SOFT-BOILED SPEECH: A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF EUPHEMISMS IN ALGERIAN AND JORDANIAN ARABIC

Abstract

The present contrastive study is geared mainly towards probing into the euphemistic language that Algerian and Jordanian Arabic speakers resort to when certain tabooed topics and concepts are brought to the fore. Intriguingly, such an analysis was done in the light of Brown and Levinson's Politeness Theory. To this end, the data were elicited by dint of two questionnaires which were prepared by first collecting the needed euphemisms from the native speakers of the two dialects under scrutiny. The first one was handed to a randomly chosen sample of 100 Algerian BA students of English at the University of Mohammed Seddik Ben Yahia, Jijel. The second one, however, was given to a randomly chosen sample of 100 Jordanian BA students of English at the University of Jordan. The findings indicate that euphemism is both a linguistic as well as a cultural phenomenon. Accordingly, despite highlighting some similarities between the two cultures under scrutiny in the use of euphemistic terms and expressions, one to one correspondence does not exist. Therefore, taking cognizance of euphemisms in different cultures is a sine qua non for facilitating intercultural communication.

Keywords: Algerian Arabic, Euphemism, Intercultural Communication, Jordanian Arabic, Politeness Theory

1. Introduction

For the sake of politeness or pleasantness, broaching some topics or referring to certain concepts necessitates making recourse to some safeguards that are embedded differently in different languages and language varieties. Euphemisms- courteous ways of referring to tabooed terms and topics- could be those safeguards when sensitive topics are brought into prominence. For example, to describe children of low intelligence, people use “a bit slow for his age”, “Less able” or “under achiever”, etc. If someone has died, he is thought of as having “passed away”, and those who are handicapped or disabled are named politely as “differently-abled”. A "homeless person" is euphemized by “on the streets" while abortion is euphemistically referred to as “pregnancy termination”. These mild expressions are found in all cultures and they are “a universal feature of language usage” (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p.216). That is, they exist in every language and no human communication is without euphemisms. However, a particular utterance which is polite in one culture might be impolite in another culture. Therefore, taking cognizance of euphemisms in different cultures is a sine qua non for facilitating intercultural communication.

As a matter of fact, euphemistic words and expressions embody human being’s desire to extricate themselves from barbarism and to become civilized creatures. Hence, it should be noted that they are inextricably linked to politeness. Particularly, their use is in conformity with Brown and Levinson’s Politeness Theory. The latter revolves around the notion of face which they succinctly defined as “the public self-image that every member wants to claim for himself…Thus, face is something that is emotionally invested, and that can be lost, maintained, or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction” (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 61). They considerer face as a coin with two interrelated sides viz: positive face and negative face. The former entails “the positive consistent self-image or ‘personality’ (crucially including the desire that this self-image be appreciated and approved of) claimed by interactants” while the latter incorporates “the basic claim to territories, personal preserves, rights to non-distraction-i.e. to freedom of action and freedom from imposition”( Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 61).

Therefore, the main premise of the Politeness Theory is that speakers try to avoid threatening the face of those they address by dint of various forms of indirectness, an instance of which is the so-called "euphemisms". Following this line of reasoning, Allan and Burridge (1991: 14) assert that "a euphemism is used as an alternative to a dispreferred expression, in order to avoid possible loss of face: either one's own face, or through giving offence, that of the audience, or of some third party". The gist is that the interlocutors resort to using euphemistic expressions either to minimize threat to the addressee’s face or to minimize threat to their own face.

Axiomatically, defining the concept of euphemism has gained the attention of different researchers since time immemorial. , As a result, a plethora of definitions have been provided for it. In a nutshell, the word euphemism originated in the Greek language. Accordingly, the Online Etymology Dictionary defines a euphemism as “1650s, from Greek euphemismos "use of a favorable word in place of an inauspicious one," from euphemizein "speak with fair words, use words of good omen," from eu-“good, well” (see eu-) + pheme "speaking," from phanai "speak". In this regard, McArthur (1992, p. 387) states that a euphemism in rhetoric is “the use of a mild, comforting, or evasive expression that takes the place of one that is taboo, negative, offensive, or too direct: Gosh God, terminate kill, sleep with have sex with, pass water, relieve oneself urinate”. In a similar vein, there are other definitions of euphemism which are also based in one way or another on the notion of indirectness: ‘‘a mild or roundabout word or expression used instead of a more direct word or expression to make one's language delicate and inoffensive even to a squeamish person’’ (Willis & Klammer, 1981,p.192–193). Also, Al-Qarni and Rabab’ah (2012, p.730) maintain that euphemism is a universal phenomenon which could be succinctly elucidated as “a polite or indirect way of saying a tabooed term”. Following the same line of reasoning, Rawson (1981, p.1) asserts that euphemisms are “mild, agreeable, or roundabout words used in place of coarse, painful, or offensive ones. The term comes from the Greek eu, meaning "well" or "sounding good," and phêmê, "speech"”.

As is clear, euphemisms are worthy of the controversy that their study has engendered. Therefore, for the sake of efficiency in handling the matter at hand, the present research work raises the following overarching questions:

- What euphemisms do Algerian and Jordanian Arabic speakers use to refer to each of the following topics: Death, sickness, and cancer, and to certain places, jobs, and terms of address?

- What are the main similarities and differences between Algerian and Jordanian Arabic speakers in the use of euphemisms?

- Do the differences in using these euphemisms result from having two different cultures?

2. Literature Review

Following the emergence of contrastive analysis under the leadership of Robert Lado, researchers in the field of contrastive linguistics have hastened to compare languages with regard to their sound systems, grammatical structures, writing systems, cultures and vocabulary systems. Apparently, Arab researchers are no exception. Accordingly, Arabic-English contrastive studies started to dominate the scene of contrastive linguistics in the late 1950’s of the twentieth century. This was in conformity with developments in contrastive analysis studies in Europe and the U.S.A. During their first phase, Arabic-English contrastive studies were characterized by their “pedagogic orientation and decontextualization of linguistic data” (Mukattach 2001: 116). However, they had a brand new direction which was unavoidable due to the dominant developments in linguistic theory at the time. Thus, they changed from having a pedagogic orientation to joining the realm of theoretical contrastive studies. However, having a myriad of contrastive studies which contrast the lexis of two varieties of the same language, and thus two cultures, is still something to be desired.

Qi (2010) attempted a contrastive analysis of the cultural differences in Chinese and English Euphemisms by means of the relevant linguistic theories. Thus, he concluded that euphemism is a linguistic, and particularly a cultural phenomenon and its development is the outcome of various socio-psychological factors. Importantly, the researcher maintained that such a study would surely shed light on the English teaching in China in the sense that in the teaching of English vocabulary, it is necessary for teachers to draw students’ attention to the understanding and use of those words and expressions with strong cultural connotations; teachers may as well make a bilingual comparison and contrast of such words and expressions, especially those which are not bad in the dictionaries but are to be avoided in the eyes of the British and Americans.

In another seminal study, Al-Azzeh (2010) gave special emphasis to the use of euphemisms by Jordanian speakers of Arabic. In this regard, she investigated meticulously the most common euphemisms Jordanian Arabic speakers use to refer to tabooed words, topics and concepts in their daily communication. In doing so, she examined the effect of social variables such as, the dialectal variety, gender and age on the use of euphemism in the Jordanian society in the light of the Politeness Principle and Context Theory.

Following similar lines of inquiry, Qanbar (2011) conducted a sociolinguistic study of the linguistic taboos in the Yemeni society and the strategies used by the Yemeni speakers to avoid the use of these words through different types of replacement of taboo words with more acceptable words such as euphemisms. Such a practice is conditioned by the cultural and religious norms of the society. It also offers an explanation as to why certain words are considered taboos in the society and why certain taboo words are accompanied by particular conventionally-fixed words. Intriguingly, this study used the politeness approach proposed by Brown and Levinson (1978, 1987) as the theoretical framework for the analysis of linguistic taboos in the Yemeni society.

Al-Qarni and Rabab’ah (2012) probed into the similarities and the differences between euphemism strategies that are used in Saudi Arabic and English and the way they are linked to cultural and religious beliefs and values. The researchers concluded that the strategies of euphemism found in the Saudi responses are ‘part-for-whole’, ‘overstatement’, ‘understatement’, ‘deletion’, ‘metaphor’, ‘general-for-specific’, and ‘learned words and jargons’. The British participants, however, employed ‘understatement’, ‘deletion’, ‘learned words and jargons’, ‘metaphors’, and ‘general-for specific’. Thus, Saudi Arabic was found to have more ways of expressing euphemisms. Another significant finding was that the Saudis and the British resort to taboos when handling death and lying, but hardly ever for bodily functions.

Importantly, Gomaa and Shi (2012) geared their study towards the investigation of the euphemistic language of death in Egyptian Arabic and Chinese. They found out that euphemisms are universal since they exist in every language and no human communication is without euphemisms. Both Egyptian and Chinese native speakers regard the topic of death as a taboo. Therefore, they handle it with care. Though Egyptian Arabic and Chinese employ euphemistic expressions to avoid mentioning the topic of death, Chinese has a large number of death euphemisms as compared with the Egyptian Arabic ones. The results also showed that death euphemisms are structurally and basically employed in both Egyptian Arabic and Chinese in metonymy as a linguistic device and a figure of speech. Moreover, they employed conceptual metaphor to substitute the taboo topic of death.

In a more recent study, Ghounane (2014) shed light on the dark side of Algerian culture in relation to language use via investigating linguistic taboos and euphemistic usage. The researcher showed that the attitudes of Algerian speakers are linked to certain socio-cultural and psychological factors including the social norms of the society, the social upbringing of its individuals and the social environment in which they get in contact in addition to their identity construction and other parameters. It was also found that Algerian people have developed a rich vocabulary which includes euphemistic substitutions. These substitutions are the results of societal, psychological and cultural pressures.

3. Methodology

The primary informants of the data are the first and the second authors who are native speakers of Algerian Arabic and Jordanian Arabic respectively. However, this was also supplemented by consulting several other native- speaker respondents who gave a hand by providing more examples of euphemisms so as to help in the preparation of the two questionnaires. Accordingly, the first questionnaire was administered to a randomly chosen sample of 100 Algerian BA students of English at the University of Mohammed Seddik Ben Yahia, Jijel. The second one, however, was given to a randomly chosen sample of 100 Jordanian BA students of English at the University of Jordan. Intriguingly, the differences in euphemistic language use that relate to some variables including gender were overlooked in the present study.

4.Results and Discussion

The findings of the study are presented and discussed in three sub-sections viz: (1) The Analysis of Algerian Arabic Data, (2) The Analysis of Jordanian Arabic Data, and (3) Contrasting Algerian and Jordanian Arabic Data.

- The Analysis of Algerian Arabic Data

- Algerian Arabic Euphemisms for Death, Sickness, and Cancer

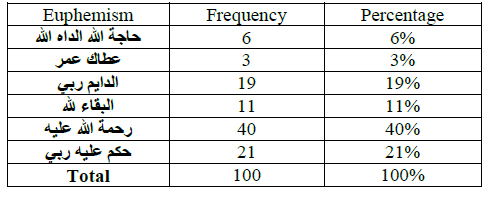

Frequency tables and percentages were established to see the extent to which each euphemism was used by Algerians to refer to the following taboo topics: death, sickness, and cancer respectively. Tables 1, 2, and 3 are a case in point.

Table1. Frequencies and Percentages of Death Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

As it is plainly displayed in table 1, the Algerian euphemized expression for death with the highest percentage was رحمة الله عليه (40%). This was followed by حكم عليه ربي, with a percentage equals to 21%. In addition, 19% of the respondents admitted that they used الدايم ربي. However, the percentage representing the use of البقاء لله was 11%. Lower percentages were occupied by حاجة الله الداه الله and عطاك عمر with the values 6% and 3% respectively.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

ماقادرش | 29 | 29% |

مريض | 10 | 10% |

عيان | 3 | 3% |

تعبان شوي | 7 | 7% |

معلول | 8 | 8% |

غلبان | 2 | 2% |

كما حب ربي | 6 | 6% |

في حالة | 28 | 28% |

فلفراش | 7 | 7% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 2. Frequencies and Percentages of Sickness Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

Dealing with the topic of sickness seems to have classified the euphemisms used by Algerian respondents according to their frequency of use from the highest to the lowest as follows: ماقادرش (29%), في حالة (28%), مريض (10%), معلول (8%), with تعبان شوي and فلفراش having the same percentage (7%), كما حب ربي (6%), عيان(3%), and غلبان (2%).

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

القونصير | 10 | 10% |

المرض ليمامليحش | 30 | 30% |

المرض الخامج | 7 | 7% |

هداك المرض | 15 | 15% |

المرض ليمايتسماش | 18 | 18% |

هداك المرض عافانا الله | 20 | 20% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 3. Frequencies and Percentages of Cancer Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

According to the responses obtained in table 3, a great percentage of the respondents (30%) used المرض ليمامليحش to refer to cancer. The euphemism هداك المرض عافانا الله had the second percentage 20%. The third position was recorded for المرض ليمايتسماش : 18%. Lower frequencies, however, were recorded for هداك المرض, القونصير and المرض الخامجwith frequencies of 15 , 10 and 7 respectively.

- Algerian Arabic Euphemisms for Jobs, Places and Terms of Address

The second question in the present research work is devoted to the euphemisms that were used to refer to some concepts such as certain places, jobs, and ways of naming and addressing in Algerian Arabic. Tables from 4 through 15 show the results of each concept and the distribution of their frequencies and percentages according to the number of participants for each concept.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

المقبرة | 25 | 25% |

المدفن | 9 | 9% |

الجبانة | 66 | 66% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 4. Frequencies and Percentages of Cemetery Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

A considerable number of respondents (66) reported using the euphemism الجبانة. The second position was represented by the term المقبرة : 25. Apparently, the least used term by Algerians was discovered to be المدفن : 9.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

السجن | 8 | 8% |

الحبس | 45 | 45% |

السيلون | 32 | 32% |

مركز الاصلاح الاجتماعي | 4 | 4% |

بوهدمة | 11 | 11% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 5. Frequencies and Percentages of Prison Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

Table 5 indicates that almost have of the informants (45%) made recourse to the euphemism الحبس. The euphemized expression السيلون had the second rank with a percentage of 32%. Less frequencies of use were recorded for بوهدمة : 11%, السجن 8%, and مركز الاصلاح الاجتماعي 4%.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

بيت لعزا | 18 | %18 |

دار لعزا | 25 | %25 |

نروح عند موالين الميت | 57 | %57 |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 6. Frequencies and Percentages of the Place of Memorial Ceremony Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

The findings in table 6 are an indication that نروح عند موالين الميت was the most frequently used euphemistic expression among Algerian speakers: %57. A quarter of them (%25) used دار لعزا whereas only %18 used بيت لعزا.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

البوباليسث | 15 | 15% |

عامل النظافة | 40 | 40% |

ليكاينظف | 45 | 45% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 7. Frequencies and Percentages of Garbage Man Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

According to table 7, ليكاينظف ranked first 45%, followed by the terms عامل النظافة 40%, and البوباليسث 15%.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

لمره | 42 | 42% |

المادام | 16 | 16% |

المخلوقة | 9 | 9% |

العايلة | 6 | 6% |

أم لولاد | 20 | 20% |

السيدة | 5 | 5% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 8. Frequencies and Percentages of Woman Naming Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

According to the responses obtained, the euphemism لمره occupied the first position by being represented with a percentage of 42%. The second highest position was represented by أم لولاد :20%. Closer to the latter in percentage was المادام : 16%. Finally, المخلوقة (9%), العايلة (6%), and السيدة (5%).

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

طارتها | 18 | 18% |

مرت راجلها | 31 | 31% |

لمر التانية | 51 | 51% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 9. Frequencies and Percentages of Step Wife Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

Table 9 discloses the following. Half of the respondents: 51 tended to use the term لمر التانية, 31 referred to the step wife as طارتها, and only 18 employ مرت راجلها.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

ما تضنيش | 33 | 33% |

ما رزقهاش ربي | 11 | 11% |

مانابش عليها ربي | 19 | 19% |

ماعطاهاش ربي | 7 | 7% |

ماتجيبش دراري | 30 | 30% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 10. Frequencies and Percentages of Barren Woman Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

Table 10 shows that the euphemisms used to refer to a barren woman in the Algerian context could be classified according to the frequency of their employment from the most frequently used to the less frequently used as follows: ما تضنيش : 33 , ماتجيبش دراري : 30, مانابش عليها ربي : 19, ما رزقهاش ربي : 11, and ماعطاهاش ربي : 7.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

عجوزتي | 28 | 28% |

خالتي | 11 | 11% |

عمتي | 8 | 8% |

حماتي | 30 | 30% |

لالة | 23 | 23% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 11. Frequencies and Percentages of Mother-in-Law Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

With regard to mother-in-law euphemisms, table 11 shows that حماتي ranked at the top of the list: 30 %. In the second position was عجوزتي : 28%. Following these was لالة : 23%. At the other end of the spectrum were خالتي : 11% and عمتي : 8%.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

مرت بابا | 73 | 73% |

خالتي | 17 | 17% |

عمتي | 10 | 10% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 12. Frequencies and Percentages of Step-mother Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

In statistical terms, table 12 manifests that more than half of the respondents (73) preferred using the euphemism مرت بابا when referring to their step-mothers. However, the use of خالتي and عمتي was restricted to the frequencies of 17 and 10 respectively.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

ماعندوش | 49 | 49% |

على قد حاله | 13 | 13% |

زاوالي | 21 | 21% |

القليل | 5 | 5% |

يوم كاين وعشرة لالا | 3 | 3% |

محتاج | 6 | 6% |

ياحليل | 3 | 3% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 13. Frequencies and Percentages of Poor Person Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

Table 13 shows that almost half of the informants: 49% referred to a poor person with the euphemism ماعندوش. On the other hand, 21% used زاوالي, 13% used على قد حاله, 6% used محتاج, 5% used القليل, and only a percentage of 3% was reported for both يوم كاين وعشرة لالا and ياحليل.

4.2. The Analysis of Jordanian Arabic Data

4.2.1. Jordanian Arabic Euphemisms for Death, Sickness, and Cancer

The following four tables manifest the frequencies and percentages of the euphemisms which Jordanians use to refer to the following topics: death, sickness, and cancer respectively. Consider tables 14, 15, and 16:

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

انتقل إلى رحمة الله | 23 | 23% |

الله أخذ أمانته | 11 | 11% |

أعطاك عمره | 1 | 1% |

الله أخذ وداعته | 7 | 7% |

انتقل إلى جوار ربه | 5 | 5% |

البقاء لله | 31 | 31% |

الله استخاره | 2 | 2% |

العمر إلك | 20 | 20% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 14. Frequencies and Percentages of Death Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Under the banner of table 14, it is plainly shown that the euphemism البقاء لله ranked first with a percentage of no less than 31%. The other percentages according to the ranking of euphemisms in the above table were: 23%., 11%, 1%, 7%, 5%, 2%, and 20%.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

عيان | 18 | 18% |

متوعك | 5 | 5% |

مش مبسوط | 14 | 14% |

بعافية | 7 | 7% |

عليل | 5 | 5% |

تعبان | 20 | 20% |

مرضان | 31 | 31% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 15. Frequencies and Percentages of Sickness Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

The findings in Table (15) show that the term مرضان had the highest frequency of 31. Next, the euphemized expression تعبان had a frequency of 20 .The third frequency was recorded for the euphemism عيان with a value of 18. The euphemism عليل had the lowest frequency of 5 among the Jordanian Arabic speakers.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

هداك المرض | 31 | 31% |

المرض العاطل | 12 | 12% |

مرض عضال | 14 | 14% |

طالعتله غدة | 4 | 4% |

المرض اللي يكفيكم شره | 22 | 22% |

اللي ما يتسمى | 17 | 17% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 16. Frequencies and Percentages of Cancer Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Table (16) shows that the term هداك المرض had the highest frequency of 31among Jordanian Arabic speakers. The euphemism المرض اللي يكفيكم شرهhad the second position with a frequency of 22.The third euphemism اللي ما يتسمى had the frequency of 17, whereas the euphemisms مرض عضال, المرض العاطل, and طالعتله غدة had the lowest frequencies.

4.2.2. Jordanian Arabic Euphemisms for Jobs, Places, and Terms of Address

Question two set light on the euphemisms that were used to refer to some concepts such as certain places, jobs, and ways of naming and addressing in Jordanian Arabic. Tables from 17 through 26 show the results of each concept and the distribution of their frequencies and percentages according to the choice of the respondents.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

المدفن | 34 | 34% |

الصحراء | 18 | 18% |

التربة | 21 | 21% |

المجنة | 9 | 9% |

الجبانة | 13 | 13% |

الفستقية | 5 | 5% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 17. Frequencies and Percentages of Cemetery Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Table 17 shows that المدفن was the term that was opted for by a considerable percentage of the informants: 34% while the term الفستقية was chosen by only 5% of them. Accordingly, it is the least used term in the provided list.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

الإصلاحية | 27 | 27% |

دار الاصلاح | 14 | 14% |

مركز التأهيل و الاصلاح الاجتماعي | 22 | 22% |

دار خالته | 37 | 37% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 18. Frequencies and Percentages of Prison Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Responses in Table (18) show that the term دار خالته had the highest frequency of 37. The euphemism الإصلاحية had the second position with a frequency of 27. The euphemism مركز التأهيل و الاصلاح had the third position with a frequency of 22, whereas the euphemism دار الاصلاح had the lowest frequency of all euphemisms and terms referring to prison.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

بيت العزا | 22 | 22% |

بيت الأجر | 31 | 31% |

المدالة | 18 | 18% |

بيت المجبرين | 15 | 15% |

المأتم | 12 | 12% |

المدانة | 2 | 2% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 19. Frequencies and Percentages of the Place of Memorial Ceremony Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Table 19 indicates that the place of memorial ceremony was best represented in Jordanian Arabic by the euphemism بيت العزا with a percentage of 22%, whereas المدانة proved to be the least used euphemism in the available list.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

عامل الوطن | 10 | 10% |

عامل النظافة | 54 | 54% |

عامل الأمانة | 21 | 21% |

عامل البلدية | 15 | 15% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 20. Frequencies and Percentages of Garbage man Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

According to table 20, عامل النظافة ranked first : 54%, followed by عامل الأمانة 21% , عامل البلدية : 15% and عامل الوطن :15%.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

مره | 24 | 24% |

حرمة | 18 | 18% |

ولية | 10 | 10% |

عاقبة | 1 | 1% |

الجماعة | 3 | 3% |

الأهل | 13 | 13% |

أم الأولاد | 14 | 14% |

العيلة | 17 | 17% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 21. Frequencies and Percentages of Woman Naming Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Table 21 shows that the terms مره, حرمة, and العيلة were used more than their counterparts.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

شريكتها | 20 | 20% |

رفيقتها | 11 | 11% |

الخوية | 18 | 18% |

أختها | 51 | 51% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 22. Frequencies and Percentages of Step Wife Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

It is noticed in Table (22) that the euphemism أختها had the highest frequency of use: 51. The second position was occupied by the euphemism شريكتها with a frequency of 20.The euphemism الخويةhad the third frequency of 18. The euphemism رفيقتها had the lowest frequency of 18.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

ما بتجيب أولاد | 52 | 52% |

الله ما أعطاها | 33 | 33% |

عاقر | 10 | 10% |

عقيمة | 5 | 5% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 23. Frequencies and Percentages of Barren Woman Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Table 23 shows that the euphemisms used by Jordanians to refer to a barren woman could be ranked according to the frequency of their employment in the following order ما بتجيب أولاد:52, الله ما أعطاها: 33, عاقر : 10, and عقيمة: 5.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

عمتي | 40 | 40% |

خالتي | 12 | 12% |

مرت عمي | 32 | 32% |

خالتو | 16 | 16% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 24. Frequencies and Percentages of Mother-in-Law Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Table (24) shows that the euphemism عمتي had the highest frequency: 40. Next came the euphemism مرت عمي with a percentage of 32%. The euphemism خالتو occupied the third position: 16%. Last but not least, the euphemism خالتي was represented by a frequency of 12.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

مرت الأب | 72 | 72% |

الخالة | 28 | 28% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 25. Frequencies and Percentages of Step-mother Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

From table 25, it could be stated that the users of the euphemistic expression مرت الأب outnumbered those of the term الخالة, with the values 72 and 28 respectively.

Euphemism | Frequency | Percentage |

على باب الله | 29 | 29% |

على قد حاله | 22 | 22% |

مستور | 17 | 17% |

رزقه قليل | 8 | 8% |

دخله محدود | 10 | 10% |

جماعة بسطا | 14 | 14% |

Total | 100 | 100% |

Table 26. Frequencies and Percentages of Poor Person Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

Results in Table (26) show that the euphemism على باب الله was reported to be the most frequently used among Jordanians: 29%. One rank below it was على قد حاله : 22%. The term مستور occupied the third position with a frequency of 17%. Below it in rank were the euphemisms جماعة بسطا, دخله محدود, and رزقه قليل with their percentages following the same order: 14%, 10%, and 8%.

4.3. ContrastingAlgerian and Jordanian Spoken Arabic Data

- Similarities between Algerian and Jordanian Euphemisms

The analysis of the data that the researchers had at their disposal revealed the following similarities between the euphemisms pertaining to Algerian and Jordanian Arabic:

- Both Algerian and Jordanian native speakers regard certain topics and concepts like death, sickness, cancer, certain places, jobs, and ways of naming and address as taboos. Thus, they handle them with care by dint of making recourse to the use of euphemistic expressions.

- Algerian and Jordanian Arabic speakers prefer to be polite and indirect, that's why they both try to avoid threatening the face of those they address by means of various "euphemisms"

- There is a tendency on the part of both Algerians and Jordanians to use the same two euphemisms viz: أعطاك عمره and البقاء لله to refer to the topic of death.

- In a similar vein, Algerians and Jordanians have been attested to have one common denominator: the use of عيان to refer to sickness, and هداك المرض, اللي ما يتسمى to refer to cancer, though with differing degrees.

- As far as euphemisms of some places are concerned, both Jordanian and Algerian spoken Arabic have at their disposal the following: الجبانة and المدفن to refer to the cemetery, and بيت العزا to name the place of memorial ceremony.

- In a similar vein, عامل النظافة is used in both societies to refer euphemistically to the garbage man.

- Woman naming euphemisms have also revealed similarities in: أم الأولاد, مره, العيلة.

- Both Algerians and Jordanians use ما بتجيب أولاد, الله ما أعطاها to refer to a barren woman, عمتي and خالتي to address a mother-in-law ,and على قد حاله to soften the impact of referring to a poor person.

4.3.2 Differences between Algerian and Jordanian Euphemisms

Despite the aforementioned similarities between Algerian and Jordanian Spoken Arabic in using euphemisms, it should be noted that some differences between them were attested.

- Though some euphemistic expressions are shared between the two dialects under scrutiny, they tend to be pronounced in different ways due to the differences in their phonemic inventories.

- Moreover, in some cases, one of the two varieties of Arabic tends to outnumber the other one in terms of the euphemisms it supplies to refer to certain taboos. For instance, Jordanians use more euphemisms than Algerians when "the cemetery" is brought to the fore.

- In addition, there are instances in which Jordanians are more indirect and polite in the euphemisms they use like in the case of "step wife". On the other hand, there are situations in which Algerians are less direct, as in the case of a barren women.

Conclusion

Immersion in the present research work for a considerable amount of time has disclosed that despite the existence of similarities between Algerian and Jordanian euphemisms when referring to the taboo topics and concepts of death, sickness, cancer, certain places, jobs, and terms of address, they tend to differ in many respects. Axiomatically, such differences could be attributed to the fact that "euphemism" is not only a linguistic phenomenon, but a cultural one as well. Hopefully, this study, which can capture neither the breadth nor the depth of this linguistic and cultural phenomenon, will pave the road for subsequent studies about a highly important topic like the one in hand. Therefore, as a compensation for some of the deficiencies and limitations of the present research work, it is strongly recommended that its frontiers could be pushed back by virtue of conducting it with a larger sample. To this end, the questionnaires are to be administered to a higher number of Algerian and Jordanian respondents. In doing so, the researcher may say with confidence that the sample is representative of the whole population. It is also recommended to inquire into more areas where the use of euphemisms in both societies is required by taking into account the extent to which age and gender might affect the choice of euphemistic expressions both in the Algerian and Jordanian society.

APPENDICES

Appendix I: Questionnaire of Euphemisms in Algerian Arabic

الأخ الفاضل ...، الأخت الفاضلة....،

السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته ،،،،

يسرني أن أضع بين أيديكم هذا الاستبيان الذي صمم لجمع المعلومات اللازمة لدراسة حول ظاهرة تلطيف العبارات و الكلمات باللغة العربية. نأمل منكم التكرم بالإجابة على الأسئلة بدقة ، حيث أن صحة النتائج تعتمد بدرجة كبيرة على صحة إجابتكم ، لذلك نهيب بكم أن تولوا هذا الاستبيان اهتمامكم ، فمشاركتكم ضرورية ورأيكم عامل أساسي من عوامل نجاحها. ونحيطكم علما أن جميع إجاباتكم لن تستخدم إلا لأغراض البحث العلمي فقط .

شاكرين لكم حسن تعاونكم

وتفضلوا بقبول فائق التقدير والاحترام

من إعداد : |

سامية عزيب |

القسم الأول: البيانات الشخصية

الجنس: ذكر أنثى

العمر: اقل من 30 من 30 إلى اقل من 40

من 40 إلى اقل من 50 من 50 سنة فأكثر

الحالة الاجتماعية:

أعزب متزوج

المؤهل العلمي:

ابتدائي إعدادي ثانوي

جامعي ماجستير دكتوراه

القسم الثاني:

يرجى تحديد العبارة/ العبارات اللطيفة التي تلجا إليها عند التحدث أو الإشارة الى الأمور غير المرغوب فيها و المبينة أدناه، وذلك بوضع إشارة x في الخانة المناسبة.

أولا: الموت

مات |

|

حاجة الله الداه الله |

|

عطاك عمر |

|

الدايم ربي |

|

البقاء لله |

|

رحمة الله عليه |

|

حكم عليه ربي |

|

ثانيا: المرض

ماقادرش |

|

مريض |

|

عيان |

|

تعبان شوي |

|

معلول |

|

غلبان |

|

كما حب ربي |

|

في حالة |

|

فلفراش |

|

ثالثا: السرطان

القونصير |

|

المرض ليمامليحش |

|

المرض الخامج |

|

هداك المرض |

|

المرض ليمايتسماش |

|

هداك المرض عافانا الله |

|

القسم الثالث: المفاهيم غير المرغوب فيها

أولا: الأماكن

- المقبرة

المقبرة |

|

المدفن |

|

الجبانة |

|

ب- السجن

السجن |

|

الحبس |

|

السيلون |

|

مركز الاصلاح الاجتماعي |

|

|

|

ج- مكان العزاء

بيت لعزا |

|

دار لعزا |

|

نروح عند موالين الميت |

|

ثانيا: بعض الوظائف

ا- الزبال

البوباليسث |

|

عامل النظافة |

|

ليكاينظف |

|

ثالثا: العبارات التي تستخدم لتسمية وتعريف بعض أفراد المجتمع

ا-المرأة

لمره |

|

المادام |

|

المخلوقة |

|

العايلة |

|

أم لولاد |

|

السيدة |

|

ب-الضرة

طارتها |

|

مرت راجلها |

|

لمر التانية |

|

ج- المرأة العاقر

ما تضنيش |

|

ما رزقهاش ربي |

|

مانابش عليها ربي |

|

ماعطاهاش ربي |

|

ماتجيبش دراري |

|

- الحماة

عجوزتي |

|

خالتي |

|

عمتي |

|

حماتي |

|

لالة |

|

ه- زوجة الأب

مرت بابا |

|

خالتي |

|

عمتي |

|

و- الفقير

ماعندوش |

|

على قد حاله |

|

زاوالي |

|

القليل |

|

يوم كاين وعشرة لالا |

|

محتاج |

|

ياحليل |

|

Appendix II: Questionnaire of Euphemisms in Jordanian Arabic

الأخ الفاضل ...، الأخت الفاضلة....،

السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته ،،،،

يسرني أن أضع بين أيديكم هذا الاستبيان الذي صمم لجمع المعلومات اللازمة لدراسة حول ظاهرة تلطيف العبارات و الكلمات باللغة العربية. نأمل منكم التكرم بالإجابة على الأسئلة بدقة ، حيث أن صحة النتائج تعتمد بدرجة كبيرة على صحة إجابتكم ، لذلك نهيب بكم أن تولوا هذا الاستبيان اهتمامكم ، فمشاركتكم ضرورية ورأيكم عامل أساسي من عوامل نجاحها. ونحيطكم علما أن جميع إجاباتكم لن تستخدم إلا لأغراض البحث العلمي فقط .

شاكرين لكم حسن تعاونكم

وتفضلوا بقبول فائق التقدير والاحترام

|

|

من إعداد:

الأستاذ الدكتور محمود القضاة

القسم الأول: البيانات الشخصية

الجنس: ذكر أنثى

العمر: اقل من 30 من 30 إلى اقل من 40

من 40 إلى اقل من 50 من 50 سنة فأكثر

الحالة الاجتماعية:

أعزب متزوج

المؤهل العلمي:

ابتدائي إعدادي ثانوي

جامعي ماجستير دكتوراه

القسم الثاني:

يرجى تحديد العبارة/ العبارات اللطيفة التي تلجا إليها عند التحدث أو الإشارة الى الأمور غير المرغوب فيها و المبينة أدناه، وذلك بوضع إشارة x في الخانة المناسبة.

أولا: الموت

انتقل الى رحمة الله |

|

الله أخذ أمانته |

|

أعطاك عمره |

|

الله أخذ وداعته |

|

انتقل الى جوار ربه |

|

البقاء لله |

|

الله استخاره |

|

العمر الك |

|

ثانيا: المرض

عيان |

|

متوعك |

|

مش مبسوط |

|

بعافية |

|

عليل |

|

تعبان |

|

مرضان |

|

ثالثا: السرطان

هداك المرض |

|

المرض العاطل |

|

مرض عضال |

|

طالعتله غدة |

|

المرض اللي يكفيكم شره |

|

اللي ما يتسمى |

|

القسم الثالث: المفاهيم غير المرغوب فيها

أولا: الأماكن

- المقبرة

المدفن |

|

الصحرا |

|

التربة |

|

المجنة |

|

الجبانة |

|

الفستقية |

|

ج- السجن

الإصلاحية |

|

دار الاصلاح |

|

مركز التأهيل و الاصلاح الاجتماعي |

|

|

|

د- مكان العزاء

بيت العزا |

|

بيت الأجر |

|

المدالة |

|

بيت المجبرين |

|

|

|

المدانة |

|

اللازمة |

|

ثانيا: بعض الوظائف

ا- الزبال

عامل الوطن |

|

عامل النظافة |

|

عامل الأمانة |

|

عامل البلدية |

|

ثالثا: العبارات التي تستخدم لتسمية وتعريف بعض افراد المجتمع

ا-المرأة

مره |

|

حرمة |

|

ولية |

|

عاقبة |

|

الجماعة |

|

الأهل |

|

أم الأولاد |

|

العيلة |

|

ب-الضرة

شريكتها |

|

رفيقتها |

|

الخوية |

|

أختها |

|

ج- المرأة العاقر

ما بتجيب أولاد |

|

الله ما أعطاها |

|

عاقر |

|

عقيمة |

|

- الحماة

عمتي |

|

خالتي |

|

مرت عمي |

|

خالتو |

|

ه- زوجة الأب

مرت الأب |

|

الخالة |

|

و- الفقير

على باب الله |

|

على قد حاله |

|

مستور |

|

رزقه قليل |

|

دخله محدود |

|

جماعة بسطا |

|

Reference lists