How Environmental Activists Persuade: A Multimodal Speech Act Approach

Abstract

Given the rising prominence of youth climate activists in global discourse and the lack of research on how they persuade multimodally, this study examines the integration of speech acts and gestures in their rhetoric. By bridging speech act theory and gesture analysis, the research explores an underexplored aspect of persuasive communication in environmental activism. Analyzing 1230 speech acts from prominent activists Greta Thunberg, Jamie Margolin, and Xiye Bastida, the research applies Aristotle’s rhetorical triad (ethos, pathos, logos) and Searle’s taxonomy of illocutionary acts to elucidate the strategic alignment of multimodal components with persuasive intent. Among the speech acts, 172 multimodal units (gesture – verbal couplings) were identified and classified into detailed multimodal categories, highlighting dominant uses of pragmatic and discourse-structuring gestures alongside varied facial expressions and postures. These couplings were categorized by function as follows: structuring discourse (n=51) emerged as the most frequent, followed by pragmatic functions (n=44), formulating thoughts (n=27), object-representing gestures (n=29), and action-representing gestures (n=21). Results indicate a predominance of emotional (pathos) and ethical (ethos) appeals reinforced through pragmatic gestures and expressive mimicry, with representational gestures less frequent but strategically significant. This multimodal integration confirms that persuasive efficacy in activist discourse is significantly enhanced by embodied, contextually sensitive communication practices. The findings underline the necessity of expanded analytical models in multimodal pragmatics, supporting future research directions integrating quantitative gesture analysis and advanced coding methodologies.

Keywords: Multimodal pragmatics, Multimodal communication, Environmental activists, Youth climate activism, Ecological discourse, Gesture analysis, Persuasive strategy, Speech acts

1. Introduction

1.1. Multimodality in pragmatics

Challenges in pragmatics, initially defined by its founder Charles Morris, involve questions of behavioural semiotics, which consists of two key elements: multimodality and sign behaviour. We can now assert that Morris’s conception of pragmatics is fundamentally a multimodal semiotic pragmatics, expanding the traditional pragmatic framework by integrating multiple semiotic modes into the analysis of communication. Multimodal pragmatics is an emerging research area that combines several semiotic modalities – such as spoken language, gestures, facial expressions, and visual elements – to analyze pragmatic competence and communicative interactions (Dicerto et al., 2018: 37–59; Beltrán-Planques and Querol-Julián, 2018; Freigang et al., 2017: 142–155). Pragmatic multimodal competence highlights learners’ abilities to use linguistic (speech) strategies effectively to express themselves adequately, comprehend each other accurately, and communicate successfully within specific contexts (Jiang, 2013). Kress (2009) argues for a social semiotic framework that examines how different semiotic modes – such as speech, gestures, images, and text – combine and interact in contemporary communication, offering insights relevant for analyzing multimodal aspects of public discourses. A multimodal perspective thus broadly positions multimodal pragmatics as an umbrella term that encompasses both verbal and non-verbal elements, crucial for effective communication and essential to consider when studying interlanguage pragmatics.

Therefore, this study’s relevance stems from the importance of non-verbal communication channels in processing and assimilating information. The objective of this study is to investigate how multimodal elements (especially gestures aligned with speech acts) function in the persuasive discourse of youth climate activists. This investigation is guided by two research questions:

1. What types of illocutionary acts dominate their speeches (the verbal component)?

2. How are these speech acts reinforced or modulated by gestures and other nonverbal cues?

According to Kibrik and Èl’bert (2008), only 39% of information is transmitted through verbal communication, whereas prosody conveys 28%, and non-verbal communication accounts for 33%. Furthermore, speech and gesture are inherently inseparable; gestures frequently complement verbal utterances, facilitate communicative goals, and enhance expressiveness (Kendon, 2004). While language remains the primary medium for conveying messages, communicators simultaneously – and often unconsciously – aim to prompt actions, motivate responses, or evoke emotions.

All natural languages employed in social interactions utilize multiple communicative channels. While these channels sometimes provide redundancy (e.g., saying "He turned left" while pointing left), they more often contribute new and distinct information. Enfield (2009) specifically explores how speech and gesture form integrated meaningful units, asserting that utterances are inherently multimodal.

From this perspective, public speaking is viewed as an interaction among various modalities (communication channels and sign systems). Contemporary researchers highlight that, in prototypical oral communication, alongside distinguishing individual words, we capture intonation, pay attention to voice qualities and non-verbal sounds, and interpret the interlocutor’s facial expressions, postures, and movements. Additionally, multimodal communication research emphasizes focusing on both speaker and listener, noting that the distribution of roles among participants significantly influences communicative behaviour.

1.2. Research on multimodality

Multimodal research is commonly divided into two trends: visual and gestural (Iriskhanova, 2022). The visual trend investigates written texts featuring visual elements, such as newspaper articles, comics, posters, graffiti, photographs, advertisements, films, and video clips. Conversely, the kinetic or gestural trend examines public speaking, focusing on body movements and gestures.

Voice quality, amplitude, pitch, and timbre can provide essential supplementary information to utterances. Similarly, the gestural-visual channel can be considered multilayered. For example, a person may look with narrowed or wide-open eyes, briefly or extensively, with or without blinking, each layer potentially conveying independent meanings. As Abercrombie (1968: 55) famously stated, "We speak with our vocal organs, but we speak with our whole body." Ray Birdwhistell (2021: 3), who introduced the term "kinesics" to describe bodily postures, estimated that verbal communication accounts for no more than one third of human interaction content. While this exact figure remains debatable, it is undeniable that using multiple communication channels enhances – and sometimes multiplies – the meaning conveyed through the verbal channel.

The systematic investigation of multimodal communication is comparatively recent and has advanced largely because of digital technologies. Although Greek and Roman orators classified gestures, sustained empirical research did not begin until the latter half of the twentieth century, led by anthropologists, phoneticians, and social psychologists. Sign languages provide a compelling illustration of multimodality: they require the coordinated engagement of multiple articulators according to linguistic rules while fulfilling expressive demands; for instance, facial movements complement the two-handed manual channel (Loos et al., 2022). While hand gestures have been documented in detail, other expressive channels remain understudied. The face, in particular, is a site of numerous overlapping layers – movement of the forehead, eyebrows, mouth, teeth, jaw, head tilt, and gaze – yet it has attracted limited systematic attention. Facial expression is also culturally inflected (Russell, 1995). Japanese interlocutors typically attend to the eyes, whereas Americans tend to focus on the mouth; in Papuan culture, nose wrinkling, contrary to Ekman’s prediction, signals astonishment rather than disgust (Hömke et al., 2018). Laboratories worldwide have begun assembling richly annotated multimodal corpora, yielding important new insights (e.g., Kendrick, 2015). Core concepts of multimodal pragmatics are now being integrated with corpus-based methods that systematically analyze extensive collections of authentic language data, thereby broadening the empirical base of pragmatic research and extending classical pragmatic theory.

Each human utterance is a highly orchestrated event, drawing upon a complex repertoire of communicative resources. Researchers estimate that speakers may utilize over 150 distinct signaling mechanisms – verbal, prosodic, gestural, postural, facial, and ocular. Although not all channels are activated simultaneously, the speaker continuously selects, synchronizes, and modulates these resources in real time. Rather than a solitary act of linguistic encoding (Sidiropoulou, 2020), communication becomes a multimodal performance – more akin to a symphonic composition than to a monophonic verbal string. As such, every spoken act is inherently multimodal, layered with concurrent signals that enrich, frame, or even subvert literal linguistic content.

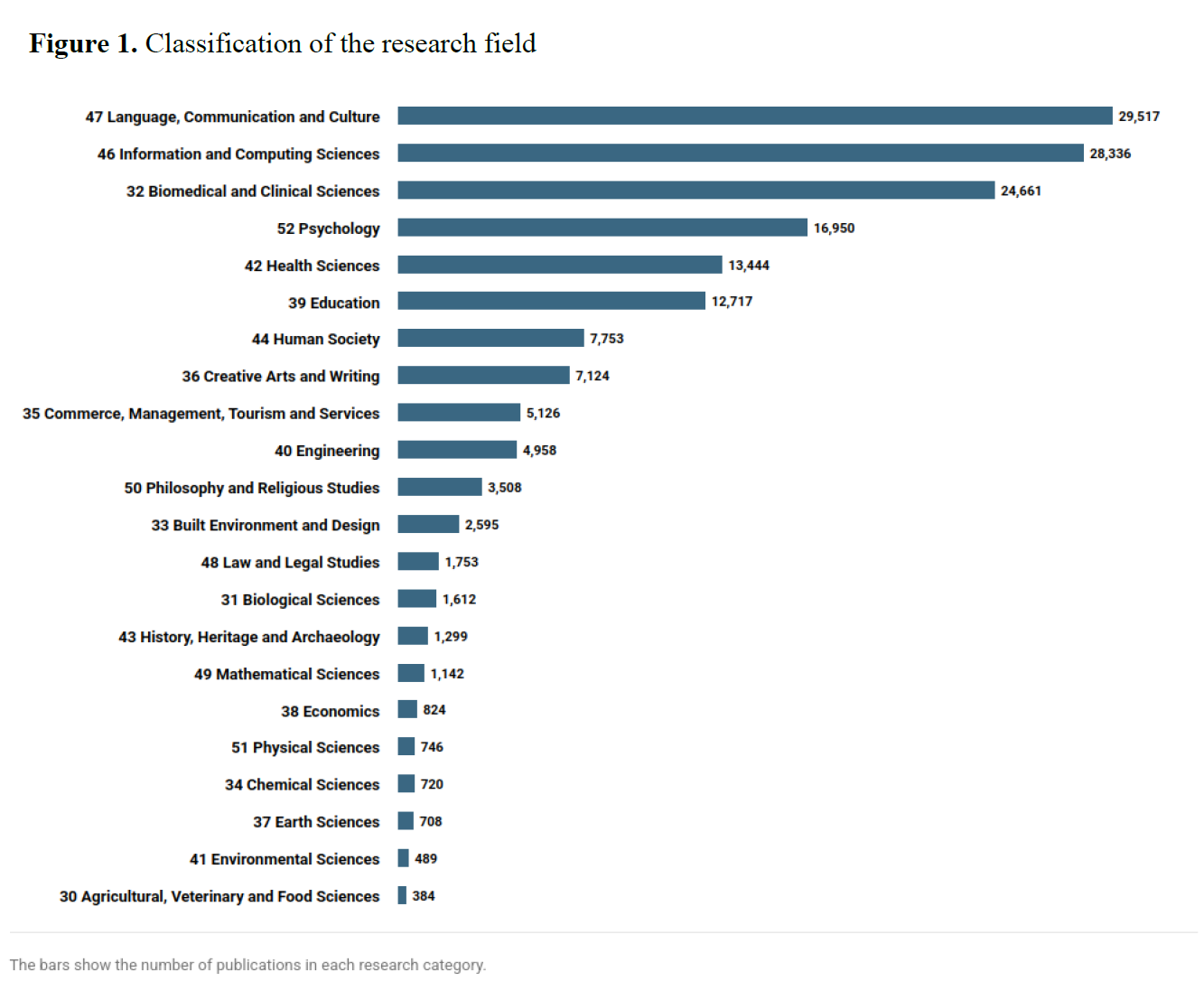

Multimodal pragmatics, as a field, has rapidly expanded beyond foundational linguistics into a range of applied domains (Norris, 2012). The analytical analysis of research field classification on the topic with the keyword "multimodal pragmatics"– retrieved using Dimensions AI on November 12, 2025, from the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection Database across all editions, including datasets, grants, patents, clinical trials, and policy documents as shown in Figure 1 – indicates the key research field as Language, Communication and Culture. The procedure below generated a search result of 83,288 articles.

In artificial intelligence and natural language processing, multimodal pragmatics provides key insights into how machines can interpret not only literal verbal content but also contextual cues, emotional tone, and interpersonal stance (Cambria, 2025). In translation studies, it allows for accurate rendering of multimodal texts, including films, advertisements, and social media posts, where meaning often hinges on co-textual visuals or gesture-based framing. In advertising, multimodal argumentation analysis helps deconstruct how emotional and logical appeals are conveyed not just through slogans, but also through imagery, colour, spatial design, and gaze orientation.

In applied linguistics, particularly in second language education, multimodality has become indispensable. Teachers increasingly rely on non-verbal semiotic resources – gestures, facial expressions, digital tools – to scaffold comprehension, manage classroom interaction, and support embodied cognition (Lim, 2020). This educational use of multimodal discourse draws on various theoretical frameworks: social semiotics (Kress, 2009), multimodal pedagogical stylistics (Lei, Zhang, 2022), and systemic functional linguistics. Research shows how these frameworks enable the analysis of pair work, interactive lectures, listening comprehension, and video-based learning (Morell, 2018; Norte Fernández-Pacheco, 2016; Campoy-Cubillo, Querol-Julián, 2021). Jewitt (2006, 2023) explores the implications of integrating digital and multimodal approaches into education, emphasizing the necessity of recognizing multiple semiotic resources to effectively analyze and support contemporary literacy and communication practices. These studies consistently emphasize that meaning is co-constructed through ensembles of semiotic modes and that students’ engagement deepens when verbal input is embedded in a multimodal context.

Furthermore, multimodal corpus approaches to speech act theory enable fine-grained analysis of how communicative intentions are instantiated through gesture-speech synchrony, prosodic framing, and gaze orientation (Huang, 2021; Fang, 2023). These empirical frameworks not only enrich traditional pragmatics but also inform broader discourse studies in political rhetoric, clinical communication, and activist media.

From a cognitive perspective, the discovery of multiple cross-modal areas in the cerebral cortex suggests that human experience is profoundly multimodal. We perceive the world holistically, not through isolated channels. This principle directly informs multimodal learning, which engages multiple sensory and cognitive channels to allow for differentiated instruction (Goodwin, 2017). In this context, visual literacy is not passive recognition but "the ability to analyze the power of an image and its meaning in a particular context" (Duchak, 2014). Effective implementation relies on principles of adaptivity, accessibility, interactivity, and diversity – the latter requiring the integration of resources across verbal, visual, gestural, spatial, and digital semiotic channels (Bouchey et al., 2021).

According to Haryanti et al. (2023), the procedural objective of multimodal pragmatics in linguistics is the development of communicative, analytical, and integrative competences. These scholars argue that multimodal systems train cognitive flexibility and stimulus response discrimination across heterogeneous information sources. Furthermore, they emphasize that creative and critical thinking are essential, arising from the necessity to interpret, reorganize, and re‑express complex input across different media types, since multimodal meaning‑making involves also the integration of embodied and contextual signals in communicative interaction (Bucher, 2025). Recent work on multimodal complexity highlights that communicative competence encompasses the coordination of multiple semiotic modes and layered representational forms, which can be studied across features and registers in situated discourse.

In pragmatic analysis, multimodal learning intersects with the study of speech behavior that provides diagnostic access to the speaker’s intentionality, role identification, social alignment, and identity framing. Speech acts, gestures, and embodied expressions within instructional settings form structured behavioral data relevant to functional, interactional, and affective analysis (Machin, Mayr, 2012).

Pragmatics examines the intentional and contextually motivated selection of lexical units, grounded in both explicit communicative goals and implicit, habitualized speech experience. Over time, repeated patterns of linguistic behavior become internalized, operating below the level of conscious awareness as communicative intuition. Since linguistic behavior is shaped by social stratification – across dimensions such as nationality, age, education, and profession – pragmatic analysis naturally extends to the differentiated speech patterns of social groups.

1.3. Pragmatics in environmental discourse

According to Cox (2013), environmental activists are a prime example of individuals whose rhetorical competence is evident in their public discourse. From a rhetorical-argumentation perspective (Tindale, 2004), their aim is audience-oriented and context-sensitive: reasons are crafted for adherence within specific situations (i.e. environmental discourse) rather than judged only by abstract validity. Like politicians, media figures, and public speakers, they employ multimodal strategies to enhance persuasive impact. Their communicative success derives from a strategic integration of verbal content, prosody, facial expressions, and gesture. The urgency of the ecological crisis necessitates such persuasive multimodal performance, aimed at mobilizing public concern and political response.

Doyle (2012) argues that effective communication of climate change requires overcoming deeply ingrained cultural perceptions that position climate change as distant or future-oriented. She critically examines how visual representations – such as imagery of melting glaciers or endangered animals – often reinforce perceptions of climate change as an external environmental issue rather than an immediate, human-centered concern. Adopting a human‑centered lens, climate narratives gain traction when they link environmental change to lived conditions and responsibilities within local communities, aligning messages with audience values and concerns about everyday life (O’Callaghan et al., 2025). In the same vein, Miller (2025) argues that applying persuasion theory to climate communication—especially through narrative framing and moral appeals tailored to specific audiences—can enhance engagement and motivate climate‑friendly behavior by connecting abstract scientific information with individuals’ lived experience. Emphasizing culturally relevant messaging and story‑driven communication helps audiences interpret and internalize climate narratives in ways that resonate with their values and social identities.

Environmental activism is characterized by intentional communicative action grounded in personal experience and ethical commitment. Activists engage in discourse not only to disseminate information but to provoke affective and behavioral change. Recent research on visual and narrative strategies in climate communication shows that framing environmental messages through relatable, lived experiences and positive, solution‑oriented narratives can deepen engagement and motivate audiences to internalize and act on environmental issues (San Cornelio, Martorell and Ardèvol, 2024). Environmental discourse, hence, refers to the set of communicative practices – linguistic and non-verbal – used to articulate, frame, and circulate ecological concerns in ways that resonate with human values and social identities.

Among young environmental activists, shared social identity and moral conviction provide the motivational core for participation and framing, linking individual beliefs about collective agency with engagement in public action (Brügger, Gubler, Steentjes and Capstick, 2020). Their public speeches reflect deliberate value choice and self-determination, linking personal moral stance to collective agency and anchoring persuasive appeals in lived commitments.

However, despite the significant academic advancement made in multimodal pragmatics by far, the existing pile of literature has received scanty attention of youth climate communication. An investigation is thus necessary to understand how youth environmental activists combine speech acts with gestures to persuade. Existing studies have not systematically integrated speech act theory with gesture analysis in this context. This study addresses that gap by examining whether and how embodied cues (f.ex. gestures) correlate with the illocutionary component of activists’ speech acts. The integrated approach enables a shift from treating gestures as mere accompaniments to speech toward the analysis of complex multimodal performatives. The study empirically identifies and delineates the specifics of an emerging genre – the rhetoric of youth climate activism. We demonstrate that its persuasive power stems not from institutional authority, but from a unique combination of verbal strategies (e.g., direct directives, personal narratives) and non-verbal tactics (e.g., gestures conveying vulnerability, openness, and moral steadfastness). Previous analyses of climate activism rhetoric have focused on linguistic and emotional appeals (e.g., Cox, 2013; Tindale, 2004) but have rarely examined the gestural or multimodal aspect of these appeals.

Likewise, while multimodal pragmatics research has advanced in fields like education and human-computer interaction, its application to social movement discourse remains limited. This study bridges that gap by applying multimodal analysis to activist oratory. We aim to contribute new insights into multimodal persuasion by youth activists – a communicative mode distinct from that of politicians or older advocates. This study is the first to systematically integrate the analytical frameworks of gesture studies (Kendon, McNeill) with classical speech act theory (Searle) within the context of multimodal communication.

The research makes a methodological contribution to multimodal studies by developing and implementing a detailed annotation scheme, provided as a reference in the supplementary materials. This ensures the transparency and reproducibility of the analysis, aligning with the best practices in empirical research.

2. Materials and methodology

2.1. Participants and data sources

The study analyzes the speech behavior of three internationally prominent youth climate activists whose public discourse has gained widespread visibility on platforms such as TED and YouTube. The corpus for this study comprises public speeches by three representatives of the global youth climate movement: Greta Thunberg (Sweden), Jamie Margolin (USA), and Xiye Bastida (Mexico/USA). The purposive selection of these cases is driven by the need to represent the key discursive strategies within this movement. This approach allows us to analyze their speeches not as individual utterances, but as exemplars of the collective rhetoric of this community with its own distinct norms. We proceed from the premise that their communication enacts a specific genre of mass-media environmental discourse – the public speeches of young environmental advocates. This genre is distinct both from the rhetoric of adult politicians, which relies on institutional authority, and from the speech of NGO experts, which appeals to technical solutions. Young environmental ecologists have a unique persuasive challenge: lacking formal authority, they rely on moral appeal and personal ethos. The internal variation within the sample – Thunberg as a confrontational global leader, Margolin as a media- and legally-oriented strategist, and Bastida as an advocate for environmental justice – enables us to identify the invariant, core multimodal patterns of this genre, as well as its context-driven modifications.

The selection criteria also included global recognition, sustained activism, and multimodal public engagement. Each participant represents a distinct sociocultural background, enabling comparative insight across demographic variables.

Greta Thunberg (b. 2003), a Swedish environmental activist, is the initiator of the School Strike for Climate movement and a central figure in the Fridays for Future network. Her addresses to the United Nations and national parliaments have received substantial international coverage. Jamie Margolin, a Colombian-American activist (b. 2001), is the co-founder of Zero Hour, a youth-led climate justice organization. She is known for her direct engagement with legislative bodies and her emphasis on intersectional climate advocacy. Xiye Bastida (b. 2002), of Indigenous Mexican Otomi-Toltec descent, is affiliated with the Peoples Climate Movement and the Fridays for Future initiative. Her activism integrates environmental concerns with Indigenous epistemologies and intergenerational equity.

2.2. Data description

Data were drawn from nine environmental youth activist speeches:

- Greta Thunberg’s address to the UK Parliament (2019), her UN Climate Action Summit speech (2019), and her speech at the World Economic Forum (Jan 2020).

- Jamie Margolin’s testimony to the US Congress (2019, her TEDx Youth presentation in Columbia (2019), and her closing remarks at Sun Valley Youth Forum in Idaho (2019).

- Xiye Bastida’s speech at the “Climate Action: Race to Zero and Resilience” forum in New York (2022), her talk at the Bloomberg Green Festival (2024), and a main-stage Humanity Reimagined TED Conference presentation in Vancouver (2025).

Each speech ranged from 4 to 12 minutes, totaling ~80 minutes of material.

All speeches were transcribed verbatim from publicly available video recordings; the resulting scripts served as the basis for segmenting the discourse into individual speech acts and for identifying co-occurring multimodal cues.

2.3. Analytical framework and data processing

We segmented transcripts into individual speech acts based on predicate-finality boundaries, i.e. points where a main predicate and its complements conclude a proposition (often coinciding with a full sentence or independent clause end). For example, in the sentence "We need to act now because time is running out," we split at the conjunction to get two units: "We need to act now" and "because time is running out," each expressing a distinct proposition/intention. This segmentation criterion ensured that each unit reflected a self-contained instance of speaker intention. Following segmentation, each speech act was subjected to dual-layer annotation: first, at the locutionary level, capturing the formal linguistic structure and rhetorical tactic; and second, at the illocutionary level, identifying the communicative function as defined by the speaker’s intention. While not a standard segmentation in pragmatics, we found that predicate-final segmentation aligned well with the general cadence of speeches, their prosody, breath pauses and shifts in illocutionary expressions.

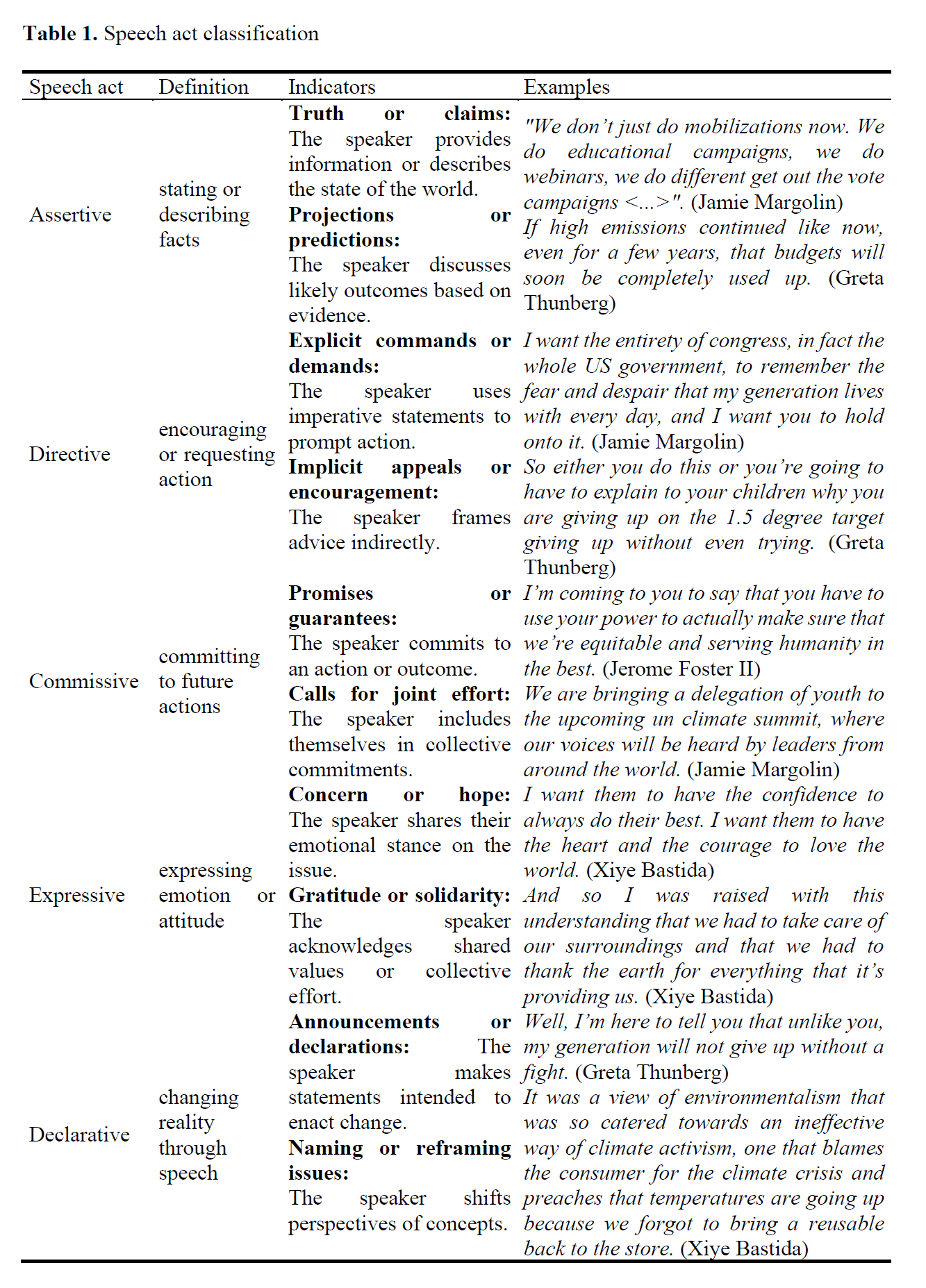

Illocutionary functions were categorized according to an adapted version of Searle’s (1969) taxonomy, which includes assertives (statements of fact or belief), directives (attempts to influence listener behaviour), commissives (commitments to future action), expressives (revelations of psychological states or attitudes), and declaratives (acts that effect change through utterance) (Barrero Salinas, 2023). This classification provides a stable framework for aligning verbal strategies with pragmatic functions across all speakers (Levinson, 2016).

We adopted Searle’s five illocutionary categories, but given the persuasive context, we treated some categories with nuance. Assertives were defined as statements that present states of affairs as true or factual (e.g. "The climate crisis is happening right now"), directives as utterances that attempt to get the audience to do something (e.g. "We have to come together and know that we can support each other to move forward"), commissives as commitments by the speaker to a future course of action (e.g. "<…> my generation will not give up without a fight"), expressives as verbalizations of psychological states or the speaker’s affective stance (e.g. "Our house is still on fire"), and declaratives as utterances that aim to bring about an institutional change in status by being said (e.g. "I am here before the whole country today announcing that we are instead <...> Generation Green New Deal."), which we expected to be rare given the speakers’ lack of formal institutional authority.

Given the persuasive context, each utterance was coded for the illocutionary type that best captured its dominant rhetorical function. When a speech act could plausibly fit two or more categories (for instance, an assertive that also indirectly invites action), the coders selected a single primary illocutionary act on the basis of the local persuasive strategy, resolving borderline cases through discussion until agreement was reached. This ensured that speech-act labels reflected the main communicative intention of the activists rather than a maximalist accumulation of possible readings.

To ensure the reliability of the speech act annotation, we calculated inter-annotator agreement using Cohen's kappa coefficient. Two trained coders independently annotated a randomly selected sample of 148 speech acts (12% of the total). The resulting Cohen's kappa coefficient was κ = 0.78, which indicates a substantial level of agreement based on standard benchmarks (Landis and Koch, 1977). Subsequently, all disagreements in the training sample were discussed and resolved, and the coders proceeded to annotate the entire corpus independently using the refined guidelines. A critical concern in multimodal research is the subjective nature of annotation. To address this, we established the reliability of our gesture coding scheme through formal statistical testing. Two annotators, after a joint training period, independently coded a stratified random sample representing 15% of the entire dataset. We employed Krippendorff's alpha, a conservative coefficient that accounts for chance agreement and is well-suited for categorical data, for its flexibility with different numbers of coders, sample sizes, and measurement levels (in our case, nominal categories for gesture types). The analysis yielded a coefficient of α = 0.78. Following standard guidelines where values between 0.80 and 0.67 are considered indicators of "substantial" or "good" agreement, our result of 0.78 falls within this acceptable range, confirming that the gesture taxonomy was applied consistently and that the reported frequencies are reliable.

To capture the multimodal dimension of activist discourse, the primary unit of analysis was defined as a multimodal composite: "linguistic expression + gesture." The boundary of each unit was determined by the end of a speech act, enabling one-to-one mapping between verbal and gestural sequences. This alignment permitted analysis of how gestures function in conjunction with verbal content to modulate, reinforce, or redirect communicative intent.

Persuasive tactics were examined through the classical rhetorical triad – ethos (credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical argumentation) – as conceptualized in Aristotle’s "Rhetoric". This triadic model (IxDF, 2016) was used to map the strategic deployment of multimodal elements within the discourse, allowing for integrated analysis of how speech acts and bodily expressions co-articulate persuasive meaning.

This study aims to experimentally combine rhetorical theory and pragmatics: Aristotle’s ethos/pathos/logos model provides a lens on persuasive tactics, while Searle’s speech act theory classifies communicative intentions, and gesture typologies (after Kendon, McNeill, etc.) reveal how physical cues complement those intentions. Departing from traditional syntactic or intonational criteria, this study segmented speech acts using a functional criterion of "predicative completeness", an approach justified by our multimodal framework. A segmentation unit was defined as a speech segment where the propositional core (the predicate and its core arguments) reached semantic and performative finality. This finality was frequently signaled multimodally as well as verbally, often aligning with the stroke phase of a co-occurring gesture (Kendon, 2004; McNeill, 1992). This technique enables the extraction of holistic multimodal utterances, where speech and gesture constitute an integrated pragmatic unit – a feature especially pertinent for analyzing the dynamic and affect-laden discourse of ecological activists.

2.4. Methodological approach

The study employs a combination of comparative analysis, content analysis, computational processing of statistical data, and multimodal analysis of semantic and functional correlations between verbal utterances and gestural behavior. Each method is integrated into a unified framework to investigate how linguistic and non-linguistic modes operate synchronously in the discourse of environmental activists.

Gestures are operationally defined as intentional hand movements that function as communicative signs within the interactional context. To categorize these gestures, the study adopts and refines a typological model grounded in the frameworks of A. Kendon, D. McNeill (Kendon, 2004; McNeill, 1992), and further developed by C. Müller and A. Cienki (Müller, 1998. 2023; Cienki, 2013). This model includes five primary functional categories: pragmatic gestures (including beats or pointing) serve to regulate discourse or emphasize points; thought-formulating gestures (often metaphoric motions) help the speaker conceptualize or package ideas; discourse-structuring gestures mark transitions or organize segments of the talk (e.g., counting on fingers, sectioning space); Representational gestures depict content, subdivided into object-representing (iconic gestures showing objects or shapes) and action-representing (pantomimic gestures illustrating actions).

Our gesture classification merges Kendon’s functional distinctions with McNeill’s categories of representational gestures, refined by Müller’s and Cienki’s work on pragmatic gesture functions; this unified scheme was tailored to fit the rhetorical context of speeches. We focused on hand/arm movements that were clearly timed with speech and appeared to convey emphasis or meaning. Small idle movements or unintentional fidgets were not counted as gestures.

In addition to hand gestures, we noted other nonverbal cues (facial expressions, body posture, eye gaze) qualitatively during the analysis to enrich interpretation, although the systematic coding focused on hand gestures. Notably, when an emotionally charged statement coincided with a facial display (e.g., frown, smile) or a posture shift, we recorded that context in our notes, but these were not quantitatively tallied like the hand gestures. This will be the focus of our next research to provide a more comprehensive multimodal analysis.

Firstly, we conducted this annotation manually, then with the use of specialized software ELAN, given the manageable size of the data. Coding and segmentation were conducted collaboratively by two researchers. First, they jointly discussed and refined the speech act categories and gesture types using a small subset of the data in order to develop a consistent operational approach. Segmentation into speech-act units was then carried out and reviewed jointly, with both researchers working together at the boundary-identification stage. In the subsequent annotation phase, the researchers alternated between roles – at times both coding the material together, and at other times one annotating while the other systematically reviewed and cross-checked the annotations – so that every segment and gesture label was verified by both analysts. Disagreements or ambiguous cases were resolved through discussion.

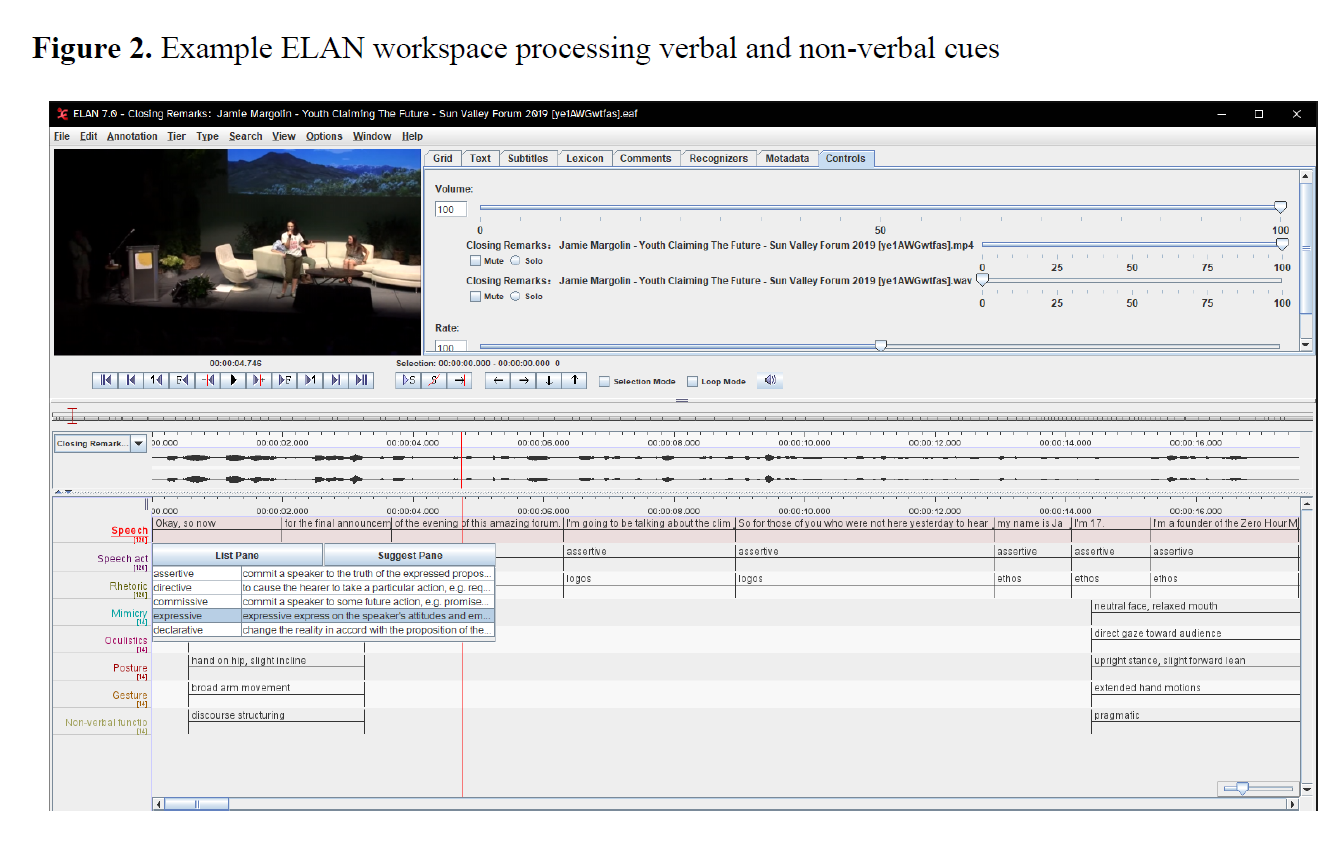

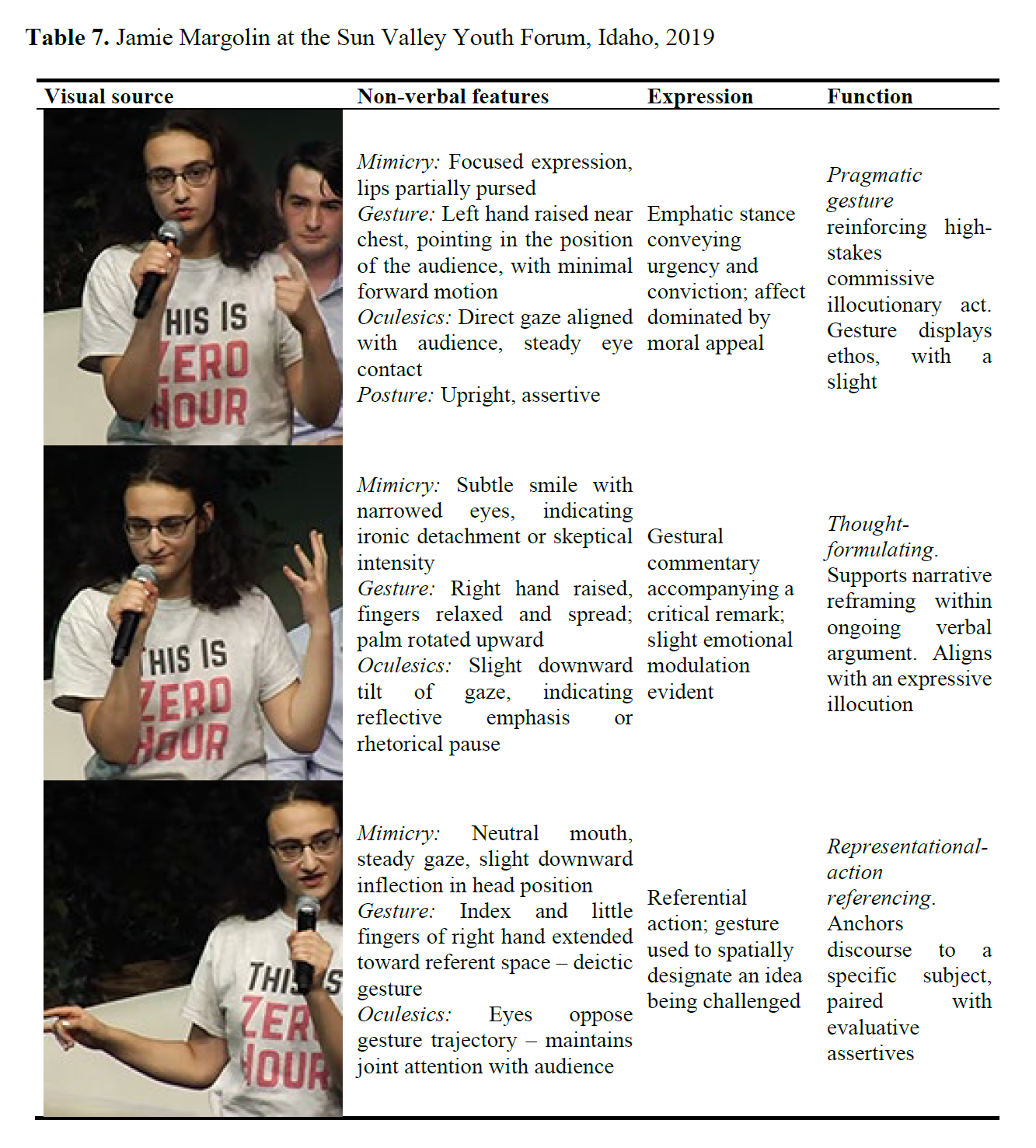

All nonverbal cues were annotated by combining close video observation with time-synchronized coding. We structured, as an examplar, one speech (described in Table 7 Closing Remarks by Jamie Margolin) as a comprehensive ELAN project to demonstrate the process in detail. In this fully annotated example, the coding is organized into multiple tiers: a base tier with the speech transcript segmented by illocutionary acts; a tier labeling each segment’s speech act type (according to Searle’s categories); a tier indicating the rhetorical appeal of that segment (ethos, pathos, or logos); and additional tiers capturing each multimodal signal – including the speaker’s facial expression, gaze direction, body posture, and each notable hand gesture aligned with the speech. Each gesture instance is further described and classified on a dedicated sub-tier (noting its form and its pragmatic function, such as a discourse-structuring motion or an action-referencing gesture). This ELAN-coded file (provided in the Supplementary materials [1]) illustrates how time codes and annotations were aligned (manually or automatically) with the video for precise multimodal analysis (the scheme is also provided in the Supplementary materials [2]).

For the remaining speeches in our corpus, we applied the same analytical criteria that were reflected in the examination of the full multi-tier ELAN files. We also employed a manual method prior to using the software – reviewing the videos and aligning notable gestures and other nonverbal cues with the corresponding transcript segments in our notes, which were analyzed according to our annotation scheme. The inclusion of a single, fully annotated ELAN example serves to enhance research transparency and allows for a clear understanding of how the multimodal coding was implemented in practice.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analysis

The multimodal analysis of the speakers’ performances is carried out to exemplify how the environmentalists instantiated the moves and performed the persuasive strategy drawing on verbal and non-verbal modes of communication. Specifically, we looked at the activists’ spoken mode, use of non-verbal means (i.e., images and realia), space (i.e., authoritative or interactive), and posture (dynamic or static). The findings reveal that the activists’ speech seem to raise listeners’ awareness and/or familiarize them with a new concept before setting up the activity. In doing so, activists can situate public in the context of the activity and begin to involve them. After completing the activity, the summary move serves to recapitulate, reinforce, and build new knowledge. Activists rely on different images and use a variety of means of expression during their performances in order to influence the audience.

Environmental discourse at the perlocutionary level can be presented by different strategies, in particular by raising awareness, confrontation, persuasion, mobilization, narration. Every strategy is aimed to correlate with certain tactics that are expressed at the locutionary and illocutionary levels. In this study, we focus on the persuasive strategy. Based on Aristotle’s "Rhetoric" we identify three parts reflecting major tactics as essential components of persuasive strategy (Rapp, 2023):

Ethos (credibility). This tactic refers to the character or ethical appeal of the speaker. This tactic establishes the credibility of what is being said and the authority of the speaker. Personal authority is observed when the speaker refers to his status, experience, or moral responsibility to build trust. For example, “I stand before you today representing my entire generation”, which reveals the speaker’s moral responsibility. Ethical appeals are established when the speaker demonstrates honesty or compliance with common values. For example, “I sued my state government in a lawsuit called Piper vs. The State of Washington along with 12 other youth plaintiffs, for contributing to the climate crisis <...>” (Jamie Margolin).

Pathos (emotion). This tactic appealing to the emotions of the audience, using evocative language that expresses the speaker’s sensual attitude. The speaker uses emotionally charged words to evoke feelings. The speaker shares personal anecdotes or stories that evoke an emotional response from the audience. For example, “I also remember when I was driving by El Rio Lerma. It’s the most polluted river in Mexico. And it’s right by my hometown” (Xiye Bastida). The speaker uses personal background to explain the motivation for activism.

Logos (logic). This tactic focuses on reasoning and evidentiary arguments to support a claim, often using facts, data, or logical conclusions. The speaker uses logical reasoning, such as causation or comparisons, to make his arguments. For example, “We must also bear in mind that these are just calculations. Estimations. That means that these ‘points of no return’ may occur a bit sooner or later than 2030" (Greta Thunberg). These inferences that illustrate the urgency and urgency of the problem.

3.2. Speech act analysis

At the illocutionary level we distinguish the following speech acts according to Searle’s model (Table 1): assertives (statements that convey information or describe reality), directives (requests, commands, or suggestions intended to induce action, commissives (commitments to future action), expressives (expressing an emotional state or attitude), declaratives (statements that create or change social reality).

Analysis of Greta Thunberg’s speeches reveals a balanced use of ethos, pathos, and logos, with a slight emphasis on pathos. This emotional appeal is primarily conveyed through assertives and expressives, enabling broad resonance while maintaining persuasive rationality. Correlation between locutionary and illocutionary levels indicates assertives dominate the logos and pathos sections, while expressives feature prominently in the ethos segments.

Jamie Margolin’s rhetoric is heavily saturated with pathos, also realized through assertives and expressives. At the locutionary-illocutionary levels, assertives predominate across all three rhetorical appeals, with expressives exclusively conveying her ethical appeal. This suggests Margolin primarily leverages emotional persuasion to communicate her message.

Xiye Bastida’s speeches are characterized by a strong ethos foundation, established through deeply personal engagement. Expressives, reflecting significant emotional involvement, are the dominant speech act within her pathos and ethos appeals. At the locutionary level, assertives occur more frequently than within her explicit logos appeals.

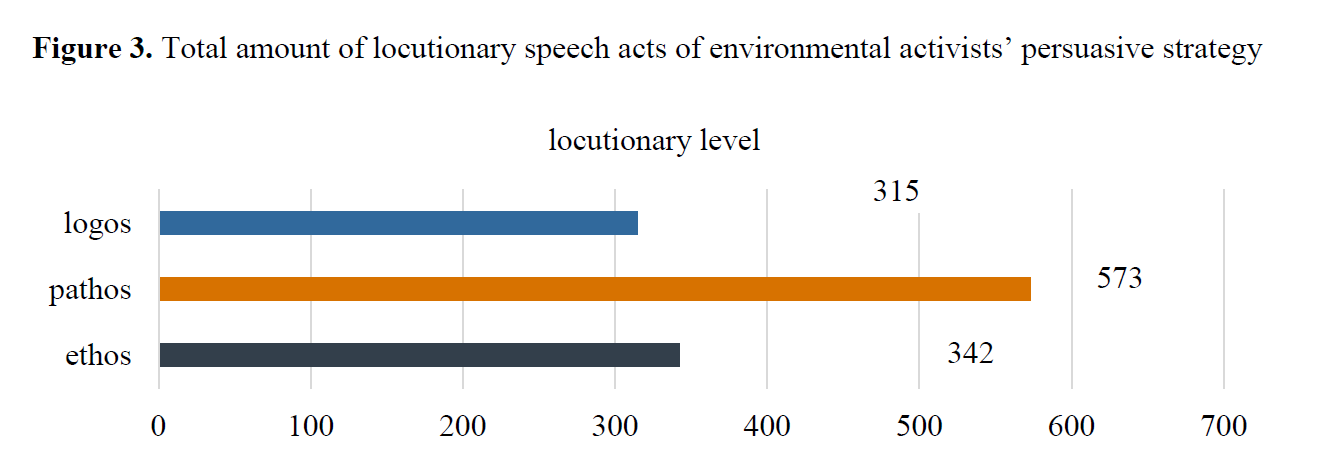

Collective analysis of all three activists indicates that pathos is the most prevalent persuasive tactic, while logos is the least utilized (Figure 3). This finding suggests that although evidence and argumentation hold importance in environmental discourse, emotional and ethical engagement often take precedence.

Furthermore, analysis at the illocutionary level reveals a clear hierarchy in the speech acts employed. Assertives predominate significantly, indicating that the foundational communicative strategy within this environmental discourse is the presentation of facts, claims, and information transfer. This emphasis on assertives aligns with the activists’ need to establish credibility and ground their urgent messages in perceived reality, particularly concerning scientific evidence and observable impacts of the climate crisis.

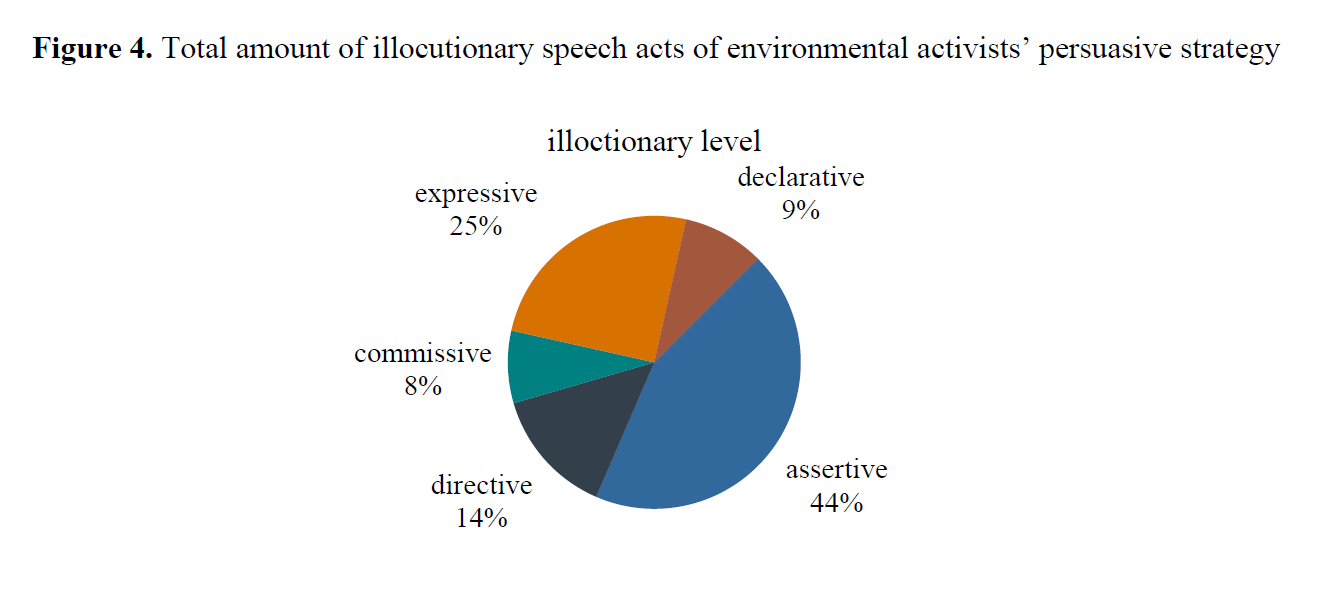

Expressives constitute the next most frequent category, serving to articulate the speakers’ personal emotional responses, deeply held values, and moral convictions. Their prevalence underscores how personal narrative and affective resonance are crucial for connecting with audiences and motivating engagement on an emotional level, complementing the factual basis provided by assertives (Figure 4).

Conversely, directives (attempts to get the audience to perform an action) and declaratives (statements that bring about a change in institutional reality) are notably scarce. This scarcity reflects the inherent positioning of youth activists within the broader socio-political environmental. Lacking formal institutional authority or direct legislative power, their primary role is not to command immediate action through directives or effect institutional change through declaratives. Instead, their persuasive power derives from raising awareness (assertives), building solidarity through shared feeling (expressives), and compelling moral witness – a role consistent with their status as activists mobilizing public opinion and demanding accountability from established power structures. The near absence of commissives (commitments by the speaker to future actions) further reinforces this dynamic, highlighting their focus on persuading others (audiences, governments, corporations) to act, rather than pledging actions solely within their own power to undertake.

3.3. Multimodal unit analysis

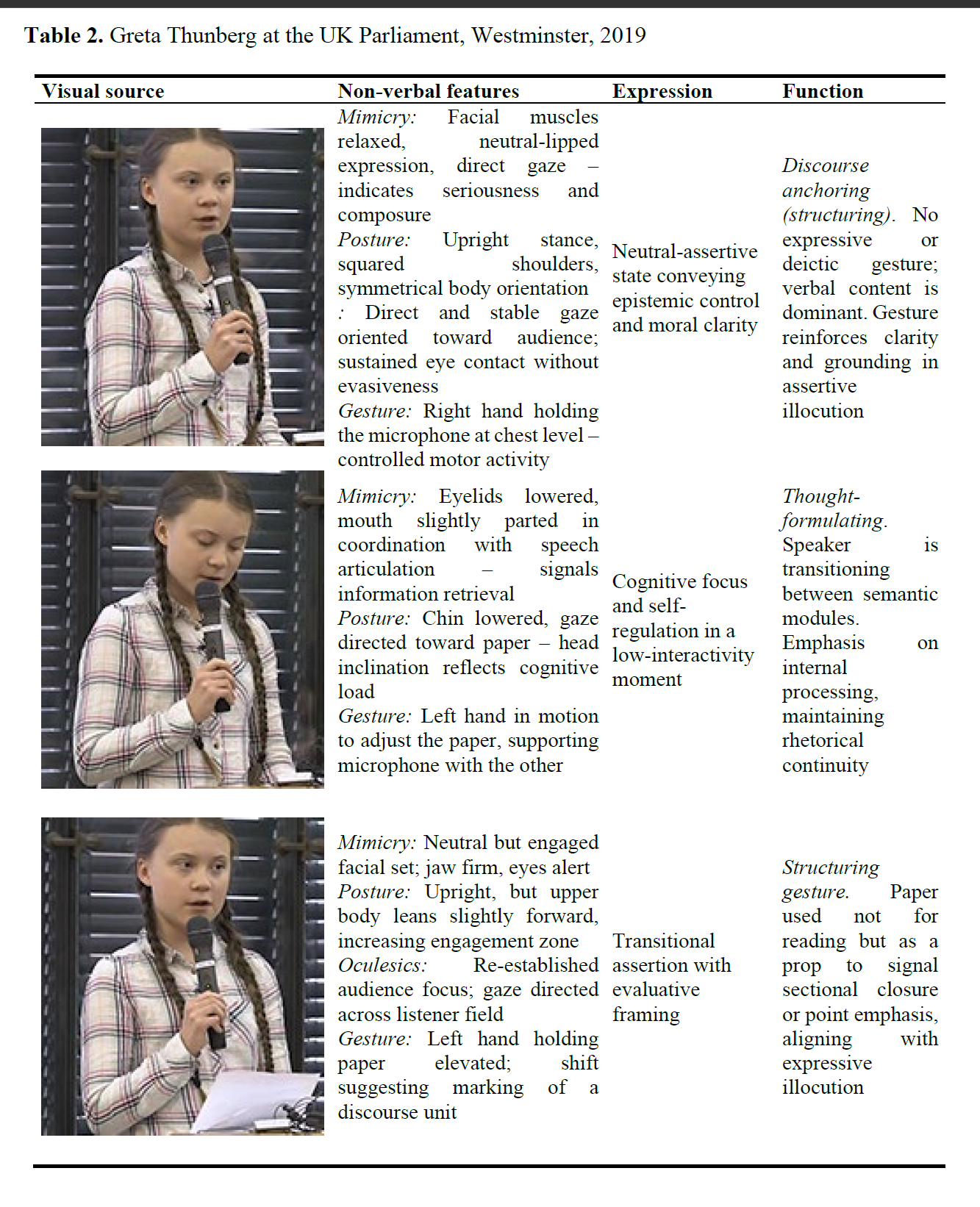

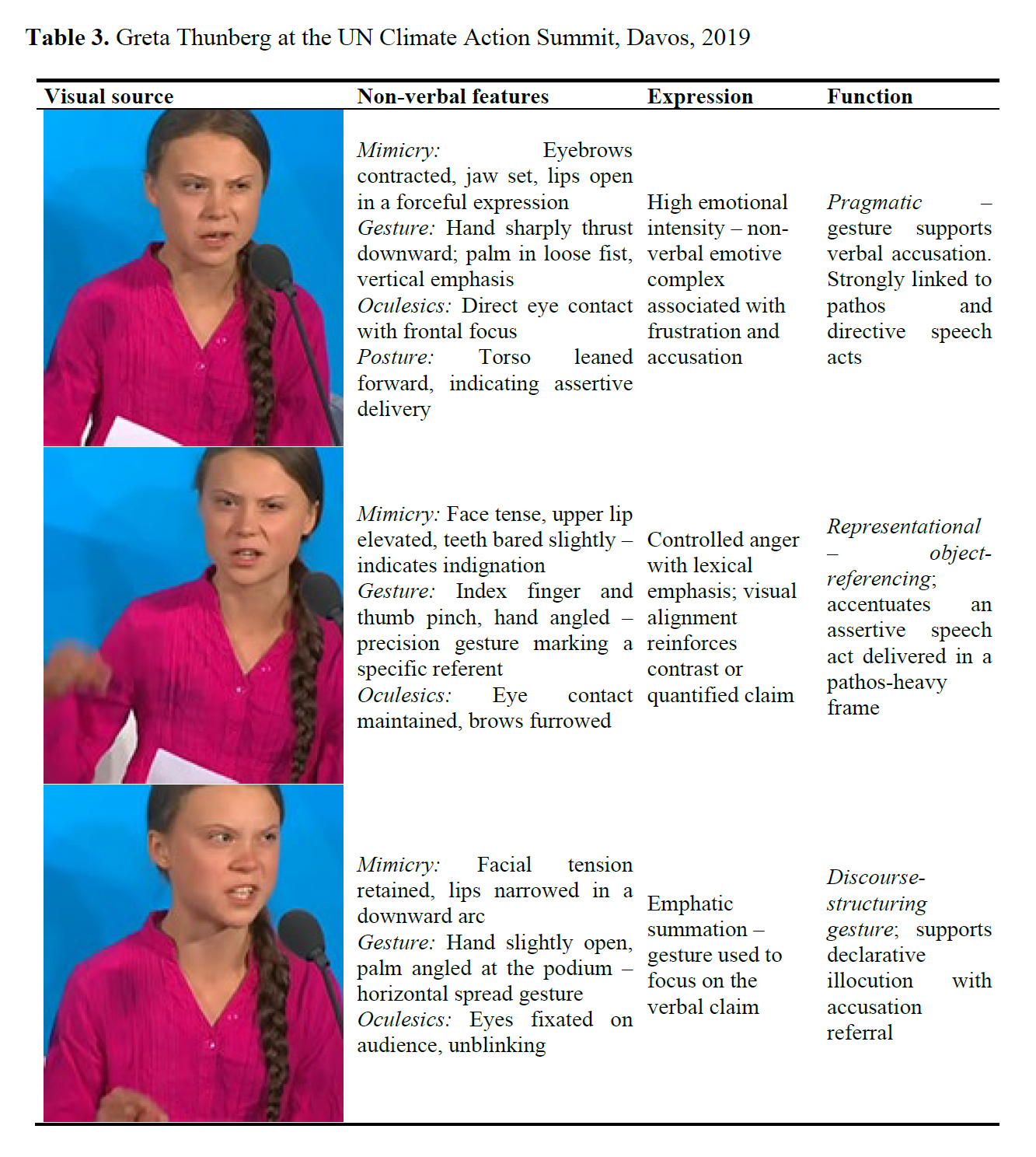

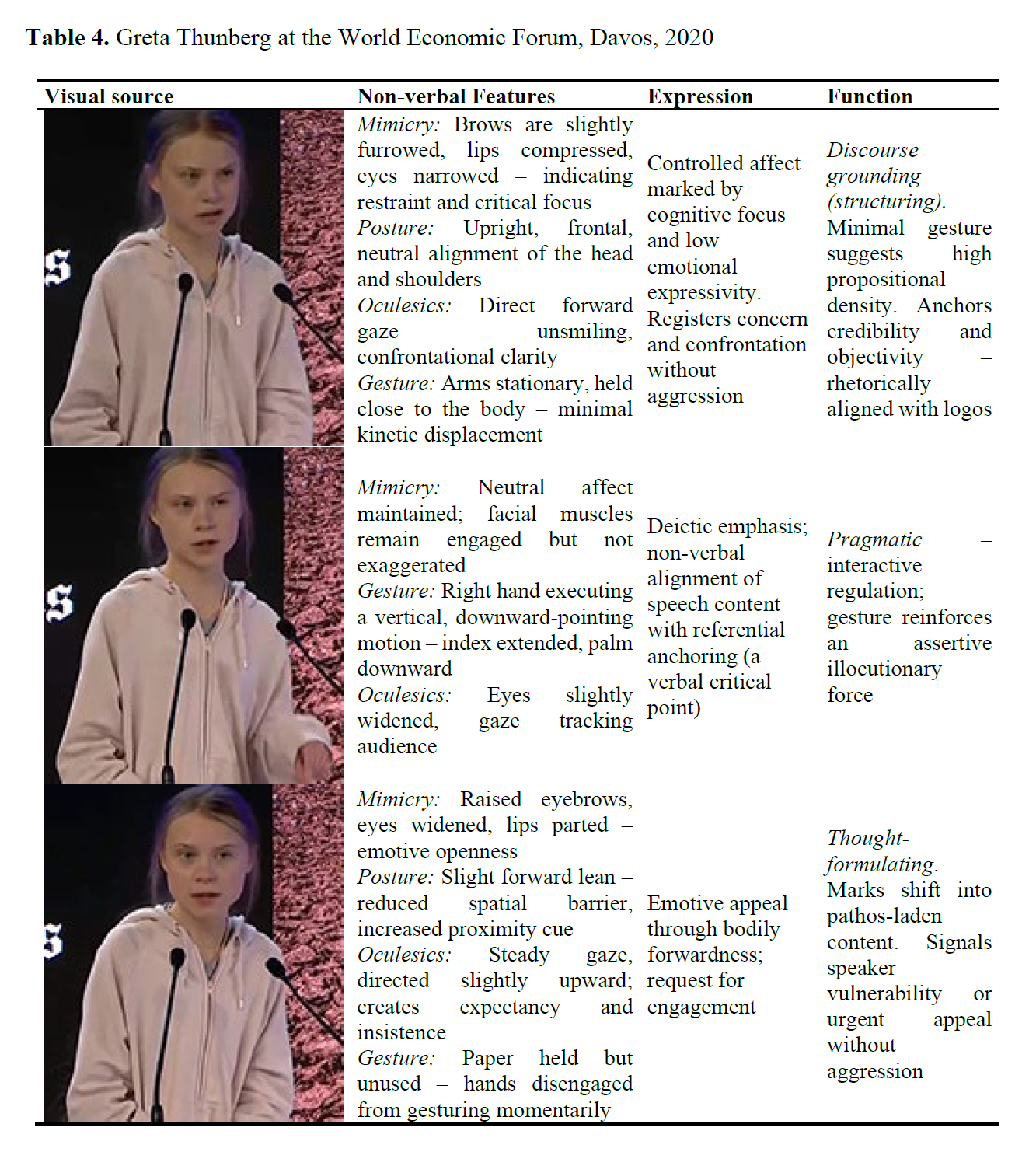

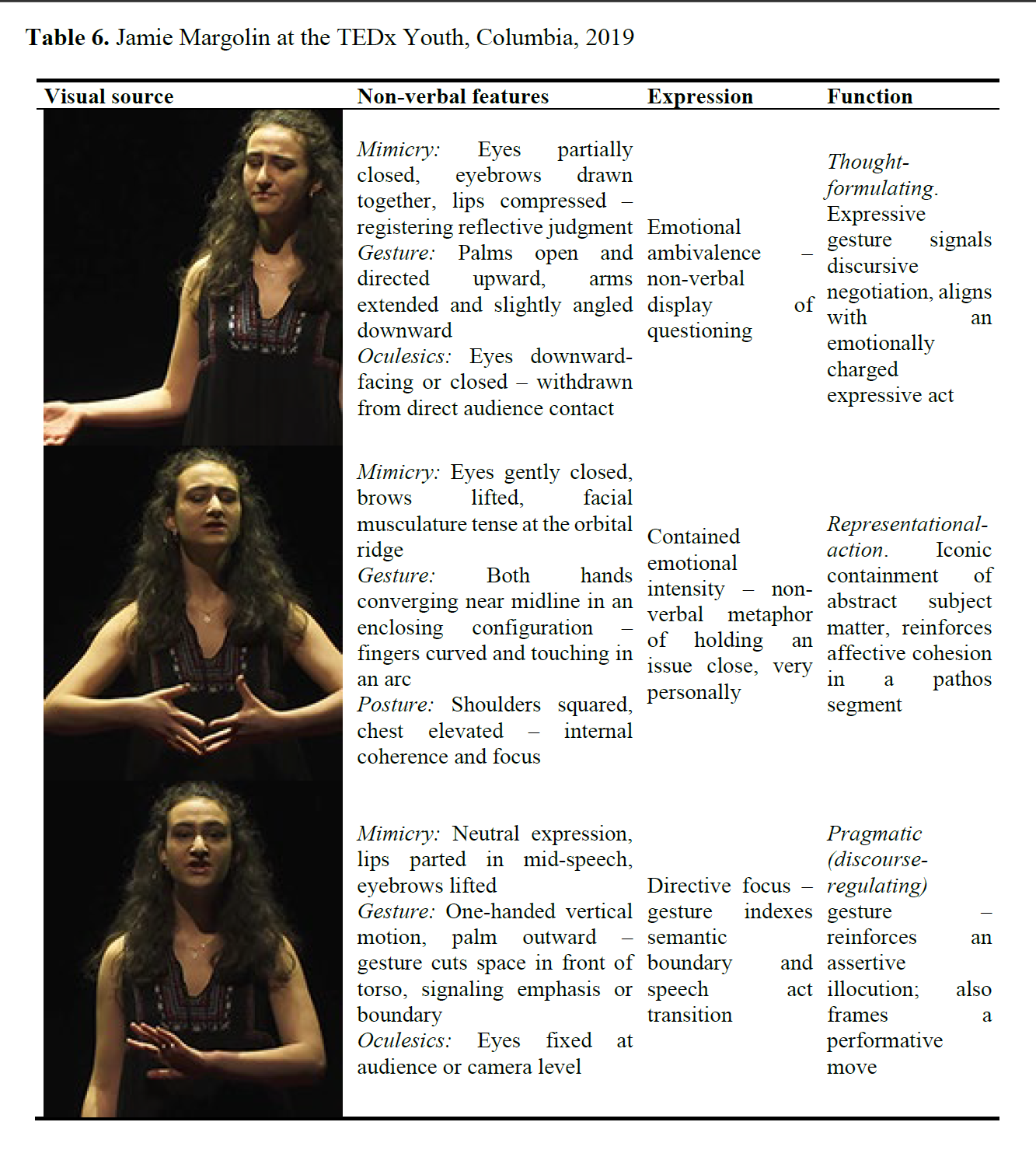

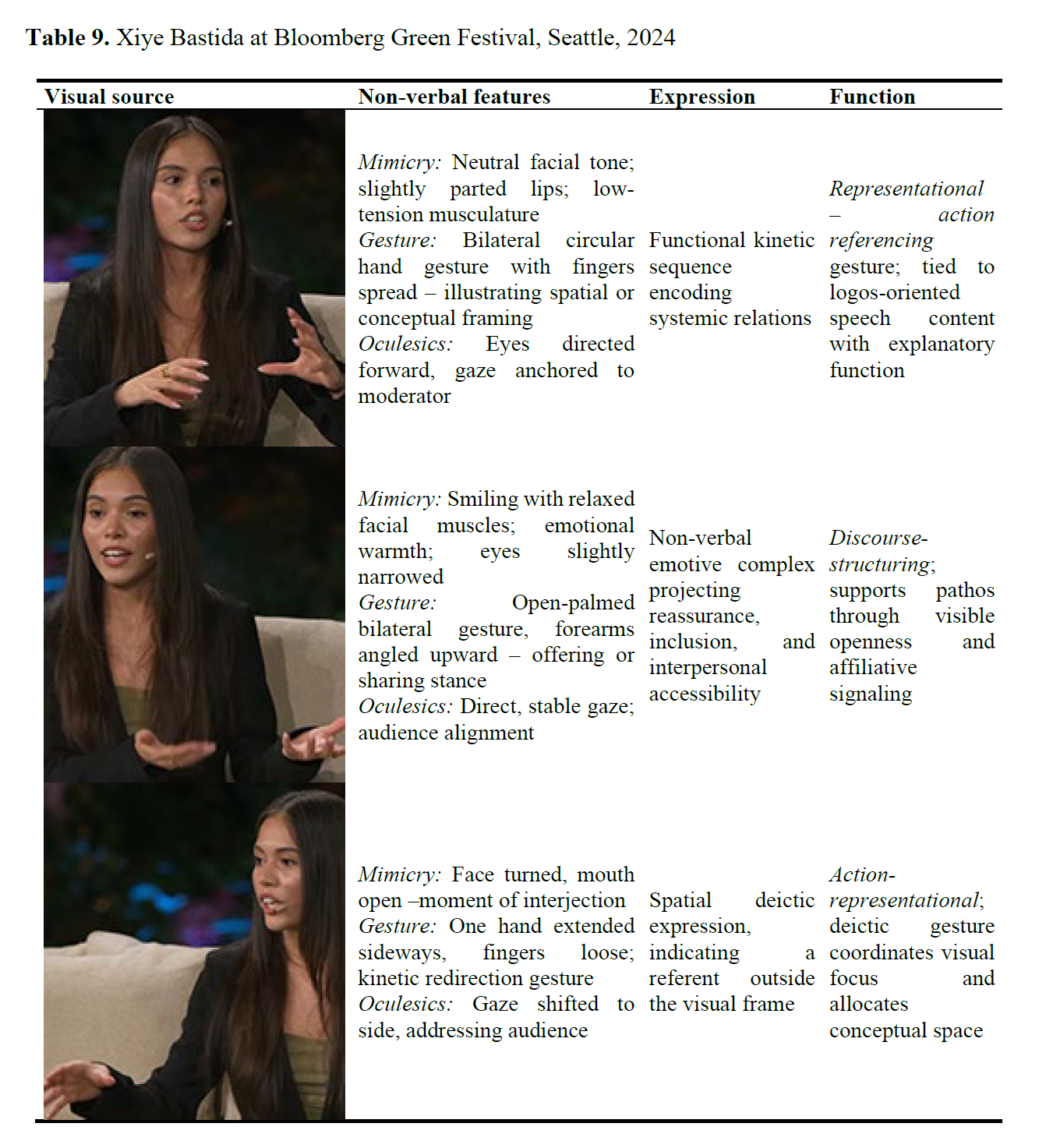

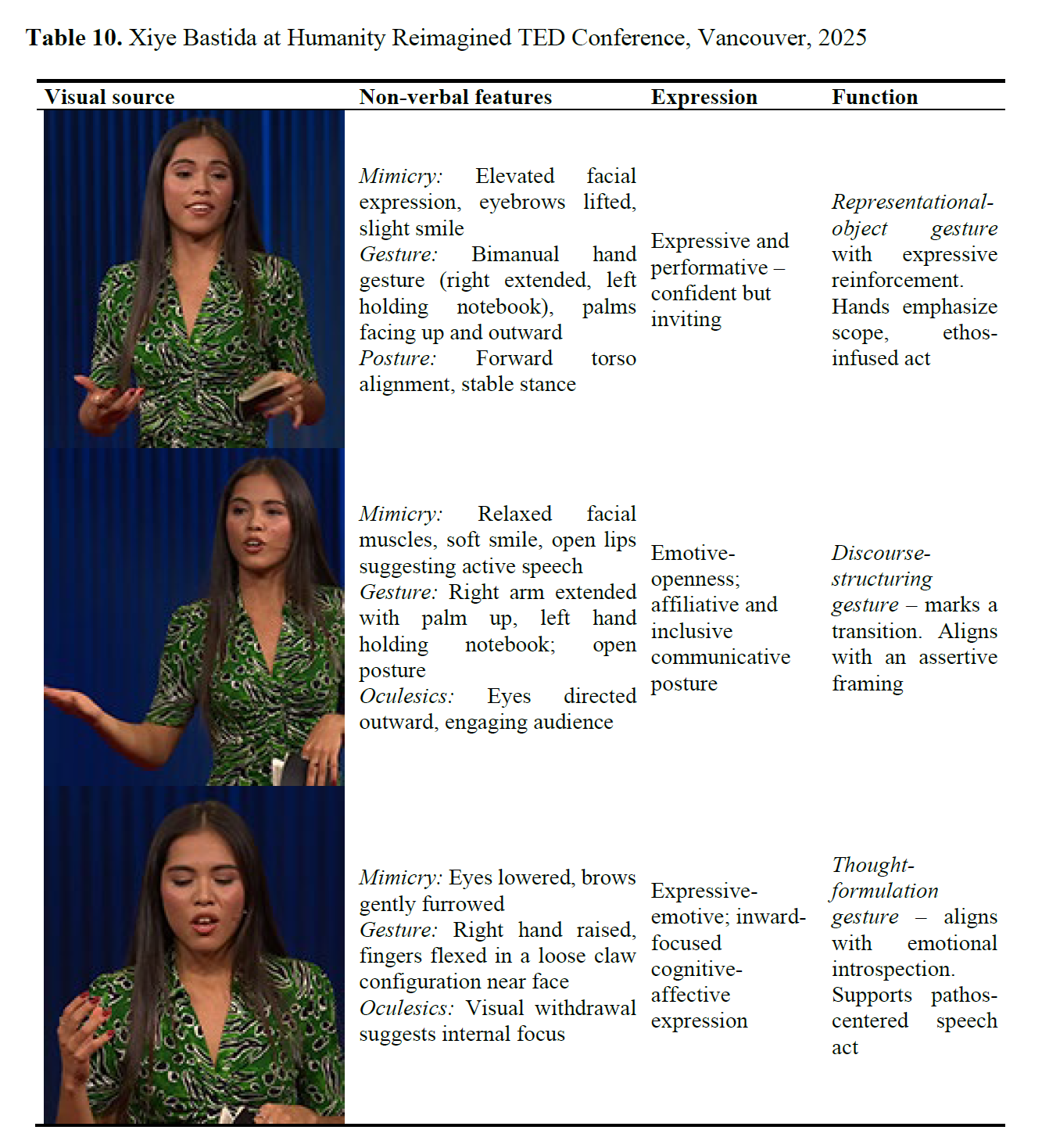

Applying semiotic principles, we recognize discourse as fundamentally multimodal, integrating both verbal and non-verbal elements. This perspective frames the linguistic personality as a multimodal unit – a subjective construct operating within culture’s meta-discursive space. The core of any discursive field is a synthetic linguistic personality, whose structure and evolution are governed by its cognitive-pragmatic programme (i.e., its knowledge systems and communicative strategies). Thus, the environmental activists’ speech and the synthetic linguistic personality realized in its space is a multi-subtextual formation (synthetic text) formed based on the fusion of verbal, articulatory and visual components. The following is a brief of each of the activists’ visual-functional representations, Greta Thunberg (Tables 2-4), Jamie Margolin (Tables 5-7), Xiye Batida (Tables 8-10).

From the 1230 analyzed speech acts, 172 multimodal units were found containing non-verbal couplings, categorized into multimodal channels.

These couplings were categorized by function as follows: structuring discourse (n=51) emerged as the most frequent, followed by pragmatic functions (n=44), formulating thoughts (n=27), object-representing gestures (n=29), and action-representing gestures (n=21). These findings confirm that gesture functions are contextually activated to reinforce rhetorical appeal. Specifically, the dominant structuring gestures emphasize message coherence and framing, while pragmatic gestures play a significant role in interaction regulation and highlighting speaker agency. Although representational gestures (object and action combined) were the least frequent category, they crucially anchor abstract discourse to concrete referents, significantly aiding audience comprehension.

In our results, we also note that the supplementary ELAN example provides a concrete illustration of these multimodal patterns. For instance, the fully annotated Margolin speech (see Supplementary materials) shows that a pathos-driven plea in her closing remarks is accentuated by an emphatic beat gesture, while a transition in topic is marked by a clear discourse-structuring hand motion. Such instances from the example demonstrate how gestures and speech acts are tightly coupled in practice, mirroring the broader trends identified in our quantitative analysis.

4. Discussion

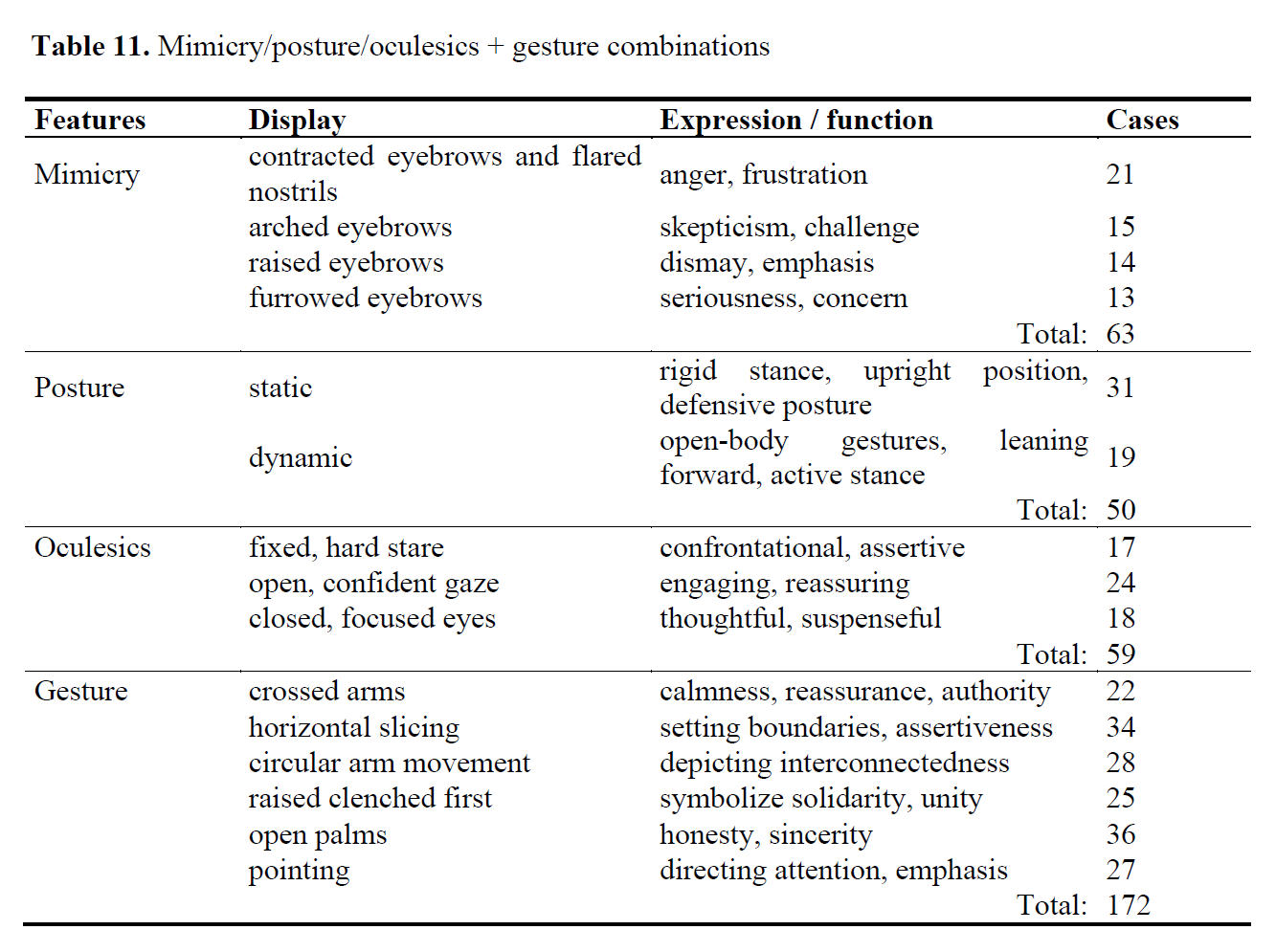

This study systematically analyzed multimodal markers – specifically mimicry, posture, oculesics, gestures, and facial expressions – in the public speeches and media appearances of prominent youth environmental activists, notably Greta Thunberg, Jamie Margolin, and Xiye Bastida. Quantitative analysis revealed notable patterns in multimodal behaviors that were closely aligned with rhetorical strategies identified by classical frameworks, notably Aristotle’s triad of ethos, pathos, and logos.

Of the total 1230 speech acts annotated, the data clearly indicated a dominance of pathos-based tactics (emotion-driven appeals), utilized frequently by all three activists (approximately 46% of the coded speech acts). This aligns with previous research highlighting emotional appeals as primary in activist discourse, often deployed to mobilize collective action and reinforce communal identity. Logical reasoning (logos) was the least utilized (approximately 26%), supporting the notion that environmental activism often prioritizes affective engagement over purely rational persuasion. Ethos appeals, emphasizing the credibility and ethical integrity of the speaker, accounted for the remainder (approximately 28%), reflecting the importance activists place on authenticity and moral positioning.

Multimodal analysis further refined these rhetorical insights. Structuring gestures (32% of total gestures) were the most frequent, emphasizing message coherence and framing. Pragmatic gestures (25%) regulated interactions and highlighted speaker agency. Representational gestures – combining object- and action-referencing – constituted 43% of gestures and served as the least frequent functional category, anchoring abstract discourse to concrete referents to aid audience comprehension.

Facial expressions and oculesics complemented gestures by reinforcing emotional and ethical appeals. Contracted eyebrows with flared nostrils (anger/frustration, 33%) and fixed, hard stares (confrontational, 29%) signaled intensity, while open, confident gazes (reassuring, 41%) reflected openness. Postural analysis revealed static stances (rigid/upright/defensive, 62%) were more prevalent than dynamic postures (leaning forward/open-body, 38%), underscoring assertions of moral clarity. Ekman and Friesen’s (1971) foundational research on facial expressions further supports our findings that emotional expressions significantly enhance the persuasive power of activist speech.

These multimodal behaviors collectively construct a synthetic linguistic persona that integrates verbal, gestural, and facial channels into a coherent persuasive identity. This finding supports theoretical perspectives in multimodal pragmatics emphasizing the inseparability of verbal and non-verbal channels in effective communication (Kendon, 2004; McNeill, 1992).

The strategic use of gestures to structure discourse and regulate interaction aligns with findings that such non-verbal cues facilitate listener comprehension and signal speaker credibility. Additionally, facial expressions conveying emotions like concern or determination contribute to the perceived authenticity of the speaker, a crucial factor in persuasive communication (Crible, Kosmala, 2025).

The integrated use of modalities can be observed directly in the annotated example. For example, in Margolin’s closing remarks, a steady gaze and upright posture co-occur with an assertive, ethos-laden statement, and are accompanied by a firm hand gesture – together these cues visibly reinforce her credibility and emotional resolve. This concrete case supports our argument that multimodal cues collectively bolster the speaker’s persuasive persona, by making the abstract patterns tangible in a real-world performance.

Furthermore, the integration of multimodal elements supports the construction of a coherent speaker identity, enhancing the overall impact of the message. This multimodal approach both reinforces the verbal message and engages the audience on multiple levels, increasing the likelihood of message retention and persuasion (Pflaeging, Stöckl, 2021).

In summary, the effective deployment of multimodal cues in these public speeches aligns with established markers of successful communication in pragmatics and multimodal discourse, underscoring their rhetorical efficacy.

However, the research acknowledges limitations related to the scope of the corpus, potential observer bias, and incomplete gesture classification frameworks. The dataset was relatively limited in scope (featuring speeches by only three activists), and while our gesture classification system is comprehensive, it may not capture every nuance of nonverbal behavior. These factors necessitate caution in interpreting our findings. The results should be considered exploratory and illustrative of a novel analytical approach; confirming the observed patterns will require larger-scale studies that employ more extensive multimodal coding and rigorous inter-annotator reliability protocols. Further research might extend quantitative gesture analysis to larger corpora and diverse demographic segments within activist communities, potentially integrating automated coding techniques for enhanced reliability and coverage. Future studies should also involve multiple annotators and report reliability statistics to strengthen the empirical claims – potentially using tools like motion-capture or automatic gesture recognition to aid consistency.

5. Conclusion

The analysis is based on a compact corpus and manual coding without formal inter-annotator reliability statistics, so the findings should be treated as exploratory and require confirmation on larger, independently annotated datasets in future work. The derived data suggest that multimodal resources – gestural, postural, mimic, and oculesics cues – are important components of environmental activists’ persuasive strategy. This integration consistently aligns with rhetorical intent, predominantly amplifying emotional (pathos) and ethical (ethos) appeals through dominant structuring gestures (organizing complex discourse) and pragmatic gestures (signaling speaker engagement). These initial findings demonstrate that developing pragmatic multimodal competence in activist oral speech constitutes a complex dynamic process of intellectual and creative activity – one requiring domain-specific knowledge, innovative problem-solving, and the continuous formation of novel communication systems through applied practice.

In sum, this research contributes empirical evidence to the field of multimodal pragmatics by demonstrating how speech act theory can be applied to real-world activist discourse in conjunction with gesture analysis. It highlights the distinctive communicative profile of youth climate activism – particularly the blend of ethical and emotional appeals with strategic gesture use – thereby extending our understanding of persuasive political communication in a new context.

In modern society’s attention economy – where publics require constant stimulation—this competence proves essential. While Aristotelian rhetoric idealizes an ethos-pathos-logos equilibrium, our analysis reveals that youth activists’ strategic prioritization of pathos (emotional resonance) over logos (logical argument), though deviating from classical norms, effectively broadens audience reach.

As the field of multimodal pragmatics rapidly expands – informing domains from corpus linguistics to education – our holistic methodology demonstrates how integrating semiotic modalities yields deeper understanding of embodied persuasive competence in a variety of contexts. Future research should apply advanced techniques such as motion-capture and facial action coding systems to validate these findings further and enhance statistical generalizability. Investigating the influence of audience demographics and speech settings (e.g., formal debates versus protests) on multimodal tactics remains a valuable avenue for future inquiry.

6. Supplementary materials

A fully annotated ELAN file for the speech described in Table 7 (Jamie Margolin’s Closing Remarks) is available in the online supplementary repository (GitHub). This file contains the complete tiered annotation as described in the text—including aligned transcripts, speech act labels, rhetorical appeal codes, and detailed annotations of facial expression, gaze, posture, and gestures with their functions. Readers can download this file to examine the multimodal coding in detail or to replicate the annotation process on comparable data. We also included an annotation scheme that describe how to replicate this setup step by step.

[2] https://github.com/DigitLingDept/Multimodal-Speech-Act-Environmental-Activists-ELAN/blob/main/annotation%20scheme.md

Reference lists

Abercrombie, D. (1968). Paralanguage, British Journal of Disorders of Communication, 3 (1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682826809011441(In English)

Barrero Salinas, A. F. (2023). J. L. Austin and John Searle on Speech Act Theory, The Collector, available at: www.thecollector.com/speech-act-theory-austin-and-searle (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

Beltrán-Planques, V. and Querol-Julián, M. (2018). English language learners’ spoken interaction: What a multimodal perspective reveals about pragmatic competence, System, 77, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.01.008(In English)

Birdwhistell, R. L. (2021). Introduction to Kinesics: An Annotation System for Analysis of Body Motion and Gesture, Hassell Street Press. (In English)

Bouchey, B., Castek, J. and Thygeson, J. (2021). Multimodal learning, SpringerBriefs in statistics, 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58948-6_3(In English)

Brügger, A., Gubler, M., Steentjes, K. and Capstick, S. B. (2020). Social identity and risk perception explain participation in the Swiss youth climate strikes, Sustainability, 12 (24), 10605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410605(In English)

Bucher, H. (2025). Insights into the black box of multimodal meaning-making: investigating the reception of multimodality empirically, Visual Communication, 24 (3), 543–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572251335833(In English)

Cambria, E. (2025). Pragmatics Processing, in Understanding Natural Language Understanding, Springer, 55–77. https://doi.org///10.1007/978-3-031-73974-3_4(In English)

Campoy-Cubillo, M. C. and Querol-Julián, M. (2021). Assessing multimodal listening comprehension through online informative videos: The operationalisation of a new listening Framework for ESP in Higher Education, in Multimodality in English Language Learning, 238–256. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003155300-17(In English)

Cienki, A. (2013). Gesture, Space, Grammar, and Cognition, in Auer, P., Hilpert, M., Stukenbrock, A., Szmrecsanyi, B. (eds.) Space in Language and Linguistics, De Gruyter, 667–686. (In English)

Cornelio, G. S., Martorell, S. and Ardèvol, E. (2024). "My goal is to make sustainability mainstream": emerging visual narratives on the environmental crisis on Instagram, Frontiers in Communication, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1265466(In English)

Cox, R. (2013). Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere, SAGE. (In English)

Crible, L. and Kosmala, L. (2025). Multimodal pragmatic markers of feedback in dialogue. Languages, 10 (6), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10060117(In English)

Dicerto, S. (2018). Multimodal Meaning in Context: Pragmatics, in Multimodal Pragmatics and Translation: A New Model for Source Text Analysis, Springer, 37–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69344-6_3(In English)

Doyle, J. (2012). Here Today: Thoughts on Communicating Climate Change, available at: https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/21389609/HereTodayThoughtsOnCommunicatingClimateChange_JulieDoyle.pdf (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

Duchak, O. (2014): Visual literacy in educational practice, Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal, 6/2, 41–48. DOI: 10.2478/cphpj-2014-0017 (In English)

Ekman, P. and Friesen, W. (1971). Constants across Cultures in the Face and Emotion, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17 (2), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030377(In English)

Enfield, N. J. (2009). The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture, and Composite Utterances, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511576737(In English)

Fang, Y. (2023). Review of Corpus Pragmatics, Corpus Pragmatics, 7, 401–404. DOI: 10.1007/S41701-023-00149-8(In English)

Freigang, F., Klett, S. and Kopp , S. (2017). Pragmatic Multimodality: Effects of Nonverbal Cues of Focus and Certainty in a Virtual Human, in Intelligent Virtual Agents, Springer, 142–155, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67401-8_16(In English)

Goodwin, C. (2017). Co-Operative Action. Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139016735(In English)

Haryanti, P., Saddhono, K. and Anindyarini, A. (2023). Multimodal as a New Perspective in Pragmatics in the Digital Era: Literature Review. International Conference of Humanities and Social Science (ICHSS), 494–501, available at: https://www.programdoktorpbiuns.org/index.php/proceedings/article/view/319 (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

Hömke, P., Holler, J. and Levinson, S. C. (2018). Eye blinks are perceived as communicative signals in human face-to-face interaction, PLoS ONE, 13 (12), e0208030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208030(In English)

Huang, L. (2021). Toward Multimodal Corpus Pragmatics: Rationale, Case, and Agenda. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 36, 101–114, https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz080(In English)

Interaction Design Foundation — IxDF (2016). The Persuasion Triad – Aristotle Still Teaches, available at: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/the-persuasion-triad-aristotle-still-teaches (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

Iriskhanova, O. K. (2022). Multimodal Discourse Study, Studia Philologica, Moscow, Russia. (In Russian)

Jewitt, C. (ed.) (2023). The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, 2nd ed., Routledge. (In English)

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, Literacy, and Learning: A Multimodal Approach, Routledge. (In English)

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance, Cambridge UK. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807572(In English)

Kendrick, K. H. (2015). The intersection of turn-taking and repair: the timing of other-initiations of repair in conversation, Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00250(In English)

Kibrik, A. and El’bert, E. (2008). Understanding Spoken Discourse: The Contribution of Three In-formation Channels. Third International Conference on Cognitive Science, IP RAN, 82–84, available at: https://iling-ran.ru/kibrik/Information_channels@CogSci2008.pdf (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

Kress, G. (2009). Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communica-tion. Routledge. (In English)

Landis, J. R. and Koch, G. G. (1977). The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics, 33 (1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310(In English)

Lei, H. and Zhang, L. (2022). Development and Application of a Multimodal Corpus for Learn-ers’ Pragmatic Competence, Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 40, 378–380. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2022.2037443(In English)

Levinson, S. C. (2016). Speech acts, in The Oxford Handbook of Pragmatics, Oxford University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697960.013.22(In English)

Lim, F. V. (2020). Designing Learning with Embodied Teaching, Routledge eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429353178(In English)

Loos, C., German, A. and Meier, R. P. (2022). Simultaneous structures in sign languages: Acquisition and emergence, Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992589(In English)

Machin, D. and Mayr, A. (2012). How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction, Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781036212933(In English)

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal about Thought, The University of Chicago Press. (In English)

Miller, L. B. (2025). From Persuasion Theory to Climate Action: Insights and Future Directions for Increasing Climate-Friendly Behavior, Sustainability, 17 (7), 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072832(In English)

Morell, T. (2018). Multimodal competence and effective interactive lecturing, System, 77, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.12.006(In English)

Müller, C. (1998). Speech Related Gestures: History, Culture, Theory of Language, Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag. (In German)

Müller, C., Cienki, A., Fricke, E., Ladewig, S., McNeill, D., Bressem, J. (2023). Body – Language – Communication: An International Handbook on Multimodality in Human Interaction, De Gruyter Mouton. (In English)

Norris, Si (ed.) (2012). Multimodality in Practice: Investigating Theory-in-Practice through. Methodology, Routledge Studies in Multimodality Book Series. (In English)

Norte Fernández-Pacheco, N. (2016). The orchestration of modes and EFL audio-visual comprehension: A multimodal discourse analysis of vodcasts. Dialnet, available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/dctes?codigo=59286 (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

O’Callaghan, K. A., Nunn, P. D., Casey, S., Crimmins, G. and Dugmore, H. (2025). Speaking of climate change: Reframing effective communication for greater impact, Climate, 13 (4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13040069(In English)

Pflaeging, J and Stöckl, H. (2021). The Rhetoric of Multimodal Communication, Visual Communication, 20 (3), 319–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/14703572211010200(In English)

Rapp, C. (2023). Aristotle’s Rhetoric. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-rhetoric (Accessed 28 June 2025) (In English)

Russell, J. A. (1995). Facial expressions of emotion: What lies beyond minimal universality? Psychological Bulletin, 118 (3), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.379(In English)

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139173438(In English)

Sidiropoulou, M. (2020). Understanding Migration through Translating the Multimodal Code, Journal of Pragmatics, 170, 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.020(In English)

Tindale, C. W. (2004). Rhetorical Argumentation: Principles of Theory and Practice, Sage. (In English)