Sudden Fiction Through the Lens of Decoding Stylistics

Abstract

Objective: The main purpose of the research is primarily to consider different types of stylistics focusing on decoding stylistics and its basic features, such as coupling, convergence, semantic repetition, salient feature and text strong position together with defeated expectancy. The subsidiary goals are to examine sudden fiction as a very specific genre in the prism of decoding stylistics and to specify types of foregrounding typical of it.

Background: Analysis of literature shows that various types of stylistics are based on different principles: types of general and specific character, diachronic approach, stylistics based on the relations between an author and a reader and some others. Discussing decoding stylistics, we must keep in mind its such important techniques as close reading, the role of intertextuality in proper text decoding, stylistic devices employed by the author as a means of encoding information and importance of reader-response theory.

Method: The article presents the results of the textual, stylistic, lexical, and contextual analyses of literary texts belonging to a very specific genre – sudden fiction. Stylistic analysis covers all the language level: phonetic, morphological, syntactic, and lexical; its results are widely illustrated by numerous examples from the texts under consideration. As far as short fragments from the text are extracted as illustrations of the different types of foregrounding, contextual analysis appears to be very helpful in explaining signals of addressee-orientation hidden by an author.

Originality: Comprehensive multi-aspect approach to the texts of sudden fiction provides a new perspective in text linguistics in general and decoding stylistics in particular. The author not only analyses the role of foregrounding and its types, but connects it with information theory, intertextuality, types of plot development, and text strong positions.

Result: Much attention in the study is paid to foregrounding as the basic notion of decoding stylistics as well as its types: coupling, convergence, semantic repetition, salient feature and text strong position, and defeated expectancy. Numerous examples vividly show which of these types are the most important in the texts of sudden fiction, how they are intertwined in the text, and with what purpose are used.

Conclusion: Though the hypothesis was that due to a specific genre of the considered texts, that is sudden fiction, the main types of foregrounding would be defeated expectancy, the results show that foregrounding in 152 texts of sudden fiction is realized mainly due to text salient feature, namely the title, the beginning and the ending of the text. Other very important types of foregrounding are convergence and defeated expectancy.

1. Introduction

Sudden fiction is celebrated for its ability to capture the essence of a story in a brief and potent form, making it well-suited for readers with limited time and attention spans. It challenges writers to distil their ideas to the purest form and offers readers a quick yet satisfying literary experience. As a popular literary genre, sudden fiction has been in the focus of linguists who examined its features (Abbasi, Al-Sharqi, 2016); types of plot development (Othman, 2023; Panasenko, 2017); semantics of colour terms (Panasenko, 2019); application of flash fiction in teaching reading and writing (Tarrayo, 2019). Now I intend to consider it from a different perspective. My aim is to make an interpretation of the texts written by English-speaking writers and to consider these texts from the point of view of decoding stylistics, which may be a good theoretical background for decoding the messages sent to the reader by the author and identify them as signals of addressee-orientation.

Traditionally, foregrounding includes coupling, convergence, semantic repetition, salient feature, and text strong position, together with defeated expectancy. My task is to specify their role in short stories by English-speaking writers. My hypothesis is that texts of sudden fiction are based on defeated expectancy, which is intensified by convergence and semantic repetition.

For my research, I have chosen 152 short stories and used textual, stylistic, lexical, and contextual analyses.

2. Stylistics and its types

Before proceeding to decoding stylistics, I would like to make a short retrospective journey into the history of stylistics and its types. If you try to find varieties of stylistics in different serious sources, you will be surprised how many can be found. In the alphabetic order the list from different sources looks like this: affective, applied, attributional, author’s, classical, cognitive, comparative, computational, contrastive, corpus, decoding, dialectal, encoding, expressive, forensic, formalism, functional, general, generative, genetic, historical, immanent, interpretative, linguostylistics, literary, practical, pragmatic, reader-response, reader’s, structuralist, stylistics of a national language, stylistics of effects, stylistics of intentions, stylometric (statistical), text (textual, textualist), and systemic functional stylistics (36).

In my opinion, all these types of stylistics can be sorted on some principles.

Firstly, some terms are synonyms, like genetic (author’s/reader’s) stylistics, text (textual/textualist) stylistics, decoding (reader-response) stylistics, etc.

Secondly, some of the types of stylistics are of general character (general, interpretative, linguostylistics, and literary), whereas the others are very specific, like, for instance, computational, which uses definite techniques for processing large corpora of works identifying the authorship and text stylistic elements; forensic, which also determines the authorship using traditional stylistic analysis, but is mainly applied in criminology or academic plagiarism cases; affective, which deals with the process of reading and the reader’s emotional and psychological response to it.

If we take into account a diachronic approach, we would definitely start with classical stylistics, which focuses on the study of literary texts from ancient Greece and Rome, examining their linguistic and stylistic features; scholars associated with classical stylistics include Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian (Burke, 2023). Subsequently, we would proceed to cognitive stylistics, which draws on insights from cognitive linguistics that appeared in the 1970s and psychology with the purpose to analyse the cognitive processes involved in the production and interpretation of literary texts. Scholars like Reuven Tsur, Peter Stockwell, and Vera Tobin have made important contributions to this field (see also Bretones et al., 2021; Ganieva, 2023; Semino and Culperer, 2002). Historical stylistics, focusing on the stylistic system of a language, is also connected with a diachronic aspect.

Another approach is associated with different scholars who have made significant contributions to the field.

Immanent stylistics (stylistics from a textual perspective) rests upon such basic concepts, as literary fact relativity principle, artistic image rejection, literariness, defamiliarization, distinction between plot and story, fusion of form and content, motivation, entire text partitioning, and some others. It is related to Russian Formalism, which developed in the early 20th century. Russian Formalism emphasizes the study of literary devices and the internal structure of texts. Prominent scholars in this field include Viktor Shklovsky, Roman Jakobson, and Boris Eichenbaum. It is also connected to French structuralism associated with scholars like Claude Levi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida; it examines the underlying structures and systems that govern language and literature. Structuralist approaches to stylistics often involve the analysis of narrative structures and the decoding of implicit meanings (Burke, Evers, 2023).

Functional stylistics was developed by the Prague School linguists, or the Prague Linguistic Circle, in the 1920s and 1930s. Such scholars as Jan Mukařovský, René Wellek, and Roman Jakobson contributed to the development of this field, which focuses on the communicative functions of language and the analysis of literary texts (Burke, 2025; Lin, 2016).

We cannot forget about systemic functional linguistics, developed by Michael Halliday, which focuses on the relationship between language and social context. Stylistic analysis within this type of stylistics examines how language functions in specific registers, genres, and social situations (Matthiessen, Teruya, 2023).

Linguostylistics and literary stylistics can be considered via the opposition of language and speech (Alaghbary, 2022; Jeffries, McIntyre, 2025).

The object-matter and research methods specify the type of linguistics: applied, comparative, contrastive, corpus, interpretative, practical, stylometric (statistical), and text (textual, textualist). I do not include into this list graphical stylistics and those types which are connected with different language levels: phonetic, morphological, lexical, and syntactic, though this classification is very popular and can be found in any textbook on stylistics, often named as stylistic phonetics, stylistic morphology, stylistic syntax, and stylistic semasiology.

Another group includes types of stylistics connected with the relations between an author and a reader, i.e. on the functional or pragmatic parameter. These are author’s, decoding, genetic, reader’s, and reader-response stylistics.

There are three basic points of view in genetic stylistics (stylistics of intentions, of effects): that of the addresser, the message, and the addressee. It covers the research of the author’s choice of speech forms, their message to the receiver and its realization, the main ideas and themes based on the author’s emotions, attitudes and views, the information (message) is coded uniquely according to the author’s choice. The encoder (writer) sends information to the recipient (addressee, reader) and the reader is supposed to decode the information.

Genetic stylistics is represented by a number of schools and trends: logical analysis of Marius Roustan, psychological analysis of Maurice Grammont, statistic stylistics of Pierre Guiraud, philological analysis of Leo Spitzer and Dumitru Caracostea. The aim of stylistic analysis is to bring out the writer’s intention to describe non-textual reality (extra-linguistic reality): writer’s biographical, social, economic, and political facts (Guiraud, 1969; Spitzer, 2015).

Now let us proceed to decoding stylistics and highlight its most important constituents.

2.1.Decoding stylistics and its basic features

Decoding stylistics, or stylistics of perception, refers to the analysis and interpretation of the underlying meanings and messages conveyed through the stylistic choices made by the author. It involves unravelling the various linguistic and literary devices to communicate the writer’s ideas and evoke specific responses from the reader. Using theoretical findings in several branches of science (informatics, mathematics, media studies, etc.), it overlaps with other types of stylistics and with information theory.

In the field of stylistics, scholars often use a range of techniques to decode and analyse literary texts. Here are a few common approaches:

Close reading. This technique involves carefully examining the language and literary devices used in a text to uncover its deeper meanings and thematic elements. It focuses on analysing the stylistic choices made by the author and how they contribute to the overall effect of the text (for more, see Tarrayo, 2019).

Intertextuality. Decoding stylistics also involves exploring the intertextual references and allusions employed by an author. By examining how a text refers to or quotes from other texts, scholars can better understand the intended meanings and connections that the author is making (for more, see Kryachkov, 2023).

Contextual analysis. It is essential to consider the social, historical, and cultural factors that shape the production and reception of a text. Analysing the sociocultural context surrounding a text can help decode the stylistic choices and understand the author’s intended meanings (for more, see Svensson, 2020).

Stylistic devices. Scholars examine the various literary devices of different language levels, tools, and techniques used by the author, such as metaphor, simile, alliteration, repetition, imagery, irony, and symbolism. These devices contribute to the overall aesthetic and communicative aspects of the text and can be decoded to reveal deeper layers of meaning (Kövecses, 2018; Panasenko, 2013).

Reader-response theory. Decoding stylistics can also involve considering the response and interpretation of the reader. The way readers engage with and interpret a text can influence the decoding process, as readers bring their own experiences and perspectives to the reading process (Widdowson, 1975). This approach is closely connected with pedagogy and information theory.

The author encodes his/her point of view using his/her own style, ideas, vocabulary, biography, etc. and sends it to the reader. Arnold (1990) who has considerably contributed to this type of stylistics offers the following scheme: code – message – sign – text. It is the shortened version of the information theory adjusted to linguistics. After Shannon (1998 [1940s]), the communications process over a discrete channel has 6 parts: 1) encoding the message; 2) its transmission; 3) its realization as a signal; 4) channel of receiving and transmission; 5) its reception; 6) its decoding.

Discussing the information theory applied to linguistics, it is important to keep in mind obstacles of decoding, which arise due to the level of the competence of the reader, who can be experienced or naïve; there may be social, historical, temporal, cultural, etc. hindrances to proper text understanding; many works of art are sophisticated in form and content, full of implications, contain understatements, and open-ended composition. Decoding stylistics helps the reader understand the author’s messages by explaining and decoding pieces of hidden information, which can be treated as signals of addressee-orientation, the detailed analysis of which in media texts is given by Panasenko et al. (2021).

Perception of the text can be enhanced by foregrounding, which, as Arnold (1990) specifies, is a self-explanatory term, because foregrounding assures the hierarchy of meanings with artistic value to be brought to the foreground. The scholar claims that the idea of foregrounding appeared first in the Prague School, where the phenomenon was mostly called the “deautomatization” of the linguistic code (Arnold, 1990; Kupchyshyna, Davydyuk, 2017).

Foregrounding refers to the deliberate manipulation of linguistic elements to draw attention to certain features, creating emphasis or deviation from the norm; it involves bringing certain linguistic features into prominence, making them stand out from the ordinary or expected usage. This can include deviations from the standard grammar, the use of unusual or striking vocabulary, and the application of rhetorical devices. Foregrounding serves various purposes, such as emphasizing key ideas, creating memorable language patterns, or evoking specific emotions in the reader or audience. It is a conscious choice by the writer to make certain aspects of language more noticeable.

Under the general heading of foregrounding Arnold (1990) includes the following phenomena: coupling, convergence, semantic repetition, salient feature and text strong position, and defeated expectancy. They differ from expressive means known as tropes and stylistic figures because they possess a generalizing force, function, and provide structural cohesion of the text and the hierarchy of its meanings and images, bringing some to the fore and shifting others to the background. They also enhance the aesthetic effect and memorability.

Let us discuss these types of foregrounding.

Coupling is associated with Samuel R. Levin and Roman Jakobson. Coupling is based on the affinity of elements and provides cohesion, consistency, and unity of the text form and content. There are several types of coupling: phonetic (alliteration and assonance; rhyme and rhythm mainly in poetry, though not only there), structural, and semantic.

Convergence is a combination or accumulation of stylistic devices promoting the same idea, emotion or motive; it helps decode the author’s message attracting the reader’s attention to text fragments abounding in stylistic devices of different levels – phonetic, morphological, syntactic, etc.; each of them performs a specific stylistic function. This term was first introduced by Riffaterre in 1959 (1959: 172).

Semantic repetition. Repetition is a natural language phenomenon; stylistics traditionally singles out repetition on the phonetic level and repetition on the syntactic level. Lessard and Levison (2013: 52) define semantic repetition as “the recurrence of elements of meaning, possibly in the absence of repeated formal elements”. Very often it leads to semantic satiation, i.e. a psychological phenomenon that occurs when a word or phrase loses its meaning due to repetitive exposure.

Salient feature and text strong position. Arnold (2014: 173) names this type of foregrounding as “a modification of the so-called ‘philological cycle’ described by one of the most widely known stylistic critics of the beginning of the 20th century Leo Spitzer”. The title, the prologue, the epigraph, the opening lines, and the ending always occupy a text strong position due to their great informative value. A salient feature proves “a convenient starting point for an analysis that is further continued on the basis of other types of foregrounding” (ibid.).

Defeated expectancy is also a type of foregrounding. It implies such a narrative technique where the author sets up certain expectations or anticipations in the reader’s mind, only to subvert or thwart those expectations later on in the story. This technique plays with the reader’s assumptions and creates tension or surprise by deviating from the anticipated outcome. It occurs when the story leads the reader to expect a particular resolution, plot twist (Panasenko, 2017), or character development, but then delivers something unexpected or contrary to those expectations. This can result in a range of effects, including irony, humour, suspense, or emotional impact (for more, see Davydyuk, 2012; 2013a; 2013b).

Authors may employ defeated expectancy for various reasons: surprise and suspense, subversion of tropes, characterization, and emotional impact. It may come up on any language level, but is mainly based on stylistic semasiology of expressive meaning and lexico-syntactical stylistic devices (pun, zeugma, paradox, oxymoron, irony, anti-climax, etc.).

3. Sudden fiction as a literary genre

Sudden fiction, also known as flash fiction or microfiction, refers to extremely short stories characterized by their brevity and concise storytelling. These narratives typically range from a few words to a few hundred words in length, often encompassing complete plots, character arcs, or thematic elements within a minimalistic structure.

Traditionally its varieties are connected with its size: minisaga – 50 words, dribble, or drabble, or microfiction – from 100 to under 300 words, short short story or flash fiction – up to around 1,000 words, sudden fiction – usually a little over 1000 words, new sudden fiction – up to 1,500 words (Abbasi and Al-Sharqi, 2016), short story – up to 7,500 words. It is a common approach, but I have to state that sudden fiction, as any other literary text, is not only the calculation of words. These texts have a deep context and a specific structure. Considering them from a decoding stylistics perspective considerably facilitates proper interpretation of the author’s message.

What are the key features of sudden fiction? Taking into account the number of words mentioned above, I start with conciseness, because sudden fiction relies on brevity, condensing a story’s essential elements into a compact form. Authors must convey meaning, portray characters, and communicate emotions efficiently, using only a limited word count. Then comes immediacy, because sudden fiction often plunges readers directly into the heart of the story, wasting no time on exposition or background information. The narrative may begin abruptly, engaging readers from the opening lines and maintaining a sense of urgency throughout. We must also keep in mind suggestiveness, because, due to their limited length, sudden fiction stories often leave much to the reader’s imagination. Authors may employ suggestive or ambiguous language, allowing readers to fill in the gaps and interpret the story’s meaning for themselves. Impact is also important, because, despite their brevity, sudden fiction stories aim to pack a punch, leaving a lasting impression on the reader. They may deliver unexpected twists, profound insights, or emotional resonance in a short span of time. The “suddenness” of the plot depends on the experimentation of the author (Othman, 2023), because sudden fiction encourages experimentation with narrative forms, structures, and styles. Authors may employ unconventional techniques, such as fragmented narratives, nonlinear storytelling, or minimalist prose, to achieve maximum impact within a limited space.

Each country has outstanding representatives of this genre, like Bolesław Prus, Franz Kafka, Yasunari Kawabata, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Daniil Kharms, and many, many others.

As my analysis of the text is based on English-speaking writers, I would like to name some of them, paying tribute to their literary activity in the alphabetical order: Russel Banx, Charles Baxter, Donald Barthelme, Hugh Behm-Steinberg, Lydia Davis, Amy Hempel, Tania Hershman, Joyce Carol Oates, Jamaica Kincaid, Grace Paley, Robert Shapard, George Saunders, Deb Olin Unferth, among others.

Sometimes it is difficult to interpret properly the author’s messages hidden in the text and we have to read it several times. The flash fiction “For Sale, Baby Shoes, Never Worn” attributed to Hemingway may have many interpretations, but negative feelings like sadness, disillusionment, grief, anxiety, etc. are very likely.

4. Discussion

The short stories which I have processed represent authors from different English-speaking countries: Australia, Canada, South Africa, United Kingdom (including England and Wales), and United States. A short biography of each author is given at the end of each book; in case the short story is written in another language, the language is specified, as is the name of the translator. Though some of the stories are incredibly interesting, I claim that making the stylistic analysis of the translated text fragments may lead to wrong conclusions due to specific features of languages with different structures (Slavic languages, Japanese, etc.).

The basic feature of decoding stylistics is foregrounding, which aims for delivering the author’s message to the reader. Taking into account the large number of the examples, I will present only some of them according to the types of foregrounding. All the examples are accompanied by the source in the abbreviated form, the name of the author, and the title of the story. To explain my argumentation of identifying one type of foregrounding or another, the short gist of the story is given when necessary.

Let us start with coupling. Several examples of coupling presented by parallel constructions can be found in the story by the Welsh writer Leslie Norris “Blackberries”: “He took a sheet from a cupboard on the wall and wrapped it about the child’s neck, tucking it into his collar. … He could see the bumps they made in the cloth. He moved his finger against the inner surface of the sheet and made a six with it, and then an eight. He liked those shapes. … He took the sheet off the child and flourished it hard before folding it and putting it on a shelf. He swept the back of the child’s neck with a small brush” (SFI, 1989: 40). More information about the contextual situation in this short story is given below, when defeated expectancy is discussed.

Rhythm as another variety of coupling can be found not only in poetry, but also when we come across the repetitive pattern of certain actions in the short story “On Hope” by Spencer Holst (SFI, 1989: 51-54), in which a trained monkey steals the royal jewellery three times, which a gipsy, her owner, returns to the royal family, understanding the seriousness of this crime. The largest stone in the necklace is named the Diamond of Hope making the link with the title. This rhythmicality is further enhanced by the three possible endings of the story offered by the author.

Foregrounding in the text “Important Things” by Barbara L. Greenberg is realized through parallel constructions and anaphoric repetitions, which make the text cohesive and rhythmical (“You tell your children”, “You say…”, “You offer…” (SF, 1986: 149-150). In fact, the whole text can be considered as suspense or delay: there are many conditions that children demand and “If you don't, they'll have to resort to torture” (SF, 1986: 150).

Convergence. In the short story “Love, Your Only Mother” by the American writer David Michael Kaplan, the author’s message is foregrounded by the combination of a text salient feature (the title, the beginning, and the ending of the text) and convergence. A woman left her husband; they are not divorced; they are not communicating directly; she sends her daughter postcards with beautiful landscapes from different places in the United States. The postcards find a girl at home, at the apartments she rented as a student, and finally in her own house where she lives with her husband. Each postcard is signed identically; it is the title of the story. The daughter marked the movement of her mother on the atlas: 63 postcards, 400 lines – “our life together”. The last paragraph abounds in

ordinary and anaphoric repetitions, emotively charged words, metaphors and similes: “But on summer evenings, when the windows are open to the dusk, I sometimes smell cities… wheat fields…oceans – strange smells from far away – all the places you've been to that I never will. I smell them as if they weren't pictures on a post-card, but real, as close as my outstretched hand. And sometimes in the middle of the night, I'll sit bolt upright, my husband instantly awake and frightened, asking. What is it? What is it? And I'll say, She's here, she's here, and I am terrified that you are. And he'll say, No, no, she's not, she'll never come back, and he'll hold me until my terror passes. She's not here, he says gently…; she's not – except you are, my strange and only mother: like a buoy in a fog, your voice, dear Mother, seems to come from everywhere”. (SFI, 1989: 85-88).

Another good example of convergence can be found in the short story “The King of Jazz” by Donald Barthelme. It is a very specific story about a battle of jazz musicians: American and Japanese trombone players. Their way of playing is described metaphorically, using colours: “Playing with lots of rays coming out of it, some red rays, some blue rays, some green rays, some green stemming from a violet center, some olive stemming from a tan center –” (SF, 1986: 11). Sustained metaphors are concentrated in the very large paragraph of 13 lines at the end, characterizing the way an American trombone player (who won and became the King of Jazz again) was extracting sounds from his musical instrument: “You mean that sound that sounds like the cutting edge of life? That sounds like polar bears crossing Arctic ice pans? That sounds like a herd of musk ox in full flight? That sounds like male walruses diving to the bottom of the sea? … That sounds like the wild turkey walking through the deep, soft forest? … That sounds like a mule deer wandering a montane of the Sierra Nevada? … That sounds like –” (SF, 1986: 12-13). This paragraph also contains tautology, parallel constructions, anaphoras (syntactic stylistic devices) and onomatopoeia (phonetic stylistic device).

Semantic repetition. The title of the short story by Stuart Dybek “Death of the Right Fielder” (SFI, 1989: 35-38) as a salient feature is enhanced by semantic repetition. The word ‘death’ and words of the same lexico-semantic field (to kill, a terrorist, a mad sniper, to pull the trigger, a bullet, shooting, a fresh grave, and epitaph), in fact, lose their meaning, because, notwithstanding their repeatability, they lead to nothing, and it is still not clear at the end of the text who killed the baseball player.

In many texts, various types of foregrounding enhance each other, like in the short story “The cliff” by Charles Baxter. Semantic repetition can be found in the signals of addressee-orientation denoting different shades of a blue colour: “the long line of blue water”, “faded blue jeans”, “the boy’s blue eyes”, “the sea”, and “the blue sky” (SF, 1986: 43-46). This colour intensifies features of a 15-year-old innocent teenager, because blue has a symbolic meaning of innocence. The events take place near the sea (blue is a typical colour of the sea and the sky). Blue is also associated with magic and it happens. After some magic rituals, the boy steps off the cliff and starts flowing “in great soaring circles”. This magic, in our case culminating in defeated expectancy, is foregrounded by the title and symbolic meaning of a blue colour.

Salient feature and text strong position. Foregrounding in the short story “The Weather in San Francisco” by Richard Brautigan is vividly realized by a salient feature and a text strong position, i.e. the title is connected with the first paragraph: “It was a cloudy afternoon with an Italian butcher selling a pound of meat to a very old woman, but who knows what such an old woman could possibly use a pound of meat for?” (SFI, 1989: 119). Here the message of the author is quite clear, because the reader comes to know about the protagonists of this story (a butcher and a very old woman), the event (buying meat), and the reason of buying meat (“Perhaps she used it for a bee hive and she had five hundred golden bees at home waiting for the meat, their bodies stuffed with honey”, ibid.). The customer and the seller discuss weather while choosing a specific sort of meat. Though this signal of addressee-orientation is very strong, anyone hardly believes that the liver is bought for the bees, thus, the stronger the effect of the defeated expectancy is. The ending of the text (again, a text strong position) includes many stylistic devices: “She opened her purse which was like a small autumn field and near the fallen branches of an old apple tree, she found her keys” (simile); “Then she opened the door. It was a dear and trusted friend” (personification); “She nodded at the door and went into the house and walked in a long hall into a room that was filled with bees” (defeated expectancy). Convergency is formed due to anaphoras and parallel constructions: “There were bees everywhere in the room. Bees on the chairs. Bees on the photograph of her dead parents. Bees on the curtains. Bees on an ancient radio that once listened to the 1930s. Bees on her comb and brush” (SFI, 1989: 120). The author brilliantly connects the last paragraph with the title of the story: “The bees came to her and gathered about her lovingly while she unwrapped the liver and placed it upon a cloudy silver platter that soon changed into a sunny day” (SFI, 1989: 120).

Ann Beattie, the author of the short story “Snow”, sends many messages to the reader in the text: a snowy winter is not a perfect period of courting and love; the snow is not eternal and melts bringing changes, another season of the year or new love; white colour is a symbol of innocence. The title, occupying a text strong position, highlights many words and word combinations forming a special lexico-semantic group: “the big snow”, “like a crazy king of snow”, “kneeling in snow”, “all that whiteness”, “the newly fallen snow”, “the cold”, “winter”, “snowplow”, “scraping snow”, etc. (SFI, 1989: 286-288); each element of this group has a different function: descriptive, associative, and symbolic (for more see Panasenko 2019: 136).

The title of the short story “Even Greenland” by Barry Hannah is based on paradox: Greenland is not green. A pilot says: “Even Greenland. It’s fresh, but it’s not fresh. There are footsteps in the snow” (SF, 1986: 8). And the flight is not flight: it is falling down of the airplane with its further explosion, which is described metaphorically: “The wings were turning red. I guess you’d call it red. It was a shade against dark blue that was mystical flamingo, very spacey like, like living blood. Was the plane bleeding?” (SF, 1986: 7).

George Garrett in the short story “The Strong Man” describes a pregnant young woman who intends to divorce her unfaithful husband and who stays together with her lover in Italy. She faces many problems and sees no solution to them. To entertain her, Harry, her lover, offers to watch a street performance. The tricks performed by an actor, whom everybody called a strong man, were gradually becoming more and more complicated; finally, he was covered by chains. The young woman “watched the man in chains and she felt a strange exhilaration. She felt her own body move, tense with the subtle rhythm of his struggle. One arm free, then, slowly, very slowly, the other, and, at last sitting up, he twisted his hurt legs free” (SF, 1986: 148). The message of liberation through sufferings and great efforts is foregrounded by the title. The very last paragraph constitutes a text salient feature, because symbols of new life, strength, and serenity appear in the heart of the young woman: “… she saw that there was a new moon and she could see the dark shape of the mountains. They were still there. And she could feel the strength and flow of the river, and she could feel her child, the secret life struggling in her womb” (SF, 1986: 148).

One more interesting feature should be mentioned. The foregrounding in this text is enhanced by suspense (Brewer, 1996). For the woman it is mainly emotional tension, whereas for the strong man it is a physical restraint. Following the strong man’s efforts, a woman shares his tension and finally, simultaneously with the street actor, feels total relaxation.

Some titles used as foregrounding demand the possession of specific knowledge, otherwise the author’s message will not be decoded properly. The short story “Tent Worms” by Tennessee Williams has deep context. A husband and his wife rented a house for summer but it was surrounded by “the tent worms that were building great, sagging canopies of transparent gray tissue among the thickly grown berry trees” (SF, 1986: 96). These silvery nets were covered by numerous tent caterpillars, which totally defoliated trees. Billy Foxworth did his utmost to save poor trees burning these nets out with paper torches “childishly, senselessly, in spite of the fact that there were thousands of them” (ibid., 97), but he ran out of paper and matches and “had a defeated look and he had burned himself in several places”. From the talk of his wife Clara and a Doctor we come to know that Billy is lethally ill and his wife realizes that he knows about it. He has given up burning tent worms and they both know that “they, no, would never return, separately or together” (ibid., 100) to this place. Billy Foxworth is doomed, nothing will help him and his failure in burning the worms vividly indicates it.

Interesting examples of the titles which foreground the author’s message are in “A Walled Garden” by Peter Taylor (SF, 1986: 58-61) – isolation and seclusion (“We’ve walled ourselves in here with these evergreens and box and jasmine” (ibid., 58); garden can also be considered as a linguistic cultural symbol (Karasik 2023); “Tickits” by Paul Milenski (SF, 1986: 155-157) – characterizing the pronunciation and spelling of the notes Toby Heckler prepared for any case, which attracted his attention; his notes are written in capital letters (“PRAKING MISTEAK”, “PAPUR ON GARSS”, “TOO MUSH DIRNKING”, “ERVYTHING WORNG!”), etc.

Epigraphs are very scarce in this literary genre. They are used for specific purposes, such as explaining the text, like in the short story “Seven Pieces of Severance” by Robert Olen Butler (NSF, 2007: 131-136):

“After careful study and due deliberation it is my opinion

the head remains conscious for one minute and a half after decapitation.

Dr. Dassy d’Estaing, 1883”

“In a heightened state of emotion, we speak at the rate of

160 words per minute. Dr. Emily Reasoner, A Sourcebook of Speech, 1975”

My students made special research and found out that these names are fictitious as well as the information presented in the epigraphs. A Sourcebook of Speech from this date never existed. But these epigraphs are very important, because they foreground the meaning of the whole text, which consists of seven short fragments without punctuation marks, like a stream of consciousness of people who were decapitated. Some of these people were real, like Paul the Apostle, the exact details of whose death are unknown, or Angry Eyes, an Apache warrior, or “Hanadi Tayseer Jaradat, law student, beheaded by self-detonation of shaheed-belt suicide bomb, 2003”; some alleged to be common people, like “Rokhel Pogorelsky, Jewish woman, beheaded in Russian pogrom, 1905”, but again in some cases it was not historically accurate. Without these two epigraphs, the message of the author would have been totally lost: “breechcloth and moccasins only these things on my body my head bound by a cloth band my face and chest and arms stained but I do not know the colors I do not look, my eyes are fixed on the horizon beyond mesquite and pinon and…” (paragraph “Angry Eyes”, NSF, 2007: 135).

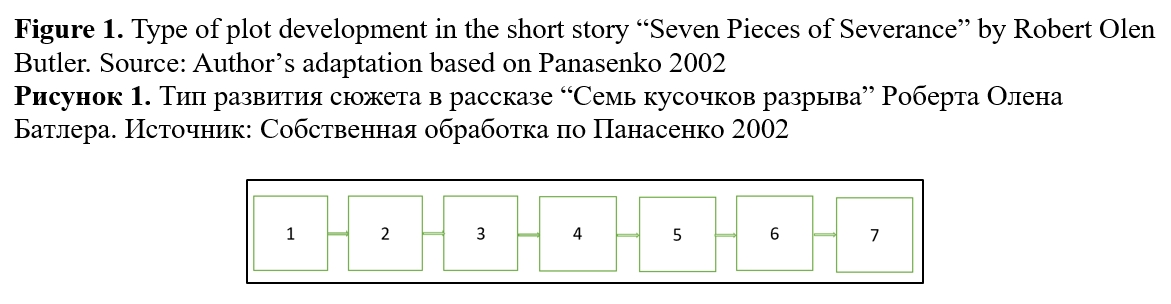

It is important to mention the type of plot development in this text. Panasenko (2002; 2017: 110) offered four basic types of plot development: a chain, a ring, a fan, and a circle. Later this classification was enlarged by various combinations of these basic models. In this short story, it is obviously a chain, in which we see the description of seven events (see Figure 1).

Epigraphs can also be found in the short stories “I Shot the Sheriff” by Touré (NSF, 2007: 159-163), “The Gold Lunch” by Ron Carlson (NSF, 2007: 281-287), “Twirler” by Jane Martin (SF, 1986: 17-19), “The Artichoke” by Marilyn Krysl (SF, 1986: 217-218) and in some short stories written by non-English-speaking writers.

Discussing defeated expectancy, I should state that its (un)predictability depends on the context. Every woman knows that blackberries leave indelible spots on fabric. Thus, the use of a new cap as a container for blackberries with inevitable results is predictable to evoke the irritation of the boy’s mother. The father, perhaps, knew nothing about it and his deed brought the situation to the family scandal (Leslie Norris “Blackberries”, SFI, 1989: 39-44).

The phrase “Thank You, M’am” is not only the title of a short story by Langston Hughes; it is the salient feature that ends this story. A young boy is caught stealing her purse by Mrs. Jones. The defeated expectancy is also foregrounded by this phrase: instead of taking the boy to the police, the old lady gives him some food and money to buy “some blue suede shoes” (SF, 1986: 67).

Interesting examples of defeated expectancy as a type of foregrounding can be found in the following short stories: “Sunday in the Park” by Bel Kaufman (SF, 1986: 20-23); “Song on Royal Street” by Richard Blessing (SF, 1986: 29-32); “Pygmalion” by John Updike (SF, 1986: 33-35); “The Hatchet Man in the Lighthouse” by William Peden (SF, 1986: 109-111); “The Quail” by Rolf Yngve (SF, 1986: 109-213); “Sleepy Time Gal” by Gary Gildner; “The Bank Robbery” by Steven Schutzman (SF, 1986: 94-95), in which the robber is in intensive written correspondence with the teller and finally they leave the bank together carrying the stolen money; “Dog Life” by Mark Strand, where a husband confesses to his wife that he was a dog and gives details of his courting “a melancholic Irish setter, …a long-coated Chihuahua and black and white Papillon, … a German short-haired pointer” (SF, 1986: 107); “Thief” by Robley Wilson, Jr., in which a man robbed at the airport was accused of stealing his own wallet with an ID, because, on his request, the thief gave him back somebody else’s wallet. The poor man can’t prove his identity and innocence to the policeman. Great scandal. In two weeks, he receives his wallet back, “no money is missing, all the cards are in place” (SF, 1986: 171).

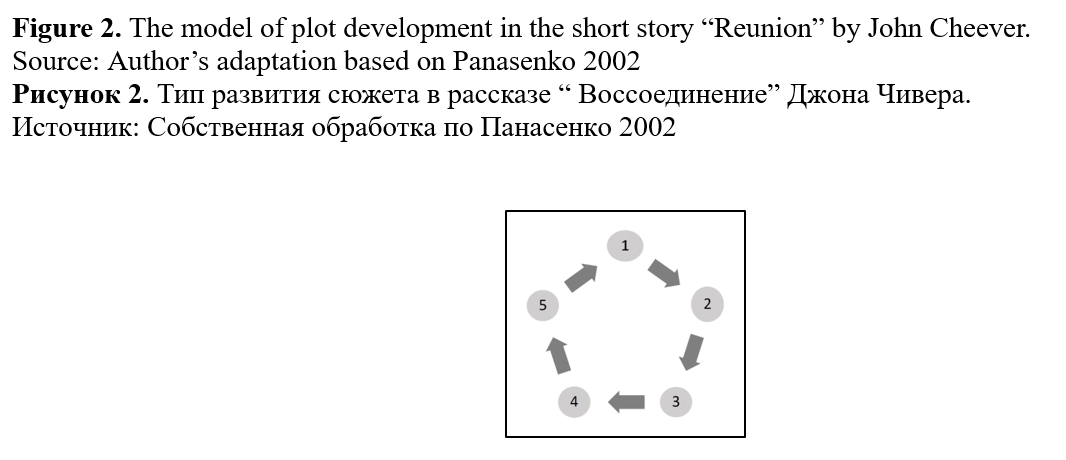

The message of the author can be foregrounded by specific plot development, as, e.g., in the short story “Reunion” by John Cheever. A young man is eager to meet his father for the first time in three years after his parents’ divorce. As he has only an hour and a half, his father invites him for lunch next to a railway station. The young man was so glad to meet his father; he even expected that “someone would see us together. I wished that we could be photographed. I wanted some record of our having been together” (SF, 1986: 14). They visited four restaurants but each time it was a failure, because his father caused a scandal everywhere. Even when he wanted to buy a paper to read on the train for his son at a newsstand, it was not a success. The events start and end at the railway station. I can present the plot development of this short story as a ring of closed rings (see Figure 2).

Each event ending with a scandal is completed. The protagonists return to the starting point of their meeting. Taking into account that the ring is closed, it shows no prospect of their communication in future. It is proved by the very last sentence (text strong position): “Goodbye, Daddy,” I said, and I went down the stairs and got my train, and that was the last time I saw my father” (SF, 1986: 16). Then the title of the text “Reunion” sounds ironic and sarcastic.

Foregrounding in the short story “Turning” by Lynda Sexson (SF, 1986: 70-73) is based on intertextuality. Robert, a four-year old child is visited on his birthday by three elderly ladies whom he calls Louise Dear, Olivia Sweet, and Ruth Love. After the birthday cake, they take turns narrating an extremely bizarre tale. They invent stories about “The Emperor Who Had No Skin”. In fact, these stories form a fairy tale with its such obligatory elements, as a prince/emperor, princesses, tasks to complete, and a sacred number three. The prince gives three tasks to his potential brides according to the rules of any fairy tale; these three stories form the recognizable pattern "text in a text", i.e. intertextuality. Physical outlook of the prince and unusual tasks he gives to young women are foregrounded by defeated expectancy.

Three old women together with a little boy invent stories where each ending of the fairy tale leads the reader to surprise, i.e. defeated expectancy.

If in the short story “Tent Worms” by Tennessee Williams mentioned above the message of the author is clear to those who know at least something about the tent worms, the short story “The Rememberer” by Aimee Bender (NSF, 2007: 63-67) needs a thorough comprehensive reading. Let us pay attention to different types of foregrounding in it and try to decode the signals of addressee-orientation in this text. The “rememberer” means a person who remembers several words and phrases from an endangered or moribund language but never becomes fluent in it, because it is difficult to find an interlocutor. In sociolinguistics, it is a person who recalls something from memory. Who is the rememberer in this narrative? Annie tells us a story about her lover Ben who at first changed into “some kind of ape”. It can be taken for allegory or metaphor, but his reverse evolution continues: a sea turtle, then a salamander. Through the whole text the heroine repeats the word “to remember” and “memories” related to it (a case of semantic repetition); she worries if Ben being in a different shape still remembers her and if he remembers where to find her house in case he comes back in a human body.

At the very beginning of the text (its salient feature), the whole gist is rendered in as few as one paragraph: “My lover is experiencing reverse evolution. I tell no one. I don’t know how it happened, only that one day he was my lover and the next he was some kind of ape. It’s been a month and now he’s a sea turtle” (NSF, 2007: 63).

Examples of convergence and coupling are found at the end of the text: “This is the limit of my limits: here it is. You don’t ever know for sure where it is and then you bump against it and bam, you’re there. Because I cannot bear to look down into the water and not be able to find him at all, to search the tiny clear waves with a microscope lens and to locate my lover, the one-celled wonder, bloated and bordered, brainless, benign, heading clear and small like an eye-floater into nothingness” (NSF, 2007: 66). Here we also see tautology (the limit of my limits) and alliteration. Galperin describes alliteration as “a phonetic stylistic device which aims at imparting a melodic effect to an utterance. The essence of this device lies in the repetition of similar sounds, in particular consonant sounds, in close succession, particularly at the beginning of successive words” (Galperin, 1971: 121).

Let us consider the words starting with ‘b’, which I marked in bold, from the point of view of phonosemantics. Interesting examples of the meanings of different sounds can be found in “A Dictionary of English Sound” by Magnus (s.a.), who names sounds or sound sequences and their associated meanings as phonesthemes. She "presents the phonesthemic classification of the most common monosyllabic words in English and shows which associations they evoke" (Panasenko, Mudrochová, 2021: 431). We applied her classification to the advertisement's text analysis and chose suitable meanings of /b/. As it comes from the analysis of the example above, it is obvious that /b/ is associated with water, barriers, interference, emptiness, binding, contact, connection, departure, birth and beginnings, and some other things. Most of these meanings that can be found in this extract and are connected with the whole story.

5. Conclusion

In my textual analysis, different approaches popular in decoding stylistics have been used, the major ones being: close reading, which allows to deeply penetrate into the meaning of the text and the choice of the stylistic devices; intertextuality, i.e. text in a text presenting quotations and allusions to famous pieces of art, culture, and literature; contextual analysis, based on social-cultural, historical, and other types of contexts; stylistic analysis, covering all language levels.

In the process of sudden fiction analysis through the lens of decoding stylistics, we cannot ignore other types of stylistics. In some texts, we must take into account both the suspense and the readers’ emotional response to it, i.e. the domain of affective stylistics. Convergence is based on the interrelation of the stylistic devices belonging to different language levels – the object-matter of literary stylistics – phonetic (rhythm, onomatopoeia, alliteration, etc.); lexical (metaphor, epithet, personification, etc.), and syntactic (repetition, inversion, polysyndeton, etc.).

It is hardly possible to make any calculation while analysing texts of sudden fiction, though it is obvious that coupling and semantic repetition are not as widely employed by the authors as the other types of foregrounding. Each text has a unique structure, combines various types of foregrounding enhanced by intertextuality, curves of plot development, and suspense.

Out of the numerous types of stylistics, I have chosen decoding stylistics for interpreting sudden fiction texts, because it involves analysing the stylistic choices made by a writer, while foregrounding specifically looks at intentional highlighting or deviation from the ordinary in linguistic elements. Foregrounding is a key aspect of stylistic analysis, helping readers uncover the nuances and artistic dimensions of language use in texts.

Decoding stylistics is equally strongly connected with information theory, i.e. the continuum “code – message – sign – text”. Foregrounding may be considered as an important tool of extracting the signals of addressee-orientation encoded by the author from the text.

Taking into account the specificity of this literary genre, my hypothesis was that defeated expectancy would prevail among the other types of foregrounding. However, my research findings suggest that defeated expectancy plays a less crucial role in sudden fiction texts. The results of my research show that foregrounding in sudden fiction is realized by coupling, convergence, semantic repetition, text salient feature and strong positions, and defeated expectancy. I would give priority to the text salient feature, namely the title, the beginning, and the ending of the text. It is the title, which sends a very important message to the reader and lays the foundation of proper text understanding. Convergence, ranking second, can often be found in concluding paragraphs. Defeated expectancy, taking third place, is often intensified by the title and other types of foregrounding. Though my hypothesis was not justified, defeated expectancy can be considered as a very important signal of addressee-orientation highlighting the features that are of utter importance for proper decoding.

Reference lists

Abbasi, I. and Al-Sharqi, L. (2016). Merging of the Short-Story Genres, Studies in Literature and Language, 13, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3968/7962(In English)

Alaghbary, S. G. (2022). [e-version 2024]. Introducing Stylistic Analysis: Practising the Basics, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK. (In English)

Arnold, I. V. (2014). Paradigma antropotsentrizma, pragmalingvistika i stilistika dekodirovaniya. Semantika. Stilistika. Intertekstual'nost' [Paradigm of anthropocentricity, pragmalinguistics and decoding stylistics. Semantics. Stylistics. Intertextuality], URSS, Moscow, Russia, 172–183. (In Russian)

Arnold, I. V. (1990). Stilistika sovremennogo angliyskogo yazyka: stilistika dekodirovaniya [Stylistics of Modern English: Decoding Stylistics], Prosveshcheniye, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Bretones, C., Ridao, S. and Alarcón, S. (2021). Language, Cognition and Style: An Introduction to the Cognitive Stylistics Section, Odisea, 22, 9–13. DOI: 10.25115/odisea.v0i22.7151 (In English)

Brewer, W. F. (1996). The Nature of Narrative Suspense and the Problem of Rereading, in Vorderer, P., Wulff, H. J., Friedrichsen, M. (eds.). Suspense: Conceptualizations, Theoretical Analyses, and Empirical Explorations, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah (NJ), USA, 107–127. (In English)

Burke, M. (2023). Introduction Stylistics: From Classical Rhetoric to Cognitive Neuroscience, in Burke, M. (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Stylistics, 2nd ed., Routledge, London, 1–8. (In English)

Burke, M. (2025). Marking the Stylist from the Style, in Burke, M. and Gavins, J. (eds.). Style as Motivated Choice: In memory of Peter Verdonk (1934-2021), John Benjamins, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1–5. (In English)

Burke, M. and Evers, K. (2023). Formalist Stylistics, in Burke, M. (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Stylistics, 2nd ed., Routledge, London, UK, 32–45. (In English)

Davydyuk, Yu. (2013a). Defeated Expectancy as a Mental Space Phenomenon, International English Studies Journal. Studia Anglica Resoviensia, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego, Rzeszów, Poland, 10, 7–15. (In English)

Davydyuk, Yu. (2013b). Defeated Expectancy in the Semantic Structure of the Literary Text, in Science and Education: A New Dimension, Philology, Budapest, I (2), 11, 46–51. (In English)

Davydyuk, Yu. (2012). The Effect of Defeated Expectancy from the Point of View of Decoding Stylistics, in Lančarič, D. (ed.). Interdisciplinary Aspects of Language Study, Kernberg Publishing, Davle, 17–26. (In English)

Galperin, I. R. (1971). Stylistics, Higher School Publishing House, Moscow, Russia. (In English)

Ganieva, Z. M. (2023). The Development of Cognitive Stylistics, Galaxy International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 11 (1), 196–199. (In English)

Guiraud, P. (1969). Essais de stylistique, Éditions Klincksieck, Paris, France. (In French)

Jeffries, L. and McIntyre, D. (2025). Stylistics, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. (In English)

Karasik, V. (2023). Garden as a linguistic cultural symbol, in Lege artis. Language yesterday, today, tomorrow, University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Trnava, Slovakia, VIII (1), Special issue, 46–61. https://doi.org/10.34135/lartis.23.8.1.04(In English)

Kövecses, Z. (2018). Metaphor in Media Language and Cognition: A Perspective from Conceptual Metaphor Theory, Lege Artis. Language Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow, De Gruyter Open, Warsaw, Poland, III (1), June 2018, 124–141. DOI: 10.2478/lart-2018-0004 (In English)

Kupchyshyna, Yu. and Davydyuk, Yu. (2017). From Defamiliarization to Foregrounding and Defeated Expectancy: Linguo-stylistic and Cognitive Sketch, Lege Artis. Language Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow, De Gruyter Open, Warsaw, Poland, II (2), December 2017, 148–184. DOI: 10.1515/lart-2017-0015 (In English)

Kryachkov, D. (2023). Intertextuality in Media Texts, Lege Artis. Language Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow, University of SS Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Trnava, Slovakia, VIII (1), Special issue, 62–78. DOI: 10.34135/lartis.23.8.1.05 (In English)

Lessard, G. and Levison, M. (2013). Groundhog DAG: Representing Semantic Repetition in Literary Narratives. Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature, Association for Computational Linguistics, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 52–60. (In English)

Lin, B. (2016). Functional Stylistics, in Sotirova, V. (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Stylistics, Bloomsbury, London, UK. (In English)

Magnus, M. (s.a.). Sound Symbolism, Phonosemantics, Phonetic Symbolism, Mimologics, Iconism, Cratylus Ideophones, Synaesthesia, the Alphabet, the Word [Online], available at: http://www.trismegistos.com (accessed 25.10.2024). (In English)

Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. and Teruya, K. (2023). Systemic Functional Linguistics: A Complete Guide, Routledge, London, UK. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315675718(In English)

Othman, A. (2023). Plot in Flash Fiction: A Study of Irony in the Flashes in Lydia Davis’ Varieties of Disturbance (2007), International Journal of Arabic-English Studies, 23 (1), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.33806/ijaes2000.23.1.7(In English)

Panasenko, N. (2019). Colour terms in Sudden fiction, Linguistics & Polyglot Studies, 19 (3), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.24833/2410-2423-2019-3-19-131-138 (In English)

Panasenko, N. Types of Plot Development in Sudden Fiction (2017). Kryachkov, D. A. (ed.). The Magic of Innovation: New Dimensions in Linguistics and Linguo-didactics: A Collection of Research Papers, Vol. 1, Moscow State Institute of Foreign Relations (MGIMO University), Moscow, Russia, 107–114. (In English)

Panasenko, N. (2013). The Role of Syntactic Stylistic Means in Expressing the Emotion Term LOVE, Research in Language. The Journal of University of Lodz, Walter De Gruyter, Berlin, Germany, 11 (3) (Sep. 2013), 277–293. DOI: 10.2478/v10015-012-0016-6 (In English)

Panasenko, N., Krajčovič, P. and Stashko, H. (2021). Hard News Revisited: A Case Study of Various Approaches to the Incident at the Primary School Reflected in the Media, Communication today, 12 (1), 112–128. (In English)

Panasenko, N. and Mudrochová, R. (2021). Advertisement text as semiotic construal, Proceedings from the International Scientific Conference “Megatrends and media 2021: Home officetainment” held online on the 21st of April 2021, Faculty of Mass Media Communication, Trnava, Slovakia, 421–438. (In English)

Panasenko, N. I. (2002). Models of a Facetious Song Plot Development, Linhvistychnistudiyi [Linguisticsketches], 4, Vydavnytstvo Cherkas'koho Derzhavnoho Universitetu, Cherkasy, 40–52. (In Russian)

Riffaterre, M. (1959). Criteria for Style Analysis, Word, 151, 154–174.

Semino, E. and Culpeper, J. (2002) (eds.). Cognitive Stylistics. Language and Cognition in Text Analysis, John Benjamins, Amsterdam – Philadelphia. (In English)

Shannon, C. E. (1998 [1940s]). The Mathematical Theory of Communication, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, USA. (In English)

Spitzer, L. (2015). Linguistics and Literary History: Essays in Stylistics, Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA. (In English)

Svensson, L. (2020). Contextual Analysis: A Research Methodology and Research Approach, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Göteborg, Sweden. (In English)

Tarrayo, V. (2019). What’s in a Flash?: Teaching Reading and Writing (and beyond) through Flash Fiction, English Language Teaching and Research Journal (ELTAR-J). https://doi.org/10.33474/ELTAR-J.V1I1.4773(In English)

Widdowson, H. G. (1975). Stylistics and the Teaching of Literature, Longman, London, UK. (In English)

Corpus Material

NSF, 2007 – Shapard, R. and Thomas, J. (eds.; 2007). New Sudden Fiction Short-Short Stories from America and beyond, W. W. Norton and Company, New York – London.

SF, 1986 – Shapard, R. and Thomas, J. (eds.; 1986). Sudden Fiction. American Short-Short Stories, Gibbs M. Smith Publisher, Salt Lake City.

SFI, 1989 – Shapard, R., Thomas, J. (eds.). (1989). Sudden Fiction International.SixtyShort-Short Stories, W. W. Norton and Company, New York – London.