Revealing Cultural Meaning with Trilingual Embeddings: A New Audit of LLM Multilingual Behavior

Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly regarded as authoritative mediators of multilingual meaning; however, their ability to preserve culturally grounded lexical distinctions remains uncertain. This issue is especially critical for the core lexicon – high-frequency, culturally salient words that constitute the conceptual foundation of linguistic cognition within a community. If these foundational meanings are distorted, the resulting semantic shifts can propagate through downstream tasks, interpretations, and educational applications. Despite this risk, robust methods for evaluating LLM fidelity to culturally embedded lexical semantics remain largely undeveloped. This editorial introduces a novel diagnostic approach based on trilingual aligned word embeddings for Russian, Lingala, and French. By aligning embeddings into a shared distributional space, we obtain an independent semantic reference that preserves the internal structure of each language. French serves as a high-resource pivot, enabling comparisons without forcing the low-resource language into direct competition with English or Russian embedding geometries.

We examine several culturally central lexical items – including kinship and evaluative terms – to illustrate how an aligned manifold can reveal potential points of semantic tension between LLM outputs and corpus-grounded meanings. While our case studies do not claim to expose fully systematic biases, they demonstrate how the proposed framework can uncover subtle discrepancies in meaning representation and guide a more comprehensive investigation.

We argue that embedding-based diagnostics provide a promising foundation for auditing the behavior of multilingual LLMs, particularly for low-resource languages whose semantic categories risk being subsumed under English-centric abstractions. This work outlines a research trajectory rather than a completed map and calls for deeper, community-centered efforts to safeguard linguistic and cultural specificity in the age of generative AI.

Keywords: Large Language Models, Trilingual Embeddings, Cultural Semantics, Low-Resource Languages, Multilingual NLP, Semantic Drift, Cross-Lingual Alignment, Linguistic Cognition, Multilingual AI Audit, Distributional Semantics

1. Introduction

Over recent years, large language models have transitioned from experimental tools to ubiquitous instruments utilized in communication, translation, and knowledge production. These models compose school essays and literature reviews, facilitate multilingual conversations, and increasingly serve as intermediaries among linguistic communities (Litvinova et al., 2024). Consequently, large language models (LLMs) occupy a role unprecedented by earlier technologies: they not only process text but also influence our understanding of linguistic meaning.

This transition has brought remarkable convenience; however, it has also introduced an epistemic risk that remains insufficiently addressed. Apparent fluency and coherence can obscure subtle distortions in meaning representation across linguistic systems – particularly when the target languages are structurally distant from English or underrepresented in the training datasets. In other words, fluency has become a veil that conceals underlying conceptual asymmetries.

This issue becomes particularly pronounced when addressing low-resource languages, such as the numerous Bantu languages spoken throughout Central and Southern Africa. These languages are not merely smaller variants of widely spoken global languages; rather, they embody unique relational structures, kinship systems, social norms, and conceptual metaphors. Their lexical items often encompass broader semantic domains than their English equivalents, and their core lexicon reflects cultural logics that remain opaque to non-native speakers. When large language models (LLMs) reduce these distinctions to English-centric categories, they do more than misinterpret individual words – they fundamentally disrupt the conceptual framework inherent to the language itself (Bird, 2020).

Multilingual evaluation in artificial intelligence has predominantly focused on benchmark performance metrics rather than on preserving semantic integrity. Although translation quality, factual accuracy, and syntactic well-formedness may seem adequate, deeper layers of cultural meaning are often neglected. The field still lacks robust, transparent, and culturally sensitive methodologies to detect instances where models impose English-centric conceptual frameworks onto low-resource languages.

This editorial presents a preliminary advancement in the development of such tools. We introduce a trilingual aligned embedding space constructed from Russian, Lingala, and French, designed to examine meaning not through prompt-based interpretations but via the distributional geometry inherent in each language as manifested in authentic corpora. French serves as a pivot, stabilizing the alignment and facilitating interaction between Russian and Lingala within a neutral semantic field, thereby avoiding mediation through English. Within this space, words organize into clusters, gradients, and oppositions that more accurately reflect lived linguistic practices rather than generative approximations.

An examination of Lingala terms such as mwana or malamu within this multifaceted framework immediately reveals patterns that LLMs fail to preserve. While the embedding space demonstrates complex, multi-layered relational fields, LLMs tend to provide limited glosses. Furthermore, whereas the corpus geometry uncovers culturally grounded evaluations, LLMs produce universalized abstractions shaped predominantly by English. These discrepancies are not deficiencies of the models themselves; rather, they result from training pipelines that prioritize high-resource languages and of architectures designed to optimize generalization rather than cultural specificity.

The issue at hand extends beyond simple computational fairness. Low-resource languages often serve as the primary repositories of community memory, identity, kinship structures, oral traditions, and social intuition. The reduction of their conceptual frameworks within global artificial intelligence systems leads to significant loss: these communities are not only underrepresented but also misrepresented (Blasi et al., 2022; Joshi et al., 2020).

Supporting low-resource languages involves more than simply including them in training datasets or broadening a model’s range of supported languages. It requires approaches that respect their intrinsic semantic structures, preserve culturally specific distinctions, and identify instances where large-scale models unintentionally replace these languages with homogenized, globalized conceptual frameworks.

The approach examined here – embedding-based semantic diagnostics – does not provide a comprehensive solution; however, it offers a crucial resource urgently needed by the field: an independent, culturally grounded benchmark for evaluating the behavior of LLMs. This method allows for the examination of meaning not only as described by the LLM but also as inherently structured by the language itself.

Our objective, therefore, is not to critique LLMs but to enhance the epistemic resources available to researchers, developers, and linguistic communities. Through this effort, we aim to promote a broader transition toward multilingual artificial intelligence that is not only technically advanced but also culturally responsible – AI that recognizes the semantic complexity of all languages, rather than solely focusing on those with extensive digital representations.

2. Why Cultural Meaning Matters More Than Ever

The rapid expansion of multilingual artificial intelligence has created a paradox regarding linguistic visibility. While an unprecedented number of languages are now represented in digital interfaces, translation systems, and conversational agents (Qin et al, 2025), the cultural essence embedded within these languages – comprising conceptual frameworks, relational categories, evaluative practices, and social distinctions that shape community worldviews – is at risk of gradual erosion. Although multilingual AI has the potential to enhance universal accessibility, it simultaneously poses the threat of universal simplification (Farina & Lavazza, 2025).

Cultural meaning is not merely an ornamental aspect of vocabulary; rather, it constitutes the fundamental logic that unites a linguistic community. High-frequency lexical items – such as kinship terms, evaluative adjectives, and words denoting basic social relations – embody centuries of social practice. These terms encode moral expectations, relational hierarchies, affective norms, and community-specific modes of categorizing experience. They serve as semantic anchors; the removal of their nuanced meanings precipitates a shift in the entire conceptual framework of a language (Wierzbicka, 1996; Goddard and Wierzbicka, 2013).

This issue extends beyond a mere linguistic concern. When artificial intelligence systems mediate meaning across languages, they implicitly shape users’ perceptions of those languages. For example, if a model reduces a culturally nuanced term such as Lingala lexeme mwana to English child or condenses the moral and relational complexity of malamu into a generic term like good, it fails to accurately convey the semantics of Lingala and instead imposes English conceptual categories onto the Lingala linguistic framework. This imposition often goes unnoticed precisely because the resulting text appears fluent and coherent. Nevertheless, the cumulative effect is detrimental: meanings become diluted, cultural structures are flattened, and low-resource languages suffer not only from diminished visibility but also from a loss of conceptual integrity.

In high-resource languages, the extensive scale of training corpora facilitates the preservation of nuanced meanings. Conversely, for low-resource languages – particularly those underrepresented in digital text – LLMs reconstruct meaning primarily through analogy rather than direct exposure. These models predominantly rely on English (Guo et al., 2024; Wendler et al., 2024), thereby importing conceptual distinctions that may not align with the cultural logic of the target language. This asymmetry is structural: low-resource languages are compelled to conform to categories that did not originate from them.

This highlights the growing importance of cultural meaning – not just as a sentimental recognition of linguistic diversity, but as a critical scientific and technological necessity. Artificial intelligence systems that overlook cultural semantics risk producing distorted interpretations, misleading educational content, and biased representations of communities. This risk is particularly significant for languages like Lingala, which have a rich oral tradition but limited digitized textual resources. Without explicit protective measures, AI systems may act as agents of semantic assimilation, thereby undermining the very categories that give the language its unique identity.

Supporting low-resource languages cannot be adequately addressed merely by increasing the number of tokens in training corpora. Instead, it requires the development of methodological tools capable of detecting semantic shifts – tools that identify when cultural nuances have been altered or lost, rather than solely when translations are incorrect. Trilingual aligned embeddings, as discussed in this editorial, represent an initial step toward such an approach. These embeddings enable the direct observation of meaning within a geometric space shaped by actual language usage rather than by generative generalization. They highlight distinctions that large language models frequently obscure and, in doing so, facilitate the creation of technologies that recognize cultural differences not as noise but as fundamental elements of semantic reality.

In summary, cultural meaning is significant because languages convey more than mere information; they embody perspectives, moral frameworks, social relationships, and ways of life (Malt & Majid, 2013). As artificial intelligence increasingly mediates linguistic experiences, preserving these dimensions becomes imperative. This preservation serves as a crucial criterion for determining whether multilingual technologies support human diversity or unintentionally diminish it.

3. A Trilingual Semantic Observatory

To understand how Large Language Models transform meaning across different languages, it is essential to adopt a perspective external to the models themselves. No matter how meticulously prompts are crafted, they confine us within the models’ interpretive frameworks: the model not only generates the response but also defines the semantic parameters from which the response arises. What is missing is a completely external vantage point – an independent reference framework that allows for the identification, measurement, and contextualization of semantic distortions. The trilingual semantic observatory we have developed through aligned embeddings of Russian, Lingala, and French serves precisely this function. It is not merely a computational tool; rather, it constitutes an epistemic instrument that enables the perception of meaning on its own terms, rather than through the lens of generative approximation.

To construct the trilingual semantic space used in this study, we integrated two sets of pre-trained distributional models (Russian and French) with a newly developed Lingala embedding model specifically trained for this research. The Russian and French embeddings were derived from widely used, publicly accessible corpora and were trained using the skip-gram architecture of word2vec (Mikolov et al., 2013) on extensive general-purpose text collections. These embeddings serve as high-quality baselines for high-resource Indo-European languages and provide a stable reference geometry for cross-lingual alignment.

The Lingala embeddings were developed from the ground up using a carefully curated corpus comprising newspapers, religious texts, radio transcripts, social media posts, and publicly available educational materials. Given that Lingala is a low-resource language, the training corpus was relatively limited in size; however, meticulous preprocessing – including orthographic normalization, diacritic unification, and the removal of noise and duplicate content – was employed to maintain consistency across sources. The model was trained using the skip-gram approach with 300-dimensional vectors, a window size of five, negative sampling (k = 5), and ten training epochs, adhering to established guidelines for small- to medium-sized corpora.

Following the training phase, the three sets of embeddings (Russian, Lingala, and French) were aligned within a shared semantic space using an orthogonal Procrustes transformation (Xing et al., 2015; Artetxe et al., 2018; see for review Ruder et al., 2019).

This methodological approach, which integrates high-resource pre-trained embeddings with a specialized Lingala model, ensures both linguistic accuracy and cultural sensitivity in the analysis. Furthermore, it guarantees that the resulting trilingual manifold remains independent of any specific LLM architecture, making it suitable for use as an external auditor in evaluating LLM semantic fidelity.

The strength of this trilingual semantic observatory lies in its ability to perform triangulation.

Russian offers a lexicon marked by high morphological granularity and conceptual differentiation; French contributes the stability and broad scope typical of a well-resourced Romance language; Lingala provides a relational, socially embedded semantic framework characteristic of many Bantu languages. When these linguistic systems are aligned through an orthogonal transformation, independent of the influence of English-based training, a geometric space emerges in which languages reveal their intrinsic conceptual logics as well as their intersections with one another.

This domain does not present translation pairs; instead, it reveals underlying structures. It uncovers the internal coherence of each lexical system and its distinctive method of organizing experience. Words cluster not according to dictionary definitions but based on shared pragmatic functions, relational roles, evaluative significance, and cultural salience. The resulting geometry forms a topographical map of conceptual worlds, illustrating where meanings converge, diverge, and where they resist confinement within the restrictive categories of English without incurring loss.

From the perspective of supporting low-resource languages, this issue is critical. Lingala, like many African languages, experiences a dual form of invisibility within contemporary AI: it is underrepresented in training datasets, and its conceptual frameworks do not align directly with the feature distributions characteristic of high-resource European languages. Consequently, Lingala is particularly susceptible to being subsumed into the semantic framework of English – a process that constitutes conceptual overwriting rather than genuine translation. The observatory offers a method to identify this overwriting empirically, using measurable geometric analysis rather than relying on conjecture.

French plays a pivotal role in this context, functioning not as a gatekeeper but as a high-resource intermediary that facilitates alignment while imposing significantly less conceptual pressure than English. In numerous multilingual ecological settings, French has historically served as a bridge between linguistically distant systems. Similarly, in this computational context, it enables the comparison of Russian and Lingala without subsuming the low-resource language into the semantic framework of the dominant global lingua franca.

The observatory enables the identification of tensions that LLMs tend to obscure. This is not due to deficiencies in the models themselves but rather because they lack the conceptual incentives and linguistic grounding necessary to maintain distinctions for which the English language offers no straightforward template.

In this context, the trilingual semantic observatory serves not only as a comparative tool but also as an ethical intervention designed to preserve the intellectual integrity of low-resource languages within an artificial intelligence ecosystem that frequently favors the familiar at the expense of cultural uniqueness.

Before examining the case studies themselves, it is important to clarify their intended purpose. This editorial does not aim to provide an exhaustive survey of Lingala semantics, nor to identify every pattern of drift in LLM behavior. Instead, its objective is to illustrate – through carefully selected examples – how a trilingual semantic space can serve as a diagnostic tool, revealing the nuanced ways in which meaning is preserved, altered, or subtly overwritten when processed by LLMs.

Core lexical items serve as ideal entry points for this investigation. Although they may seem straightforward on the surface, they embody profound cultural significance. These words occupy a critical intersection among cognition, social norms, and lived experience. They shape how communities categorize relationships, evaluate actions, and conceptualize personal identity. If any aspect of linguistic meaning is culturally grounded, it is this core lexicon. Moreover, if any component of meaning is vulnerable to English-centric compression in LLMs, it is this particular set of words.

The two examples chosen for this study are deliberate and central to understanding how Lingala encodes kinship and evaluation – two of the most significant conceptual domains in any language. Their behavior within the embedding space is both illustrative and insightful. Furthermore, the way LLMs process these examples, when analyzed within this geometric framework, clearly demonstrates the need for independent semantic auditors in multilingual AI.

4. Case Study 1: The Multi-Dimensionality of mwana

The word mwana provides a particularly insightful perspective on how cultural meanings are subtly reshaped when mediated through English-dominant LLMs. In Lingala, mwana is not a narrow lexical term limited to the category of “child.” Instead, it is a relational and socially embedded concept that spans multiple semantic fields simultaneously. It can refer to a biological child, a younger family member, a youth, a dependent, or a person defined by generational or social asymmetry. In discourse, mwana extends far beyond age classification; it encodes relational positioning, respect, responsibility, and kinship structure.

Yet, when we turn to modern LLMs, their English-based interpretive framework typically reduces all these layers to a single term. This simplification is not incorrect; rather, it is simply insufficient. What is lost is not lexical accuracy but semantic structure: the network of relationships through which mwana acquires its cultural meaning.

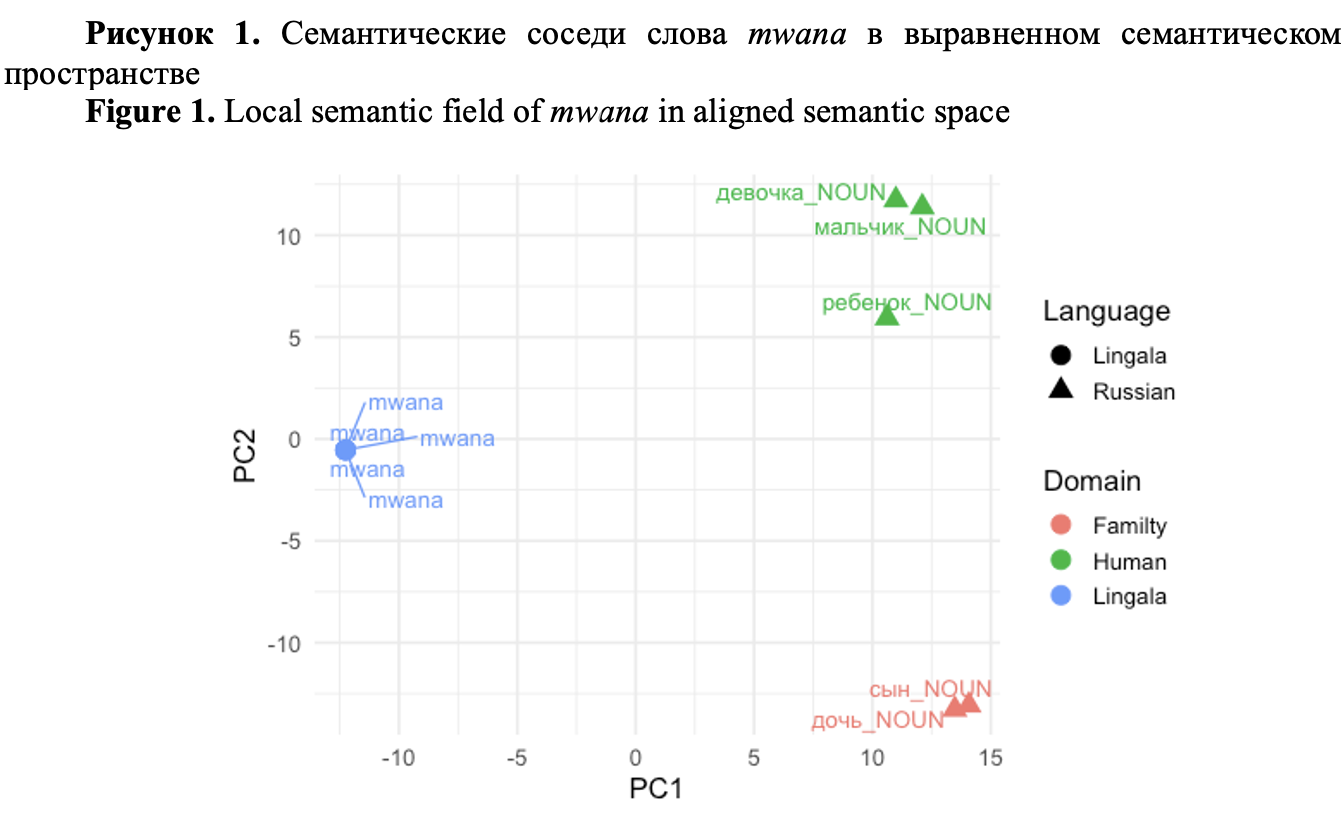

The trilingual embedding space (Fig. 1) reveals this richness in a way that no bilingual dictionary entry can. When we project the relevant region of the aligned manifold and examine the neighborhood of mwana, the Russian words surrounding it do not form a single, neat cluster labeled “child.” Instead, we observe multiple Russian lexemes ребёнок, девочка, мальчик, сын, дочь occupying distinct positions, each with its own local cluster of neighbors. These Russian words are not interchangeable; they encode gender and age in different ways. The manifold reflects this by treating them as separate, though related, centers of gravity. Mwana, by contrast, does something more interesting. It does not sit directly on top of any one Russian point; it does not “become” сын, ребёнок, or девочка. Instead, it occupies a position that touches several of these Russian clusters simultaneously. Geometrically, it is pulled toward all of them without collapsing into any single one.

Рисунок 1. Семантические соседи слова mwana в выравненном семантическом пространстве

Figure 1. Local semantic field of mwana in aligned semantic space

The repeated use of the term mwana within the Lingala cluster is intentional. Each instance corresponds to a distinct Russian lexical equivalent. By presenting multiple “translations” of mwana, we demonstrate that this single Lingala lexeme encompasses a conceptual domain that, in Russian, requires several semantically distinct terms. In other words, mwana is not under-specified; rather, it is culturally hyper-specified – its meaning derives from the relational logic inherent in Lingala kinship systems, as opposed to the classificatory logic characteristic of Indo-European languages.

Lingala uses extended descriptive phrases to distinguish between daughter and son; however, these are analytical constructions rather than independent lexical items. The primary lexeme, mwana, continues to serve as the dominant and culturally significant term. For semantic analysis, the crucial factor is not whether a language can paraphrase such distinctions but whether it lexicalizes them. Russian lexicalizes these distinctions, whereas Lingala does not, and this contrast is precisely what the embedding space reveals.

The resulting visualization reveals this asymmetry through a geometric representation. Russian terms are divided into distinct gendered and functional clusters, each exhibiting tight grouping. In contrast, the term mwana occupies a significant position distant from all clusters – not due to semantic ambiguity, but because it simultaneously spans multiple relational dimensions. This contrast between the lexical specificity of Russian and the relational generality of Lingala exemplifies the cultural structure that LLMs often tend to obscure.

Now, consider how a typical LLM processes the same term. When queried in English with the question "What does mwana mean in Lingala?", most models provide a brief and confident definition, such as "means child". At best, they may acknowledge that the term can refer to either a boy or a girl. However, it is uncommon for these models to address the broader relational and kinship connotations, the extension of meaning to youth or dependents, or the pragmatic functions related to forms of address and respect. In essence, the model selects one of the Russian or English conceptual equivalents – ребёнок/child (i.e., treats mwana as if it were merely a direct local counterpart).

From the perspective of LLM, this represents a benign approximation. However, when viewed within the context of the trilingual manifold, it constitutes a discernible loss of structural complexity. The model does not generate erroneous information; rather, it performs a form of semantic compression influenced by the English language and the organization of multilingual training data.

This type of distortion is precisely what remains undetectable when examining model outputs alone. Without native intuition regarding Lingala, one might never suspect any loss of meaning from the gloss alone. The trilingual semantic observatory changes this scenario by revealing that the term mwana is semantically distributed across multiple Russian clusters. It allows us to trace how its cultural significance occupies a region within the semantic manifold rather than a singular point.

From an audit perspective, the term mwana serves as a diagnostic tool, as its distributional patterns reveals discrepancies between corpus-based semantics and explanations generated by LLMs. This case illustrates how the model’s architecture, coupled with the predominance of English in training datasets, tends to prioritize rigid, monocentric categories, whereas the language itself employs more fluid, relational boundaries.

Importantly, this issue extends beyond Lingala. Many low-resource languages encode fundamental concepts such as kinship, social roles, and moral agency using terms that encompass broader or differently delineated conceptual domains compared to their English equivalents. In the absence of an external semantic reference, it is impossible to determine whether a LLM accurately preserves these conceptual nuances or oversimplifies them. The mwana case study illustrates that aligned embeddings can function as such a reference: an independent, culturally grounded benchmark for understanding meaning prior to its mediation through English.

In this context, the term mwana functions both as a lexical item and as a cautionary signal. It illustrates the ease with which LLMs can produce seemingly accurate outputs while subtly altering the underlying conceptual framework. Moreover, it demonstrates that existing methodologies – specifically, corpus-based, geometrically interpretable embeddings – enable the detection of such shifts. LLMs do not fail to interpret Lingala due to an inability to translate words; rather, their misinterpretation arises from the imposition of English conceptual structures onto the translation process. The trilingual embedding space reveals this phenomenon by indicating that Lingala’s categorical system is more expansive and relational, whereas Russian’s is more segmented and categorical. English’s default categories correspond more closely to the latter system. Consequently, LLMs, which are predominantly trained on English-centric corpora, implicitly assume that all languages conform to English-like conceptual patterns.

Thus, LLMs tend to reduce culturally rich relational concepts into narrowly defined, English-centric labels. Kinship terms highlight this issue clearly due to the evident mismatch between languages where a single word in Lingala corresponds to multiple terms in Russian. However, evaluative terms, despite their apparent universality, present an even greater challenge.

5. Case Study 2: The Evaluative Landscape of malamu and mabe

If mwana illustrates how kinship and age categories can vary significantly across linguistic systems, the pair malamu – mabe demonstrates an equally striking divergence in how communities evaluate people, actions, relationships, and experiences. Evaluative vocabulary is one of the most revealing aspects of any language: it is where cultural expectations, moral intuitions, social norms, and emotional judgments intersects. It is here – arguably more than anywhere else – that LLMs tend to overwrite culturally nuanced distinctions with a flattened, generic positivity/negativity binary inherited from English.

In Lingala, malamu is not simply translated as “good,” nor is mabe merely “bad.” While these English equivalents point in the right direction, they fail to capture the rich conceptual nuances embedded in the terms. Linguistically and culturally, malamu conveys warmth and encompasses notions of kindness, moral excellence, social appropriateness, and the relational sense of doing right by others. It can describe a person’s character, a helpful gesture, the atmosphere of an encounter, or the social acceptability of an action. Its opposite, mabe, similarly combines moral seriousness with social judgment: it refers not only to poor quality but also to harmful behavior, unacceptable conduct, and an ethically troubling disposition. These terms lie at the intersection of individual psychology, communal ethics, and the social context in which people act.

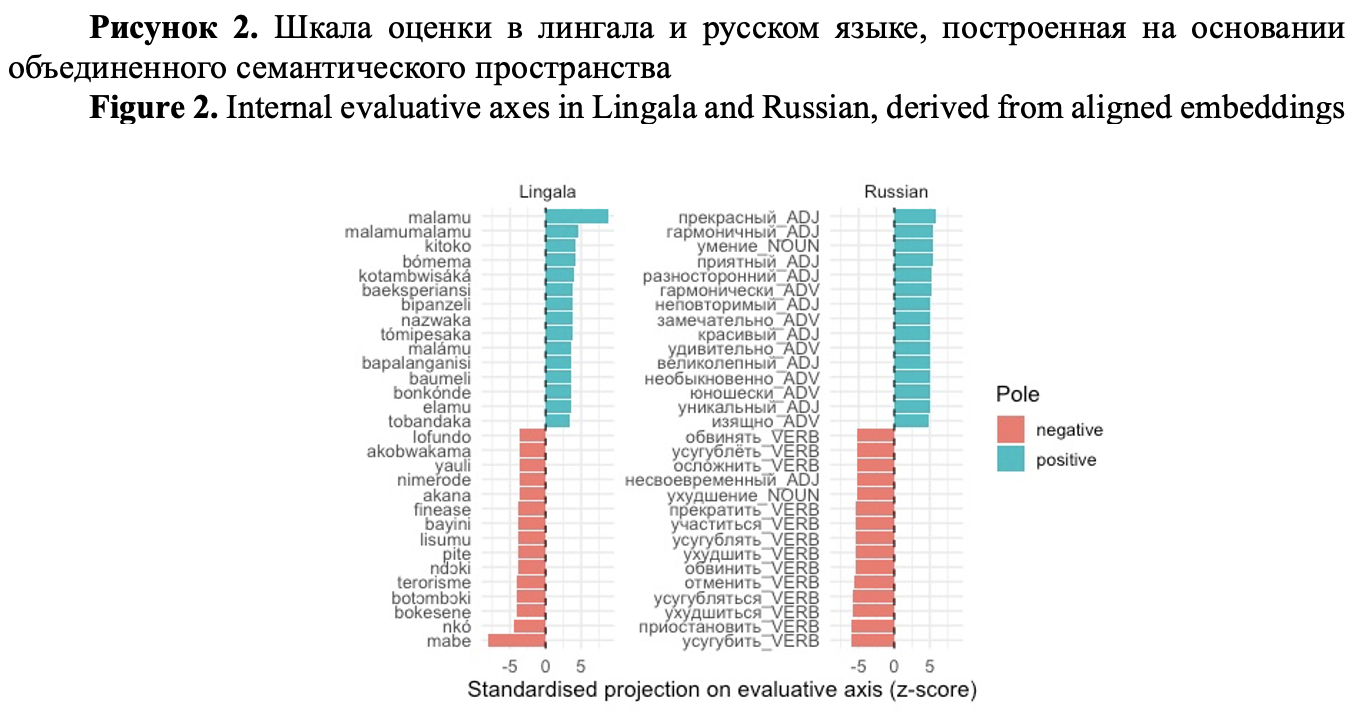

When we embed words into a shared vector space, this richness becomes geometrically visible (Fig. 2). We began by taking the embeddings for Lingala: malamu (positive pole) and mabe (negative pole), Russian: хороший (positive pole) and плохой (negative pole). From each embedding space (Lingala and Russian separately), we computed a semantic axis: for Lingala evaluative axis = vector (malamu) – vector (mabe), for Russian evaluative axis = vector(хороший) – vector (плохой). This yields two internal evaluative axes, each one reflecting the native structure of evaluative meaning in that language.

Then, for each language, we projected all words in the lexicon onto its own evaluative axis, standardized these projections (z-scores within each language), selected the top 15 most strongly positive and top 15 most strongly negative words along each axis and plotted them as horizontal bar charts, with one panel for Lingala and one for Russian. This approach reveals how each linguistic community organizes the conceptual domain of evaluation through natural co-occurrence patterns.

Panels (Fig. 2) show the top positive (turquoise) and negative (red) lexical items located along each language’s evaluative axis. Scores represent standardized projections (z-scores) onto each language’s own evaluative vector. The resulting distributions highlight major cross-linguistic differences in how evaluative meaning is organized: Lingala clusters around relational and moral appropriateness, while Russian emphasizes dispositional, aesthetic, and functional aspects.

Рисунок 2. Шкала оценки в лингала и русском языке, построенная на основании объединенного семантического пространства

Figure 2. Internal evaluative axes in Lingala and Russian, derived from aligned embeddings

Within the Lingala segment of the embedding space, the term malamu functions as a central, densely interconnected node that unites words related to social harmony, moral intergrity, emotional warmth, and relational propriety. Its closest lexical neighbors encompass concepts of positive interpersonal behavior, commendable character traits, and culturally endorsed conduct. These associations illustrate a conceptual coherence of values that, in other languages such as Russian are articulated through several distinct lexical categories.

In contrast, the Russian evaluative axis is clearly divided into several distinct semantic domains: aesthetic approval, functional adequacy, and positive affect. The negative pole similarly disperses into terms denoting moral fault, functional failure, harmfulness, or psychological negativity. Russian conveys evaluative distinctions through a lexically diverse system, in which different subdomains of value are expressed through distinct lexical items. What Lingala treats as a breakdown in social ethics, Russian often describes as a defect in quality or an act of wrongdoing.

Lingala exemplifies a relationally integrated model of value: the term malamu does not merely signify but encompasses social correctness, moral appropriateness, interpersonal harmony, and positive emotional connotations simultaneously. Conversely, its antonym, mabe, similarly unites moral reprehensibility, social impropriety, and harmful behavior into a single concept, whereas Russian typically differentiates these aspects across multiple lexical items.

This distinction becomes markedly evident in the geometry derived from embeddings.

The evaluative meaning in Lingala forms a cohesive conceptual continuum, whereas in Russian, it manifests as a constellation of distinct clusters. These structural differences, derived from usage-based embeddings, underscore significant cultural distinctions between the two languages. When prompted in English, even advanced language models consistently reduce the Lingala term malamu to simplistic equivalents such as “good,” “positive,” or “nice,” often accompanied by superficial explanations that fail to capture the term’s relational and moral complexity. The models’ internal training biases, particularly the predominance of Western textual genres and English ontological categories, tend to enforce a reductive evaluative dichotomy. Consequently, the conceptual unity of malamu is fragmented, with English glosses typically selecting the least culturally specific and socially grounded dimension of its meaning. A similar pattern occurs with the term mabe, which large language models frequently render as the generic opposite “bad,” thereby neglecting the socially evaluative significance it holds in Lingala.

The result represents not merely a simplification but a conceptual misalignment that obscures the relational, moral, and social evaluations inherent in Lingala. This misalignment is unequivocally demonstrated by the embedding manifold: Lingala’s evaluative field is dense and cohesive, Russian’s is dispersed, and English reduces both into a minimal binary framework.

The embedding geometry reveals this interpretive erasure with remarkable clarity. While the manifold displays an extensive, culturally cohesive evaluative region, LLM generates a singular point. Furthermore, where the distributional structure uncovers intertwined moral and relational meanings, the LLM replicates the English inclination to distinguish moral judgment from social propriety and aesthetic quality. In other words, the LLM does not simply mistranslate these terms; it fundamentally misrepresents the evaluative structure itself.

This case illustrates the vulnerability of core evaluative terms within multilingual AI systems. Such terms encompass conceptual domains that vary substantially across cultures and carry considerable significance in shaping how communities interpret behavior, emotion, and interpersonal relationships. When LLMs homogenize these distinctions, they do not merely commit a linguistic error; rather, they risk altering the conceptual framework through which language is understood. Importantly, this error is often imperceptible to users. A compelling explanation in English may create an illusion of accuracy, even when the underlying cultural meaning has been diminished.

The malamu – mabe case thus provides a secondary diagnostic perspective on the multilingual behavior of LLMs. It corroborates the observations made in the mwana case but approaches the issue from a distinct semantic dimension. Specifically, the challenge extends beyond kinship, age, and categorical boundaries to encompass the moral and evaluative frameworks inherent in a language. This example demonstrates how embeddings characterized by precision, distributional properties, and cultural fidelity can uncover distortions that would otherwise remain concealed beneath the ostensibly seamless surface of English paraphrase.

6. What the Two Cases Reveal Together

A comparative analysis of mwana and malamu/mabe elucidates a pattern that remains largely obscured when examining prompts in isolation. Although these terms initially appear to belong to distinct semantic domains, they share a common structural logic within the trilingual semantic space. Both function as semantic radiators, extending their meanings across multiple conceptual domains rather than residing within a singular, well-defined category. The distributional geometry of these terms reveals the underlying logic of Lingala as a meaning-making system, wherein relationality, moral stance, social positioning, and pragmatic appropriateness are intricately interwoven rather than compartmentalized into discrete lexical categories.

When examined from this perspective, the two case studies do not serve as isolated examples but rather as complementary insights into the underlying structure of the language. In the case of mwana, relational identity encompasses dimensions such as age, kinship, dependency, and communal belonging. Similarly, in malamu and mabe, evaluative judgment integrates moral, emotional, and social aspects into a unified conceptual domain. This analysis reveals a depiction of Lingala wherein the lexicon is not organized according to the narrow categorical divisions characteristic of Indo-European languages. Instead, many core terms occupy expansive conceptual domains where meaning is shaped through context and relational dynamics rather than fixed categorical boundaries.

The architecture characterized by relationality, overlap, and contextual vitality is precisely what is lost when LLMs generate responses to prompts. These models fail to apprehend the multi-centered gravitational significance of mwana or the evaluative – moral integration inherent in malamu. Instead, they reduce these semantic fields to their nearest English equivalents. This reduction does not simply omit a nuance; rather, it fundamentally reframes the conceptual core of the language. Consequently, it aligns Lingala with the categorical assumptions embedded in Russian or English, thereby distorting the semantic framework that native speakers intuitively employ in everyday communication.

When the two cases are considered in dialogue, a broader insight emerges. The issue is not the misinterpretation of isolated words but rather the systematic misalignment between the manner in which LLMs structure meaning and the way Lingala organizes semantic content. The embedding manifold demonstrates that Lingala does not partition the semantic space into narrowly defined categories, whereas LLMs, influenced predominantly by English-centric training data, do. At the intersection of these two systems, the tendency to simplify predominantly occurs in one direction.

The synthesis of the two examples thus demonstrates both the value and necessity of our approach. Embeddings that are aligned across languages yet remain independent of generative bias provide a unique method for detecting structural mismatches. These embeddings reveal not only the flattening of individual words but also the extent to which entire conceptual domains are susceptible to being drawn into the dominant influence of English. By comparing the kinship domain with the evaluative domain, it becomes evident that this drift is systematic rather than incidental; it follows a predictable pattern grounded in the generalization processes of LLMs and the manner in which low-resource linguistic categories are subsumed within high-resource conceptual frameworks.

What initially presents as two distinct case studies ultimately converges into a unified analytical argument: to comprehend the behavior of LLMs in multilingual contexts, it is essential to move beyond translation and examine the underlying geometry of meaning. The trilingual semantic space renders this geometry observable and, in doing so, reveals precisely where, how, and why semantic fidelity may be compromised.

7. Embedding Diagnostics as an Auditor for LLMs

A central argument of this editorial is that multilingual LLMs cannot be adequately evaluated solely through prompting. While prompts reveal how a model responds, they do not indicate whether the model’s internal semantic architecture aligns with the cultural logic of the language it is intended to represent. This distinction has gained increasing significance, as recent studies demonstrate that LLMs exhibit systematic cultural biases, frequently defaulting to English-speaking norms even when generating non-English text (Masoud et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). Moreover, even in tasks unrelated to translation, these models display measurable distortions in their representation of social roles, moral categories, and culturally grounded concepts (Pistilli et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025).

To reveal such distortions, it is necessary to employ tools that assess meaning independently of the model. Aligned embeddings serve as an external semantic reference point of this nature. Unlike generative models, embeddings do not inherit biases related to generation nor optimize for fluency. They neither interpolate nor smooth conceptual boundaries, nor do they assimilate culturally specific categories into universalized prototypes. Rather, embeddings represent words based on their empirical distributional behavior within corpora (Mikolov et al., 2013; Xing et al., 2015).

This independence is essential, as it enables the identification of instances where the geometry of a LLM’s semantic space deviates from corpus-based meaning, resulting in the collapse or elimination of linguistic distinctions.

Equally significant is the cultural sensitivity inherent in embeddings. Since distributional spaces arise from authentic language use rather than corpora heavily reliant on translation, they retain culturally specific semantic structures that are often obscured in LLMs. Furthermore, embeddings provide a geometric framework whereby semantic relationships are not inferred heuristically but are quantitatively measured. Distances, cluster boundaries, cross-lingual alignments, and divergences can all be precisely quantified. This capability facilitates systematic evaluation, including tracking semantic drift across different LLM versions, assessing alignment fidelity, identifying conceptual domains vulnerable to English-centric homogenization, and diagnosing instances when a model begins to overwrite the internal logic of a language.

From this perspective, embedding-based diagnostics constitute the foundation of a novel approach to multilingual AI auditing. They advance the field beyond reliance on anecdotes and ad hoc prompts, establishing a methodologically transparent and culturally grounded evaluation framework. Such diagnostics enable us not only to assess whether a LLM can generate text in a given language but also to determine whether it respects the conceptual distinctions that underpin that language’s worldview.

8. Toward a More Culturally-Aware Multilingual AI

If we accept that multilingual AI must be judged not only by surface fluency but by semantic fidelity, then a broader methodological shift becomes necessary. Recent work on cultural alignment in LLMs (Masoud et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Pistilli et al., 2024) has demonstrated both the urgency and the complexity of this task. What is missing, however, is a systematic way to connect these concerns with empirically grounded models of meaning.

The initial phase involves the development of semantic drift metrics – quantitative measures designed to compare semantic neighborhoods generated by LLMs with embedding manifolds derived from corpora. These metrics have the potential to elucidate how a model’s interpretation of the term mwana diverges from its distributional reality, as well as how evaluative terms such as malamu shift under the influence of English-dominant linguistic pressures.

However, metrics cannot be established without adequate data. Low-resource languages require community-developed corpora that accurately represent everyday language use, rather than relying on missionary texts, Bible translations, or parallel corpora compiled for convenience. In the absence of such corpora, the structure of the embedding space becomes limited, and LLMs lack a dependable foundation for capturing cultural meaning.

Subsequently, there is a need for multilingual semantic benchmarks that are rooted in culturally significant domains, such as kinship systems, evaluative lexicons, relational categories, and social roles. These benchmarks should evaluate not merely whether a LLM can translate a sentence, but whether it comprehends the conceptual framework that underpins the sentence.

Furthermore, it is imperative to reconsider approaches to cross-lingual alignment. For evaluation purposes, interpretable mapping methods should be adopted as standard practice. These methods maintain the intrinsic geometric structure of each language, rather than imposing English-centric configurations.

A promising approach involves hybrid architectures that integrate embedding geometry with LLM generation. Embeddings provide the conceptual framework that constrains or refines LLM interpretations.

It is essential to develop diagnostic visualizations such as semantic maps, drift charts, and cross-lingual PCA plots that render distortions perceptible. These tools serve not only as scientific instruments but also as educational and political resources. They enable language communities to observe how their conceptual frameworks are being transformed by AI and to engage actively in decisions regarding the future development of these systems.

Collectively, these steps delineate a research agenda with the potential to fundamentally transform multilingual NLP. Rather than regarding languages as interchangeable containers of text, AI systems can be developed to acknowledge them as distinct entities characterized by unique histories, conceptual frameworks, and cultural contexts. This endeavor represents not only a technical challenge but also an intellectual and ethical imperative.

If pursued collaboratively, this agenda has the potential to foster a multilingual AI landscape wherein linguistic diversity is regarded not as an obstacle to be surmounted but as a valuable resource from which to learn.

Conclusion

The findings discussed in this editorial prompt a reconsideration of the concept of multilingual artificial intelligence. Contemporary LLMs demonstrate remarkable proficiency in generating persuasive and coherent text in numerous languages; however, this linguistic fluency may obscure a more nuanced and significant issue: whether these models retain the cultural frameworks of meaning intrinsic to each linguistic system. This question becomes particularly complex when analyzing languages with conceptual structures that diverge markedly from English, such as Lingala.

Our trilingual aligned embedding space elucidates this phenomenon. By mapping Russian, Lingala, and French into a shared geometric manifold that preserves their intrinsic distributional properties, we can discern the conceptual frameworks that LLMs often obscure. The function of embeddings in this context is not to supplant LLMs but to serve as a counterbalance. They offer an independent and interpretable reference for meaning – one that is culturally sensitive, methodologically transparent, and not influenced by the statistical dominance of English. Consequently, embeddings facilitate a novel form of evaluation: a means to identify when LLMs respect the conceptual frameworks of a language and when they impose external schemas.

This editorial does not purport to identify all patterns of semantic drift across languages. Rather, it provides a conceptual framework and methodological foundation for such investigations. By aligning multiple languages within a shared distributional space, we are able to visualize, quantify, and critically examine meaning – its structural properties, cultural nuances, and areas of divergence from AI-generated interpretations. The case studies presented herein serve as initial explorations rather than definitive conclusions. They indicate that low-resource languages warrant special attention and that evaluation frameworks should extend beyond fluency to emphasize semantic fidelity.

As generative AI becomes increasingly integrated into education, translation, knowledge access, and cultural production, preserving linguistic specificity is imperative. It is a fundamental requirement for developing ethical and equitable multilingual technologies. If AI systems are to move beyond merely reproducing dominant conceptual worldviews, they must be coupled with external semantic tools – mechanisms capable of identifying what is lost, what is retained, and what requires critical re-evaluation in cross-lingual transfer.

Aligned embeddings provide a valuable tool for advancing multilingual artificial intelligence that not only supports multiple languages but also respects the distinct ways in which these languages structure meaning. Future progress in this area will require interdisciplinary collaboration, community-focused data collection, transparent methodologies, and the development of evaluation metrics that prioritize cultural semantics as a fundamental consideration rather than a secondary concern.

This moment presents an opportunity to establish the intellectual and ethical standards governing multilingual AI. Let us choose a path that honors the worlds encoded by languages.

Declarations. We used service wordvice.ai (https://wordvice.ai) for English proofreading, including spelling, grammar, and stylistic edits. This service did not generate substantive content or perform any analysis. No generative tool made interpretive or methodological decisions without human oversight, and no confidential or personally identifiable data were shared to third-party services.

Thanks

Tatiana A. Litvinova acknowledges the support of the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation (the research was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of the state assignment in the field of science, topic number QRPK-2025-0013). Olga V. Dekhnich received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Reference lists

Artetxe, M., Labaka, G. and Agirre, E. (2018). A robust self-learning method for fully unsupervised cross-lingual mappings of word embeddings, Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P18-1073(In English).

Bird, S. (2020). Decolonising speech and language technology, in Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 3504–3519, Barcelona, Spain (Online). International Committee on Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.313(In English).

Blasi, D. E., Anastasopoulos, A. and Neubig, G. (2022). Systematic inequalities in language technology performance across the world’s languages, Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Volume 1: Long Papers, 5486–5505, May 22-27, 2022. DOI: 10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.376 (In English).

Goddard, C. and Wierzbicka, A. (2014). Words and meanings: Lexical semantics across domains, languages, and cultures, Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668434.001.0001(In English).

Guo, Y., Conia, S., Zhou, Z., Li, M., Potdar, S. and Xiao, H. (2024). Do Large Language Models Have an English Accent? Evaluating and Improving the Naturalness of Multilingual LLMs, Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics.https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.15956(In English).

Joshi, P., Santy, S., Budhiraja, A., Bali, K. and Choudhury, M. (2020). The state and fate of linguistic diversity in the NLP world, Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics., 6282–6293. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.560(In English).

Li, C., Chen, M., Wang, J., Sitaram, S. and Xie, X. (2024). CultureLLM: incorporating cultural differences into large language models, in Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS '24), Vol. 37. Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, Article 2693, 84799–84838. https://doi.org/10.52202/079017-2693(In English).

Litvinova, T. A., Mikros, G. K. and Dekhnich, O. V. (2024). Writing in the era of large language models: a bibliometric analysis of research field. Research Result, Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, 10 (4), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.18413/2313-8912-2024-10-4-0-1(In English)

Liu, H., Cao, Y., Wu, X., Qiu, C., Gu, J. et al. (2025). Towards realistic evaluation of cultural value alignment in large language models: Diversity enhancement for survey response simulation, Information Processing and Management, 62, 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2025.104099 (In English).

Malt, B. C and Majid, A. (2013). How thought is mapped into words, Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. Nov; 4 (6), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1251(In English).

Masoud, R., Liu, Z., Ferianc, M., Treleaven, P. C. and Rodrigues, M. (2025). Cultural Alignment in Large Language Models: An Explanatory Analysis Based on Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions, in Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 8474–8503, Abu Dhabi, UAE, Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/2025.coling-main.567/(In English).

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G. and Dean, J. (2013). Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space, in 1st International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2013, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, May 2-4, 2013, Workshop Track Proceedings, 2013. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1301.3781(In English).

Mirko, F. and Lavazza, A. (2025), English in LLMs: The Role of AI in Avoiding Cultural Homogenization, in Philipp Hacker (ed.), Oxford Intersections: AI in Society (Oxford, online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 Mar. 2025). https://doi.org/10.1093/9780198945215.003.0140(In English).

Pistilli, G., Leidinger, A., Jernite, Y., Kasirzadeh, A., Luccioni, A. S. and Mitchell, M. (2024). CIVICS: Building a Dataset for Examining Culturally-Informed Values in Large Language Models. Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 7 (1), 1132-1144. https://doi.org/10.1609/aies.v7i1.31710(In English).

Qin, L., Chen, Q., Zhou, Y., Chen, Z., Li, Y., Liao, L., Li, M., Che, W., Yu, P. S. (2025). A survey of multilingual large language models, Patterns, 6 (1), 101118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2024.101118(In English).

Ruder, S., Vulić, I. and Søgaard, A. (2019). A survey of cross-lingual word embedding models, Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 65, 569–631. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.1.11640(In English).

Wendler, C., Veselovsky, V., Monea, G. and West, R. (2024). Do Llamas Work in English? On the Latent Language of Multilingual Transformers, in Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 15366–15394, Bangkok, Thailand. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.820(In English).

Wierzbicka, A. M. (1996). Semantics: Primes and Universals, Oxford University Press, UK. (In English).

Xing, C., Wang, D., Liu, C. and Lin, Y. (2015). Normalized word embedding and orthogonal transform for bilingual word translation, in Proceedings of the 2015 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 1006–1011, Denver, Colorado. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/N15-1104(In English).