Epidemics and World Literature: Transformations of Social Behaviour in Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”, A. Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, and A. Camus’ “The Plague”

Abstract

This study focuses on three significant works of world literature (Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”, Alexander Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague, Albert Camus’ “The Plague”), in which the main theme and artistic reference are centered around the spread of epidemics and the resulting human behaviours. Such themes (including Covid-19) have attracted and continue to attract numerous artists. The study aims to scrutinize the aforementioned three literary works and uncover the behaviours displayed by people during epidemics at the time of broader crises. The study has two main objectives: 1. to identify various models of human behaviour that emerge as a result of psychological pressure during moments of broader danger; 2. to interpret these models and uncover significant existential-ontological messages contained in their inner domains within the context of the literary texts in the context of these literary works. The scientific novelty of this study lies in its examination of the works of Boccaccio, Pushkin, and Camus, where epidemics are regarded as distinctive and crucial factors of the situation that give rise to behavioural deviations. These deviations, in turn, infuse the narratives with mystery and provide an opportunity to analyze and unveil various vulnerable and strong aspects of human psychology. The pertinence of the study stems from its interdisciplinary approach. It unfolds through a series of inter-interpretive-examination processes across diverse disciplines such as Literary Studies, Philosophy and Art. The methods of both general scientific approaches (analysis, comparison) and historical, literary studies, and the combination of image and text were used.

Keywords: Epidemics and World Literature, transformation of social behavior, Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”, Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, Camus’ “The Plague”, Cholera as a source of epidemic

Introduction

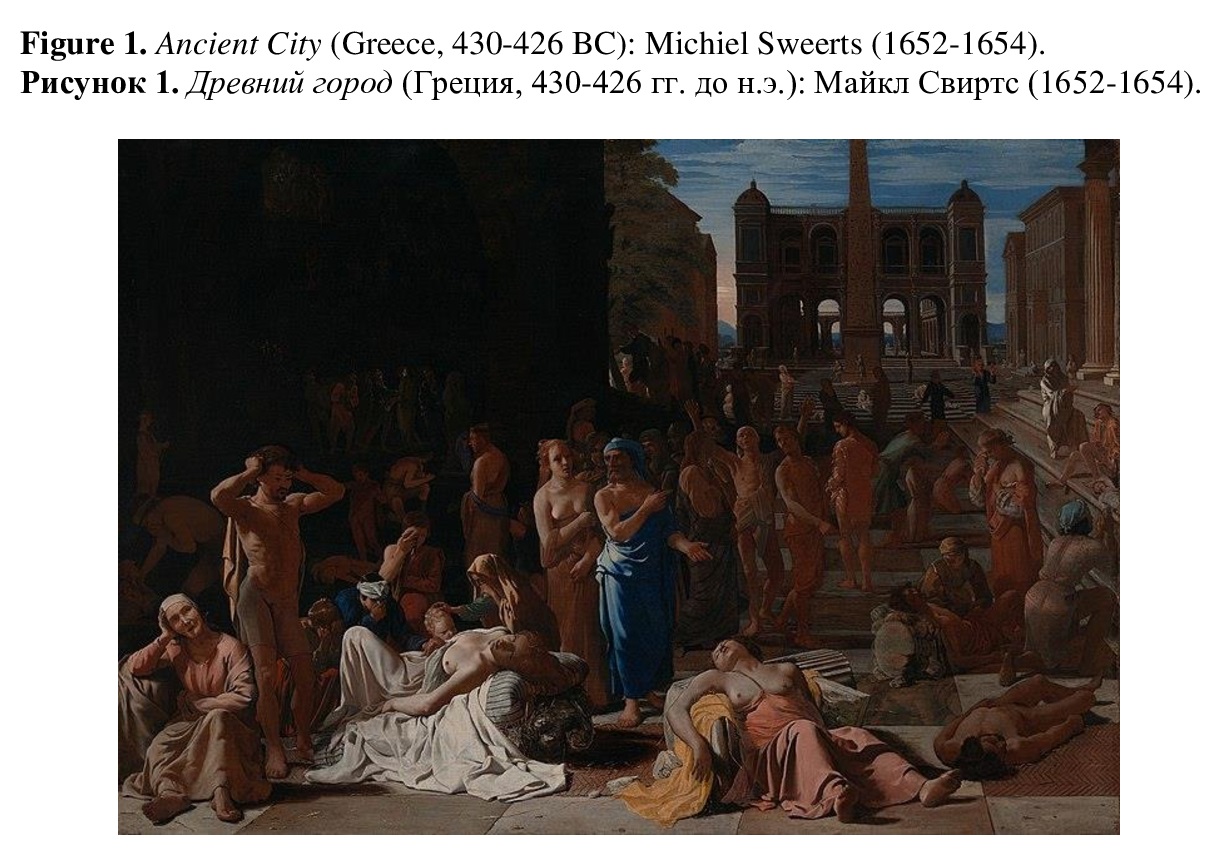

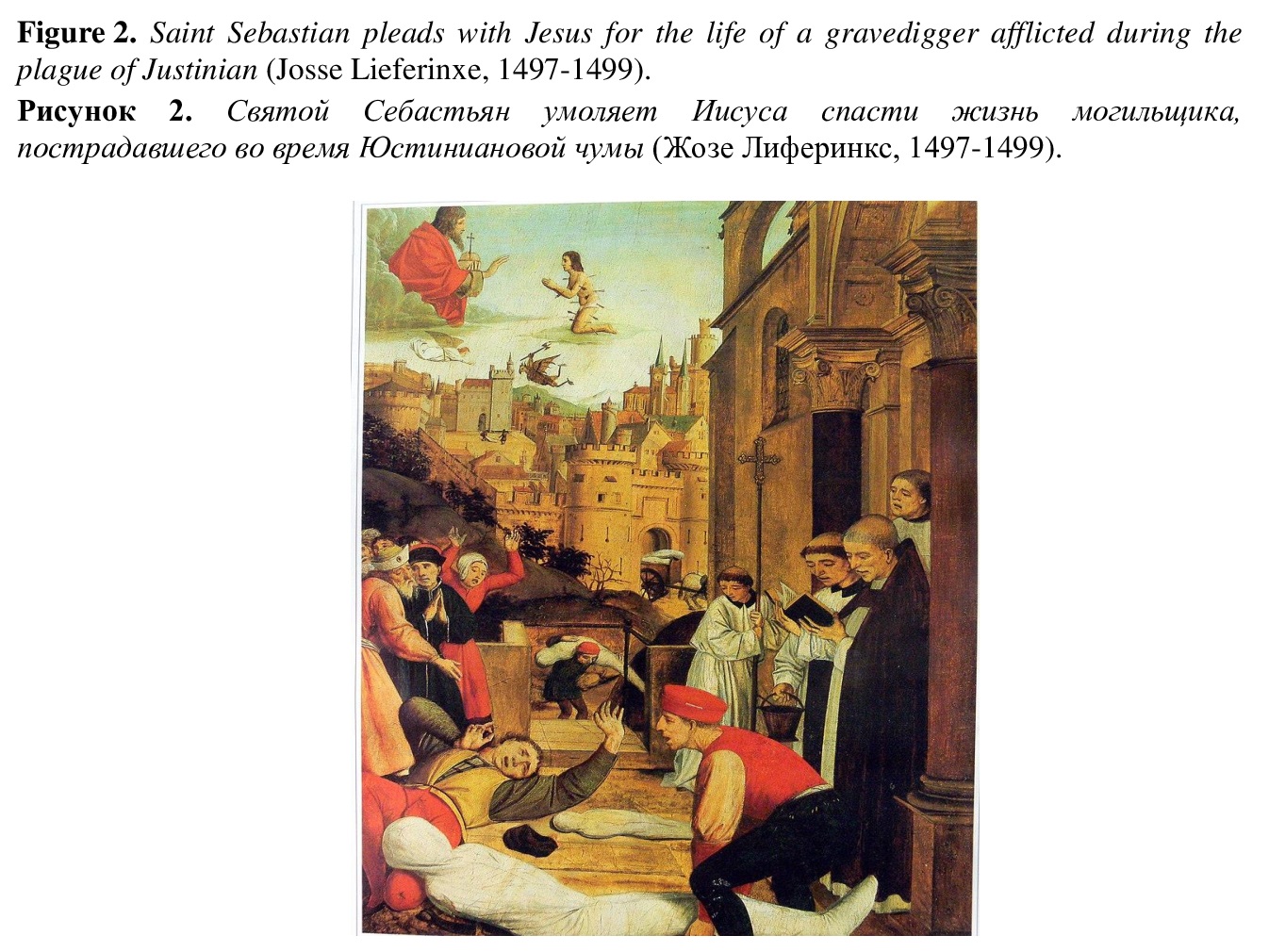

Epidemics (including COVID-19) have fascinated writers and artists of all times, and the world literature has long documented occurrence of epidemics[1] or pandemics[2] and what they are, as these life-threatening events have been experienced by mankind more than once. Over the centuries pathogens causing epidemics have been replaced with new ones; societies in which they spread have also changed; however, the way they affect human relations, politics, natural environment, social and economic stability carried over.

The phenomenon is emphasized by philosophical, anthropological, religious, sociological, political, and ethical depth and conception; it affects the socio-political stability of the whole world due to the closure of countries and cities.

Plague, typhoid, cholera, tuberculosis, measles, leprosy, and various flu viruses, which have turned from deadly diseases into phenomena and determined the being of people and continents and directed the thoughts, senses, social and civic behaviour of different societies, found their place in the world literature. They are perceived as a metaphor or symbol of chaos, collapse of cultures, lack of freedom, and destruction of societies. Though epidemics carry the idea of death in their inner domain, they are one step behind that idea and, nevertheless, force people to re-evaluate life, which is directly related to human psychology and behaviour. Epidemics have a wide spatial-temporal occurrence and clarify the gaps in socio-public hierarchies and in ecology, through which the spread of diseases takes place.

This profound problem is always closely related to social behaviour and the decline of moral, psychological, and spiritual standards. This profound problem is invariably associated with social behaviour and the decline of moral, psychological and spiritual standards. Diseases have a documented history, which includes their occurrence, development, and/or spread. These elements contribute to the definition of human behaviour, which leaves individuals with no alternative but to give due consideration and evaluation to issues vital for their existence. The way they are depicted in art and literature gives insights into the cultures and behavioural ecology of the day, shedding light on the human condition and responses to them.

Over the centuries, the severity of pandemics influenced not only societal behaviour but also how various artists responded to them. Various social behaviours, manifested as a result of the disorder, fear, emotional-mental influences and pressures caused by epidemics, have been captured by many great writers, from the ancient times: (Thucydides “The History of the Plague of Athens”[3], “The Bible”, Homer “The Iliad”[4], Sophocles “Oedipus Rex”[5], Aeschylus “Prometheus Bound”[6], Plutarch “Parallel Lives”), and the Renaissance authors (Boccaccio “The Decameron”, Shakespeare “Romeo and Juliet”), to the mysterious Samuel Pepys’ “The Great Plague of London”, Daniel Defoe’s “A Journey of the Plague Year”, Alan Edgar Poe’s “The Masque of Red Death”, Katherine Anne Porter’s “Pale Horse, Pale Rider”, Alexander Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre”, and Emile Zola’s biographical novels “The Mysteries Marseille”, from the point of view of moral choice Somerset Maugham’s “The Painted Veil”, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “Love in the Time of Cholera”, and Albert Camus’ “The Plague”, Margaret Atwood’s “Year of the Flood”, John Christopher’s “Death of Grass”, “World War Z”, etc.

In each of these works, the behaviour arising from disorder and fear is conveyed through aesthetic reference or individual message. In this context, the unity of humanity in the face of natural calamities becomes apparent. The human beings grapple with incomprehensible and disastrous forces, endeavoring to avoid isolation from the world and resisting immersion in the entanglements of disease and death mirrored by the epidemic.[7]

For this study, we have selected the works of three world-famous authors who dealt with the epidemics of their time, which claimed many lives: Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”, Alexander Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, and Albert Camus’ “The Plague”. Each of the three works we’ve chosen is a good illustration of one or the other of these. We have tried to show with these examples of selected works what impact pandemics have and how they are perceived by people.

Why have we considered the works of these authors? Thanks to their ideological-aesthetic references, we have been able to record three different models of human behaviour due to the mental states (stress) of people, which appear during a common danger and contain existential-ontological messages in their inner domains.

Escape from Society as a Self-Defense Mechanism

At the time of 1348 dreadful plague,[8] Boccaccio was in Florence. In his collection of novellas “The Decameron” (Boccacco, 1972: pp. 3-4), he described the horrors of those days (Kaniewski, Marriner, 2020: 7: pp. 162). Boccaccio survived through the whirlpool of the plague, but the pandemic took the lives of his loved ones, wife and daughter. In “The Decameron”, Boccaccio developed a distinct culture which may be perceived as the basis for fearlessness against the plague. Such a narrative of the manifestation of the will of spirit, and behaviour against death was especially important in the realm of the author’s personality. “To have compassion for those who suffer is a human characteristic which everyone should possess, especially those who needed comfort themselves in the past and have managed to find it in others” (Dante, 1969: pp. 7-191).

At the beginning of the book, the author describes the plight of the plagued, lifeless, inanimate, inconsolable, and deplorable Florence – hundreds of destroyed lives, divided families, helpless diseased, rotting corpses dumped in the streets and in houses. But the catastrophe is not encompassed only within these gloomy and dreadful scenes, but also in the fact that the epidemic is transmitted to the mundane life through people’s animalistic behaviour, perverted emotions, and corrupt traditions. Relatives forget each other, friends do not lend a helping hand, mercy and compassion are abolished, and humanism is absent. Moreover, many are engaged in amassing wealth, some in gluttony and prodigal life, and some, forgetting all kinds of decency, satisfy their passions. Such decay in human moral standards is more intolerable than the countless human victims, reminiscent of Dante’s “Hell”.

Although Dante’s Florence is depicted with transcendental action, Boccaccio’s Florence is demonstrated through real events. It is at this point that perhaps the works of Dante and Boccaccio intersect, juxtaposing the realms of fact and fiction, thereby enriching the human and divine comedies.

Petrified by the horror of death, pervasive immorality, and people’s animalistic behaviour, Boccaccio’s heroes (seven women and three young men) leave Florence to eschew from the corrupt mundane life, to leave a decent life and to preserve the dignity and common sense of a human being as a personality.

This is an escape (alienation) from the demoralized society, whose murky cavities of psychological and spiritual crisis are revived and restored by the young people through the force of reason, meaning, joys of life, art, love for the spiritual, and closeness with nature. This means that spiritual/moral purity is a metaphor in Boccaccio’s book and means “not sick”. But are they “spared” because of their moral position, and if we look at it from the point of view of modern perceptions then what does Boccaccio’s Decameron suggest about social distancing in modern society and/or the rest of us “sick” people?

They live in the bosom of nature and follow certain rules and order: “Each of these activities has the power to occupy a man’s mind either wholly or in part and to free it from painful thoughts, at least for a while, after which, one way or another, either we will find consolation or the pain will subside,” (Boccaccio, 1972: p. 5) writes Boccaccio in the introduction of his novel. Every day, a new king or a queen is appointed, they gather and tell stories to understand what is given to a man by nature, and this becomes a sacral (purification) ritual. From funny jokes, the characters gradually move to more serious ideas: man, humanism, love, political laws, power whims, religion, church, mundane life. Art begins to live through them. In this respect, “The Decameron” also possesses a great cognitive value. Integration into nature and meditations about nature create in Boccaccio’s characters the sense of freedom and the idea of world inviolability.

They become part of the universal harmony. It turns out that epidemics are also phenomena that reveal the best human qualities. They find their best human qualities away from the symbolized society and joining people who have the same values. The plague is perceived as cleaning society, where only the “cleanest” will survive.

The community of painters and writers is more socio-economically elite and privileged, both in ancient times and today. In order to overcome the chaos and the fear created by the epidemic, as a socio-psychological barrier, Boccaccio deliberately turns to culture. In a certain social environment (here, a demoralized society) in which an individual lives, fear as an important psychological phenomenon (fear for oneself and fear for loved ones) turns into clear manifestations of behaviour which are not in the realm of the form but that of the content - care, mercy, kindness, mutual assistance, and other manifestations. In this context of content, fear takes an existential-ontological significance for life. Boccaccio writes about this in the preface of “The Decameron”, “But although the pain has ceased, I have not forgotten the benefits I once received from those who, because of the benevolence they felt toward me, shared my heavy burden, nor will this memory ever fade in me, I truly believe, until I myself am dead” (Boccacco, 1972: p. 4).

This explains how the above example particularly affected him; it shows what people who care about each other are like. This is heaven as opposed to Dante’s hell.[9]

A human is a bio-psychological being, and his existence is observable not only in the biological (also, unification with nature), but also in the socio-cultural sphere.

The source of Boccaccio’s artistic depiction was the real world, and the hero was the real man whose thinking and actions could be perceived in the primary (and not only) sources of the meaning of existence. Boccaccio reveals the people who insisted on enjoying life, singing and joking, satisfying every wish if possible, laughing and approaching everything that happens with humor; this is the safest cure for the disease.

Art and culture ascend from a world marked by dirt and illness, forming the semantic connection that Boccaccio explores. The question remains: does this signify a revival of the dark ages? This rhetorical issue is still unresolved.

Homage[10] to the Epidemic

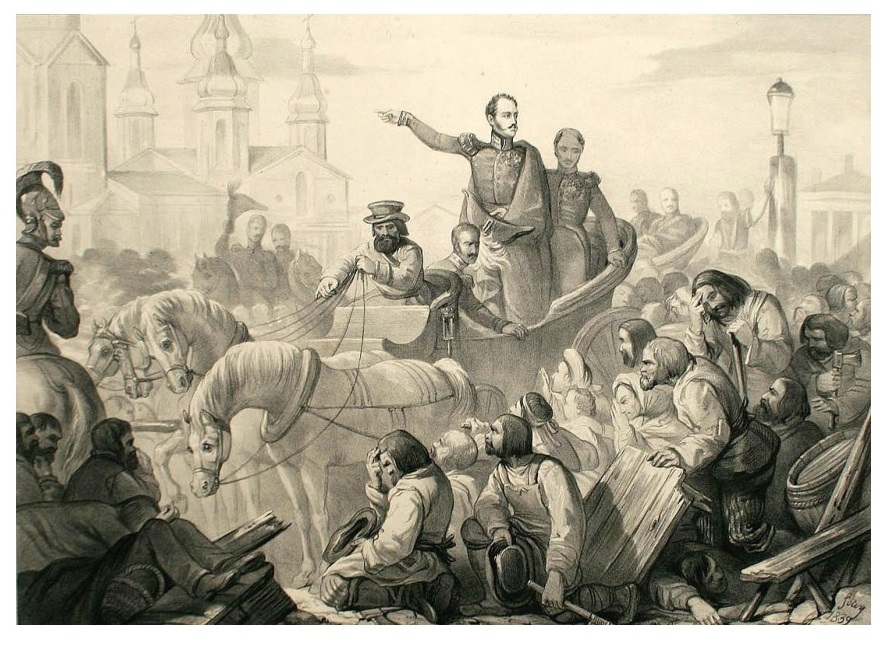

On 31 August 1830, after receiving Natalia Goncharova’s long-awaited consent to become his wife, Pushkin left for the Boldino family estate to relinquish ownership of the village of Kistenevo, which was a wedding gift from his father. His visit was supposed to take three weeks, but due to the rapid spread of cholera[11] and the impossibility of departure, Pushkin was forced to stay in Boldino for three months. During those three months of lockdown, Pushkin wrote most of his works, almost all the tales, thirty short poems, “Belkin’s Tales” and most of the “Eugene Onegin”, four little tragedies, including the “A Feast in the Time of Plague”.

Despite the hardships arisen from the epidemic, Pushkin tried to joke about a terrible disease. In a letter to Pyotr Pletnyov, we read, “The morbid cholera is next to me. Do you know what a beast this is? And see that he will run to Boldino, bite us all, and see that I will go to Uncle Vasiliy[12] and you will write my biography. <…> Oh, oh, my dear, what a miracle this village is! Imagine stone by stone; there are no neighbors; horserace as much as you please write at home as much as you want: no one will bother you. I will prepare such things for you – prose and poetry! Forgive me, my dear”[13] We read details and information on the growing dangers of cholera and delayed cases directly related to it, debts, not receiving news from his bride, even prevention and fight against the epidemic, in his letters. “…The death of Vasiliy Lvovich Pushkin again confused my plans. No sooner had I paid my debts than I was forced to pledge again. In the coming days I will be leaving for the village near the city to certify my rights…” (Pushkin, 1965, vol. 10: p. 303), “…The due date for my debt is next month, but I will not dare to pay you; I am not lying to you, neither does my wallet, the plague does, and the five quarantines made up for us” (Pushkin, 1965, vol. 10: p. 315), “I live in the village like on an island surrounded with water. I am waiting for favorable weather to get married and arrive in St. Petersburg, although I do not even dare to think about it” (Pushkin, 1965, vol. 10: p. 314), or: “…let him have a bath in chlorinated water and drink mint tea …If you could imagine how unbearable it is for me to receive these cursed letters…” (Pushkin, 1965, vol. 10: p. 320). Being in forced isolation, he entertained with letters himself and his young fiancée, Natalia Goncharova, with whom his marriage had been forcibly postponed for six months.

His witty letters are the best example of how it is possible to avoid sadness during lockdown, “The times of the plague are different, you are happy even for a pierced letter, you know at least you are alive, and that’s already good. …This is where we have reached: we are happy to be detained for two weeks in a carpenter’s hut and be given only bread and water”. This quote, like the previous one, is humorously used as a protection against the epidemic and as a mechanism for overcoming.

It is under these psychological circumstances that Pushkin wrote the tragedy “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, which seems to contradict Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”. Unlike the characters of “The Decameron” (seven ladies and three young men), who are educated, honest, and smart, Pushkin’s characters display a different behaviour by their way of thinking, their way of working. It is more important to view the stories of “The Decameron” in that context of love, although this is also a unique feast during the plague, but delicate and elegant, love- and art-inspired feast, created not from glasses full of wine, but from the attitude towards life and culture.

Figure 3.Nicholas I of Russia quelling a riot[14] on the Sennaya Square.

Рисунок 3.Николай I подавляет беспорядки на Сенной площади.

In general, Pushkin’s tragedy “A Feast in the Time of Plague” like Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” also carries a message that the disease cannot erase human spirit and creative abilities.

The Horror of Death as a Paradoxical Manifestation of Social Behaviour

In the autumn of 1830, Pushkin wrote his “Little Tragedies”, of which we have highlighted the tragedy “A Feast in the Time of Plague”[15], which is an unequal struggle between evil and kindness, light and dark, in which darkness overpasses the light, where a man is found by means of the fact of his existence.

What extremes in behaviour can a man on the brink of death exhibit? This constitutes the aesthetic reference of Pushkin’s tragedy. The passion portrayed by Pushkin in his play is the fear of death, and it is the adrenalin produced by the fear of imminent death that forces the heroes of the tragedy to display dysfunctional behaviour, accompanied by feasting.

A reasonable person always needs to affirm his sense of security. Pushkin’s heroes react to the lack of security with feasting, and it is the fact that they are on the verge of defenselessness and indifference, that drives them to a unique kind of a riot – holding a feast. This is the adverse reaction to the lack of security, the impossibility, and impassability of the situation, in which Pushkin’s heroes are physically present, and which leads them to the feeling of perfect freedom against the extremely accessible death. They have fun as if death does not exist. Pushkin’s heroes hold a feast, although it is not even appropriate to consider it a feast – merely several people sitting there, drinking, and enjoying life. This is an anti-death attitude and behaviour originating from the fear of death, which Pushkin creates through a feast, since the dark phantom of the plague wandering around the city constantly reminds them about itself, when every day, new carts loaded with dead people pass through the streets.

Louisa:

(Reviving)

I dreamed I saw

A hideous demon, black all over, with white eyes...

He called me to his wagon. Lying in it

Were the dead-and they were muttering

In some hideous, unknown language

Tell me: was it after all a dream?

Did the wagon pass? (Pushkin, 1960, vol. 4: p. 376-377)

Some of the participants of the feast bury the tragedy of separation in poetry and songs and surrender to the grief. They are deeply aware that even at the table of the feast, each of them is alone and defenseless against the impartial disease and the world. The Scottish girl, Mary, also demonstrates such behaviour. Mary’s song is a confession of a person living with the feeling of sinfulness and repenting through a song.

If my springtime too is blighted,

If the grave my lot must be,

You whom I have loved so long,

Whose love was always joy to me -

Oh, come not near then to your Jenny,

No last kiss on her pale lips lay,

Watch, but watch you from afar off

When they bear her corpse away (Pushkin, 1960, vol. 4: p. 375)

The idea of such a feast is mad fun and acceptance of a coffin with pleasure. Freedom and death are equalized. A paradox that creates the mathematical countdown of the impossibility of existence that is peculiar to those who commit suicide, and is more than the instinct of self-preservation. Also noteworthy is the character of Walsingham, who is the chairman of the party and the main character of the tragedy. Walsingham does not endure. He sings a hymn, homage to the plague, and glorifies his kingdom as numbness in a battle or on the edge of a dark abyss.

Chairman

(sings)

Old Man Winter we’ve beat back;

That’s how we’ll meet the Plague’s attack!

We’ll light the fire and fill the cup

And pass it round-a merry scene!

And after we have all drunk up,

We’ll sing: All hail to thee, dread queen! (Pushkin, 1960, vol. 4: p. 378)

-----------------------------------------------

So-for the Plague a hearty cheer!

The grave’s dark doesn’t make us fear,

If Death calls us-we’ll answer coldly.

We’ll join in quaffing from the keg,

Rose-maidens’ scents we drink in boldly,

Scents, it may be-full of the Plague! (Pushkin, 1960, vol. 4: p. 378-379)

The illogical state Pushkin’s heroes are in and the behaviour they exhibit, are created as a result of a psychological defeat, since a human being may not be and remain within the realm of identification of reason, and consequently, of logic. Walsingham has fun with his friends, attempting to overcome the created ontological crisis.

The feast is endless. In the metaphysical mesosphere of the divine and human are Walsingham and the priest, the former bearing victory over the plague, and the latter - victory over himself. The chairman remains immersed in his deep thoughts; however, the fact that among the participants of the feast, the priest is not a cowardly one at all, but in fact, the only reasonable person at the feast, who threatens others with the last judgment and tries to send them home.

Priest

I adjure you by the holy blood

Of the Savior crucified for us:

Halt this monstrous feast, if ever

You hope to meet again in Heaven

The souls of those whom you have lost.

Go, each of you, to your homes! (Pushkin, 1960, vol. 4: p. 379)

The Chairman answers:

Chairman:

Our homes

Are sorrowful-youth loves gaiety. (Pushkin, 1960, vol. 4: p. 379)

Alexander Pushkin’s tragedy “A Feast in the Time of Plague” encompasses the aesthetic reference of man’s mortality and finiteness of life, which at the same time, is also an ontologically undeniable fact. In that fear-induced existential-ontological chaos, Pushkin’s heroes meet face the reality accompanied by the feelings of despair, anxiety, loneliness, and abandonment, which gives birth to another psychological extreme – hatred for life.

Its demarcation line from life itself is the existential or metaphysical horror – the world without God, but also without the devil, when a man is deprived of the possibility of any ontological choices. The heroes of the tragedy do not accept the humiliating existence of death and try to overcome the horror emanating from it, which will lead them through the path of immortality; therefore, in the end, everyone remains with themselves. Only Walsingham doubts whether he did the right thing when he did not follow the priest’s advice, and whether he could continue to resist the horrors of death with the power of his spirit. In addition, if Boccaccio’s heroes voluntarily leave the social and moral-psychological perverted transformations, ethical, moral, and psychological desolation and descent into nature, towards the spiritual transformation, Pushkin’s heroes voluntarily choose the state of ethical, moral, psychological, and social disaster, in which the fear of not only death and torment, but also powerlessness is present.

The 19th-century Scottish writer John Wilson’s play does not have such an end: Pushkin conceived this. The climax, the culmination (Walsingham’s momentary weakness, pious life, and faith in God), in this case is not equal to retreat, but is Walsingham’s rejection. A whole generation leaves deprived of future and hope, deprived of aging and love.

It should be noted that Soviet literary critics (Ovsyaniko-Kulikovsky, 1989) previously commented that this is not a celebration of depravity (Aikhenvald, 2017), but an individual behaviour of the subject and at the same time a search for a way out of existential despair. This is a farewell to life and is also a form of rebellion, because especially dangers create rebellion, and especially then a person, who always strives for immortality, reevaluates life and becomes stronger.

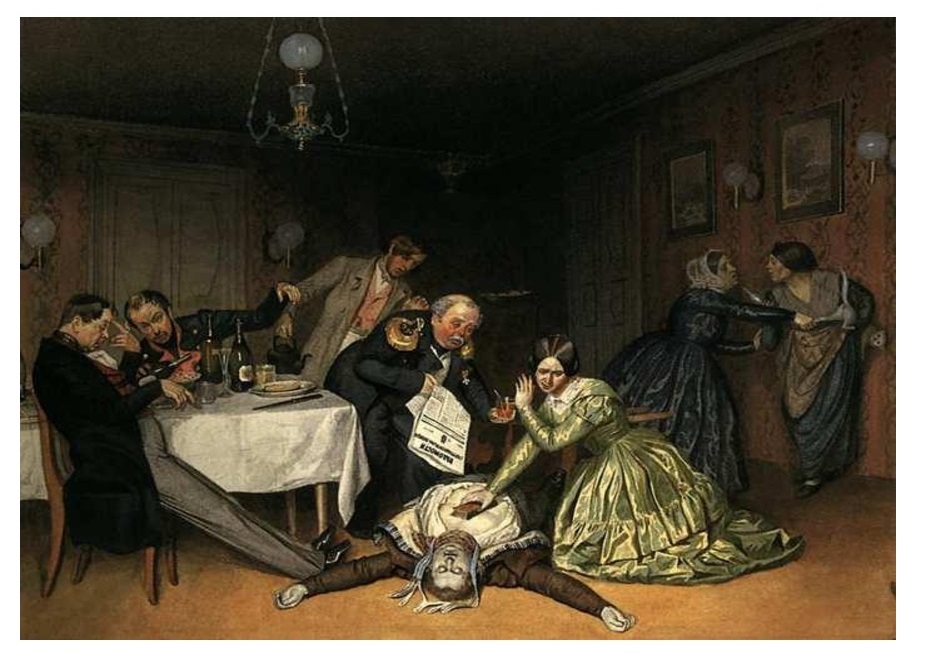

The Isolated City as a Phenomenon of Social Imprisonment

“The Plague”, a philosophical novel written by Albert Camus in 1947, is a farewell to the illusions of antiquity and the Renaissance. The novel depicts the 1940s, and it is clear that Camus means the brown plague wandering around Europe at the time, which reigned in Europe and, which, according to the writer, became a catalyst for world evil, since people had to wander around the world, seeking refuge[16].

The three selected books are the turning points of the story: Boccaccio – Dark Ages to the Renaissance; Pushkin – from pre-industrial to industrial; Camus - from pre-war to post-war. Camus’ Brown Plague is a metaphor for fascism, the brown plague is moral/ethical depravity.

If in Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” people voluntarily left the social environment in which they lived (it was their social choice), and Pushkin’s heroes held a feast accompanied by fear, in Camus’ “The Plague” everything happens forcedly.

Figure 4. “It is Cholera to Blame” (1846-1860): Pavel Fedotov’s painting shows a death from cholera in the mid-19th century.

Рисунок 4. «Во всем виновата холера» (1846-1860): На картине Павла Федотова изображена смерть от холеры в середине XIX века.

While working on the novel “The Plague”[17], Camus, parallel to his diary notes, conveys the atmosphere of suffocation from which people suffered, and the atmosphere of danger and alienation in which they lived in the days of the Plague, at the same time exacerbating and rendering ontological significance to the idea: “The liberating plague. Happy town. People live according to different systems. The plague: abolishes all systems. But they die all the same. Doubly useless. A philosopher is writing an “anthology of insignificant actions”. He will keep a diary of the plague, from this point of view. He realizes that he had not understood Thucydides and Lucretius until then.

His favorite phrase: “It is highly probable.” “The streetcar company had only 760 workers available instead of 2,130. It is highly probable that this is due to the plague.” A young priest loses his faith at the sight of the black pus flowing out of the wounds. He takes his holy oil away. “If I get out alive….” But he does not. Everything must be paid for. The bodies are taken away in streetcars. Whole strings of cars, filled with flowers and dead bodies, drive along the cliffs. They immediately fire all the conductors: the passengers no longer pay. The agency “Ransdoc-S.V.P” gives all information on the telephone “Two hundred victims today. A charge of two francs will be added to your telephone bill.” “Impossible, I’ m afraid, no more coffins for four days. Consult the Transport Authority. A charge….” The agency advertises on the radio. “Do you want to know the daily, weekly, or monthly number of plague victims? Phone “Information Please” - five lines: 353-91 and…” The town gates are closed. People die cut off from the world and packed together. One gentleman, however, keeps to his habits. He continues to dress for dinner. One by one, the members of his family disappear from the table. He dies with his meal in front of him, still dressed for dinner. As the maid says: “Well, there’s something to be said for it. We don’t need to get him ready for the funeral” (Camus, 2009: p. 75).

In the previous two works: Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” and Pushkin’s tragedy “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, those who adhere to moral purity are saved, but in Camus’ “The Plague” this is not the case. What does this circumstance tell us? It confirms that the ideology of fascism is mediated by moral decline, and demoralization.

The perception of freedom in society, in general, materializes through the selectivity of a man as a social subject. In Camus’ novel, throughout the epidemic, that choice is absent, the city gates are closed, the city becomes a prison, and to comprehend the reality imposed on him and his own actions arising from it, a man is not satisfied only with the epistemological orientation because social coercion does not disappear from it. The actions of the novel “The Plague” take place in the city of Oran where the terrible plague spreads from rats, and takes the local inhabitants captive. In the preface of the novel, the image of the city is comparable to a crematorium with a chimney smoking day and night, like in Auschwitz: “What is more exceptional in our town is the difficulty one may experience there in dying. “Difficulty,” perhaps, is not the right word “discomfort” would come nearer. Being ill is never agreeable but some towns support you, so to speak, when you feel sick; in such towns, in a way, you can afford to stay. A diseased person needs a gentle touch, he likes to have something to rely on, and that is natural enough. But at Oran the violent extremes of temperature, the exigencies of business, the uninspiring surroundings, the sudden night falls, and the very nature of its pleasures call for good health. And the diseased person is all alone out there. Think what it must be for a dying man, trapped behind hundreds of walls all sizzling with heat, while the whole population, sitting in cafes or hanging on the telephone, is discussing shipments, bills of lading, discounts! It will then be obvious what discomfort attends death, even modern death, when it waylays you under such conditions in a dry place” (Camus, 1991: p. 6).

The author creates the locked territory of the prison-city, which is detached from the rest of the humanity by lockdown, since the plague implies separation even from the sea: “to see the sea, you always have to go to look for it” (Camus, 1991: p. 7).

Camus depicts the horrible epidemic of the plague as a precondition for violence, fear, chaos, disease, fascism, and death, which is at the same time an existential symbol of the inviolable and unchanging existence of a human in nature and the universe. Dr. Rieux tells the story of events without any special artistic tools, but each thought he utters opens a new aesthetic link in the realm of man-society-state-humanism-absurdity, in the inner realm of which Camus is faithful to the Ecclesiastes[18].

The dreadful disease is aggravating the city. The city gates get closed. Life comes to a halt, as the initial shock following the janitor’s demise transforms into panic. Yet, this upheaval was less terrible than horrors of another epidemic, World War II and the fascism it gave rise to.

Noteworthy is the preface of the novel, which Camus borrowed from Daniel Defoe: “It is as reasonable to represent one kind of imprisonment by another, as it is to represent anything that exists by that which doesn’t” (Camus, 1991: p. 5).

Camus’ characters are idealists rebelling against the absurdity of the plague; they fight for their rights of the humanistic values they have adopted - love, creation, humanism, friendship, faith in God, even laziness, and some ridiculous habits: “…the first thing that plague brought to our town was exile. …It was undoubtedly the feeling of exile, that sensation of a void which never left us, that irrational longing to hark back to the past or else to speed up the of time…” (Camus, 1991: p. 46).

When we regard the world as a staging, it opposes reason and fundamentally chains a man, depriving him of any type of freedom, however strongly the will emphasizes and demands freedom. In that case, both are perceived as extremes, as long as the main thing – the fear of compromising and surrendering to death – still exists: “There is no freedom for man so long as he has not overcome his fear of death. But not through suicide. In order to overcome, one must not surrender. Be able to die courageously without bitterness” (Camus, 2009: p. 115). Camus’ heroes are realists. They work in medical institutions, and help patients, realizing that they will not be able to defeat the plague. Among them, there are people who give in and accept the prison-world.

The narrator, Dr. Rieux, notes: “…when you see the misery it brings, you’d need to be a madman, or a coward, or stone blind, to give in tamely to the plague” (Camus, 1991: p. 46).

Here is what Camus tries to convey to the reader through the doctor’s character – people must resist the “scourge” of evil (= nazism). It’s not about running away or removing their self, it’s about standing and fighting. Camus writes about a fictional-metaphorical plague, while Boccaccio and Pushkin document real plagues in an attempt to uncover behavioural symbolism related to human psychology. This analysis is the best opportunity to consider how fiction has influenced society in three different periods.

Delicate allusions and references to famous authors and world literary and philosophical sources weave the encoded cultural pattern of the novel and demonstrate to the reader the absurdity of the situation and the slavish inner world of a human being. Within this context, culture does not save a man from barbarism, but opposes to it the free will, again making the axis of this opposition the psychological factor – fear. With the aesthetic reference of will and freedom, Camus perceives the power of human desire that leads to eternal salvation or separation from it. And its assertion is clear and convincing, since the prison-reality contradicts the human will, and only the impulse of necessity is present, which deprives will of its basis. Unfounded will opposes reason and fundamentally enchains a human being. A man becomes unfree within another imprisonment – coercion, which is the absurdity of the situation and which conditions the psychological factor – fear: “See him there, that angel of the pestilence, comely as Lucifer, shining like Evil’s very self! He is hovering above your roofs with his great spear in his right hand, poised to strike, while his left hand is stretched toward one or other of your houses. Maybe at this very moment his finger is pointing to your door, the red spear crashing on its panels, and even now, the plague is entering your home and settling down in your bedroom to await your return. Patient and watchful, ineluctable as the order of the scheme of things, it bides its time. No earthly power, nay, not even, mark me well, the vaunted might of human science can avail you to avert that hand once it is stretched toward you. And winnowed like corn on the blood-stained threshing-floor of suffering, you will be cast away with the chaff” (Camus, 1991: p. 62).

There is no phenomenon in nature, the creation of which requires will, and it simply does not exist because it abolishes not only the perception of free will, but also the will as such, replacing it with intellect. The will opposes coercion, which is not separable from necessity. And developing, a man perceives himself as an integral part of that mesosphere. Just as the will is subject to reason, so does the issue of freedom develop within the realm of cognition, since not only will but also freedom equals to reason. There was only one person among the citizens, on behalf of whom Dr. Rieux could not speak. That person was Tarrou, who had once told him, “His only real crime is that of having in his heart approved of something that killed off men, women, and children. I can understand the rest, but for that I am obliged to pardon him” (Camus, 1991: p. 189).

It is hard to view Camus’ prison-city in the semantic domain of sanitary sanctuary for two opposite reasons: first, it is identified with Auschwitz – violence and coercion, and second, however careless, the sanitary sanctuary leaves a humanistic trace of utility in the human consciousness, since it is activated when it is too late, and when it is necessary to break one of the key factors of healthcare – information. The plague raged from April to February. The end of the book is impressive: liberation and the enjoyment of freedom quickly erase the realities of the recent past from people’s memory. The inhabitants of the city celebrate the retreat of the disease and their victory, exclaiming with relief, yet Camus testifies, “Such joy is always imperiled. He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city” (Camus, 1991: p. 200).

Conclusion

The study of Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”, Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague” and Camus’ “The Plague” has led us to the conclusion that throughout the history of all civilizations, man has held a special place.

Thus, in Boccaccio’s work, the new generation stands out from the old, rising above it, while the plague cleanses, divides, and washes away all the traces of the past.

In Pushkin’s tragedy, the existential, cognitive, and experiential manifestations of man are reflected, emerging through the corruption revealed by the loss of the self. Here, the new and old generations do not separate but suffer together. The plague in this context exposes all the base qualities of human nature, resists vile passions, and allows time for self-purification.

A. Camus’ heroes are realists – they work in medical facilities, helping the sick, knowing they won’t be able to overcome the plague. Among them are those who surrender and accept the prison-like world. In all three literary works studied in this article, the epidemics contribute to the revelation of human nature and inner traits, exposing the fundamental relationships between the individual and nature, society, people, and the writer’s own self. Through the ideological and aesthetic references in Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”, Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague” and Camus’ “The Plague”, we have also concluded that during times of universal danger, a person, regardless of their will, may find themselves in compulsory phases of confinement or isolation, and this circumstance can create numerous existential-ontological challenges for them.

A deep look into the study of these three works also shows that the heroes of Boccaccio (leaving the city plagued by the epidemic), Pushkin (celebrating a feast in the streets during the plague), and Camus (perceiving the city as a prison) are individuals who strongly resist the threats of the epidemic, attempting to confront existential and ontological challenges across Boccaccio’s, Pushkin’s, Camus’, and other historical periods. We know that this also happened in the 21st century during COVID-19. These are the crucial messages contained in the works we have studied. “The Decameron”, Pushkin’s “A Feast in the Time of Plague” and Camus’ “The Plague” continue to remain valuable masterpieces in world literature and unique tools of intercultural communication.

[1] Epidemic (from the Greek ἐπιδημία - prevalence among the people), mass distribution of any infectious disease nor, significantly higher than the usual level of its prevalence in this territory. More often than not, the population is aghast parts of the country or several Countries (Briko, 2017, v. 35: p. 407).

[2] Pandemic (from the Greek πάνδημος - universal, all-national), a large-scale epidemic that can cover the entire country Well, several neighboring countries and even continents. Characteristics of a very large number of left-wingers (often up to several million people) and duration (from a year to tens of years). More often in the history of mankind, the pandemic of cholera, influenza, plague, smallpox has been described. (Zharov, 2014, v. 25: p. 208).

[3] Thucydides (460-395 BC) was a Greek historian and Athenian general. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens. Thucydides has been called the father of “scientific history”, and of political realism (Thucydides, 2022).

[4] In the prehistory of Homer’s “The Iliad”, Apollo sends a plague to the Athenian warriors with his arrows to avenge his priest Chryses, forcing them to return Chryses’ daughter to him.

[5] The scene of the tragedy of Sophocles’ “Oedipus Rex” is the city dying of the plague. The gods demand the surrender of the murderer. It is noteworthy that ideal conditions for the development of civilization are not assumed in the writing. Nevertheless, even in those conditions the Greeks do not stop loving life. On the contrary, the culture flourishes. Musicians, playwrights, and poets compete. Pictures and sculptures are placed in squares and temples to raise public taste. Olympic Games are held, ships are built, new trade routes and connections, unique architectural monuments are created. Here is the semantic reference of the Hellenes to overcome the epidemic and to put chaos in order.

[6] The myth of Prometheus tells how civilization saves man from death but there is an ancient, unusual interpretation in Aeschylus’ tragedy “Prometheus Bound”. Zeus decides to destroy people because they are useless and ugly. Prometheus, disobeying him, saves people, arguing that Zeus did not create them so he cannot kill them. Wise Prometheus endows people with free will, gives them intelligence, and inspires with the fire of creation. For the sake of survival and development, Prometheus teaches them all crafts, knowledge, arts, putting medicine first in order to eradicate all evil and violent diseases because a free, reasonable, and active person is less dependent on fate.

[7] The ancient Greeks perceived epidemics and diseases as punishment for those who violated divine laws. Describing the essence of the world, the Greeks relied on harmony, the universe, and humanistic values, as culture and civilization withstood natural disasters and destructions. They were trying to save themselves and the world.

[8] This deadly plague is also called the Black Death, the causative agent of which is the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Yersinia pestis (formerly: Pasteurella pestis) is a gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillus bacterium without spores that is related to both Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, the pathogen from which Yersinia pestis evolved and was responsible for the Far East scarlet-like fever (Stathakopoulos, 2018; Arrizabalaga, 2010). It is a facultative anaerobic organism that can infect humans via the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) (Willem, 2018: p. 3). The Justinian plague (bubonic plague) also attacked the Sasanian lands. It causes the disease plague, which caused the Plague of Justinian and the Black Death, the deadliest pandemic in recorded history (Robb, Cessford, 2021: pp. 101-112; Snowden, 2019; Doherty, 2021). Plague takes three main forms: pneumonic, septicemic, and bubonic. Yersinia pestis is a parasite of its host, the rat flea, which is also a parasite of rats hence Yersinia pestis is a hyperparasite. In 2013, researchers confirmed earlier speculation that the cause of the plague of Justinian was Yersinia pestis, the same bacterium responsible for the Black Death (1346-1353) (Cheng, 2014). Ancient and modern Yersinia pestis strains closely related to the ancestor of the Justinian plague strain that have been found in the Tian Shan, a system of mountain ranges on the borders of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and China (Spyrou et al, 2022: pp. 718–724), suggesting that the Justinian plague originated in or near that region (Eroshenko, 2017; Damgaard, 2018). However, there would appear to be no mention of bubonic plague in China until the year 610 (Sarris, 2002: p. 171).

[9] Boccaccio wrote historical works (“The Life of Dante Alighieri”, about 1360, published in 1477), gave public lectures. Il Sommo Poeta is called “Dante in Italy” (“Supreme Poet”) and Il Poeta. Dante, Petrain and Boccaccio are called “Three Fountains”. Dante is often called “Father of the Italians” and one of the great writers of Western civilization (Haller, 2012: p. 244; Murray, 2003).

[10]Homage - a tribute. It is a feudal ritual of self-recognition of vassals (small rulers) in Western Europe. The vassal, without a belt and a sword, knelt before his master, paid homage, declared his humility and obedience, and proceeded to fulfilling his rights and duties within his territory (OZ 1877 1 533). See: (Historical Dictionary of Gallicisms in the Russian Language: 2010).

[11] Through Pushkin’s tragedy “A Feast in the Time of Plague”, we have moved forward 500 years from Boccaccio’s “The Decameron”. Of course, this is a huge leap, and covers the Black Death of the 14th century. However, it should be noted that during those 500 years, another widespread plague took place in 1665-1666 in London, which was also called the Great Plague and claimed many lives (about 68.596).

[12] The poet’s uncle, Vasily Pushkin, died on August 20, 1830.

[13] Alexander Pushkin to Pyotr Pletnyov: September 9, 1830 (Pushkin, 1965, vol. 10: p. 306).

[14] Cholera riots (Cholera riots in Russian) broke out among the urban population, peasants, and soldiers in 1830–1831 when the second cholera pandemic reached Russia.

[15] This tragedy by Pushkin is a free translated adaptation of the first act of the 19th-century Scottish poet John Wilson’s play “The City of the Plague” which was dedicated to the 1665 London Plague. Only the Chairman’s and Mary’s songs are rhymed and belong to Pushkin’s pen. The title “A Feast in the Time of Plague” has since become an idiom.

[16] Camus used the cholera as a source material of epidemic that killed a large proportion of Oran’s population in 1849, but set the novel in the 1940s. Oran and its surroundings were struck by disease several times before Camus published his novel. According to an academic study, Oran was decimated by the bubonic plague in 1556 and 1678, but all later outbreaks (in 1921: 185 cases; 1931: 76 cases; and 1944: 95 cases) were very far from the scale of the epidemic described in the novel (Aronson, 2017).

[17] “The Plague” is considered an existentialist classic despite Camus’ objection to the label (Camus, 1970). In an interview on 15 November 1945, Camus said: “No, I am not an existentialist.” The novel stresses the powerlessness of the individual characters to affect their own destinies. The narrative tone is similar to Kafka’s, especially in “The Trial”, whose individual sentences potentially convey multiple meanings; the material often pointedly resonating as stark allegory of phenomenal consciousness and the human condition.

[18] “The Plague”: Second edition: Bible: Deuteronomy, XXVIII, 21; XXVIII, 24. Leviticus, XXVI, 25, Amos, IV, 10. Exodus, IX, 4; IX, 15 XII, 29. Jeremiah, XXIV, 10, XIV, 12; VI, 19; XXI, 7 and 9. Ezekiel, V, 12; VII, 15. “Everyone is looking for their own cross, and when they find it, they feel that it is too heavy. May it not be said that I was unable to carry my cross” (Camus, 2009: p. 100).

Thanks

The work was supported by the Higher Education and Science Committee of RA, within the framework of Research project No 23PTS-6B005.

Reference lists

Aikhenvald, Yu. I. (2017). Siluety russkikh pisateley (Silhouettes of Russian Writers), in 2 Books, Book 1, Direct-Media, Moscow, Berlin, Russia, Germany. (In Russian)

Damgaard, P. d. B., Marchi, N., Rasmussen, S. et al. (2018). 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes, Nature, 557, 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2(In English)

Doherty, P. (2021). An Insider’s Plague Year, Melbourne University Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.1176880(In English)

Eroshenko, G. A., Nosov, N. Y., Krasnov, Y. M., Oglodin, Y. G., Kukleva, L. M., Guseva, N. P., Kuznetsov, A. A., Abdikarimov, S. T., Dzhaparova, A. K. and Kutyrev, V. V. (2017). Yersinia pestis strains of ancient phylogenetic branch 0.ANT are widely spread in the high-mountain plague foci of Kyrgyzstan, PLoS ONE 12(10): e0187230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187230(In English)

Haller, E. K. (2012). Dante Alighieri, in Matheson, L. M. (ed.), Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints, Vol. 1, Greenwood, Santa Barbara, USA, 243–271. (In English)

Kaniewski, D., Marriner, N. (2020). Conflicts and the spread of plagues in pre-industrial Europe, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7, 162. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00661-1(In English)

Murray, Ch. (2003). Human accomplishment: the pursuit of excellence in the arts and sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950 (1st ed.), Harper Collins, New York, USA. (In English)

Ovsyaniko-Kulikovsky, D. N. (1989). Literaturno-kriticheskiye raboty (Literary critical works). In 2 Vols., Vol. 1. Articles on the theory of literature; Gogol; Pushkin; Turgenev; Chekhov: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow, Russian SFSR. (In Russian)

Robb, J., Cessford, C., Dittmar, J., Inskip, S. A. and Mitchell, P. D. (2021). The greatest health problem of the Middle Ages? Estimating the burden of disease in medieval England, International Journal of Paleopathology, 34, September, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2021.06.011(In English)

Rossi, L. R. (1958). Albert Camus: The Plague of Absurdity, The Kenyon Review, 20, 3, 399–422. (In English)

Sarris, P. (2002). The Justinianic plague: origins and effects. Continuity and Change, 17, 2, August, 169–182. (In English)

Snowden, F. M. (2019). Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvqc6gg5(In English)

Spyrou, M. A., Musralina, L., Gnecchi Ruscone, G. A., Kocher, A., Borbone, P.-G., Khartanovich, V. I., Buzhilova, A., Djansugurova, L., Bos, K. I., Kühnert, D., Haak, W., Slavin, P. and Krause, J. (2022). The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia, Nature, 606, 718–724. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04800-3(In English)

Willem, F. (2018). Studies in the History of Medicine in Iran, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, USA. (In English)

Corpus Materials

Aronson, R. (2017). Albert Camus, in Zalta E. N (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer Edition, available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/camus/ (Accessed 15 March 2025) (In English)

Arrizabalaga, J., Bjork, R. E. (ed.) (2010). The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. DOI: 10.1093/acref/9780198662624.001.0001 (In English)

Briko, N. I. (2017). Epidemic, in Bolshaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya [Great Russian Encyclopedia], 35, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Boccaccio, G. (1972). The Decameron, Translated by Vahuni, S., Hayastan, Yerevan, Armenian SSR. (In Armenian)

Camus, A. (1991). The Plague, Translated from French by Keshishyan, G., Apollo, Yerevan, Armenia. (In Armenian)

Camus, A. (2009). Iz zapisnykh knizhek (Notebooks): Copybook number III: April 1939 to February 1942. Translated from French by Grinberg, O., Malchina, V., Galtseva, Y., Ast, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Camus, A. (1970). Lyrical And Critical Essays, Translated by Kennedy, E. C., Thody, Ph. (ed.), Vintage Books, New York, USA. (In English)

Cheng, M. (2014). Plague DNA found in ancient teeth shows medieval Black Death, 1,500-year pandemic caused by same disease, National Post, January 28. (In English)

Dante, A. (1969). The Divine Comedy, Translated by Tayan A., Academy of Sciences of the Arm. SSR, Yerevan, Armenian SSR. (In Armenian)

Plutarch (2001). Parallel Lives, Sargis Khachents, compiled and translated from ancient Greek by Grkasharyan S.,Yerevan, Armenia. (In English)

Pushkin, A. (1960). Set of Works in 10 Vols, Vol 4., Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, Moscow, Russian SFSR. (In Russian)

Pushkin, A. (1965). Complete Set of Works in 10 Vols, Vol. 10, Letters (1815-1837), Academy of Sciences of the USSR, The Institute of Russian Literature “Pushkin’s House”, Nauka, Moscow, Russian SFSR. (In Russian)

Stathakopoulos, D. (2018). Plague, Justinianic: Early Medieval Pandemic, in The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquit, Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. DOI: 10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001 (In English)

Thucydides (2022). The History of the Plague of Athens, Legare Street Press, London, United Kingdom. (In English)

Yepishkin, N. I. (2010). Istoricheskiy slovar’ gallitsizmov russkogo yazyka [Historical Dictionary of Gallicisms in the Russian Language], Dictionary Publishing House ETS., Moscow, Russia (In Russian)

Zharov, S. N. (2014). Pandemic, Bol’shaya rossiyskaya entsiklopediya [Great Russian Encyclopedia]. vol. 25. Moscow, Russia. (InRussian)