(Medvedev et al., 2022).

Table 1. Available parametric indices in the RuLingva framework for the Russian language texts

Таблица 1. Индексы параметризации текста на русском языка доступные на RuLingva

*Av stands for average, **Ab marks absolute

***Unique words are words used ONCE in the analyzed document

3. Method

3.1. Textbooks and Adventure Story Corpus

This study utilizes the corpus compiled and elaborated by the experts of the Text Analytics Laboratory, Institute of Philology and Intercultural Communication, Kazan. The dataset consists of two subcorpora: I. Textbooks collection consists of 11 Russian textbooks distributed across two school grade levels, 8th and 9th, and two subjects, i.e. History and Social Studies; II. Russian children’s adventure stories published in the Soviet times, i.e. from the late 1920-s to the early 1990-s.

The authors of the adventure stories selected for the research did not rank among the leading names of the Soviet literature: by the standards of the period, they were ordinary, but we believe that nations’ history is better read through the books its writers created for children (Husband, 2006). As for readability of adventure stories, as a genre of mass literature they are expected to be easy and simple to comprehend, addressed to a reader who requires neither a special literary, artistic taste, or special education.

The choice of the subjects and the grade levels of the textbooks, i.e. 8 and 9, was not made randomly but to balance the thematic and historical profiles of the adventure stories and the textbooks. History textbooks of 8th and 9th grades highlight the history of our country of two centuries, 19th and 20th with the focus on the October revolution, civil war, two World Wars, formation, development and collapse of the USSR. Textbooks on Social Studies, on the other hand, develop ideas on social relations and their patterns, processes of social development, etc.

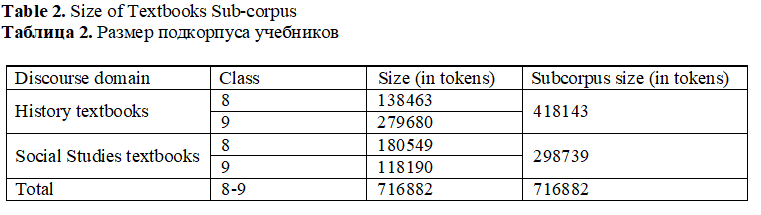

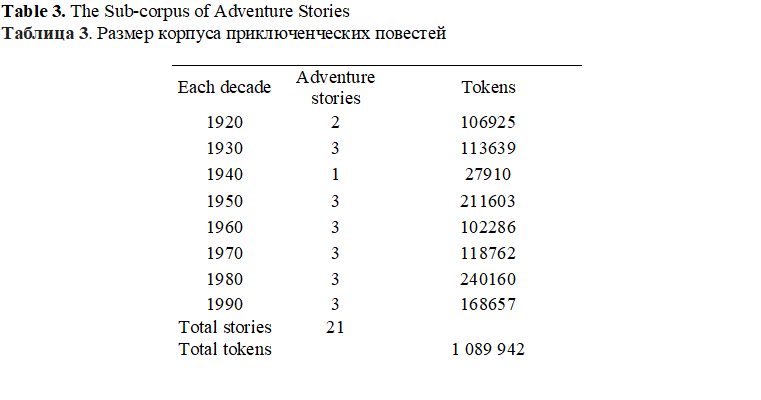

Table 2 and 3 below show that the corpus is nearly evenly divided across the textbooks and adventure stories.

Table 2. Size of Textbooks Sub-corpus

Таблица 2. Размер подкорпуса учебников

Table 3. The Sub-corpus of Adventure Stories

Таблица 3. Размер корпуса приключенческих повестей

While preparing the dataset for developing classification models we aimed at increasing the number of documents in the corpus and limited the input passages length to about 1000 tokens. Since the average number of tokens per story or textbook far exceeds this limit (see Tables 2, 3), after segmenting each document into pieces of about 1000 tokens we deleted the rest of the text thus imperceptibly reducing the size of the Corpus.

3.2. Research Design

The research design comprised four stages:

On Stage I, Preparatory, we pre-processed the research corpus composed of 21 adventure stories, 5 History textbooks and 6 Social Studies textbooks. To ensure the discourse consistency, we deleted meta-descriptions, prefaces, author’s introductions, contents, illustrations, inscriptions, figure captions, notes, self-test questions, laboratory assignments, chapter titles, subheadings, footers, etc.

On Stage II, each book was segmented into nearly equal parts of about 1000 tokens: as we segmented texts at the end of a sentence only, never cutting a sentence, the minimum text size in the collection is 957 tokens, and the maximum – 1031 tokens. Since the last section of a text usually contained significantly fewer than 1000 tokens, it was not used for further research. The total size of the research corpus was 1,806,824 tokens (Table 2, 3) or 1804 texts; each with the size of about 1000 tokens.

On Stage III, we computed values of each text with the framework of RuLingva[6], an automatic analyzer of Russian texts.

On Stage IV, analytical, we processed RuLingva data using STATISTICA software and assessed statistically significant differences between three genres: adventure stories, History textbooks, and Social Studies textbooks. The differences were evaluated with the help of the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H test (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952).

4. Analysis

4.1. RuLingva Feature Selection

We computed the textual indices for each of 1804 texts using RuLingva framework.

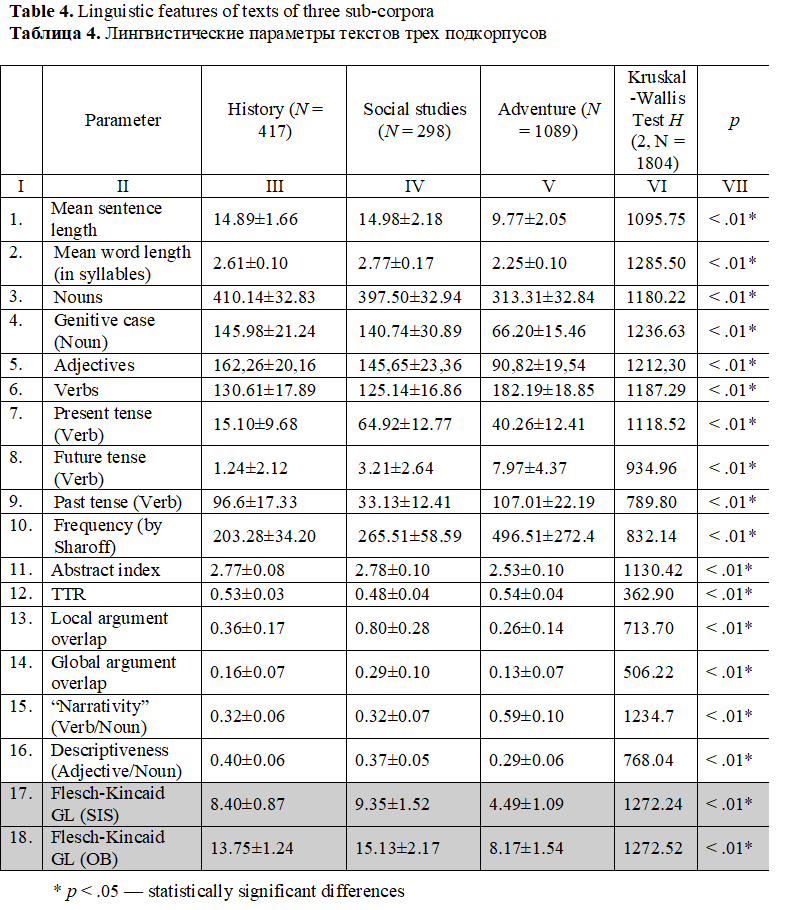

Table 4. Linguistic features of texts of three sub-corpora

Таблица 4. Лингвистические параметры текстов трех подкорпусов

* p < .05 — statistically significant differences

Table 4 presents means and standard deviations of the linguistic parameters under the analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis H test (column p) confirms that the three genres, i.e. History textbooks, Social Studies textbooks and Adventure stories, have statistically significant differences in the parameters in Table 3.

We should separately mention parameters 17 and 18 in Table 4, i.e. Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (SIS) and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (OB). As readability formulas are genre-dependent, we assessed readability of textbooks and adventure stories with two versions of adopted for the Russian language Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formulas: we implemented FKGL (SIS) (line 17) for textbooks and computed readability of adventure stories with FKGL (OB) (line 18). FKGL (OB) was derived based on fiction and as such is not supposed to be applied to compute readability of textbooks.

The findings suggest that textbooks (FKGL=8.40±0.87) and adventure stories (FKGL=8.17±1.54) are addressed to the same target audience, i.e. readers with eight years of formal schooling (Gatiyatullina et al., 2020).

4.2. Classification Models

In this study we mostly employ the multi-dimensional method for genre variation and focus on two types of oppositions: (I) textbook as a genre vs an adventure story as a genre and (II) History Textbooks vs Social Studies Textbooks vs Adventure stories (see 17 parameters offered in Table 4).

Figure 1. a) Mean sentence length (in words); b) Mean word length (in syllables)

Рисунок 1. а) Средняя длина предложения (в словах); b) Средняя длина слов (в слогах)

A comparison of the average sentence length and the average number of syllables in textbooks and adventure stories shows the difference between these genres. Fiction texts have shorter sentences and shorter words (see Figure 1).

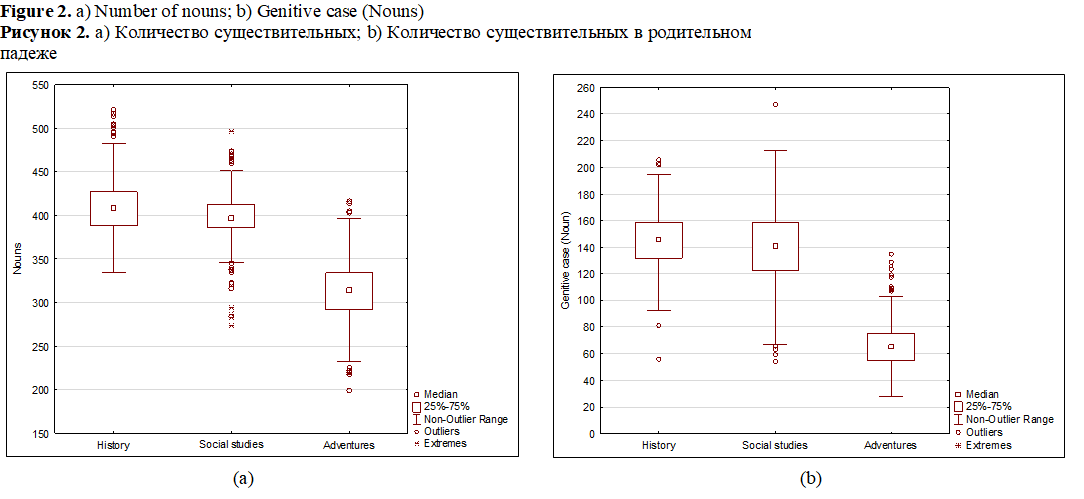

Figure 2. a) Number of nouns; b) Genitive case (Nouns)

Рисунок 2. а) Количество существительных; b) Количество существительных в родительном падеже

The syntactic structures of sentences in the texts have significant differences: nominalization in the textbook texts is significantly higher than that in adventure stories. Moreover, the share of nouns in the genitive case in textbook texts is also higher, i.e. it makes up to 35% while in adventure stories it is as low as 21% (see Figure 2).

Figure 3. Frequency (as per Sharoff’s); b) Number of adjectives

Рисунок 3. Частотность по словарю Шаровa; b) Количество прилагательных

Vocabulary frequency analysis reveals a wider range of the metric in adventure stories than in the textbooks of both subject domains: textbooks are more homogeneous and their average vocabulary frequency is lower, which is apparently caused by incidence of scientific vocabulary. The number of adjectives in textbooks exceeds the number of adjectives in adventure stories (Figure 3-b).

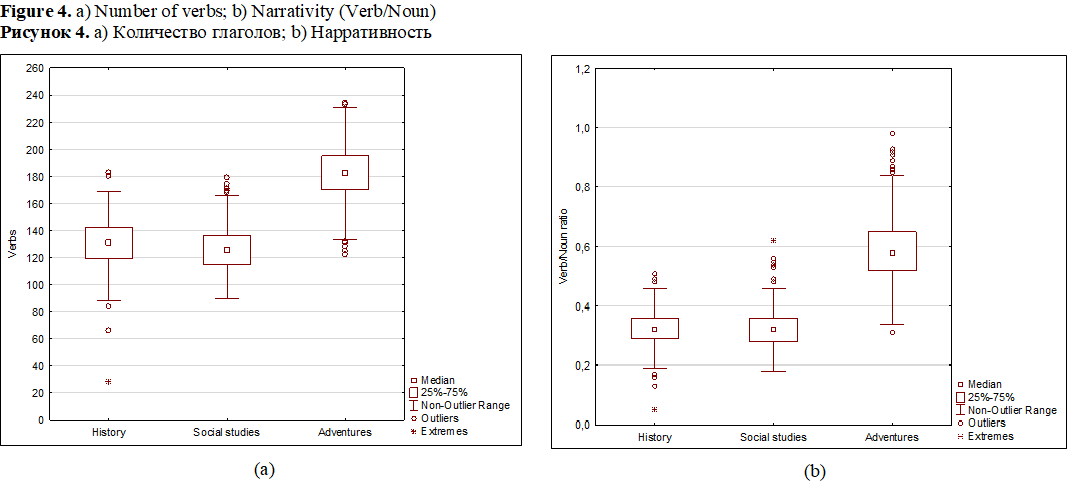

Figure 4. a) Number of verbs; b) Narrativity (Verb/Noun)

Рисунок 4. а) Количество глаголов; b) Нарративность

As adventure stories narrate of active actions of its heroes, the use of verbs is more intensive than in textbooks (see Figure 4).

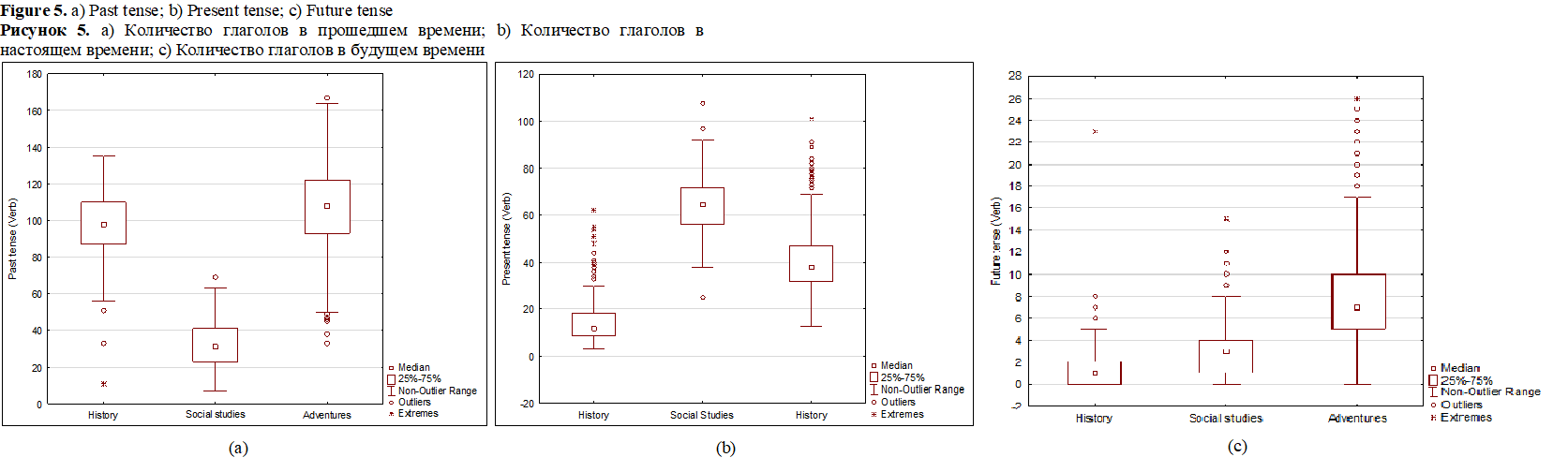

Figure5. a) Past tense; b) Present tense; с) Future tense

Рисунок 5. а) Количество глаголов в прошедшем времени; b) Количество глаголов в настоящем времени; с) Количество глаголов в будущем времени

Contrasting the three sub-genres in each of the verb forms, i.e. past, present and future (see Figure 5), reveals significant differences. The past forms (see Figure 5-a) behave similarly in Adventure stories and History textbooks, while Social Studies textbooks employ fewer past verb forms than the other two genres. Social studies texts are rich in present forms (see Figure 5-b), which can be explained by the specifics of the area: they are expected to provide rules and state of affairs. History textbooks, on the opposite, focus on the past and as such incorporate the lowest ratio of the future forms. The ratio of the future forms is higher in adventure stories. The important thing about the adventure stories is also that they are less homogeneous than textbooks in this matter (see Figure 5-c).

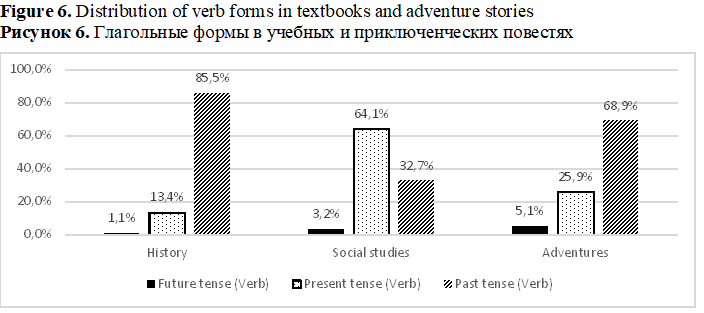

Figure 6 compares the verb forms in each of the three sub-genres separately. The bar chart illustrates that adventure stories and history texts focus predominantly on the past, but the present tense prevails in the social studies texts. As for the adventure stories, though they mostly shed light on the past events, their share of future verbs is higher than in textbooks.

Figure 6. Distribution of verb forms in textbooks and adventure stories

Рисунок 6. Глагольные формы в учебных и приключенческих повестях

5. Results

The most notable differences between textbooks and adventure stories are observed in the following.

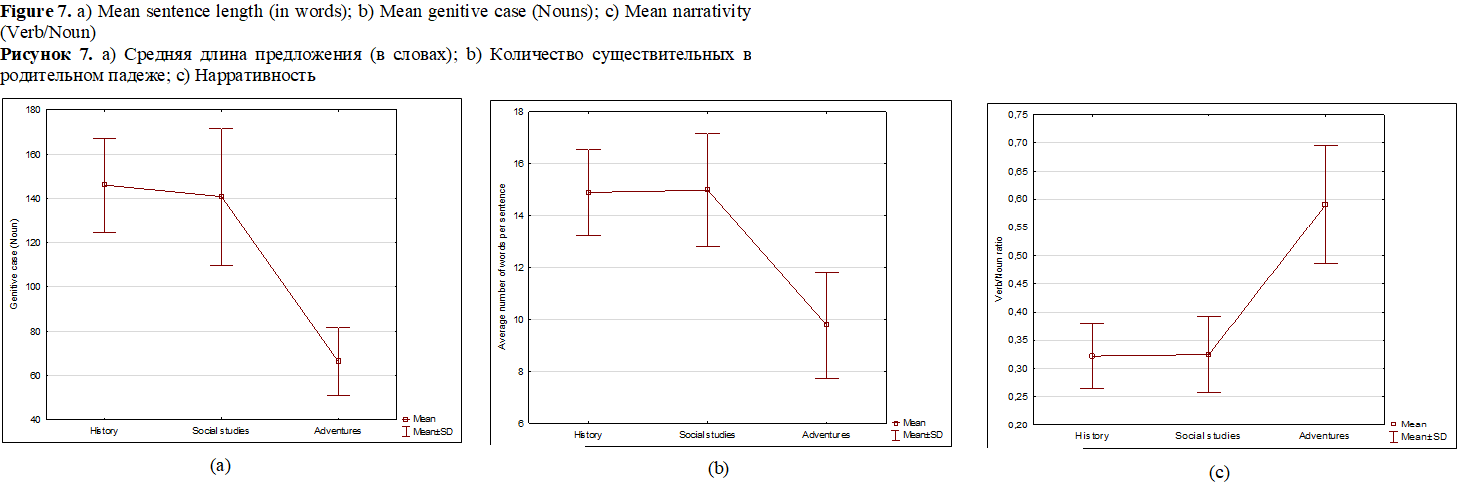

1. Nouns in the Genitive Case. History (145.98±21.24) and Social Studies (140.74±30.89) texts comprise twice as many nouns in the genitive case than adventure stories – 66.20±15.46. Apparently, it is to be viewed as a genre-inherent feature of textbooks.

2. Verbs in the Future Tense discriminate well between texts of the three genres: adventure stories incorporate more verbs in the future tense (7.97±4.37) than Social Studies (3.21±2.64) and History (1.24±2.12) texts. The revealed disparities in variables reach 644% and as such may be employed in genre classification models.

3. Narrativity as the ratio of verbs to nouns in the text is 180% higher in adventure stories (0.59±0.10) than in History (0.32±0.06) and Social Studies (0.32±0.07) textbooks. Similarity of the parameter variables in History and Social Studies texts, i.e. 0.32±0.06 -0.07, suggests a meta-domain level of the parameter enabling foundation for cross-genre classification models.

4. Sentence length in History (14.89±1.66) and Social Studies (14.98±2.18) texts is on average 5 words or 1, 5 times longer than that in adventure stories (9.77±2.05). Similarly to the above it has a potential to serve as a genre classifier.

5. Lexical frequency (as per Sharoff’s) in adventure stories (496.51±272.4) is almost two times higher than in History (203.28±34.20) and Social Studies (265.51±58.59) texts. However, the wide range of its standard deviation in adventure stories indicates the parameter’s heterogeneity and instability: adventure stories incorporate words of both: very high and very low frequencies. The latter may become an object of a new study aimed at defining their shares in the genre vocabulary.

Three of the parameters listed above demonstrate non-overlapping ranges of mean±sd: sentence length (History: 14.89±1.66, Social Studies: 14.98±2.18 and Adventure Stories: 9.77±2.05), Nouns in Genitive Case (History: 145.98±21.24, Social Studies: 140.74±30.89, Adventure Stories: 66.20± 15.46), Narrativity (History: 0.32±0.06, Social Studies: (0.32±0.07, Adventure Stories: 0.59±0.10) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. a) Mean sentence length (in words); b) Mean genitive case (Nouns); с) Mean narrativity (Verb/Noun)

Рисунок 7. а) Средняя длина предложения (в словах); b) Количество существительных в родительном падеже; с) Нарративность

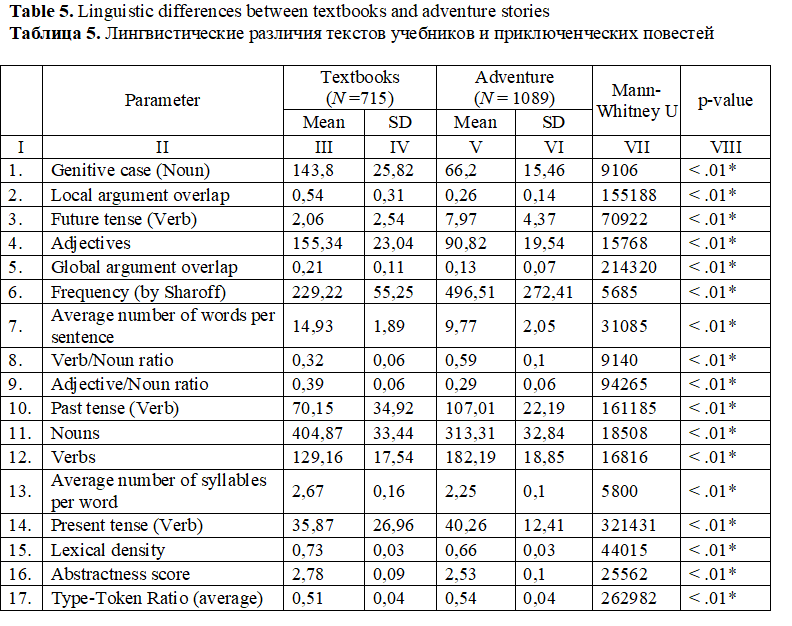

Table 5 below summarizes the list of validated text parameters discriminating textbooks on the one hand and adventure stories on the other. The parameters in the table are ranked and arranged in decreasing order of differences between genres. Statistical analysis showed that all parameters of this table have statistically significant differences.

Table 5. Linguistic differences between textbooks and adventure stories

Таблица 5. Лингвистические различия текстов учебников и приключенческих повестей

With different degrees of probability, each of these parameters or their clusters may be used in genre-classification formulas viewed as a prospect for the current research. The first five parameters in which the greatest differences between genres are observed are Genitive case (Noun), Local argument overlap, Future tense (Verb), Adjectives, Global argument overlap.

6. Discussion

The main findings of this research with respect to adventure stories and textbooks on History and Social Studies are discussed below.

As revealed by the results of the two Research Questions, the differences in genre parameters illustrate different ways of packaging information in fiction and academic texts. Although 15 parameters of 49 computed with RuLingva (see Table 4) indicate genre differences, only five of them demonstrate the most notable differences and are viewed as genre-inherent. The list includes sentence length, noun genitive case, future tense, the ratio of verbs to nouns, provisionally called ‘narrativity’, and frequency. These results confirm that these indices are powerful language markers attributed to textbooks and adventure stories.

We highlight specific characteristics which differ texts of both subject domains (History and Social Studies) from fiction (adventure stories) (see Table 5), thus confirming the idea that various genres and sub-genres have their specific, conventionalized ways of presenting ideas and knowledge (Hyland, 2009).

As previous research indicates, textbooks complexity largely depends on nominalization (Gatiyatullina et al., 2023). In view of the current research results, higher incidence of nouns in the genitive case, which we again confirmed, suggests their function as modifiers and cognitive (informative) complexity of textbooks (Kupriyanov et al., 2023).

Similarly to (Jalilifar et al., 2014), we observe a higher frequency of adjectives in textbooks than in fiction (Table 4): adjectives prevail in textbooks because the authors of academic texts tend to put the focus on objects’ characteristics, rather than human characters and their actions which are expected to be encoded by verbs

The research paradigm in the area implies that lexical density, associated with information density, is higher in more planned and formal texts (Galve, 1998). Our research strongly confirms these assumptions with the joint lexical density of textbooks being 0,73 and that of adventure stories as low as 0,66. Furthermore, information density ultimately tied to disciplinary characteristics reveals in numerous instances of genitive case. The latter is viewed not only as a marker but a tool that the Russian language uses to condense information by modifying nouns (Gatiyatullina et al., 2020).

An unexpected result concerns the ratios of verb forms: we reveal a higher share of future forms in adventure stories than in textbooks, which to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported before.

We also argue that a sample text sufficient to accurately profile texts and classify genres is to be no longer than 1000 tokens (cf. Table 4). As implications of these findings are mostly pragmatic we assume that it may significantly reduce the amount of calculations performed in text parameterization studies.

We believe that the methodology suggested can be used for profiling texts of other genres and languages.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

The article presents results of the primary stage of the research project aimed at identifying genre- inherent parameters of Russian adventure stories and textbooks on History and Social Studies. The preliminary review of the published articles and conference proceedings on the topic elicited a number of research niches in the area.

The study was simultaneously conducted on two sub-corpora of textbooks on History and Social Studies, on the one hand, and adventure stories, on the other. We selected adventure stories and textbooks of similar readability levels, i.e. 8-9 FKGL, assuming the latter to be a fair foundation for text profiling. Reliability of statistical results was achieved by sampling techniques: we segmented the original texts into samples of 1000 tokens. Based on the experience in the area and defining characteristics of the genre we profiled the texts based on the 17 parameters (see Table 4) and registered the highest differences of the following indices: sentence length, noun genitive case, future tense, the ratio of verbs to nouns, provisionally called ‘narrativity’, and frequency.

Computing genre-inherent parameters of fairy-tales and textbooks of other subject domains is viewed by the authors as a near-term perspective of the research. This investigation can also be extended by enquiring into readability levels of adventure novels and new classification models may be designed so as to gain insights into differences between texts of other genres.

Corpus Materials

Textbooks

Arsentiev, N. M., Danilov, A. A., Levandovskiy, A. A. and Tokareva, A. Ja. (2016). Istoriya Rossii. 9 klass. Uchebnik dlya obshheobrazovatelnyh organizatsiy. V 2 ch. [History of Russia. Grade 9. Textbook for secondary schools. In 2 parts], in Torkunov, A. V. (ed.), Prosveshhenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Bogolyubov, L. N. (2010). Obshhestvoznanie. 8 klass: ucheb. dlya obshheobrazovat. uchrezhdeniy [Social Studies. Grade 8. Textbook for secondary schools], in Bogolyubov, L. N. and Gorodetskaya, N. I. (eds.), Prosveshchenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Bogolyubov, L. N., Matveev, A. I. and Zhiltsova, E. I. (2014). Obshhestvoznanie 9 klass: ucheb, dlya obshheobrazovat. organizatsiy [Social Studies. Grade 9. Textbook for secondary schools], in Bogolyubova, L. N. (ed.), Prosveshhenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Danilov, A. A. and Kosulina, L. G. (2015). Istoriya Rossii, XIX vek. 8 klass: ucheb. dlya obshheobrazovat. organizatsiy [History of Russia, XIX century. Grade 8: textbook for secondary schools], Prosveshhenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Judovskaya, A. Ja., Baranov, P. A. and Vanyushkina, L. M. (2023). Istoriya. Vseobshhaya istoriya. Istoriya Novogo vremeni. XVIII vek. 8-i klass. Uchebnik [History. General History. History of the New Time. XVIII century. Grade 8. Textbook], in Iskenderov, A. A. (ed.), Prosveshhenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Judovskaya, A. Ja. and Baranov, P. A. (2019). Vseobshhaya istoriya. Istoriya Novogo vremeni. 9 klass. Uchebnik [General History. History of the New Time. Grade 9. Textbook], in Iskenderov, A. A., Prosveshhenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Kotova, O. A. and Liskova, T. E. (2019). Obshhestvoznanie. 8 klass. Uchebnik [Social Studies. Grade 8. Textbook], Prosveshhenie, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Kravchenko, A. I. (2010). Obshhestvoznanie: Uchebnik dlya 8 klassa obshheobrazovatelnyh uchrezhdeniy [Social Studies: Textbook for the 8th grade of secondary schools], Russkoe slovo, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Lyashenko, L. M., Volobuev, O. V. and Simonova, E. V. (2016). Istoriya Rossii: XIX - nachalo XX v. 9 kl. Uchebnik [History of Russia: XIX - early XX century. Grade 9. Textbook], Drofa, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Nikitin, A. F. and Nikitina, T. I. (2014). Obshhestvoznanie. 8 klass. Uchebnik [Social Studies. Grade 8. Textbook], Drofa, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Nikitin, A. F. and Nikitina, T. I. (2014). Obshhestvoznanie. 9 klass. Uchebnik [Social Studies. Grade 9. Textbook], Drofa, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Adventure Stories

Belyaev, A. R. (1926). Ostrov pogibshih korablei [The Island of Lost Ships], Vsemirny sledopyt, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Bozhatkin, M. I. (1960). Vzryv v bukhte Tikhoy: Povesti i rasskazy [Explosion in Tikhaya Bay: novels and tales], Kn.-gaz. izd-vo, Kherson, URSS, Russia. (In Russian)

Borshhagovskiy, A. M. (1984). Trevozhnye oblaka [Unsettling clouds], Fizkultura i sport, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Cherkashin, N. A. (1991). Son «Svyatogo Petra» [The dream of "St. Peter"], Molodaya gvardiya, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Chukovskiy, N. K. (1925). Tantaliena [Tantalena], Raduga, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Davydov, Ju. V. (1959). Kapitany ishhut put [The captains are looking for a way], Detskaya literatura, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Gagarin, S. S. (1990). Delo o Bermudskom treugolnike [The Bermuda Triangle case], SP “Interprint”, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Kapitsa, P. I. (1956). V otkrytom more [On the high seas], Detgiz, Leningrad, Russia. (In Russian)

Khaliletskiy, G. G. (1955). Avrora ukhodit v boy [The Aurora is going into battle], Primorskoe kn.izd-vo, Vladivostok, Russia. (In Russian)

Knyazev, L. N. (1990). Sataninskiy reis [The Satanic Voyage], SP “Interprint”, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Korzhikov, V. T. and Valk, G. O. (1981). Volny slovno kenguru. Povesti o dalekih plavaniyah [Waves like kangaroos. Stories of distant sailing], Detskaya literatura, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Lebedenko, A. G. (1930). Vosstanie na «Sv. Anne» [Rebellion on St Anne's], Gos. izd-vo, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Lagin, L. I. (1946). Bronenosets «Anyuta» [Battleship "Anyuta"], Detgiz, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Paustovskiy, K. G. (1932). Kara-Bugaz [Kara-Bugaz], Ogiz-Detgiz, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Plotnikov, A. N. (1973). Molchalivoe more [The silent sea], Kaliningradskoe knizhnoe izdatelstvo, Kaliningrad, Russia. (In Russian)

Rozenfeld, M. K. (1946). Morskaya taina [Sea mystery], Detgiz, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Stepanov, V. A. (1974). Venok na volne [Wreath on a wave], Voenizdat, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Vsevolozhskiy, I. E. (1961). Neulovimy monitor [The elusive monitor], Krymizdat, Simferopol, Russia. (In Russian)

Vulis, A. Z. (1975). Khrustalny klyuch [The Crystal Key], Josh gvardiya, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. (In Russian)

Zhemaitis, S. G. (1965). Vzryv v okeane [Explosion in the ocean], Molodaya gvardiya, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Zuev-Ordynets, M. (1937). Khlopushin poisk [Khlopushin search], Chelyabgiz, Chelyabinsk, Russia. (In Russian)

[1]McGuire, I. (2016). The 10 Best Adventure Novels, Publishers Weekly [Electronic], available at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/tip-sheet/article/69690-the-10-best-adventure-novels.html (Accessed 26 February 2024).

[2]The Fifth All-Russian Congress of the Russian Communist Youth Union. 11-19 October 1922. Verbatim report, 1927. URL: https://rusneb.ru/catalog/000199_000009_006734975/ (Accessed 20 March 2024).

Thanks

The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant 24-28-01355 "Genre-discourse characteristics of the text as a function of lexical range".

Reference lists

Bakhtin, M. M. (1975). Voprosy literatury i estetiki [Issues of literature and aesthetics], Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Biber, D. (1986). Spoken and Written Textual Dimensions in English: Resolving the Contradictory Findings, Language, 62 (2), 384–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/414678(In English)

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across Speech and Writing, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Brine, J. J. (1986). Adult readers in the Soviet Union, Abstract of Ph.D. dissertation, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK. http://etheses.bham.ac.uk//id/eprint/1398/(In English)

Dell’Orletta, F., Montemagni, S. and Venturi, G. (2013). Linguistic Profiling of Texts Across Textual Genre and Readability Level. An Exploratory Study on Italian Fictional Prose, Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing Conference (RANLP-2013), Hissar, Bulgaria, 189-197. (In English)

Dralyuk, B. (2011). Bukharin and the “Red Pinkerton”, The NEP Era: Soviet Russia, 1921-1928, 5, 3-21. (In English)

Galve, G. I. (1998). The textual interplay of grammatical metaphor on the nominalization occurring in written medical English, Journal of Pragmatics, 30 (3), 363–385. (In English)

Gatiyatullina, G. M., Solnyshkina, M. I., Kupriyanov, R. V. and Ziganshina, Ch. R. (2023). Lexical density as a complexity predictor: the case of Science and Social Studies textbooks, Research Result. Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 9 (1), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.18413/2313-8912-2023-9-1-0-2(In English)

Gatiyatullina, G., Solnyshkina, M., Solovyev, V., Danilov, A., Martynova, E. and Yarmakeev, I. (2020). Computing Russian Morphological distribution patterns using RusAC Online Server, Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DeSE), Liverpool, United Kingdom, 393-398. https://doi.org/10.1109/DeSE51703.2020.9450753(In English)

Halteren, H. V. (2004). Linguistic Profiling for Authorship Recognition and Verification, Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL-04), Barcelona, Spain, 199-206. (In English)

Husband, W. B. (2006). Miraculous Horses: Reading the Russian Revolution through Soviet Children’s Literature, The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 67 (3), 553–594. https://doi.org/10.25290/prinunivlibrchro.67.3.0553(In English)

Hyland, K. (2009). Academic Discourse: English in a Global Context, Continuum, London, UK. (In English)

Jalilifar, A., Alipour, M. and Parsa, S. (2014). Comparative Study of Nominalization in Applied Linguistics and Biology Books, Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics, 5 (1), 24-43. (In English)

Klerides, E. (2010). Imagining the Textbook: Textbooks as Discourse and Genre, Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 2 (1), 31-54. https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2010.020103(In English)

Koppel, M., Argamon, Sh. and Shimoni, A. R. (2002). Automatically categorizing written texts by author gender, Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17, 401–412. (In English)

Kruskal, W. H. and Wallis, W. A. (1952). Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 47, 583–621. (In English)

Kupriyanov, R. V., Bukach, O. V. and Aleksandrova, O. I. (2023). Cognitive complexity measures for educational texts: Empirical validation of linguistic parameters, Russian Journal of Linguistics, 27 (3), 641-662. https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-35817(In English)

Malikova, M. (2006). «Sketch po koshmaru Chestertona» i kulturnaya situatsiya NEPa ["A Sketch on Chesterton's Nightmare" and the cultural situation of the NEP], Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2 (78), 32-59. (In Russian)

Manning, Ch. and Schütze, H. (1999). Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing, MIT Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Medvedev, V. B. and Solnyshkina, M. I. (2022). Technologies of Assessing and Enhancing Cohesion of Instructional and Narrative Texts, Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 342, 693-712. (In English)

Mendhakar, A. (2022). Linguistic Profiling of Text Genres: An Exploration of Fictional vs. Non-Fictional Texts, Information, 13 (8), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13080357(In English)

Montemagni, S. (2013). Tecnologie Linguistico-Computazionali E Monitoraggio Della Lingua, Studi Italiani di Linguistica Teorica e Applicata (SILTA), 42 (1), 145–172. (In Italian)

Paltridge, B. (1994). Genre Analysis and the Identification of Textual Boundaries, Applied Linguistics, 15 (3), 288-299. (In English)

Slater, J. G. (1989). The Politics of History Teaching: A Humanity Dehumanized?, Institute of Education University of London : distributed by Turnaround Distribution, London, UK. (In English)

Stites, R. (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society since 1900, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Swales, J. M. (2004). Research Genres: Explorations and Applications, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Vulis, A. (1986). V mire priklyucheniy. Poyetika zhanra [In the world of adventure. Genre poetics], Sovetskiy pisatel', Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)